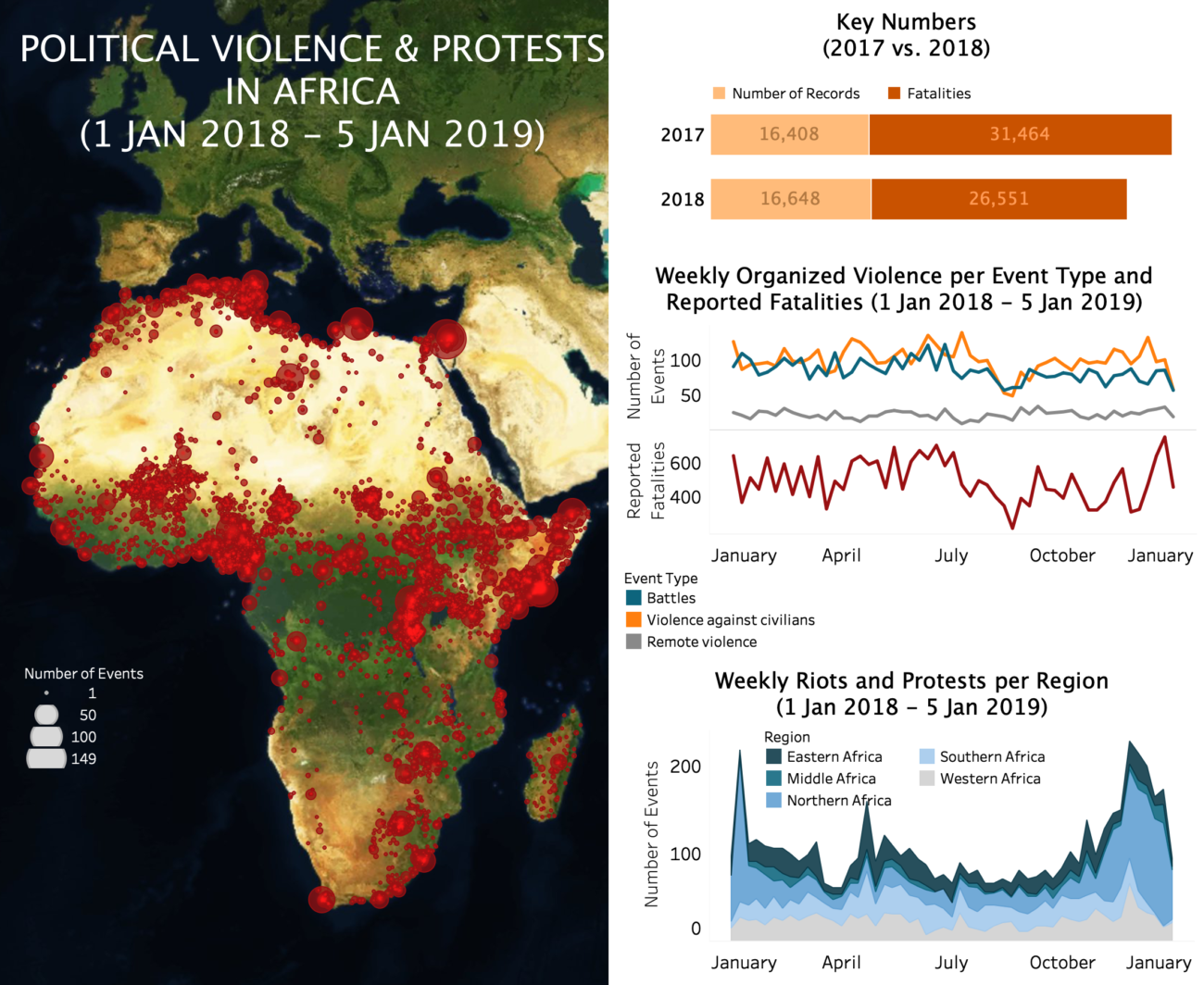

As 2018 drew to a close, political violence and protests in Africa rose. This overview focuses on a selected number of countries where some of the most important developments occurred at the end of last year and into the current period (between December 16th, 2018, January 5th, 2019).

First, the number of organized armed violent events in Egypt nearly doubled between November and December 2018 due to the continuing escalation of the fighting between Egyptian forces and the Islamic State. With these numbers, Egypt became the third most active country on the Africa continent in December 2018, right after Somalia and Nigeria. At least 38 episodes of armed clashes, IED attacks and shelling and airstrikes resulting in a reported nearly 60 fatalities were recorded between December 16th and January 5th, mostly in the Al Arish, Rafar and Sheikh Zuweiyid areas of North Sinai. Signs of escalation are also shown in the significant rise in the collaboration between Egyptian and Israeli air forces to conduct air operations against the militants.

Second, violence involving Boko Haram militants significantly rose in December 2018, with nearly twice as many reported events and fatalities compared to October 2018. There were important developments in the second half of December in Nigeria and Niger. In Niger, Boko Haram militants carried out regular attacks and pillaging of villages in the Diffa region, though suffered an important rebuff between December 28th-January 1st following combined air and ground operations launched by the Nigerien contingent of the MNJTF along the Komadougou River and islands of Lake Chad (287 militants were reported killed). In Nigeria, fighting escalated towards the end of the month as Islamic State-led fighters made significant territorial advances against Nigerian troops in Borno and Yobe states. The militants captured a naval base in Baga on December 27th and took over several nearby villages in subsequent days. They tried to capture Monguno on several occasions between December 29-30th; and they overran military bases on January 1st in Biu, Hawal Mobbar and Gujba LGAs, between Borno and Yobe. The Nigerian forces responded by bombing these areas.

