This month, Malians will go to the polls to vote in delayed parliamentary elections: voting was originally slated for October 2018, then delayed until November, then delayed until April 2019, before being scheduled for June 2019 (DW, October 16, 2018; GardaWorld). The courts cited “force majeure” (meaning unforeseen circumstances) as the reason for the delays — even though the security situation in the country has been a persistent problem since 2012 and the issues with the implementation of the Algiers peace agreement between the government and northern armed groups are well-documented (AFP, October 16, 2018). In April 2019, Mali’s government was dealt another blow when Prime Minister Soumeylou Boubeye Maiga announced that his government was resigning. Though many have speculated that the resignation was in response to a brutal attack on a Fulani community the month prior, African Arguments concluded that “the massacre and a generally deteriorating security situation was likely only the straw that broke the camel’s back” (African Arguments, April 23, 2019).

The Malian government is now faced with two crises: resolving the conflict in the north and addressing escalating violence in the country’s center. In both regions, the government’s existing efforts to broker peace with non-state armed groups do not address the most relevant sources of violence in recent years.

Violence in Mali Since 2012

Mali’s current security situation can largely be traced back to the events of 2012, when president Amadou Toumani Touré was overthrown in a military coup. Concurrent to the coup, a military offensive by a coalition of jihadist rebel groups and Tuareg separatists successfully took territory in the country’s north and declared the independence of “Azawad.” International intervention and a peace agreement signed in 2015 have helped to quell the insurgency in the north (below).

The most recent election postponement was intended to give the government more time to implement the peace deal brokered between the Malian government, the Coordination of Azawad Movements (CMA) and the Platform of armed groups (the Platform) and address persistent insecurity in the country’s center and north. An independent review of the progress peace agreement, published in February 2019 revealed that 15% of the agreement terms had not been initiated at all since the agreement was signed in 2015. The terms of the agreement associated with political and institutional issues have been particularly neglected — roughly 44% of these reforms have not been initiated and just 6% have been achieved (The Carter Center, February 18, 2019).

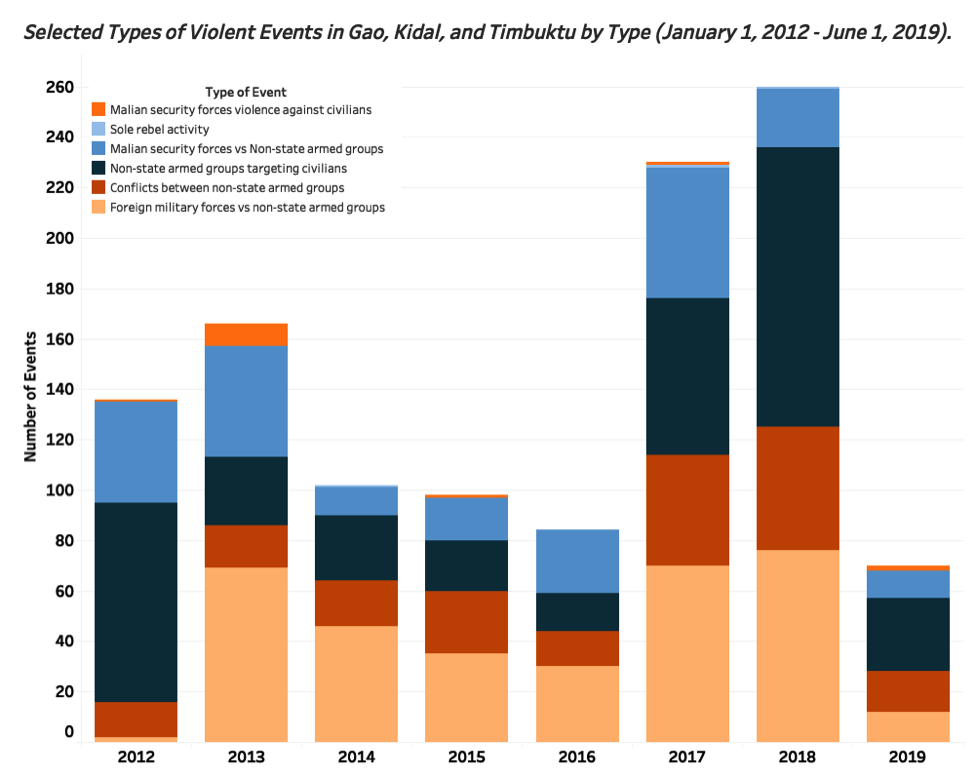

Yet, despite the inadequacies in the implementation of the agreement, the surge in violence since 2017 is not primarily driven by armed groups that are party to the Algiers accords. This pattern is driven by a surge in activity involving Jama’a Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin (JNIM) and the Islamic State in Greater Sahara (ISGS). In 2017 there were more than 50 events involving JNIM; in 2018 there were nearly 80 events involving JNIM and more than 60 involving ISGS. More than 100 of these events, in total, have been violence between these rebel groups and foreign military forces. These groups have been increasingly engaging in violence against civilians. There were just 5 instances of violence against civilians attributed to these groups in 2017, in 2018 that increased to 35 events ( 14 of which were attributed to JNIM and 21 were attributed to ISGS). This surge in the targeting of civilians could be in response to setbacks from confrontations with better equipped foreign militaries or a function of competition with other armed groups in the region. (Raleigh 2012).

