Natural disasters — such as hurricanes, floods, and tsunamis — are often used as an impetus for massive policy shifts and redistribution of state resources. Often, sudden changes of government expenditure may contribute to public frustration, particularly when a state’s response to an emergency is seen as ineffective. Indeed, a commonly cited cause for public protest activity is poor state response to natural disasters. However, analysis demonstrates that even far-reaching political responses to natural disasters often provoke violent demonstrations, indicating that promises made during high-level visits in affected areas raise expectations among natural disaster victims. If those expectations are not then met, discontent can trigger episodes of riots and protest – regardless of the rapidity or quality of the response. Thus, ‘band-aid’ policy fixes are not enough to reduce riot and protest events in the aftermath of natural disasters: consistently inclusive and sustainable policies are required to effectively reduce those events.

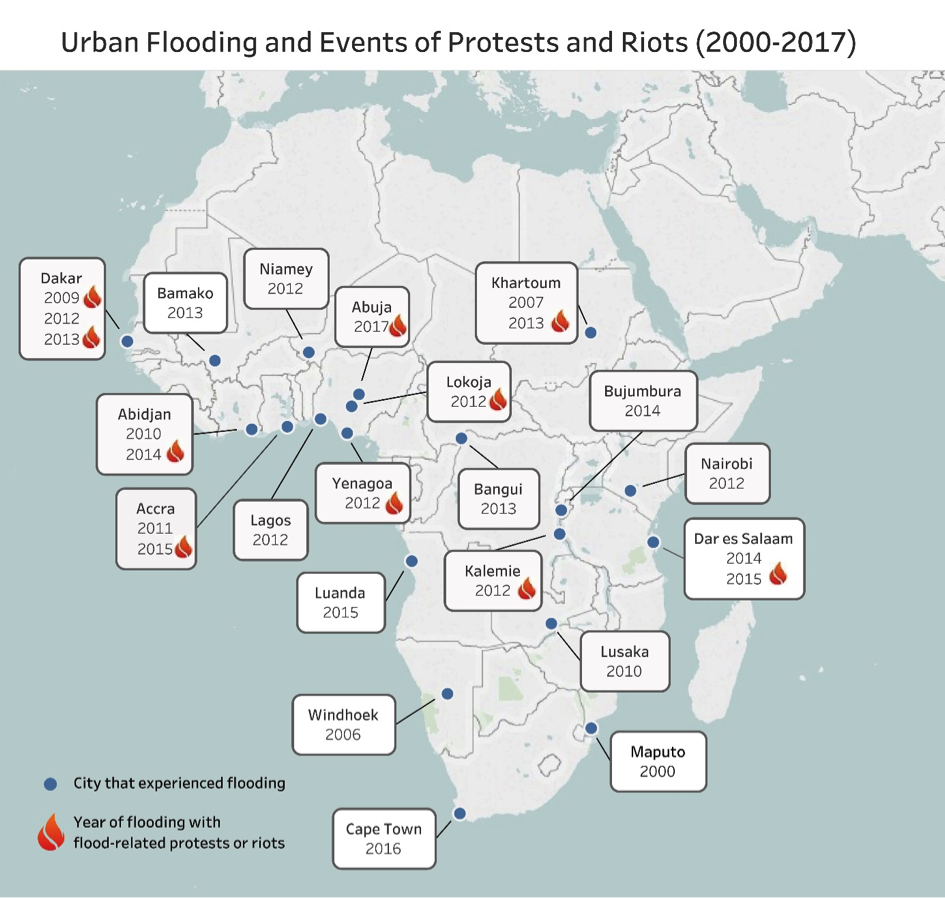

This thesis is suggested by a larger qualitative comparative analysis study (Plänitz, forthcoming) which examines the level of demonstration events following 26 cases of flooding across the African continent: while ten of these disasters were followed by high levels of protest and riot events, the others were not (see map below). In an attempt to examine these differences, a set of conditions and models are tested (see Plänitz, forthcoming for more information). The results suggest that in the ten cases with significant post-flood riot and protest events, high-level state institutions were quick to respond and pledge support. In cases without significant demonstration events, the response was considered more reserved, and high-level officials refrained from making financial pledges. Contrary to popular belief, the study suggests that prompt and substantial policy responses to flooding and other natural disasters may in fact provoke increased political disorder if not followed by action.

