Renewed attention on southern Yemen has largely obscured recent political developments in the north of the country, where over the past year the Houthis have faced scattered, yet increasing opposition to their pervasive rule. This localized dissent generated a sequence of violent incidents and a spike in infighting, which is at its highest levels since the alliance with former president Ali Abdullah Saleh crumbled in December 2017. These events point to the highly volatile and unstable nature of the Houthi governance system across northern Yemen, and questions their ability to run politics in times of de-escalating conflict.

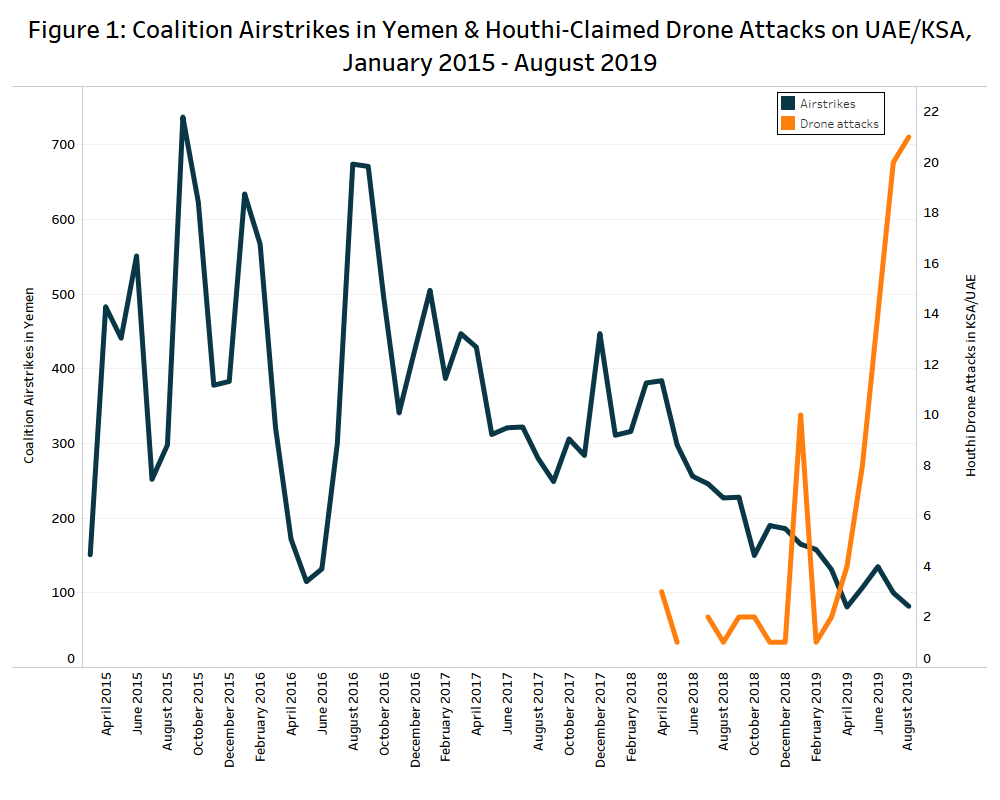

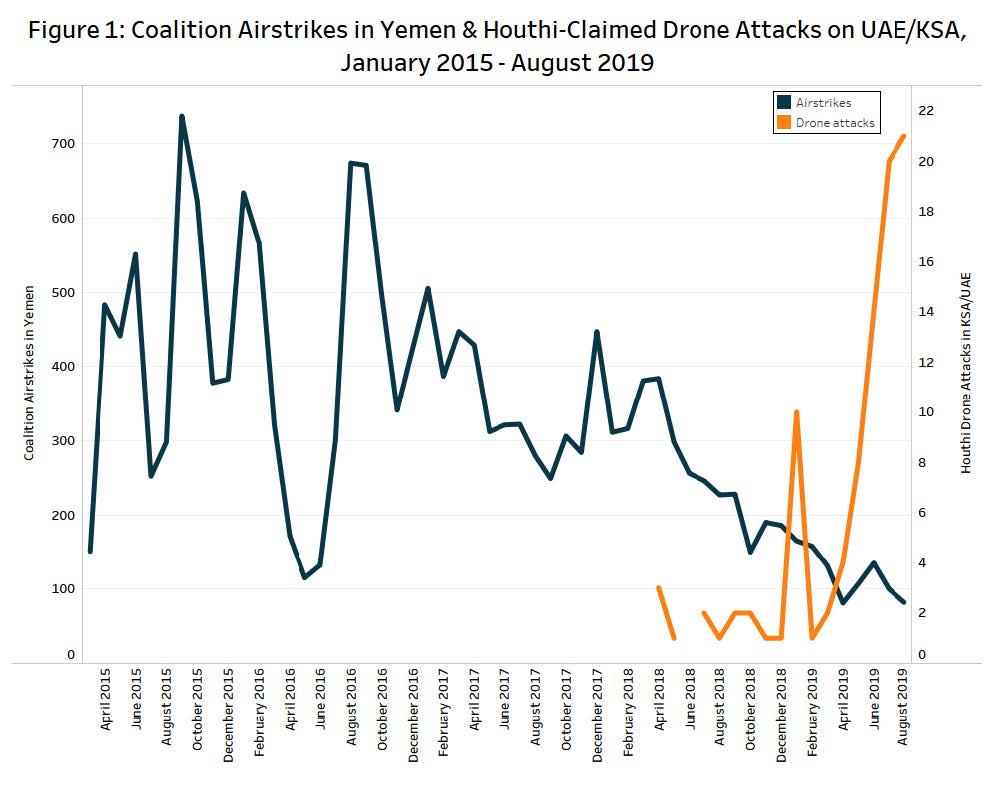

Conflict since the December 2018 Stockholm agreement has assumed various forms. The agreement averted a looming military offensive with potentially disastrous consequences and led to a stagnation in the conflict between Houthis against the coalition-backed forces; although few territorial changes have occurred between these forces, they are firmly entrenched where they were a year ago. The agreement contributed to a significant decline in combat fatalities along the west coast, but violence has surged in other governorates, including Hajjah, Ad Dali and Taizz (ACLED, 18 June 2019). Simultaneously, despite the Saudi-led coalition’s intention of gradually disengaging from direct military operations, reflected in a consistent decrease in the number of airstrikes recorded since last year and culminated in the UAE’s drawdown announced last June, the Houthis have claimed an increasing number of attacks against Saudi and Emirati facilities (see Figure 1).

