Demonstrators took to the streets ahead of the December 20th legislative elections. They are calling for constitutional limits on presidential and legislative terms, a revival of the National Independent Electoral Commission, and other political reforms (Africa News, 6 December 2018). The resurgence of public demonstrations in Togo adds yet another iteration of the cycle of demonstration and repression that has been a feature since Faure Gnassingbé became president in 2005.

Though many of the demands that the protesters are levying have remained the same over this period — and some even pre-date Faure’s tenure, public demonstrations are increasingly being dispersed by the police. Relatedly, in recent years, opponents of the regime and demonstrators are engaging in more riot activity. The Gnassingbé Regime’s response has included banning protests, shutting down the internet, and violently dispersing demonstrations (Africa News, 6 December 2018; Quartz Africa, 7 September 2017; Reuters, 18 October 2017). At least two people were killed by security forces as they dispersed protests in early December 2018. The regime’s handling of demonstrations has only made the need for serious political reforms more evident. If some changes are not soon evident, the cycle of demonstrations in Togo will continue, and will likely be characterized by increasingly violent interactions between demonstrators and the security sector.

Background to the Cycles of Protest

Incumbent President Faure Gnassingbé took power in 2005, after the passing of his father. This was described by the African Union as a “military coup” (BBC, 7 February 2005). Faure’s ascension involved a number of illiberal reforms, including the circumventing of a provision in Togo’s constitution which stipulated that the leader of the national assembly is the next in line after the death of a President. In preventing the speaker of the national assembly from entering the country, and repealing a provision that called for elections within 60 days of a leader passing (BBC, 7 February 2005), Faure and co-conspirators engaged in a palace coup.

Though officially banned, a number of public demonstrations against Gnassingbé occurred soon after he took power and the 2005 presidential elections (The Guardian, 20 February 2005). There were more than 80 reported fatalities in 2005 associated with public demonstrations – the vast majority of which were associated with 12 dispersed riots that took place that year. Once the 2005 post-election violence tapered off, there were very few public demonstrations in Togo until the 2010 election year. Since that time, Togo has experienced several cycles of political unrest (see below). Elections remain a catalyst for demonstrations demanding political reform.

Protesters and rioters come from a variety of backgrounds, including labor unions, student groups and the opposition. Though the protesters have not produced the political reforms that they seek, the events have left an indelible mark on the country’s conduct of politics. The protest wave in 2012-2013 was organized by “a coalition of opposition and civil society groups known as Let’s Save Togo, which has been pushing for sweeping electoral reforms” (Al Jazeera, 25 July 2013). This movement forced the government to delay legislative elections (held in 2013) that were originally scheduled to take place in October 2012. In 2017, a reform coalition engaged in demonstrations demanding political reform that once again resulted in an election delay. Legislative elections, originally scheduled for July 2018 have been delayed until December 20, 2018.

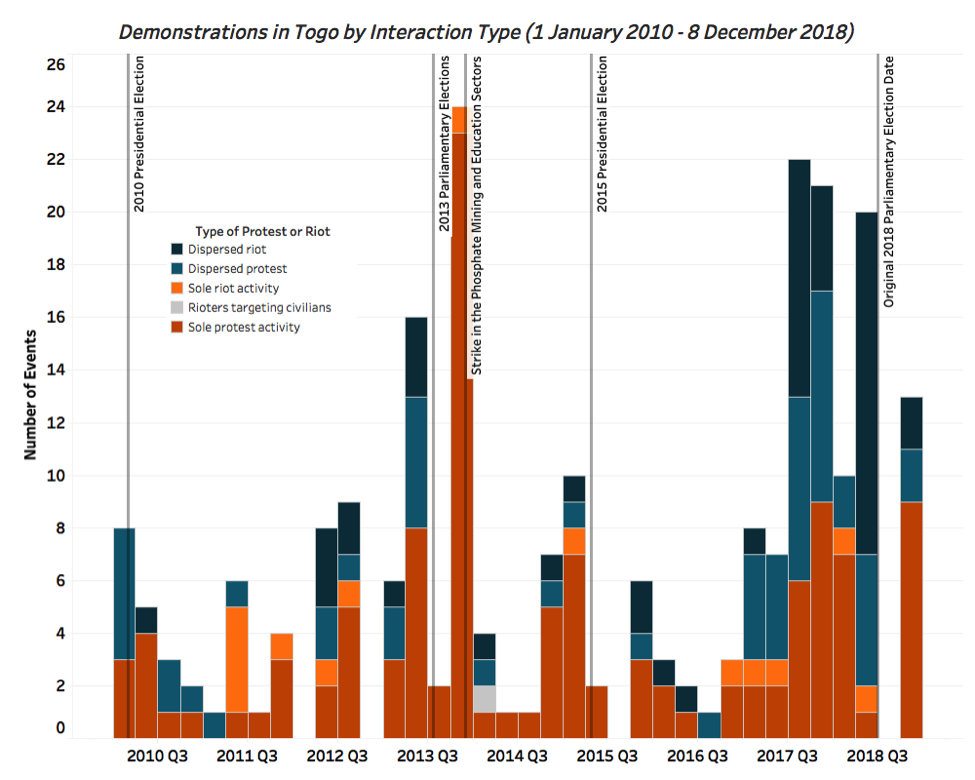

Despite high and sustained levels of protest in 2017 and 2018, protest levels have not surpassed the peak of the fourth quarter of 2013. During that three month span, there were 24 public demonstrations, 23 of which were protests and one of which was a riot.

