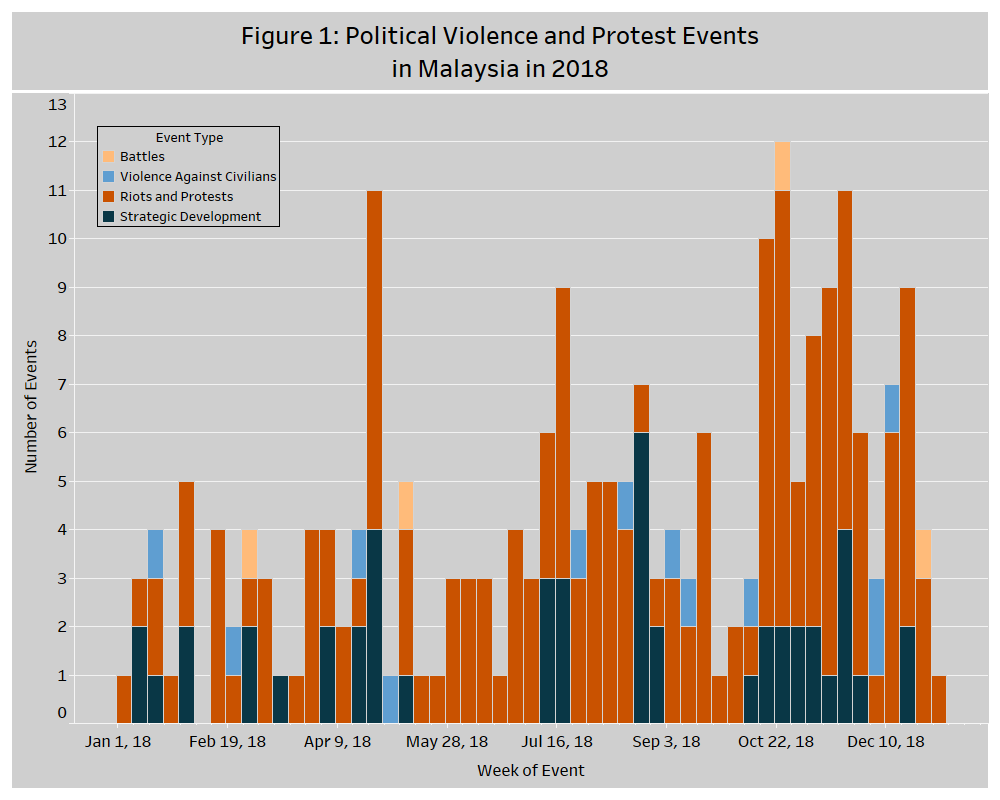

Drawing from a number of publicly available sources, ACLED Malaysia data include 227 events concerning political violence, riots, protests and other strategic developments in 2018. Protests make up the majority of recorded events (see Figure 1). After the historic general elections in 2018, in which the opposition defeated the ruling coalition which had run the country since 1957, many held that a “new Malaysia” was emerging. However, towards the end of the year, as demonstrations against the potential signing of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination increased, there appeared to be a resurgence in Malay-Muslim identity politics, threatening the idea of a “new Malaysia.”

GE14 and Malaysia Baharu

In the lead up to the general elections in May 2018, many believed the Barisan Nasional (BN) coalition, which includes the dominant United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), would remain in power, having ruled the country since 1957. Prior to the elections, the People’s Justice Party (PKR) and Malaysian United Indigenous Party (BERSATU), a new party formed by former Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad, formed the coalition Pakatan Harapan (PH). Despite having served as Prime Minister from 1981-2003 as leader of the UMNO, and despite demonstrations by those who rejected his selection, Mahathir Mohamad was chosen to lead the PH with the understanding that he would eventually pass power on to Anwar Ibrahim, the leader of the PKR (Nikkei Asian Review, 27 December 2018). Prime Minister Najib Razak’s involvement in the misappropriation of money from 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB), a state investment fund, was seized on by the PH during the campaign as a reason for the lack of economic progress in the country, which turned many away from the ruling coalition (Washington Post, 3 July 2018). The unexpected victory of the PH led many to hope for a Malaysia Baharu, or “new Malaysia.”

After PH’s electoral victory, many UMNO members resigned from the party, seeking to join the victorious PH (Channel News Asia, 21 December 2018). This has been met with reservation by many PH supporters; in particular, many are wary of the continuation of Bumiputera affirmative action policies which favor the Malay-Muslim population for academic and economic opportunities over other ethnic groups in the country (New Mandala, 16 September 2018). Resistance to moving away from Bumiputera policies that favor Malay-Muslims was apparent in the debate over whether to sign the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD), which Mahathir had previously indicated he would sign. After a number of protests against the signing of the ICERD, led by UMNO and the Malaysian Islamic Party (PAS), the decision was taken not to sign the ICERD, which led to a large celebratory rally on 8 December (The ASEAN Post, 20 December 2018).

Growing appeals to racial and religious identities could also be seen in November in the riots that broke out at the Seafield Sri Maha Mariamman Hindu temple in Selangor, leading to the death of an ethnic Malay fireman. While some have noted the riots were a result of a disagreement over whether the temple should be moved, others have pointed to an increase in rhetoric calling for the demolition of Hindu temples in the lead up to the temple riots (Asia Times, 6 December 2018). In December, a number of demonstrations were held by Muslim groups calling for justice for the fireman who was killed.