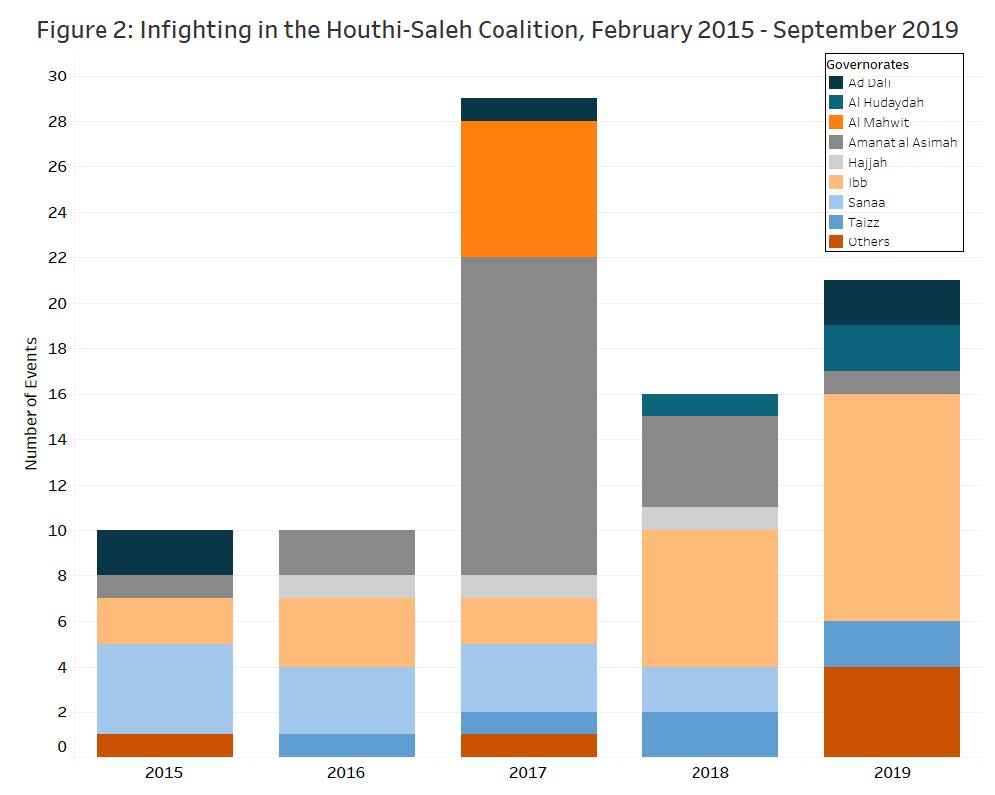

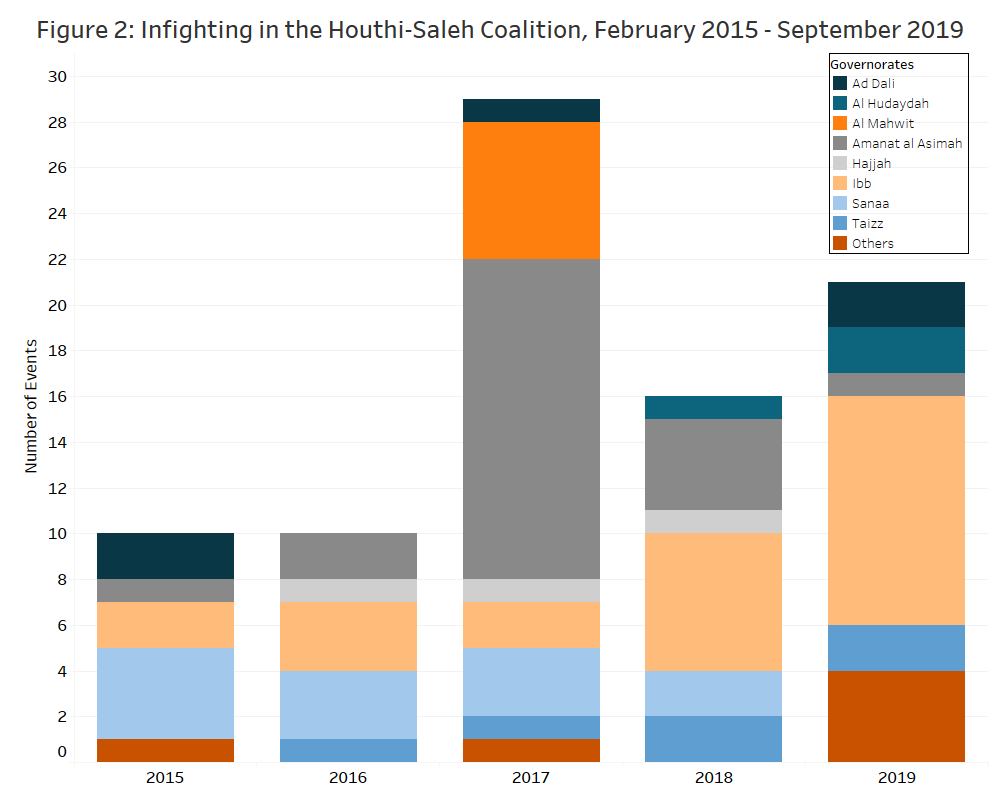

While the conflict is drawn into stagnation, the Houthis have faced isolated pockets of rebellion from within their own ranks as well as from tribes and communal groups opposed to their rule. Included in these episodes is the quashed rebellion of the Hujur tribes in Hajjah, triggered by the Houthis’ alleged invasion of tribal territory earlier this year (al-Deen, 23 April 2019), as well as a string of clashes in Amran that culminated with the killing of a tribal leader the Houthis accused of defection in July (The National, 23 July 2019). Throughout 2019, sporadic factional clashes occurred in Ad Dali and Taizz, but the province of Ibb reported the highest levels of infighting between opposing Houthi factions in northern Yemen, marking a record high since the split with Saleh in 2017 (see Figure 2).1Data only include events involving state forces affiliated with the Sana’a-based government.