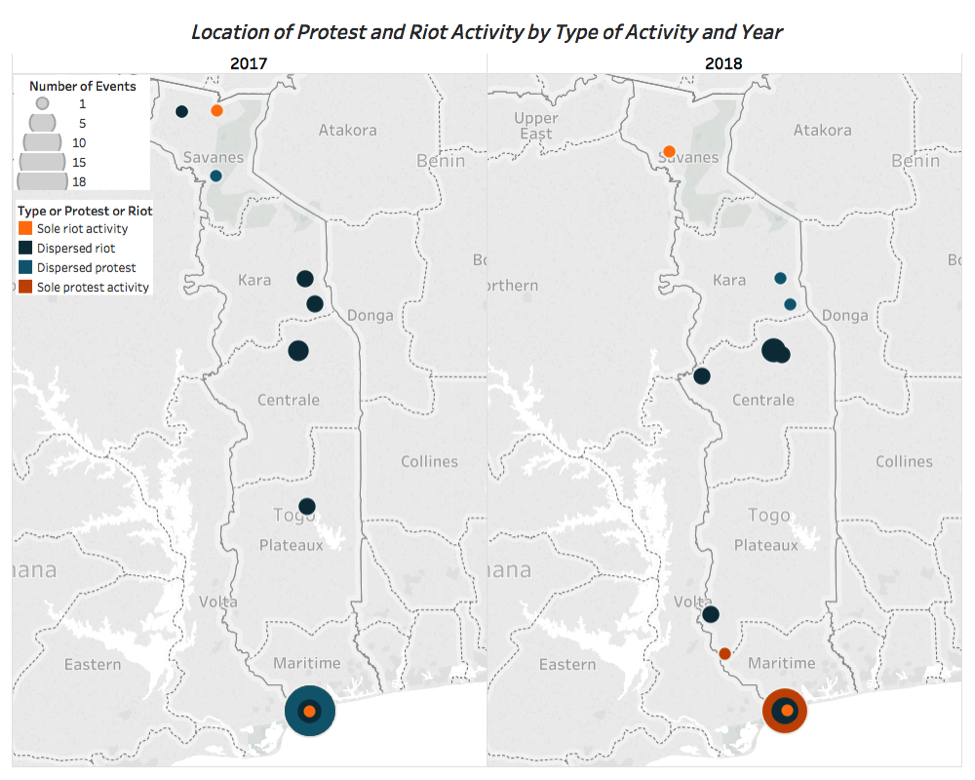

As demonstrated below, the geography of the demonstrations has also shifted. Though the majority of the demonstrations in 2018 (51%) were in the capital, Lome, this is a decline from 65% in 2017. Demonstrations took place across 10 different locations in 2018, thus far, as compared to 8 locations in the entirety of 2017. The protest activity in 2018 outside of Lome was still primarily focused on airing political grievances.

What’s Changed in Demonstrations and Why?

As the graph above demonstrates, public demonstrations over time have shifted towards riot activity and confrontations with the state. In 2018 to date, 37% of the public demonstrations have been riots dispersed by the security sector. This is a 5% increase from the proportion of public demonstrations in 2017 that involved such a confrontation and it is the highest proportion recorded between 2010 and 2018.

The shift towards riot activity and dispersed protests speaks to the heightened tensions in the country and dwindling prospects for a peaceful resolution of the political crisis. The Gnassingbé regime appears to be boxing out the political opposition. Ahead of the December 20th legislative elections, Togo’s Constitutional Court has not yet validated the ballots for any of the 14 opposition parties that have participated in the demonstrations this year (News24, 11 November 2017) .

The increase in the proportion of public demonstrations that are ‘dispersed riots’ is associated with a decline in free protest. In 2010, free protests accounted for 53% of demonstrations. By 2018, that proportion had fallen to 37%.

The second quarter of 2018 recorded the most riot-related activity since 2010; over this three month span, there were 14 riots total, 13 of which were dispersed by the security sector. Though these confrontations have not resulted in a surge in the number of reported fatalities, the specter of the deadly clashes between demonstrators and the security sector in 2005 looms large.

Conclusions: Elections and Reform

Protests in Togo will continue if no credible commitment to major political reform emerges from government. The escalation in confrontations between demonstrators and the Togolese security sector in recent years suggest that the December 20 legislative elections could spur further, and more violent, unrest. The political opposition has called for a boycott of the elections, describing them as “fraudulent” and calling for sustained protests (News24, 11 November 2018). The government’s efforts to deny the political opposition legal and institutional avenues to vent their grievances will not mitigate their efforts, or cause protesters to dissipate. In keeping with previous elections, demands by protesters and political opposition that #FaureMustGo could prompt Gnassingbé to violently shut down protests to preserve his access to power.