In the past ten years, the world has witnessed a decline in global cooperation and a severe downturn in security. This is manifest through several internationalized wars and massive humanitarian crises across the Middle and Near East, rising nationalism from significant global powers, transnational terror organizations using vicious violence and sophisticated recruitment techniques, cyber-attacks orchestrated by marginalized states, sustained levels of violence in nominally ‘post-conflict’ countries, and a drastic rise in both the number of non-state violent agents and repression by increasingly autocratic governments.

An intensification of violence and risk has accompanied these notable shifts. Three patterns summarize the directions and most prominent forms of violence in the coming years:

* Political violence is rising, and manifesting as disorder in multiple forms. Russia, Mexico and Turkey are key examples of how specific forms of political violence are growing in developed states. Presently, there are similarly high levels of political violence in Mexico and Syria[1]. Some estimates suggest that political violence results in more deaths than from within war environments.[2] We should expect political violence to continue, rather than wars to restart, and for government repression to increase.

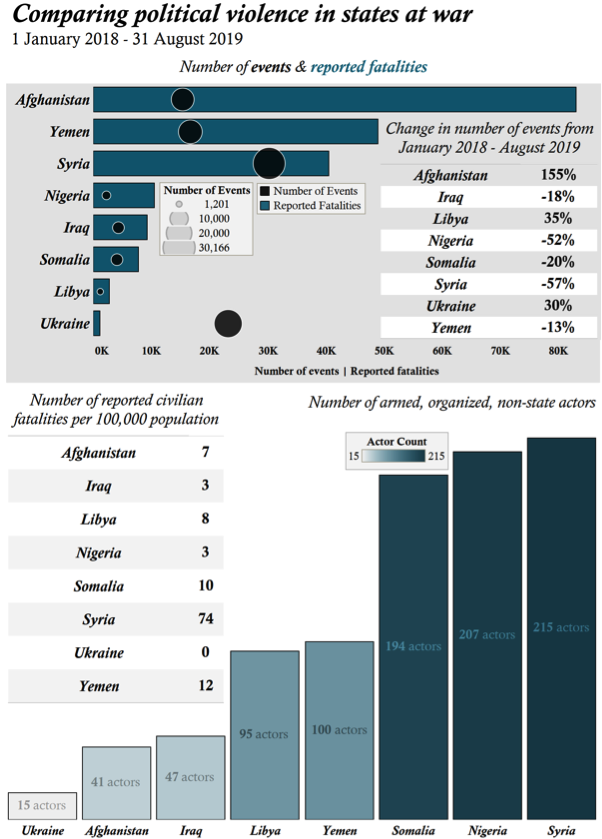

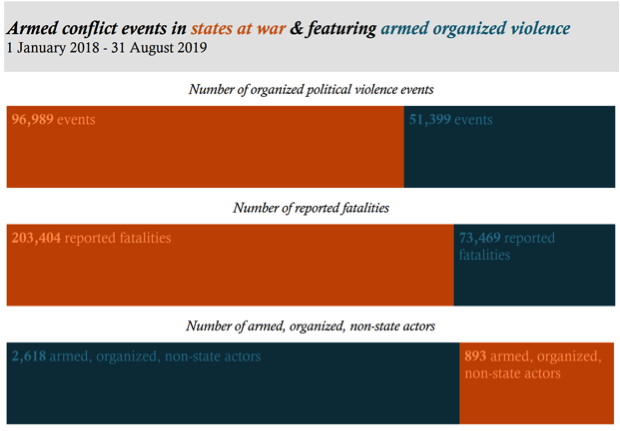

* Continued conflicts in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Somalia and Afghanistan demonstrate the intractable nature of wars in states with inconsistent government control and capacity across territory. Afghanistan’s war is the deadliest violent conflict currently being fought, with few signs that it will abate[3]. The Taliban is likely to establish almost full control over the state, which will decrease high levels of violence, but perpetuate gross human rights violations as a matter of government policy. This is not a context unique to Afghanistan. We should expect inertia in long-running conflict environments, which will be intermittently ‘resolved’ by local agreements of questionable duration and justice. In short, violence is an effective strategy for political power. Yet, of the eight states with current wars, the experience, level of violence and likely solutions are vastly different.