How the Houthis Seized Ibb

Strategically located on the highlands of central Yemen along lucrative wartime smuggling routes, Ibb is the second most populous governorate of the country, home to nearly 4 million people and sheltering more than 200,000 IDPs (International Organization for Migration, 11 March 2019). The vast majority of the local population adheres to the Shafi‘i Sunni school of Islam, but Zaydi minorities are scattered in the province and largely concentrated in the ‘hijras’— protected enclaves within tribal territory mostly inhabited by sayyids, the descendants of the Prophet Muhammad.

Though scarcely penetrated by Zaydi religious and cultural centers, Ibb was the first governorate outside the far north to witness clashes between the Houthis and Islah during the summer of 2013. In July that year, skirmishes erupted in the ar-Radhma district, located in the north-east of Ibb at the crossroad between four governorates and a Zaydi enclave (al-Heyad, 20 August 2013). Hashemites from local hijras (al-Manjar in Bani Qays and adh-Dhari in Shayzar) operated as a Houthi foothold by establishing checkpoints to protect a Shiite religious festival celebrating the martyrdom of Ali Ibn Abu Talib. Violence escalated as members of the prominent Du‘am family, a lineage of shaykhs unofficially affiliated with the anti-Houthi Islah party, demanded to lift the checkpoints. An agreement was brokered by a local mediation committee led by Abdulkarim ash-Shahiri, paramount shaykh of the central areas.

In October 2014, the Houthis overran al-Hudaydah and Dhamar; soon after they entered the city of Ibb from a northern checkpoint without facing resistance from the government forces. The Local Security Committee held a meeting at the presence of Abdulmushin at-Tawwus, an in-law of the movement’s leader Abdulmalik al-Houthi and the Houthi appointed supervisor (mushrif) for the governorate (al-Jazeera, 15 October 2014). A ten-member tribal mediation committee was established, led by the deputy governor of Ibb and president of the General People’s Congress’s (GPC) local branch shaykh Abdulwahid Salah.

The full takeover of Ibb governorate also encountered little resistance. Sporadic clashes with Islah took place in the north-eastern districts of Yarim and ar-Radhma (Sabq,18 October 2014), and around the governorate’s capital city (al-Jazeera, 17 October 2014). Local resistance mobilized around the Du‘am family and the Islah party, finding a leader in shaykh Abdulkarim ash-Shahiri. After the Houthis succeeded in crushing the resistance forces in ar-Radhma and destroyed Du‘am family’s house (al-Araby, 29 October 2014), its members agreed to leave the province and joined the ranks of the internationally recognized government.

This rapid advance across the governorate was facilitated by a strategic alliance with the former president Saleh’s GPC, which secured the support of the 35th and 55th brigades of the Republican Guard and a direct access to local tribal networks. Yet from the very beginning, the Houthis worked to eradicate the GPC and coopt their networks. Some key GPC deputy governors were confirmed in their positions, while many were replaced with Houthi loyalists or tribal figures close to the movement. Replicating a divide-and-rule strategy used in other governorates under their authority, the Houthis thus attempted to weaken local structures of power splitting up tribal or family lineages and manipulating local tribal orders through the appointment of second-rate shaykhs in state positions.