The hopes for a new Malaysia were further dampened, as seen at the 100-day mark of the new PH government, when protests were organized by those dissatisfied that the promises the coalition ran on have not yet been fulfilled. University students have also protested over the failure of the PH government to uphold its commitment to easing the burden of repaying student loans provided through the National Higher Education Fund Corporation (PTPTN).

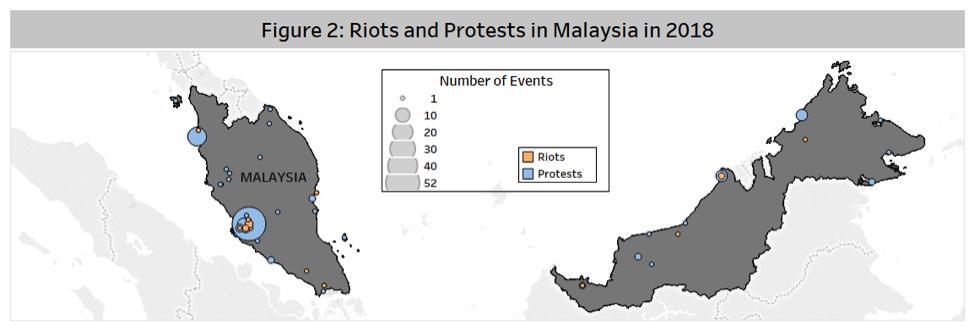

In addition to the above noted protests, throughout 2018, many demonstrations have taken place across the country concerning various issues (see Figure 2). As the second largest producer of palm oil in the world, Malaysia has experienced protests around the decision of the European Union not to import palm oil due to environmental concerns (The Independent, 5 December 2018).

Indigenous land access has also been a driver of demonstrations in Malaysia. A number of demonstrations were held by members of the Orang Asli indigenous group in opposition to various development initiatives that would harm their ancestral lands (Amnesty International, 29 November 2018). Other indigenous groups, including the Dayak and Penan, also joined with the Orang Asli to protest the passage of the Sarawak Land Code Amendment in the Sarawak State Assembly in July. The amendment interferes with the rights of indigenous people to control communal lands.

Armed Clashes

Aside from protests, Malaysia continues to contend with regional security threats in Sabah, part of the island of Borneo. The region has been on alert since February 2013 when 200 members of an armed group loyal to the Sultanate of Sulu landed in Lahad Datu, leading to a five-week standoff in which 78 people were reportedly killed (Free Malaysia Today, 13 March 2018). The Eastern Sabah Security Zone was established in March 2013 as a direct result, and the Eastern Sabah Security Command (Esscom) was formed in April 2013 to ensure protection of the region.

Given its location near the Philippines and Indonesia, both of which are contending with Islamic militant groups (e.g. Abu Sayyaf in the Philippines and Jemaah Islamiyah in Indonesia), there have been concerns that militants will use Sabah as a refuge and a base from which to recruit (Geopolitical Monitor, 2 January 2018). In 2018, there was an increase in the number of kidnap-for-ransom groups operating in Sabah’s coastal waters (Free Malaysia Today, 13 March 2018). However, direct engagement between Esscom and militants only occurred twice in 2018. In February, a shoot-out occurred in a palm oil plantation area near Tawau city. Three men suspected of being foreign ‘terrorists’ were reportedly shot and killed by Esscom. In May, Esscom was part of an operation that saw engagement with a Filipino kidnap-for-ransom group off the coast of Sabah, reportedly leading to the deaths of four men from the group.

Arrests

Aside from political violence and protests, ACLED has also recorded a number of strategic developments in Malaysia in 2018, notably numerous arrests of suspected militants. Malaysia’s Special Branch Counter-Terrorism Division has sought to preempt any ‘terrorist activity’ in Malaysia, using its authority under the Security Offences (Special Measures) Act (SOSMA) passed in 2012. Despite the passage of the act, one attack was successfully carried out by ISIS in June 2016 in Kuala Lumpur (CNN, 4 June 2016). In 2018, a number of individuals were arrested on charges spanning involvement, recruitment, plotting and financially supporting foreign ‘terror groups.’ Members of two militant cells based in Malaysia, Asoib and Ar Rayah, were also arrested last year (Benar News, 14 September 2018). The former was allegedly plotting an attack on Saudi Arabia, while the latter had planned attacks in Malaysia around Malacca and Penang.

Despite the presence of such activity in the country, the large number of arrests being carried out by the counter-terrorism unit with little oversight has caused some backlash from those concerned that the line is not always clear between actual threats and legitimate opposition to the government. SOSMA has been used in the past to detain prominent activists (The Malay Mail, 24 November 2016). Many families of those detained under SOSMA protested the law this past year, calling for it to be abolished (Free Malaysia Today, 24 October 2018).

Conclusion

In 2019, it remains to be seen how effective the PH government will be in carrying out its campaign promises. As well, the new government, which has ostensibly been tasked with moving the country away from Malay-Muslim identity politics, will continue to face a resistant public (New Mandala, 18 December 2018). Going forward, ACLED will continue to record events of political violence and protests as a part of its weekly real-time coding releases.