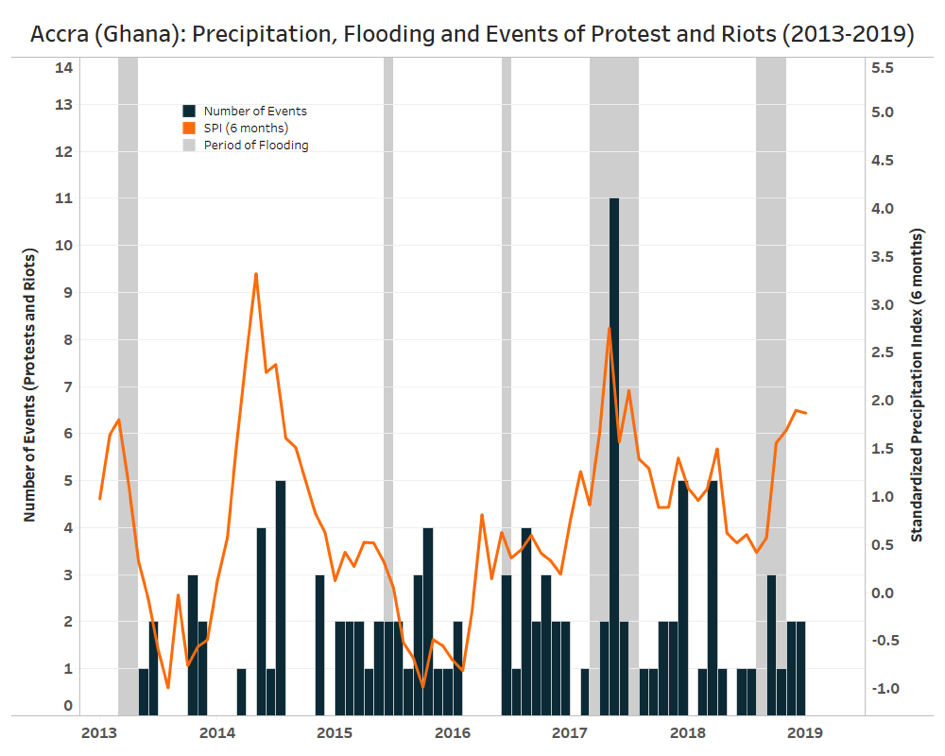

Flooding in the Ghanaian capital of Accra serves as a prime example of this phenomenon. The city experiences yearly flooding, leading to several affected communities within the metropolis. ACLED data and climate information gathered from the Emergency Events Database (EM-DAT) and the African Drought and Flood Monitor indicate levels of riot and protest events in Accra trend higher in times of abundant rainfall (see graph below). This phenomenon can be observed for the summers of 2014 and 2017, where above-average levels of public unrest occurred in the form of demonstration events during periods of high precipitation, even absent flooding. Figures on rainfall are given as 6-month Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI). The Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) is one of the most common climatological precipitation indices for the identification of precipitation surpluses and deficits. It serves to evaluate and characterize the precipitation ratios of a month, quarter or half-year in relation to the respective normal values. However, precipitation levels and even natural disasters do not result in increased protest and riot events. People do not protest natural disasters; they march to express their discontent with policies and actions taken by state institutions around the event.

Therefore, in examining the relationship between natural disasters and demonstration levels, policy responses – rather than the flooding itself – must be examined. Differences are evident when examining demonstration levels surrounding two floods in Accra – one of which is linked to increased demonstration levels, and one which is not. While in the case of the 2011 flood, administrative responses did not lead to civic unrest, there were higher-than-average levels of protest events in the aftermath of the Accra flood of 2015.

Due to heavy rain, large parts of Greater Accra and Eastern parts of Ghana suffered inundation in October 2011. Within Greater Accra, floods impacted residential and low-income neighborhoods from the East (e.g. Tema, Osu Klottey) to the West (e.g. Ablekuma) (NADMO, 2011). According to figures published by National Disaster Management Organisation (NADMO), a total of 43,098 people were directly affected by flooding in the capital region in 2011(NADMO, 2011). In an effort to prevent future flooding, the national government made an appeal to the international community to refurbish Accra’s storm drains (Government of Ghana, 2011). President Mills visited flooded parts of Accra but refrained from making concrete statements on state support or relief funds. In the aftermath of the flooding, no incidents of riots and protest were reported to have occurred (see graph above).