Some examples may further clarify these dynamics. The Houthis designated Abdulhamid ash-Shahiri, brother of Abdulkarim, as First Deputy Governor with authority over the north-east of the governorate, and Muhammad ash-Shami, a Hashemite from Ibb, as Security Director. Through these two appointments, the Houthis managed to break up an influential tribal group and assert control over the governorate’s north-eastern districts, while handing over local security to the member of a prominent Hashemite family with close links to the Houthis’ inner circle. Additionally, the Houthis’ general supervisor in Ibb, at-Tawwus, soon established contacts with the members of the Tribal Mediation Committee. Among them are Abdulwahid Salah, appointed by the Houthis Governor of Ibb in August 2015; Aqil Fadhil who later became the GPC’s local leader; Ashraf al-Mutawakkil, a Hashemite appointed deputy governor in August 2016; Ibrahim al-Musawi, another Hashemite who became director of the Youth and Sport Office; and Tariq al-Mufti, a Hashemite who was appointed member of the Shura Council in April 2018.

An Unstable Coalition and the Onset of Infighting

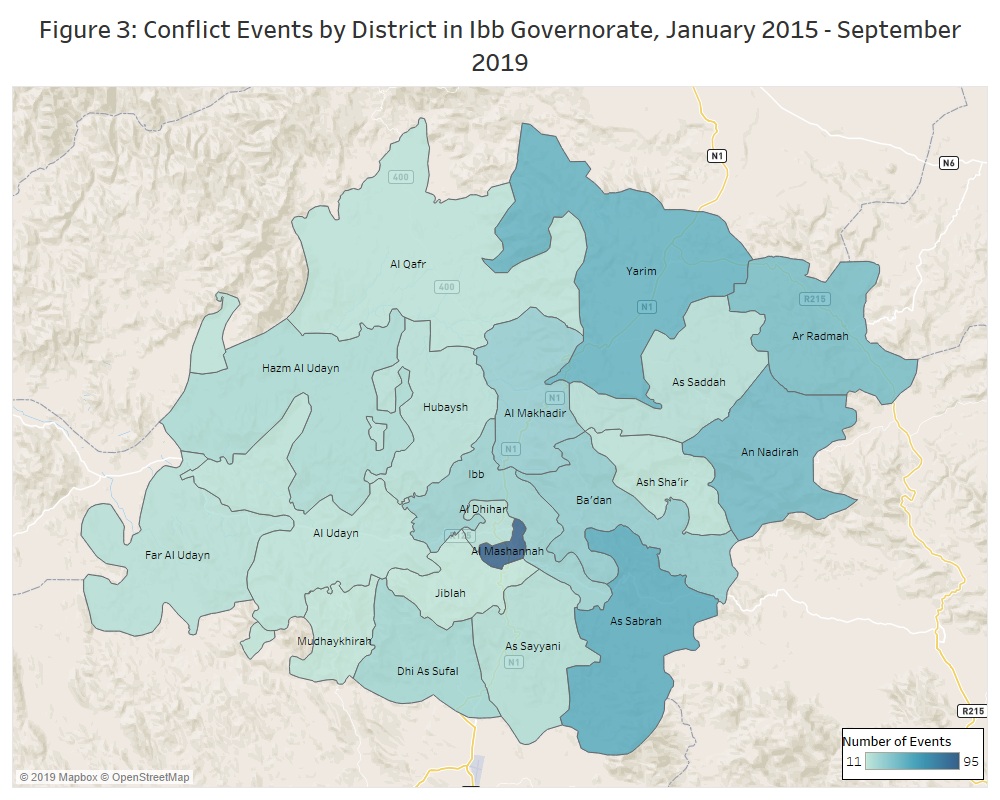

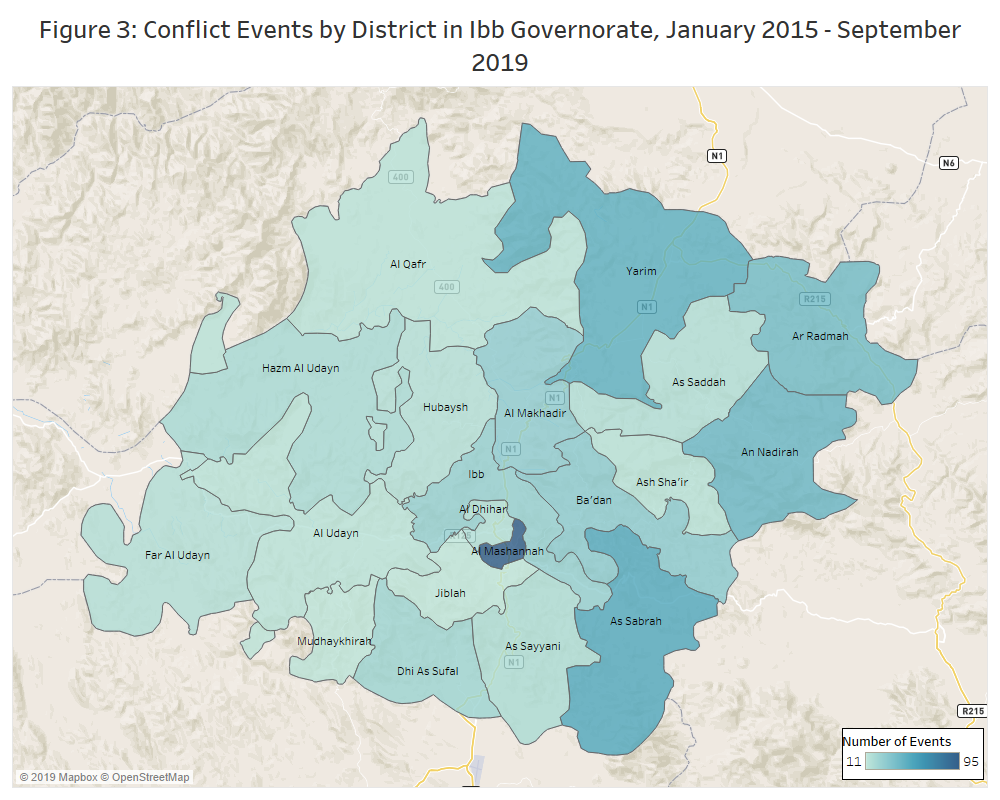

Unlike the neighboring governorates of al-Bayda, Taizz and ad-Dali, Ibb is not located on the front line of the war but has nevertheless experienced sustained levels of violence since the start of the conflict around Ibb city and in its easternmost districts bordering Ad Dali and Taizz (see Figure 3). Airstrikes are the primary mode of violence, followed by clashes between armed groups and improvised explosive devices (IED) attacks targeting both combatants and civilians.