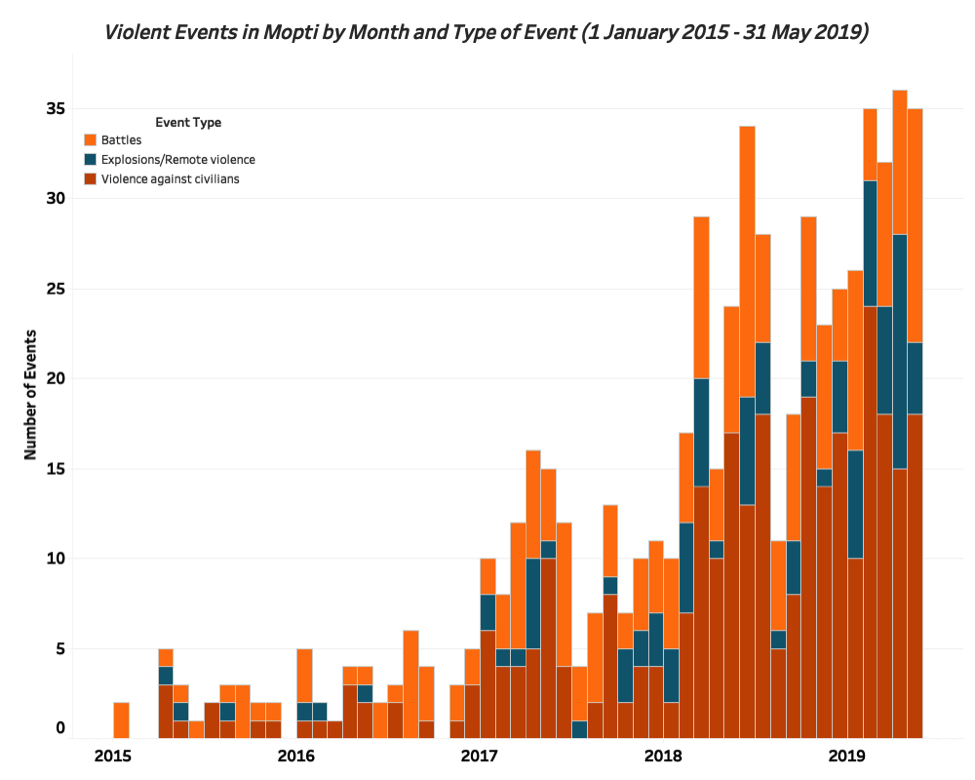

As the country has struggled to resolve the crisis in the north, violence in the country has shifted to the center, where communal violence has surged in Mopti. As demonstrated below, since 2015, violence in Mopti has been on a steady rise. Violence in the region is not only increasing, the proportion of the violence directed against civilians is also increasing. In 2015 the proportion of violence against civilians was less than 40%. In 2018, violence against civilians accounted for nearly 55% of violent events in the region. The number of reported fatalities associated with this violence has also surged; there were more than 430 reported fatalities in Mopti related to violence against civilians in 2018, which is more than a 600% increase from 2017, when there were fewer than 60 reported fatalities from violence against civilians.

Violence in Mopti is often described as “communal violence” (the Conversation, March 29, 2019). These conflicts are fueled by conflict over land use and spirals of retributive violence; some analysts have tied the surge in violence to the peace process’ neglect of the region (International Crisis Group, July 6, 2016).Community defense militias, mobilized to provide for security amidst the violence, have themselves become sources of instability. One such group is Dan Na Ambassagou, a Dogon defense militia, which has been responsible for 19 instances of violence against civilians since 2018. These attacks have resulted in more than 270 reported fatalities. This group is responsible for an attack on a Fulani community in March that resulted in more than 170 reported fatalities across two villages.

In response to the persistent violence, the government launched an “accelerated” disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) program for the country’s center in December 2018. Both this process and a number of local peace agreements have been insufficient to quell the violence (the New Humanitarian, March 6, 2019).

Conclusions

Mali’s upcoming elections have been delayed in order to provide the government time to fully implement the Algiers peace agreement. However, even a more robust implementation of the agreement would not address the increasing violence among groups in the north who are not party to the agreement nor the burgeoning crisis in the country’s center.