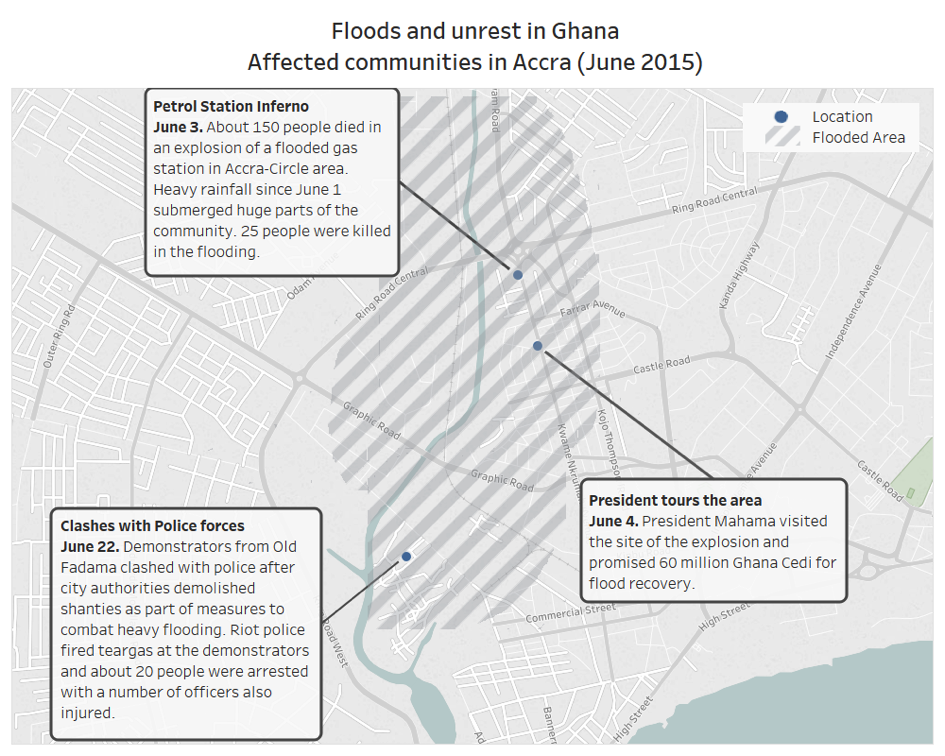

Almost four years later, a period of rain in June 2015 submerged parts of Greater Accra near the Odaw drain (see map below). Among those badly hit areas that are marked on the map (see map below) were Kaneshie, Circle and Old Fadama (IRIN, 2015; UNCT, 2015). The Red Cross estimated that up to 46,370 people were affected in some way (IFRC, 2015). According to the Inter-Agency Working Group for Emergencies, 9,255 were displaced (IFRC, 2015) and 175 people were killed when a gas station, submerged in the flood waters, detonated. As a response to the flood, President Mahama promised 60 million Ghana Cedi (about 11 million USD) for relief operations and repair of infrastructure for flood prevention (Graphic, 2018). Later in June, a demolition exercise in Old Fadama initiated by the Accra city authorities to remove structures in flood-prone areas sparked clashes between police and demonstrators. Many of the residents did not receive financial compensation and were confronted with the decision taken by the administration. On June 22, riot police used tear gas and arrested 20 people (see graph above) in Accra.

The two episodes of flooding led to displacements and devastated communities in Accra but are different in a critical point – the nature of the political response. While many conditions in 2011 and 2015 were comparable – such as the presence of youth, political representation, or socio-economic inequality – it was the political response that differed. In 2011, President Mills avoided mentioning relief funds or concrete amounts of money dispersed to victims. During his tour to affected neighborhoods, President Mahama in 2016 promised 60 million Ghana Cedi and raised expectations among the affected citizens. This case study is one of 24 outlined in the larger research project (Plänitz, forthcoming), suggesting that protest and riots seem to channel anger resulting from missed expectations and discontent that were seeded by presidential visits and their unfulfilled promises. While it is certainly positive for administrative government to provide rapid and effective relief to communities victimized by natural disasters, the work does not stop there: the only real solution to prevent discontent, especially in the form of violent rioting, is administrative follow-through. Once promises are not transformed into a sustainable policy that improves the livelihoods of affected citizens, or once decisions around post-flood policy are neither based on inclusive processes nor designed in cooperation with local communities, the risk of protest and riot events prevails.