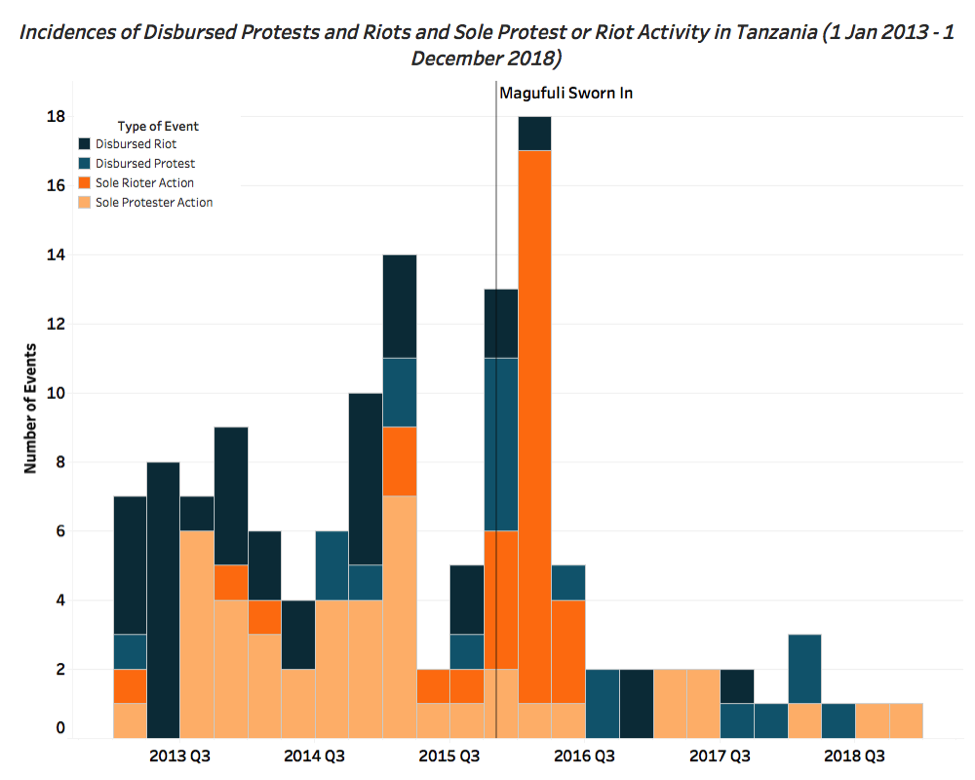

Tanzanian President John Magufuli was sworn into office in November 2015 after campaigning on promises to crack down on corruption and to bolster employment in the country (The Citizen, 21 November 2015). Though Magufuli’s reform efforts were initially met with public applause (most notably through the #WhatWouldMagufuliDo), his policy agenda has taken a more controversial and autocratic turn (Into Africa, 28 November 2018). Following a surge in politically motivated riot activity in 2016, Magufuli banned public protests and incidences of riots and protests have sharply declined since. The suppression of public demonstrations is just one of the ways in which Tanzania’s civic space has shrunk dramatically since Magufuli took office.

Magufuli has dramatically limited civic space and freedom of expression in Tanzania in response to political competition. Relatedly, violence against civilian political targets is increasingly conducted by unidentified armed groups (UAGs).

Magufuli, as the Chamba Cha Mapinduzi’s (CCM) candidate in the 2015 elections, won more than 58% of the votes. This was most competitive presidential election in Tanzania’s history, and marked the first time that the CCM presidential candidate won less than 60% of the popular vote since the CCM removing the ban on political opposition parties in 1992 (Psephos). The CCM’s bid to maintain its position as the dominant party in Tanzania has taken a toll on the country’s reputation for stability and the vibrancy of its civil society.

Decline in Protest, Brief Surge in Riots

Protest activity has undergone a marked shift since Magufuli took office. Protests and rioting activity have fallen dramatically since an uptick in mid-2016. In 2016 in total there were 27 incidences of riots and protests, which fell to 8 such events in 2017 and 7 thus far in 2018.

One of the most marked declines is in protests. There have been just 9 protests in 12 quarters since November 11, 2015. In the 12 quarters prior to Magufuli’s swearing in, there were 35 protests. This decline is in part because of a ban on “all opposition protests,” implemented in August 2016 following a confrontation between Tanzanian police and protesters (Africa News, 6 August 2016).

