Earlier this month in Yemen, five foreign experts working for the Saudi-funded Masam demining project died while transporting mines from the organization’s headquarters in Marib. A mine they were carrying went off in the truck, causing a powerful blast that killed the five men and injured another (BBC, 22 January 2019). This incident, however, is not isolated and is revealing of the wider risk that largely unmapped mines and improvised explosive devices (IEDs) continue to pose to Yemeni civilians countrywide. According to some estimates, Houthi forces have laid more than a million land and sea mines since the war started, turning Yemen into “the most-mined nation since World War II” (Associated Press, 24 December 2018).

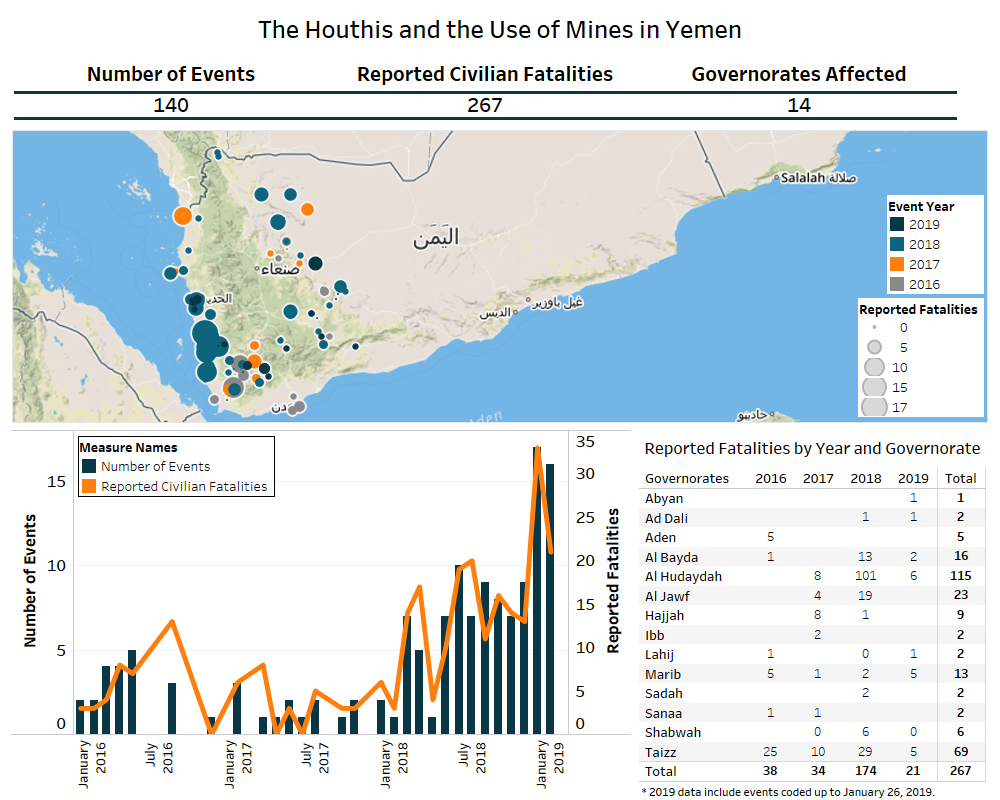

ACLED records at least 267 civilian fatalities in 140 reported incidents attributed to Houthi-planted mines and IEDs since 2016. Yet Saudi sources claim that up to 920 civilians may have been killed, along with thousands injured and maimed, since 2014 (Masam, 2 January 2019; Arab News, 22 January 2019). Mine blasts have intensified since a coalition of Emirati-backed Yemeni forces started a military campaign in the western province of Hodeidah, which accounts for nearly 60% of total civilian deaths linked to mines planted by the Houthis in 2018 (ACLED, 6 June 2018). Mine incidents have gradually increased over the past year, peaking in December 2018 and January 2019, the deadliest months since ACLED started to record violent events in Yemen.

A closer look at the data, however, could help explain the drivers behind this increase. Between January and May last year, Houthi-planted mines reportedly killed an average of three civilians each month in Hodeidah. After the Emirati-backed offensive, the figure jumped to 12 between June and December 2018, marking a significant 279% increase. The districts of At Tuhayat, Ad Durahyimi, Al Khawkhah, and Hays – all situated south of Hodeidah – account for more than 70% of the total mine incidents recorded across the province. This spike does not appear to be a mere byproduct of flaring violence, but rather seems to replicate a pattern observed in Aden in 2015, when Houthi-Saleh forces retreating from the southern port city indiscriminately deployed thousands of anti-personnel and anti-tank landmines to obstruct the movement of troops (UN Security Council S/2016/73: 36).

In addition to spreading insecurity, the pervasive use of explosive devices is also impairing economic activity. Landmines disseminated in grazing lands have frequently hit farmers and animals, which constitute the main source of livelihood for many families in rural areas (Masam, 12 December 2018). In the Red Sea, the Houthis have reportedly laid sea mines threatening commercial shipping and fishermen, who already face the constant threat of air strikes (Al Jazeera, 30 November 2018; New York Times, 17 December 2018). According to ACLED data, improvised sea mines have killed at least 13 fishermen off the coast of Hodeidah since last July. Republican Guard forces, which operate under the command of Tareq Saleh, also found IEDs in the Red Sea Mills, a key granary situated in the eastern outskirts of Hodeidah that is used to stock large quantities of wheat destined for the civilian population (Belqees TV, 10 December 2018). Although the Houthis reject claims of using anti-personnel mines, and instead attribute civilian casualties to unexploded munitions dropped by the Saudi-led coalition, the indiscriminate use of mines and IEDs is contributing to civilian suffering, while also constituting a violation of the principles of distinction, proportionality, and precaution as laid out in humanitarian international law.

Find an explanation of ACLED’s methodology for monitoring the conflict in Yemen here.