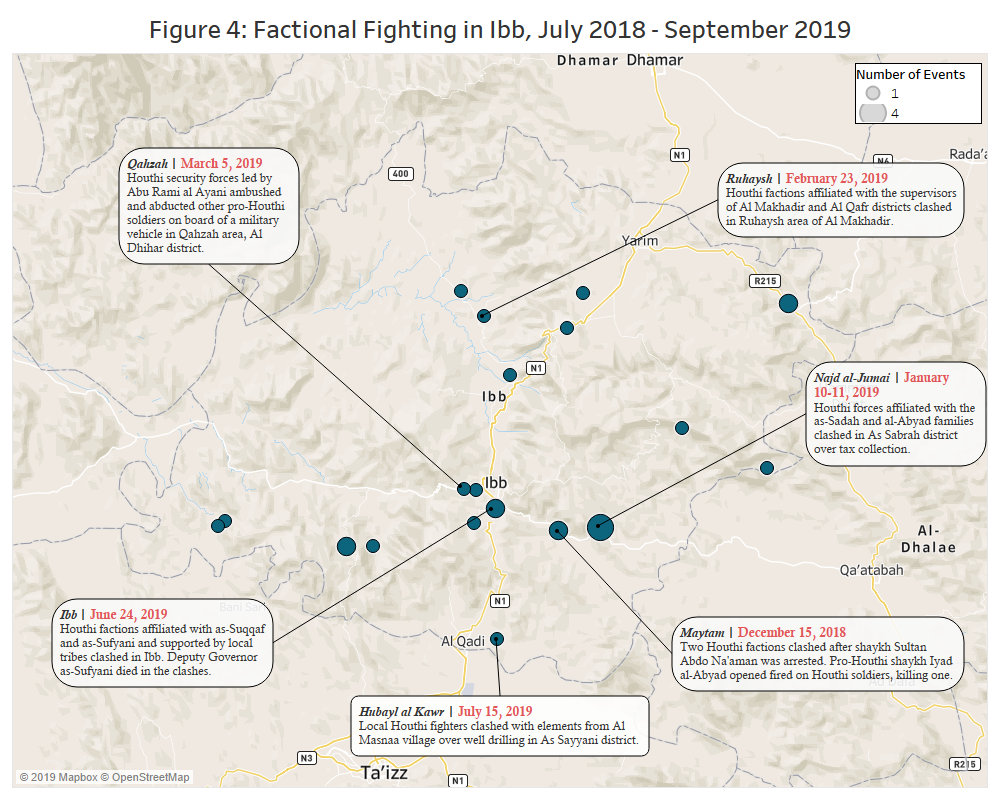

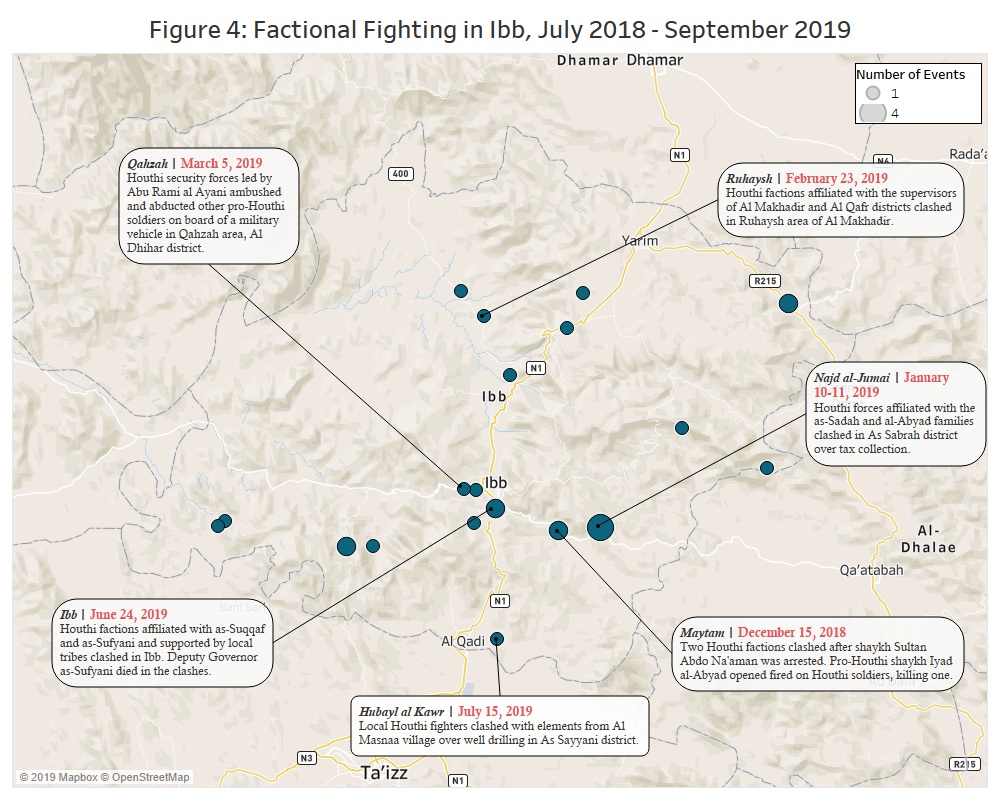

Factional clashes within the Houthi-Saleh alliance occurred occasionally between 2015 and 2017, often pitting Houthi militias against Republican Guard soldiers for the control of security checkpoints and tax collection. In the wake of Saleh’s assassination, infighting remained low, only to re-emerge vehemently in the second half of 2018. This wave of factional fighting is linked to changes in the local political order enforced by the Houthis.