* The fallout from peacebuilding and stabilizing efforts, elections, and the intersection of crime and conflict has created an unprecedented rise in militia and gang violence. Rather than interpret these patterns as unleashed chaos, they have arisen due to the domestic politics of states and the economic benefits of conflict. But it stands that the form and intensity of conflict adapts to political competition within states. As a result, we should expect a continued rise in militia, ‘gang-like’ groups and violence, and for this to embed across almost all states.

Below are several notes on present trends and expected future patterns of political violence.

Disorder over wars

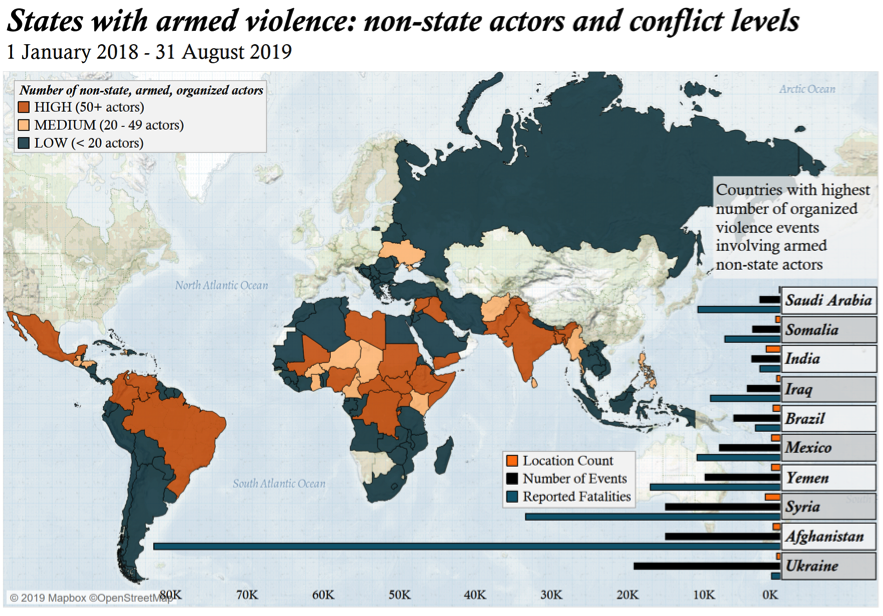

Violent political instability and disorder are widespread, multidimensional and adaptive. Disorder takes many forms: it looks like election violence; gangs that patrol cities offering security and services for a price; death squads that have ties to security forces; community vigilantes who operate identity-based security services; cyber-encouraged lone-wolf acts against communities; political assassinations and violence targeting political party supporters, journalists, migrants and ‘expendable’ citizens; and orchestrated campaigns of violence targeting women. Specifically, it results in conflicts like those in multiple centers across Philippines; continuing crises like those in Africa’s Great Lakes region; divided states in Libya, Yemen and Somalia; organized crime and violence in Central America; and politicized mob violence in India.

