In recent weeks, a series of attacks on churches in Burkina Faso has received global media coverage (BBC, 2019). Jihadi militant groups recently accused of pitting ethnic communities against each other (HRW, 2019) are now also accused of trying to ignite a religious war (La Croix, 2019). While jihadists do play a crucial role in the conflict in the region, focusing solely on these groups ignores the state’s role in the brutality. These church attacks not only reflect the growing capacity of jihadists in the region, but the states’ scorched-earth tactics — a fact the media has failed to highlight.

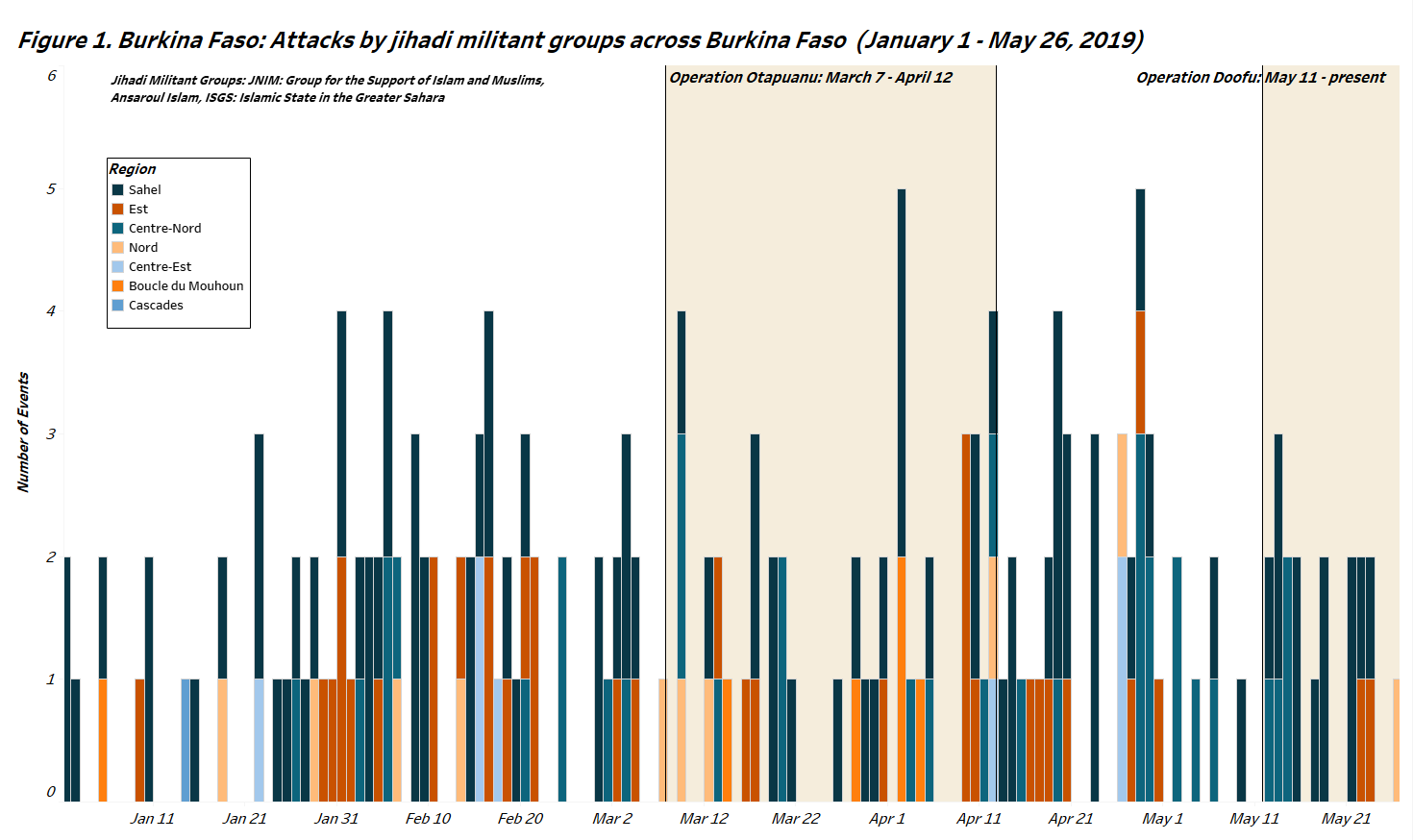

The attacks in Burkina Faso have roots in neighboring Mali. The conflict in Mali has entered its eighth consecutive year and rages on despite multiple intervening efforts by French, UN, and regional forces. The conflict mutates as it spreads, and is becoming more brutal. Local populations in Mali have found themselves pinned between repressive government forces, ethnic-based militias, and jihadi militants. Violence in the neighboring countries of Burkina Faso and Niger has correspondingly evolved from mere spillover conflicts into full-fledged insurgencies (ACLED, 2019) in which mass-atrocities and summary executions have become standard practice (Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide, 2018). As of May 25, there were as many political violence events perpetrated by jihadi militant groups in Burkina Faso during 2019 than in the entirety of 2018. In early March, Burkinabe forces launched Operation Otapuanu in the country’s eastern regions in an attempt to quell the fighting. Despite being touted as a major success, the operation resulted in only temporary withdrawal by militants from the region, and in a corresponding increase in attacks elsewhere in the country — as shown in Figure 1 below (ACLED, 2018).

The increasing scope of the conflict — as demonstrated by these recent attacks on churches — reflects the behavior of regional states, more than the armed groups they fight. States in the region have failed to protect particular communities and, in doing so, fueled conflict, militancy, and insecurity through their use of ethnic-based militias. These militias operate in tandem with government forces, and occasionally with international forces. This was the case during the 2018 offensive in the Mali-Niger borderlands, which exacerbated tensions along ethnic fault lines and prompted mass-atrocities (ACLED, 2018). Similar events occurred in Mali’s “Pays Dogon” where Dozo militiamen allegedly massacred Fulani in Kologoun-Peulh and Ogossagou(RFI, 2019). In Burkina Faso, Koglweogo militiamen committed a massacre of Fulani in Yirgou and neighboring areas (VOA Afrique, 2019). Certainly, jihadi militants do exacerbate cleavages (The Conversation, 2019). However, by favouring certain communities and associated armed groups while stigmatizing and persecuting others, governments in Burkina Faso and Mali spur vicious cycles of violence amongst communities.

