The first anniversary of Iraq’s ‘victory’ over the Islamic State (IS) was celebrated on 10 December 2018. However, the events of the civil war continue to influence modern conflict in Iraq to a significant degree. Stalled rebuilding efforts, the continued internal displacement of citizens, and rivalries between former wartime allies are being exploited by the remaining elements of the Islamic State (IS) to operate a renewed insurgency. This can be seen by the tactics now employed by the group, which are similar to those used during its early pre-2014 insurgency[1] (for more information, see this ACLED piece). Ambush attacks, assassinations, and remote IED attacks aim to target local leaders and civilians as a means of amplifying the unrest that has been indicative of the post-war conflict.

Earlier this week, ACLED released supplemental data coded from a number of Arabic language sources covering the 2016 period of the Iraqi civil war. These new data have allowed us to analyze trends concerning both the large-scale operations to retake IS-controlled territory – mostly in Ninewa and Anbar – as well as the continued cooperation of state-allied armed groups, and their individual activity. The fractured nature of Iraq’s ethnic and religious landscape meant that, while working towards the common goal of expelling IS, these groups also used the opportunity to gain influence and control of certain territories with the hopes of retaining it post-war. Both Kurdish forces and members of the Iran-backed Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) continue to exert control and influence, to varying degrees, over territories recaptured during the civil war. This puts the central government in a precarious position as it aims to deal with both civil unrest and attempts by IS to reconstitute itself while also maintaining a check on its allies.

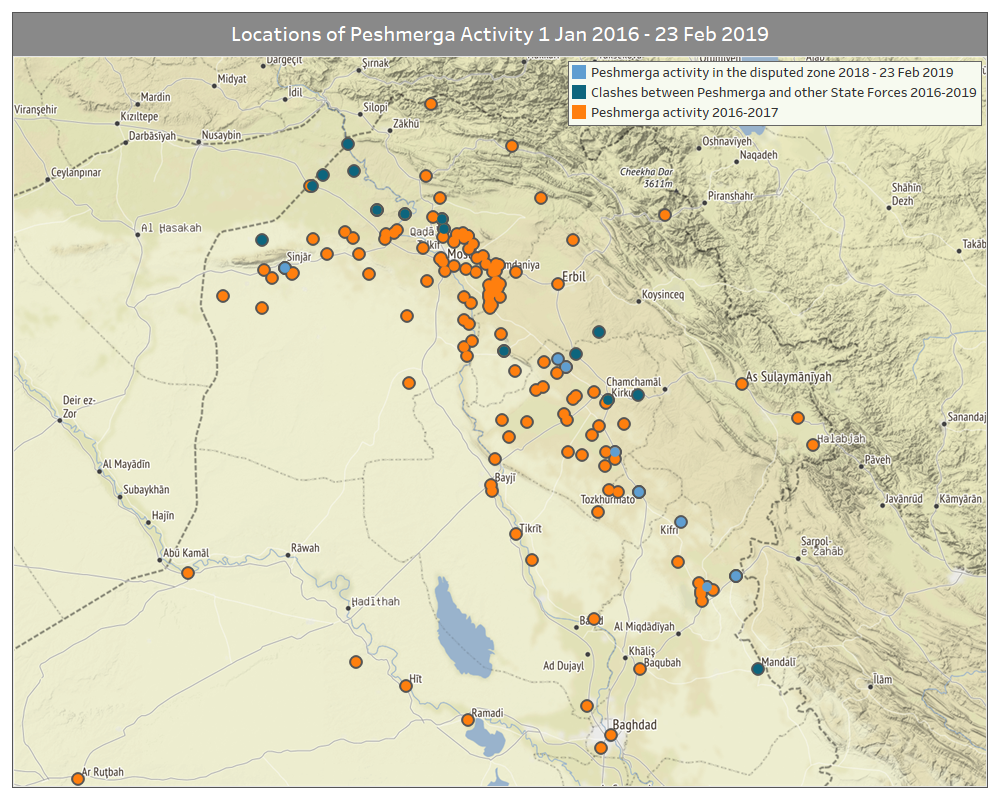

In the north, Peshmerga soldiers of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) gained control of much of the disputed territory south of Iraqi Kurdistan between 2014 and 2017. This territory has been an ongoing concern for both the Kurds and the Iraqi central government, as its inhabitants are primarily non-Arabs, with Kurds making up a large proportion. A strategy of Arabization[2] was employed under Ba’athist party rule from the 1960’s to early 2000’s – particularly in areas of economic importance, such as the oil fields surrounding Kirkuk city – and again by the current government after Kirkuk was recaptured during the 2017 Iraqi-Kurdish conflict (Rudaw, 8 August 2018). This latter conflict was a turning point for Kurdish fortunes, as most of their gains were lost and the relationship with the central government – as well as the PMF, who led the majority of operations – strained even further (Reuters, 11 May 2018). Despite this setback, Kurdish forces still have a small presence in several areas of the disputed territory, as of 2018 through much of February 2019 (see light blue dots on map below).