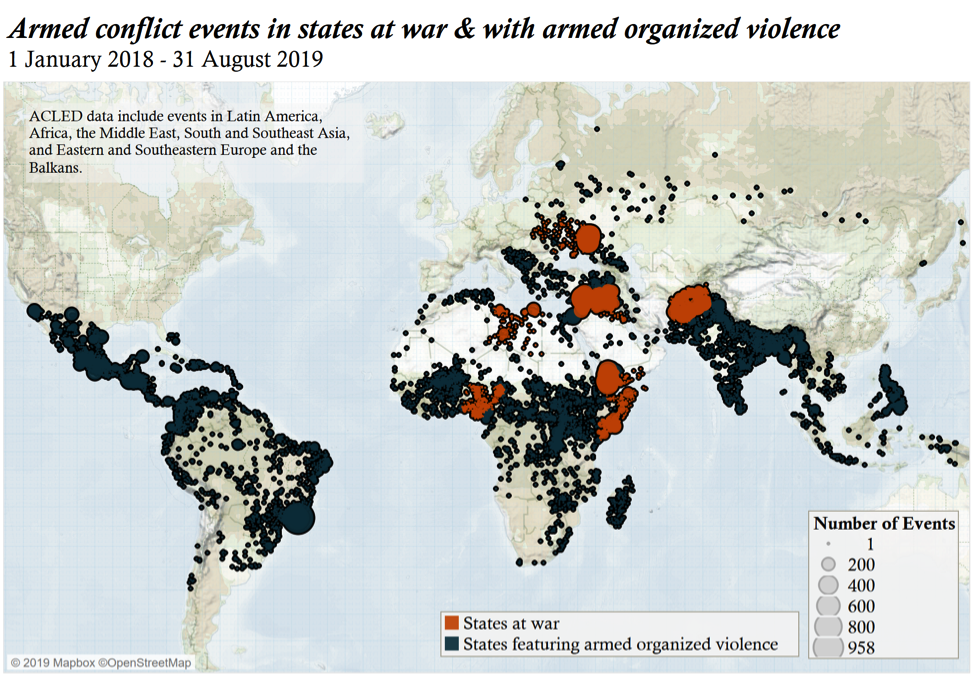

The lesson from this change in conflict is that political violence and disorder do not arise from breakdowns of political control, and they are not exampling of “exceptionalism”. As demonstrated by the map above, these are common, persistent, widespread forms of conflict. They arise and are shaped by local political and economic competition. In turn, we need to understand shifting power dimensions and corruption much more closely to follow this violence.

There is some form of violent, political disorder occurring in almost every state

Over the last 15 years, over half of the world’s population lives in direct contact, or proximity to, significant political violence[4]. We can no longer ask “which state has the riskiest drivers of violence?” because many states are sites of significant disorder. The ‘center of gravity’ for political violence is not sub-Saharan Africa where conflict levels have stayed relatively high and stable. The greatest rise in political violence in recent years has been in states within the ‘developed’ category including Syria, Brazil, Mexico, the Philippines, Ukraine, Libya and Egypt (see map above).

Modern political violence is no longer a scourge of low-income states; it is not a result of ‘state weakness’ or ‘fragility’: it can occur in states with a robust governing apparatus and economic growth. Middle-income country conflicts have similar aims as those in low-income states: to secure the control of the state, territory and rents in the hands of select political interests. It is a tool of control used by the most powerful, which has been exacerbated by state building efforts and an attempt to ‘recentralize’ power after two decades of decentralizing and liberalizing efforts. Further, economic growth and prospects have diverged as direct indicators or outcomes of conflict. Low-income states with significant, large-scale conflicts have failed to meet globally agreed development goals, or significantly advance towards those goals in the past decade. These bleak facts suggest that it is difficult, if not impossible, to ‘develop out’ of conflict.

The number of political militias and gangs has drastically increased

Much of the recent rise in violence and risk has come from political militias and gangs[5]. These groups manifest in a variety of ways: some are gangs, who adopt a political affiliation for specific jobs. Some operate as security/control providers on an ethnic, religious, or regional basis due to the provisional lack of security in modern developing states; others are ‘re-purposed’ and co-opted by political figures in periods of competition and external shocks to produce targeted violence against opponents[6]. Politicians hire groups to use in political competitions, but they also can operate for state security services as paramilitaries. These are not ‘warlords’: they are most often used at the behest of established political figures to compete politically with each other.

Others have explicit economic motives and control illicit trade, resource and migration routes. Cartels are an extreme example of a parallel system with political and security agendas to further an economic and financial outcome: it is organized crime with political outcomes. Cartels provide a warning of what might emerge in states with poor governance: their ability to exploit weaknesses in state security, co-opt government agents, destroy public security and space towards their ends is testament to what happens when some militias and gangs collectively organize. Consider two examples of their different influence: in Mexico, cartels create significant security vacuums and high levels of civilian harm; in Mali (2012), a perfect storm of extensive organized criminal networks, a serious national security crisis, and active transnational political groups looking for bases exacerbated the current Sahel crisis. As a result, 180 distinct militia groups are now operating across the Sahel[7]. When these types of groups do collectively organize, and can fund activities through a myriad of illegal ways, it leads to widespread violence and destruction. As the figure below demonstrates, across Africa, gangs and state forces account for the greatest increase in violent actors.