The attacks on churches in Burkina Faso are in fact reactions to the scorched-earth tactics of the state, and the militias they work alongside. Over the past months, attacks targeting the Christian community have been recorded in Sergoussouma, Boukouma, Silgadji, Dablo, Kayon, and Toulfé (see Figure 2 below); all took place in the context of military operations accompanied by grave human rights violations (HRW, 2018). Attacks targeting churches are not a novelty: central Mali saw an analogous trend in 2017 (Jeune Afrique, 2017), and these took place in a similar context. Koglweogo militiamen allegedly aid government forces by identifying members of the — largely Muslim — Fulani community involved in militant activities (Kisal, 2019), behavior that may provoke retribution against the perceived constituency of the Koglweogo. Similarly, the Malian armed forces cooperate with and use Dozos (traditional hunters largely drawn from the Dogon and Bambara communities) as guides and auxiliary forces, often spurring a response against these communities. As a result of this vicious cycle, these conflicts have become increasingly brutalized, intercommunal violence is intensifying, and the actors involved have become more relentless and indiscriminate. These developments have a negative impact on the population, but also on security forces, who face increasing risk of attacks by militants. Security forces have recently abandoned posts in areas under the militant influence such as Déou, Sollé, and Arbinda. In Tongomayel, security forces are forced to close shop in the evening and withdraw to Djibo due to the risk of attacks at night-time.

[Figure 2: missing image]

While church attacks by jihadists in the region make international headlines, similarly brutal tactics by the government and its allies — including summary executions of Fulani — fail to garner the same amount of attention. Nevertheless, this approach by government forces is, in part, the catalyst for violence practiced by militant groups in the region. The government’s tactics enable jihadi militants to present themselves as defenders of certain communities, and fast-track recruitment drives. While large-scale government operations may result in superficial short-term gains, the negative impact on the state’s relationship with the population quickly reverses these gains and causes the exponential expansion of militancy in Burkina Faso.

© 2019 Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). All rights reserved.