The PMF, on the other hand, have been more successful in retaining power. The PMF is an umbrella organization of dozens of militias, the majority of which are Shiite, who mobilized in 2014 following the collapse of the Iraqi security apparatus (Carnegie MEC, 28 April 2017). The group was instrumental in the fight against IS, and continues to be employed by the Iraqi state as a means to supplement their security force – despite initial plans by then Prime Minister al-Abadi to dissolve the group following the war (Reuters, 4 January 2018). These initial efforts were met with resistance from the paramilitary force, which rejected the Prime Minister’s decrees, and offered its own vision of the future. Rather than a formal integration, the PMF desired to be an institutionalized autonomous group, with the tacit backing of the local population, and which would fall under the Prime Minister’s Office rather than the Ministry of Defense or the Ministry of Interior. This came true in March 2018, when PM al-Abadi formalized the group’s inclusion into the armed forces under their own terms (Alaraby, 9 March 2018). In August 2018, hundreds of citizens demonstrated in Mosul for the PMF to remain stationed there, denoting the current importance of the group as part of the larger Iraqi security apparatus (Iraqi News, 14 August 2018). On the other hand, PMF soldiers have regularly been accused of abusing civilians in areas that they occupy (GPPI, 18 February 2019).

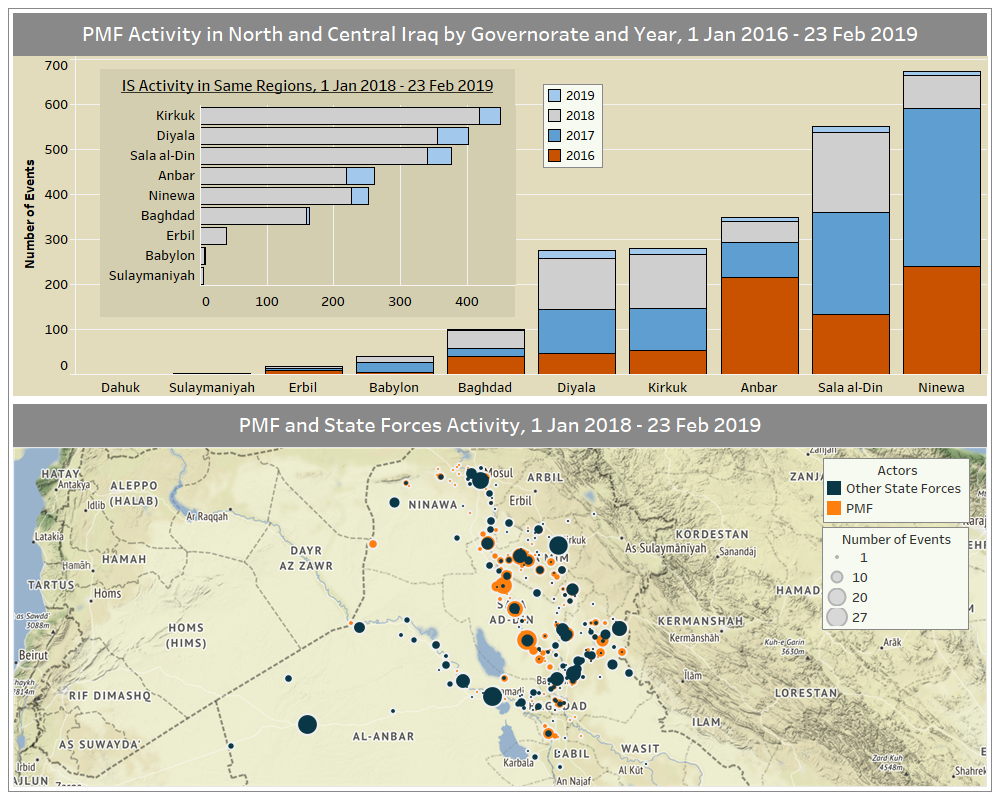

The primary graph below shows the number of events in which the PMF have been involved between 1 January 2016 and 23 February 2019. Militia fighters are still very active, particularly in the governorates of Sala al-Din, Kirkuk, and Diyala; these are the same regions where the IS insurgency is now most active (see inset graph below). In many areas, particularly in Sala al-Din, PMF have replaced state forces as the main security force. These areas are visible as orange on the map below.

As of the 2018 general election, the PMF have the backing of the new Prime Minister Abdul-Mahdi (Kurdistan 24, 5 November 2018), although controlling the group will be difficult given that they are not a single entity. More recently, leaders of the group have been attempting to gain political legitimacy apart from being recognized as an official group within the Iraqi state forces. A significant number of PMF leaders gained parliamentary positions in the May election (Washington Institute, 11 June 2018), while this month there have been attempts to purge dissident elements from the group (Al-Monitor, 21 February 2019).

With the PMF gaining more power, there are concerns that the group’s sectarian roots and ties to Iran may lead to further divisions both within the armed forces and the state in general (Washington Post, 9 January 2019). This, along with Kurdish resentment and continued desire to gain claimed territories in the disputed zone, is a challenge to the central government as it attempts to maintain a firm control of the country. No doubt the Islamic State is taking advantage of the central government’s numerous distractions as a means to grow its insurgency. Much of the reconstruction effort remains unfinished, partly due to a lack of funds alongside state corruption. A growing discontent of the state could lead disenfranchised locals to support opposition groups like IS (Fanack, 21 May 2018). 2018 in particular was distinguished by a growing number of demonstrations, particularly in the south, where people protested against the state’s lack of focus on economic and social grievances (for more on that, see this ACLED piece). Rebuilding infrastructure, as well as the trust of the people, will be paramount to staving off another Iraqi civil war.

Notes:

[1] ACLED Iraq data currently only cover the period ranging from 1 January 2016 to 23 February 2019. The trends denoted here are based on those referenced by the Combating Terrorism Centre, December 2017.

[2] A process by which a non-Arab majority culture group is supplanted as the dominant group by Arabs through a variety of means; in this case by forced displacement of native groups, as well as the introduction of large Arab settler populations.