There is a violence market

Political violence is increasingly transactional rather than motivated by group grievances. There are strong economic parallels between labor markets and the violence market active in developing states. It is equally important to focus on the buyer of violence as well as the supplier of force. Previous discussions of gangs often concentrate on the supply of labor from growing, young, under-employed population, rather that the ‘work’ of militias and the buyers of violence. The demand for low level, intermittent conflict has increased, which in turn has increased the supply, and formalized the rules of engagement. This is not ‘chaos’, but the forms of exchange between gangs and politicians are increasingly cheap, transactional and shallow[8]. The result is a hierarchy of armed groups that is reflected in price, actions and motives. Rarely are these environments characterized by overarching organization and control, which increases the coordination and lethality of these groups.

Politicians hire gangs to engage in violence around elections, to kill and threaten competitors and their supporters, seize territory, secure illicit trading routes, and increase their political leverage through force (see recent violence in the Philippines with vigilante killings of government opponents; the 2015 election in Burundi which strongly featured the Imbonerakure militias, themselves recruited from ‘unemployed youth’ and hired by the regime’s CNDD party; or the extensive work on Sierra Leone ‘Cliques’ and their relationships to politicians). In addition, communities are often forced into protection rackets, ‘taxes’ for ‘security’, and other exchanges between gangs who can act with relative impunity within their ‘territory’ and with the protection of their possible ‘patrons’ (see recent patterns in Brazil[9])[10].

The market perspective strips political violence of its grievance ‘motivation’ and instead concentrates on exchange terms, and the ways selling groups can distinguish themselves within a crowded field of competitors. Violent ‘brands’ are ways that a group can do so: territorial, identity, religious, age, party, previous associations, costs, and modality of violence are each ways that groups compete for intermittent patronage[11]. The buyer decides the cause; the seller provides the conflict.

Political violence is not punished or disqualifying

Extensive networks of militias and gangs are organized by the market, and survive because of immunity and impunity to state and international justice. Politicians that regularly manipulate the political order, use violence for competition, and engage in financial corruption are often rewarded in appointments and favor. Control of the use of force, or ability to purchase force, are signals of primacy in a political environment. Violence is an effective tool of political competition.

Domestic impunity is paired with a chronic lack of accountability for gross human rights violations and violations of international humanitarian law. From the use of chemical weapons in Syria, to the invasion of the Ukraine, carpet bombing of Yemen by Saudi Arabia, and the attempted genocide in Myanmar, there are few existing ‘red lines’ that the international community is willing and capable to uphold when confronted with clear breaches by domestic or foreign agents.

International community actions that legitimate political elites and political settlements often reinforce the ‘benefits’ of violence. The overall costs of these violent strategies is to entrench and legitimize a narrow political elite, increasing their ‘political resilience’ at the cost of the social reliance of citizens. This is likely to continue as global cooperation declines.

State building increases some risks of violence against civilians

While the international community engages in extensive statebuilding and stabilization efforts, the security of states has not resulted in the security of people. Strong states use violence strategically to further entrench power; in weaker states, violence is perpetrated by many, equally powerful agents; increasingly autocratic states are populated with political elites who use violence to increase their leverage and challenge competitors. A focus on achieving stability through the inclusion of violent elites can reduce violence levels in the short term, but may increase violent competition incentives in the longer term (see recent reports on the Sudanese change of power and Colombia’s possible return to conflict in 2019). As seen below in a civilian risk index (with examples of cases in each category), there is a great range in how states and citizens experience the security environment: in places like Mexico and Burundi, active and latent groups dominate the security environment, while in Iran, Turkey and Ukraine, the level of per capita civilian killing is low, but perpetrated by the same small range of groups. In countries like Ethiopia and Pakistan, the possibility of high numbers of ‘re-activated’ groups mean that civilians are at a heightened risk of mass violence, should the political environment change suddenly.

Conflict and peace tend to coexist in different degrees of intensity in many countries in the world, even after the formal end of a conflict. Living within a conflict affected country does not mean that every community is directly affected by the same form of violence: there is tremendous subnational variation in conflict dynamics which are direct responses to local political conditions. Further, multiple forms of conflict can occur simultaneously. In short, states and regimes remain uneven and biased in securing citizens and territory; they are not neutral in how conflict manifests. Attempts at recentralizing power amongst a growing elite circle has created difficult and risky contexts for citizens.

