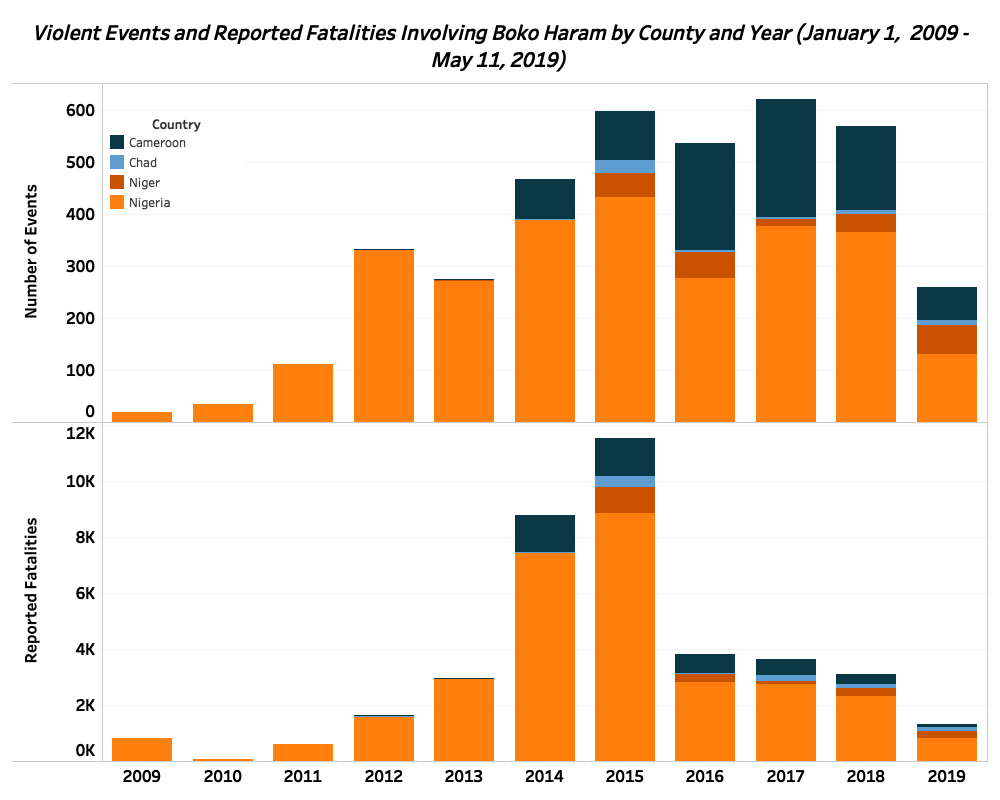

Since emerging in Borno State in North East Nigeria in 2009, the vast majority of Boko Haram’s violent activities have been concentrated in Nigeria. In the ten years the group has been active, more than 70% of violent events associated with the group and 80% of the associated reported fatalities have taken place in Nigeria. This pattern appears to be shifting in 2019, as more of Boko Haram’s violent activities are occurring outside of Nigeria. In 2019 to date, only half (50.4%) of violent activities associated with Boko Haram (both the Shekau and Barnawi factions) have been in Nigeria (see ACLED, 10 April 2019 for discussion of these separate factions). Unlike previous instances in which Boko Haram engaged in significant activity outside of Nigeria, the 2019 expansion of Boko Haram’s violent activities into neighboring countries, and the types of violence it is engaging in, allude to a resilient and resourceful insurgency. Increasing violence associated with Boko Haram in Niger, Chad, and Cameroon has dire implications for the humanitarian crisis in the Lake Chad Basin and stabilization efforts in the region.

Boko Haram in Niger, Chad, and Cameroon

Boko Haram first expanded outside of Nigeria in 2012, when it was involved in two violent events in Cameroon and Chad. The event in Chad was a skirmish between Nigerian military forces and militants involved in a smuggling operation; the event in Cameroon was an attack launched by the militants on a border town in which no Cameroonian nationals were among the 15 reported fatalities. Nigerians remained the primary opponents in these events. By 2013, however, these cross-border operations were focused on non-Nigerian targets; in June 2013, for example, Boko Haram militants attacked a prison in Niamey, Niger, which resulted in three reported fatalities and three injured prison guards. Though Boko Haram has continuously engaged in cross-border operations since 2012, the majority of violent events involving the group (nearly 72%) and associated reported fatalities (81%) have remained in Nigeria (see graph below).