In July 2018, Yahya al-Houthi – Education Minister in the Sana’a-based government and a leading political figure in the movement – reportedly visited Ibb to address urgent security issues. At the same time, Hamud al-Harithi was appointed Commander of the Rescue Police while Abdulhafiz as-Suqqaf – the former Deputy Minister of Interior, hailing from Ibb – replaced Muhammad ash-Shami as Security Director in the governorate (Yemen Shabab, 26 July 2018). Yet, there was no surge in violence during the January-August period of 2018 to justify the reshuffle in response to alleged ‘security emergency’.

In September 2018, new reshuffles involved the local military and security leadership. Abu Ali al-Ayani, the Houthis’ military supervisor, was appointed commander of the Ibb axis and of the 55th brigade; Yahya Muda‘is, the Houthis’ security supervisor, was appointed Chief of Staff in the Central Security Forces; Abu Hashim adh-Dhahyani was appointed director of the Political Security (al-Mashad al-Yemeni, 12 September 2019). In a further attempt to tighten the grip of Saada loyalists over the governorate, in October the Houthis appointed the new General Supervisor from Saada, Salih Hajib, as Deputy Governor for Security Affairs. Far from constituting routine reshuffles, these latest changes resulted in ousting local elites from key military and security positions in the governorate and instead elevating Houthi loyalists from Saada, with the only exception being Abdulhafiz as-Suqqaf.

These changes are reflected in the governorate’s precarious security situation, which has since plunged into growing instability. Starting from September-October 2018, the governorate experienced a spike in violence against civilians and in communal clashes, largely motivated by conflicts over land involving Houthi militias linked to local groups. Infighting began to surface in March 2019, when Houthi factions loyal to as-Suqqaf clashed with those loyal to Abu Ali al-Ayani.

Eventually, the political struggle over the security establishment merged with pre-existing tribal rivalries and precipitated into violent battles. In June 2019, the Babakar tribe, supported by as-Suqqaf, clashed with the Sufyan tribe, leading to the killing of the Deputy Governor of Ibb Ismail Abdulqadir as-Sufyani in the streets of Ibb city (al-Arabiya, 24 June 2019). These clashes involved units of security forces loyal to opposing military commanders, and show how the boundaries between the state and the non-state in Yemen are blurred. Abdulqadir as-Sufyani was an early Houthi loyalist: a Houthi representative in Ibb since 2011, he participated in the takeover of the capital Sana’a in September 2014, and later took part in fighting in the West Coast and in the Central Areas (Bawabatii, 26 June 2019). The Houthis reacted by removing as-Suqqaf from the Security Directorate and replacing him with the loyalist Abu Ali al-Ayani.

Infighting seems largely motivated by a rift between Ibb’s local elites and Houthi loyalists from Saada. After Saleh’s assassination in December 2017, the Houthis have accelerated the takeover of state institutions, replacing local supporters and GPC affiliates suspected of conspiration with militants close to the movement’s inner circle hailing from the northern highlands. This has led to an increasing overlap between formal state positions and political roles within the Houthi movement, triggering the reaction of local elites and tribal groups increasingly marginalized by the Houthis’ pervasive and exclusionary rule.

As the death toll now nears an estimated 100,000 fatalities since 2015, the conflict is increasingly embroiled in regional tensions which makes its resolution ever more difficult. Despite its international ramifications, the roots of the conflict continue to be predominantly domestic, and reflect national and subnational struggles for power and influence. In central and northern Yemen, local opposition to Houthi domination has resulted in multiple violent incidents involving local groups and former Houthi allies. These dynamics of co-option and control, however, are not unique to Ibb, but were instrumental in consolidating Houthi authority across other governorates such as Sana’a, Amran, al-Mahwit, Dhamar and western Marib.

While the Houthis have so far managed to tame the potentially dangerous repercussions of such events, they may struggle to enforce their rule should these pockets of resistance survive or activate. As the conflict stagnates and a military escalation is no longer imminent, keeping their home front united might prove the greatest challenge to Houthi rule in the future.