Prediction, measurement and containment[12]

A pressing question is whether we are caught up in short term, limited scrambles for power amongst a large number of local groups, or whether this is a prelude to a longer-term competition across small and larger powers, proxy wars and extensive instability. This report is to serve as a diagnosis of the changes currently at play. It suggests that ignoring the new realities of conflict, or relying on previous corrections, will fail to contain and abate this disorder.

If short term scrambles, successful political settlements may decrease violence, but at the cost of reinforcing the ‘benefits’ of conflict to the powerful. This can lead to cycles of violence and limited political development. These short term scrambles are often calculated and strategically aligned attempts to claim positions, voters, rents and territories. A significant problem will emerge if regimes, elites and militias see violence as the most successful way to compete.

In longer term competitions, the protracted use of violence is less possible to mitigate, as it is perpetrated by many interests who do not prioritize domestic stability or civilian safety. There is few incentives for peace in these environments without international support and cooperation.

Because peace does not necessarily follow conflict, and there exist so many varieties of, markets for, and benefits of political violence, a reasoned prediction for the future is difficult[13]. More groups make violence less predictable, in part because most active groups have vastly different goals and behavior, organizational potential, financial incentives and prospects. Yet, the benefits of violence as a political and economic tool are clearly demonstrated in disorder. While political motives are clearly linked to group formation, economic incentives allow for continuation and adaptation. Expanding our interpretation of how funding and financial opportunities heighten violence, and assessing how security environments have evolved, is a first step. A second step will be to grapple with how the fallout from two decades of intervention, stabilization, liberalization and decentralization of power has created the opportunities for these forms of violence to proliferate. A central theme to these forms of violence is that they are adaptations to the local political environment: these environments must incentivize lower violence through reliable alternatives for employment and competition, and sanction those who use and buy it by denying them access to office, rents, territory, and impunity.

____

Notes:

[1] This is an assessment based on events by armed, organized agents, rather than fatalities, and is relevant for the present period of 2019 (as the Syrian war declines)

[2] This is not the case when a full assessment of the deaths in Yemen, Afghanistan and Syria are accounted for

[3] Assessed as such if judged by number of fatalities: Afghanistan is the most fatal of wars. If judged by events, at mid-year, Yemen registered about the same number of events as Afghanistan, and Syria registered several thousand more: https://acleddata.com/2019/08/02/mid-year-update-ten-conflicts-to-worry-about-in-2019/)

[4] This is assessed by the active presence of more than one armed, organized non-state, politically motivated violent groups

[5] See: Pragmatic and Promiscuous: Explaining the Rise of Competitive Political Militias across Africa: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0022002714540472

[6] Examples of these groups are depressingly common: the Janjaweed in Sudan; Sunni Tehreek in Pakistan; ZANU-PF militias of Zimbabwe; Kikuyu militias in Kenya; Fulani in Nigeria; the Awami League in Bangladesh; and Myanmar’s National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA)

[7] https://www.acleddata.com/2019/03/28/press-release-political-violence-skyrockets-in-the-sahel-according-to-latest-acled-data/

https://www.acleddata.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/ACLED_TenConflicts2019_MidYearUpdate_8.2019.pdf

[8] http://matsutas.com/big-men/the-making-of-a-market-politicizing-gangs-in-sierra-leone-by-kars-de-bruijne/ . See also recent work by De Waal (2016)

[9] https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/brazils-violence-map-shows-alarming-trends

[10] A market system co-exists with a more formal ‘patrimonial’ system of politicians with associated militias; and there is evidence of both state and non-state organizations hiring and disseminating this ‘hired labor’.

[11] Dowd, Caitriona (2016) The emergence of violent Islamist groups: branding, scale and the conflict marketplace in sub-Saharan Africa.

[12] This piece is strongly out of sync with recent discussions around SDG 16.1. Deaths are one way to assess political violence, and while SDG16 means to decrease deaths, fatalities and violence risk are not the same. Deaths can be highly correlated with violence (e.g. Yemen)

[13] Prediction efforts often use patterns from the past 50 years to suggest the general future direction. We suggest that post WWII and post-Cold War patterns present something of an aberration, and more recent patterns (post 2010) present more reliable ‘prior’ violence patterns. Prediction also strongly depends on data choice, and if data does not pick up smaller group actions, or local patterns, it is insufficient to explain a drastic rise in these very outcomes.