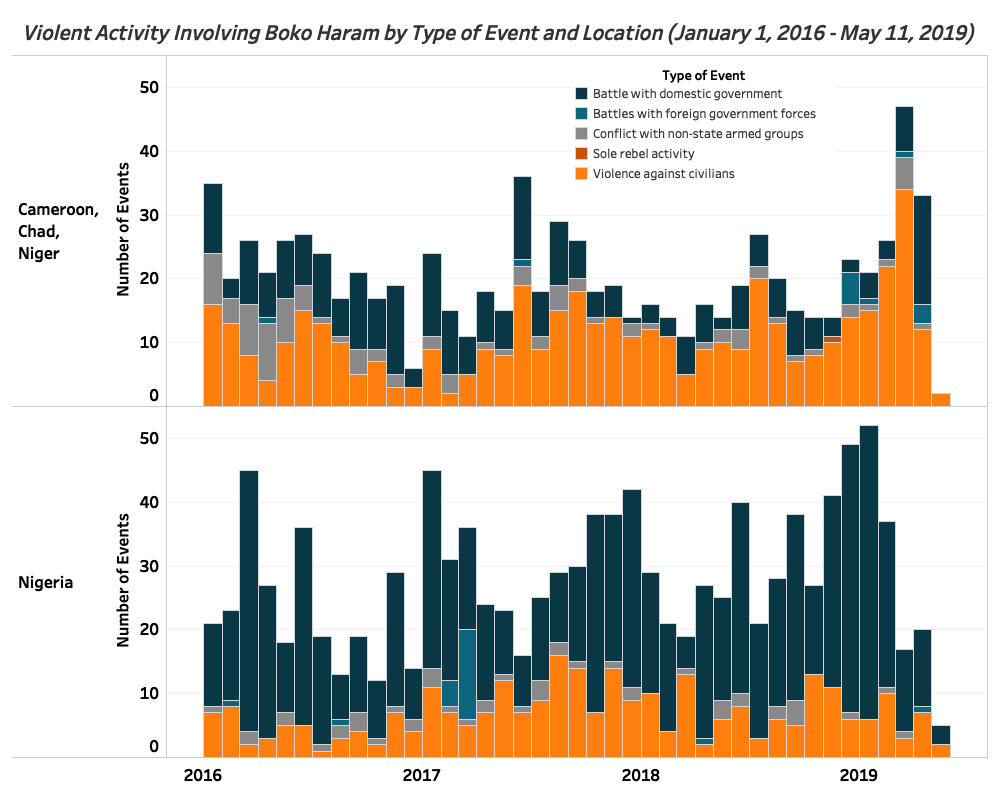

As Boko Haram has continued to engage in operations in Chad, Cameroon, and Niger, different patterns of violence have developed in each country. 52% of events involving the group in Nigeria are battles and 30% are violence against civilians. Whereas in Chad, nearly 60% of the violent events associated with Boko Haram have been battles; in Cameroon the proportion is just less than 40%; and in Niger it is 48%. In Niger and Cameroon, Boko Haram is engaged in proportionally more violence against civilians (39% and 41%, respectively). This pattern may be a function of Chad’s more robust security sector and the proximity of the Chadian capital (N’djamena) to the conflict, as compared to the capitals of Nigeria, Niger, and Cameroon, which makes confining Boko Haram a more acute problem for the Chadian state.