Another notable pattern is the brief surge in rioting early in Magufuli’s tenure. The first quarter of 2016 saw a surge in sole rioter action, rising from 4 events in the previous quarter to 16 events. Many of these events served political ends and were associated with runoff elections. In 8 of the 16 events, offices belonging to the Civic United Front (CUF) were burned down; in another 4 events, houses and meeting places associated with the CCM were burned down.

Increase in Violence Against Civilians by Unidentified Armed Groups

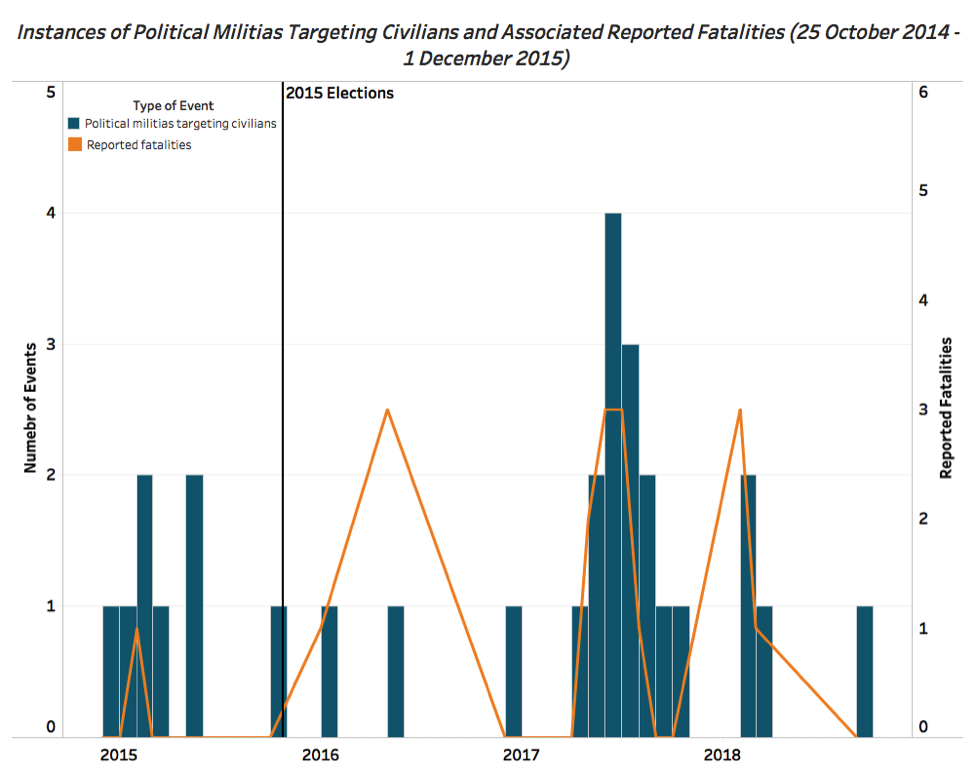

In addition to politically motivated riot activities, there has also been a surge in unidentified militias targeting civilians since Magufuli took office. All 14 of the events in which political militias targeted civilians during the surge in such activity between April and October 2017 were perpetrated by UAGs. The 14 attacks across the two quarters resulted in 9 reported fatalities. As demonstrated below, instances of political militias targeting civilians in mid-2017 surpassed the number of such events and associated fatalities in the year leading up to the 2015 elections.

Political Context

Taken together, the decline in peaceful protests and dual surges in politically motivated riots and civilian targeting by UAGs under Magufuli suggest that Tanzanian politics is headed down a dangerous path. These patterns have emerged at a time in which the government has adopted new, stricter regulations on the freedom of speech and expression in the country.

The Electronic and Postal Communications (Online Content) Regulations passed under Magufuli, for example, “gives the government the right to revoke a permit if a site publishes content that ‘causes annoyance’ or ‘leads to public disorder’” (DW, 17 April 2018). In his three years in office, Magufuli has overseen the arrest of a number of government critics (Article 19, 29 March 2017) , the shuttering of a number of media outlets, and the banning of opposition party protests (Mail and Guardian, 2 July 2018).

The government’s crackdown on opposition parties and critics of the government has contributed to this turn, by limiting the ability for political opposition to express itself non-violently. Denied the opportunity to legally and peacefully voice their grievances and make their case to the Tanzanian public, critics are seeking to affect change through extra-institutional and often violent means (Przeworski 1999). CCM-backed violence by rioters and political militias only makes the need for opponents to resort to violence more acute. Magufuli’s attempt to reclaim the political hegemony of the CCM has made the political atmosphere in Tanzania less stable and more violent.