Third, militant and intercommunal violence has remained sustained in Burkina Faso and Mali since December 16th. In Burkina Faso, militants of the Group for Support of Islam and Muslims (JNIM) and of the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) continued to target local government representatives in the Est and Sahel regions: they killed seven municipal councillors, customs officers and relatives and they targeted schools, abducting a director and burning down several school buildings. Two key events show the significant potential for a further escalation of the violence in Burkina Faso. First, a JNIM ambush on a gendarme convoy on December 27th in the Boucle du Mouhoun region, along the border with Mali, which left 10 gendarmes killed, reinforced the cross-border nature of the terrorist threat and the easy spillovers from Mali. Second, the violence perpetrated by Koglweogo and Mossi militias against Fulani communities in Yirgou (Centre-Nord) on January 1st and 2nd, immediately after they were attacked by Ansaroul Islam militants, showed increasing signs of a link between militancy and intercommunal violence. The attack left at 47 Fulanis dead and could further escalate ethnic tensions in this area. Meanwhile in Mali, also on January 1st, Dogon militiamen perpetrated yet another large attack on Fulani communities, in Kologon village of the Bankass area (Mopti region), reportedly killing 37 civilians.

Fourth, tensions rose in both the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Madagascar in the context of presidential elections. In the DRC, riots broke out in the lead up to the December 30th polls in Goma, Beni, and Butembo against the postponement of voting in Beni, Butembo and Yumbi due to the Ebola outbreak. Police commonly dispersed these riots with tear gas and live ammunition, leaving one demonstrator killed. Political allegiances were also suspected of precipitating large-scale violence between the Batende and Banunu ethnic groups in Yumbi (Maï-Ndombe) on December 18th, resulting in at least 120 fatalities. On voting day, violence erupted at various polling stations amidst fears of vote tampering. Voters responded to problems with voting machines by assaulting members of the Independent National Electoral Committee (CENI) or by preventing them from accessing polling stations, and by ransacking or burning polling stations. Meanwhile, armed groups– including the state forces, Mayi Mayi, Nduma Defence of Congo and the coalition of Nyatura and Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda–interfered with voting in North Kivu, Maniema, and Kasai, instructing voters which candidates to cast their ballots for. Violence will likely escalate once the results are announced, prompting fears of spillovers into neighboring countries and the pre-emptive deployment of US forces to Gabon.

In Madagascar, violence and intimidation by Dahalo bandits and other unknown gunmen hampered the voting for the second round of the presidential elections in several locations between December 18th-20th, and rose before the results were announced. As the Electoral Commission confirmed the victory of Rajoelina, supporters of his opponent Ravalomanana, took the streets of Antananarivo at least four times between December 29th– January 5th. Considering the high stakes of the elections, there are fears of a further escalation reminiscent of the 2009 coup when Rajoelina ousted Ravalomanana from power, resulting in 40 civilian deaths.

Fifth, in Cameroon, fighting between the government forces and Ambazonian separatists has continued at a lower pace in December compared to the peaks of September and October 2018, but threatens to pick up again. A key commander of the Ambazonia Defense Forces (ADF) was killed in renewed fighting in the Sud-Ouest on December 21st. Fighting also reportedly intensified again from January 1st in several areas following President Biya’s vow to neutralize the separatists in his New Year speech. Over 200 battles resulting in 844 reported fatalities have so far been recorded in the ACLED dataset since September 2017. Over half of these have occurred since September 2018.

Lastly, despite the relative reduction in the levels of political violence in South Sudan and Sudan in 2018, developments since December 16th show that both countries remain very volatile. In South Sudan, fighting between the army and rebels of the National Salvation Front (NAS) took place in and around the Yei and Lobonok areas of Central Equatoria on December 16th and 30th, amidst NAS allegations of army and paramilitary deployments in the area. These were the first battles between these two actors since end 2017, when the military sought to regain a few NAS territories, including those captured from the SPLA-IO in Kajo-Keji in Central Equatoria. The situation could quickly escalate as NAS remains outside the September ARCSS peace agreement. Accusations that soldiers detained and assaulted several international CTSAMM staff deployed to investigate ceasefire violations outside Juba on December 17th further endangered the agreement’s implementation.

Sudan was rocked by nationwide protests and riots in December. Whilst initially student-led and stirred by the soaring living costs and economic deterioration in the country, the demonstrations quickly evolved into more broad-based revolts against the regime of President Bashir. Over 100 protests and riots were reported in most major towns in the country, beginning in Blue Nile on the December 7th and 13th, and moving to Khartoum and El Obeid on December 14th. The NISS led the response. At least 19 fatalities were reported. In the last week of December, doctors, pharmacy workers and journalists went on strike nationwide, whilst arrests of senior opposition politicians and civil society actors increased.