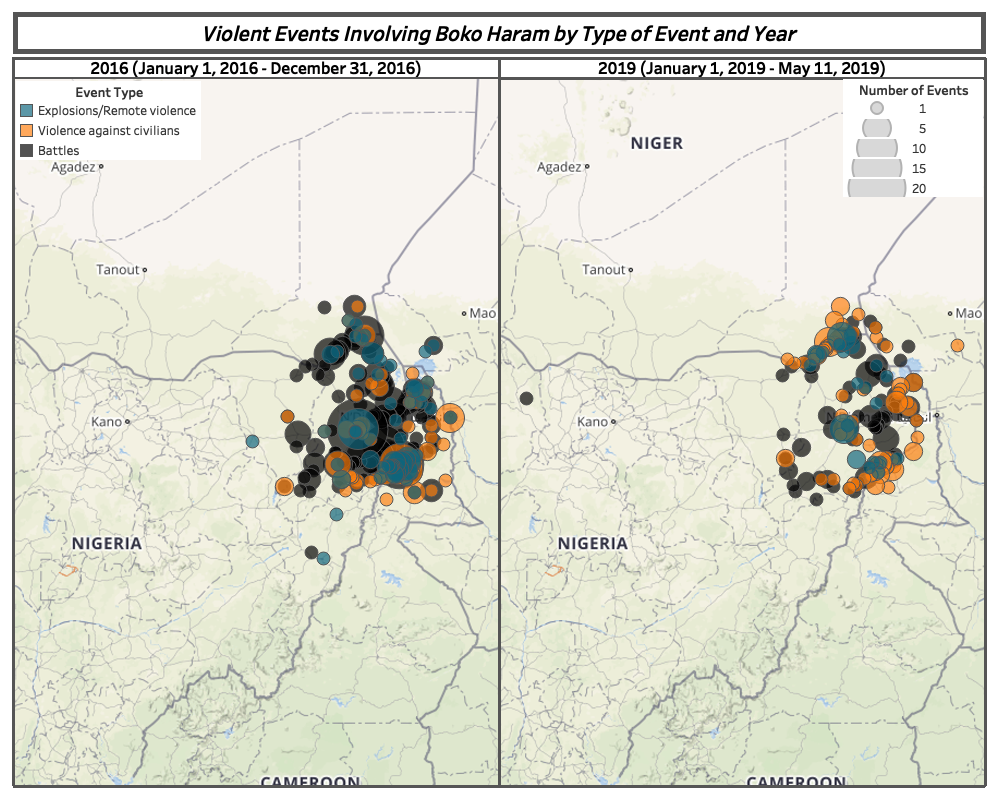

So far in 2019, nearly half of all violent events involving the group have occurred outside of Nigeria – a proportion that is unusually high for the group. Boko Haram’s geographic pattern of activity in 2019 thus far resembles 2016, when almost 48% of the group’s activities where outside of Nigeria.

2016 Redux?

The 2016 geographic expansion came in the face of a renewed military effort that successfully dislodged the group from its territorial holdings in North East Nigeria (BBC, December 24, 2016). As demonstrated below, the surge in Boko Haram’s activity outside of Nigeria in 2019 came after a number of clashes with the Nigerian military between December 2018 – February 2019. This pressure, like in 2016, may have incentivized Boko Haram to shift its activities beyond Nigeria’s borders.

The composition of Boko Haram’s operations outside of Nigeria are significantly different between the group’s 2016 and 2019 geographic expansions. 31% of events in 2016 were comprised of violence against civilians and 29% were battles with government forces; in 2019, 64% are violence against civilians and 18% are battles with government forces. Violence against civilians may be a strategy adopted by the insurgents to maintain an operational presence in these areas without bearing the risk that comes with confronting state security forces. The prevalence of violence against civilians, as compared to clashes with state security forces, suggests that Boko Haram is in greater control of where and when it engages in violent activities in 2019 than in 2016. This strategy may be at play whether the violence against civilians is being adopted in response to degraded insurgent capacity (Wood 2010) or because Boko Haram is the most violent armed group in the area and is less reliant on civilian support (Dowd 2019). This prevalence of violence against civilians in recent months also suggests an anemic state response to Boko Haram’s activities outside of Nigeria.

Of particular note is the prevalence of abductions outside of Nigeria. In 2019 the number of abductions outside of Nigeria (16) has already surpassed the total number of such events in 2016 (14); abductions account for nearly 19% of the violence against civilian events outside of Nigeria in 2019 thus far.

It may be that Boko Haram is using violence against civilians in response to competition with other armed groups (Raleigh 2012). Some have suggested that there is factional competition within Boko Haram, pitting the faction lead by Barnawi (and reportedly backed by the Islamic State) against the faction lead by Shekau (Mahmood and Ani 2018). There have only been two reported instances in 2019 thus far, however, of clashes between Barnawi and Shekau’s factions. It seems likely, then, that Boko Haram is engaging in kidnappings to bolster its ranks, and contribute to an atmosphere of pervasive insecurity, and is engaging in attacks on civilians to create new frontlines in the conflict (Raleigh 2012).

Conclusion

A significant proportion of Boko Haram’s violent activities in 2019 thus far have taken place outside of Nigeria. Though the last time we saw such a geographic expansion it was in response to an effective military offensive, the prevalence of operations outside of Nigeria in 2019 does not signal insurgent weakness. Rather, Boko Haram appears to be exploiting porous border and security gaps in neighboring countries to advance its interests and bolster its ranks. Though Boko Haram’s spread into neighboring countries in both 2016 and 2019 followed an increase in the number of battles between the rebels and the Nigerian military, in 2019, this shift has placed civilians directly into the line of fire. Despite surface-level similarities between event trends in 2016 and today, these two periods are actually exhibit very different patterns of violence, with a less significant state response to Boko Haram’s activities outside of Nigeria – and as such, the results can be expected to diverge dramatically in the coming months.

© 2019 Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). All rights reserved.