Turkey’s recent assault in northeastern Syria, which follows months of regime consolidation in the northwest, has the potential to even further advance regime gains across Syria. In the third quarter of 2019, the Syrian regime and its allies finally made substantial territorial gains against rebel and Islamist groups in northern Hama and southern Idleb provinces in Syria’s northwest. By capturing key sub-districts (nahiya) like Madiq Castle, Kafr Zeita, Khan Shaykun and others (see ACLED’s most recent ‘State of Syria’ map), the regime inched closer to its goal of opening the M5 international highway, which stretches across the length of northwestern Syria into Turkey. These regime advances were quickly followed by the rapid Turkish assault in northeastern Syria. This assault has opened a new front in the conflict that may endanger the tenuous ceasefire between regime and rebel forces in Idleb province, administered with Turkey and Russia as guarantors, and provides the regime opportunities for further advances.

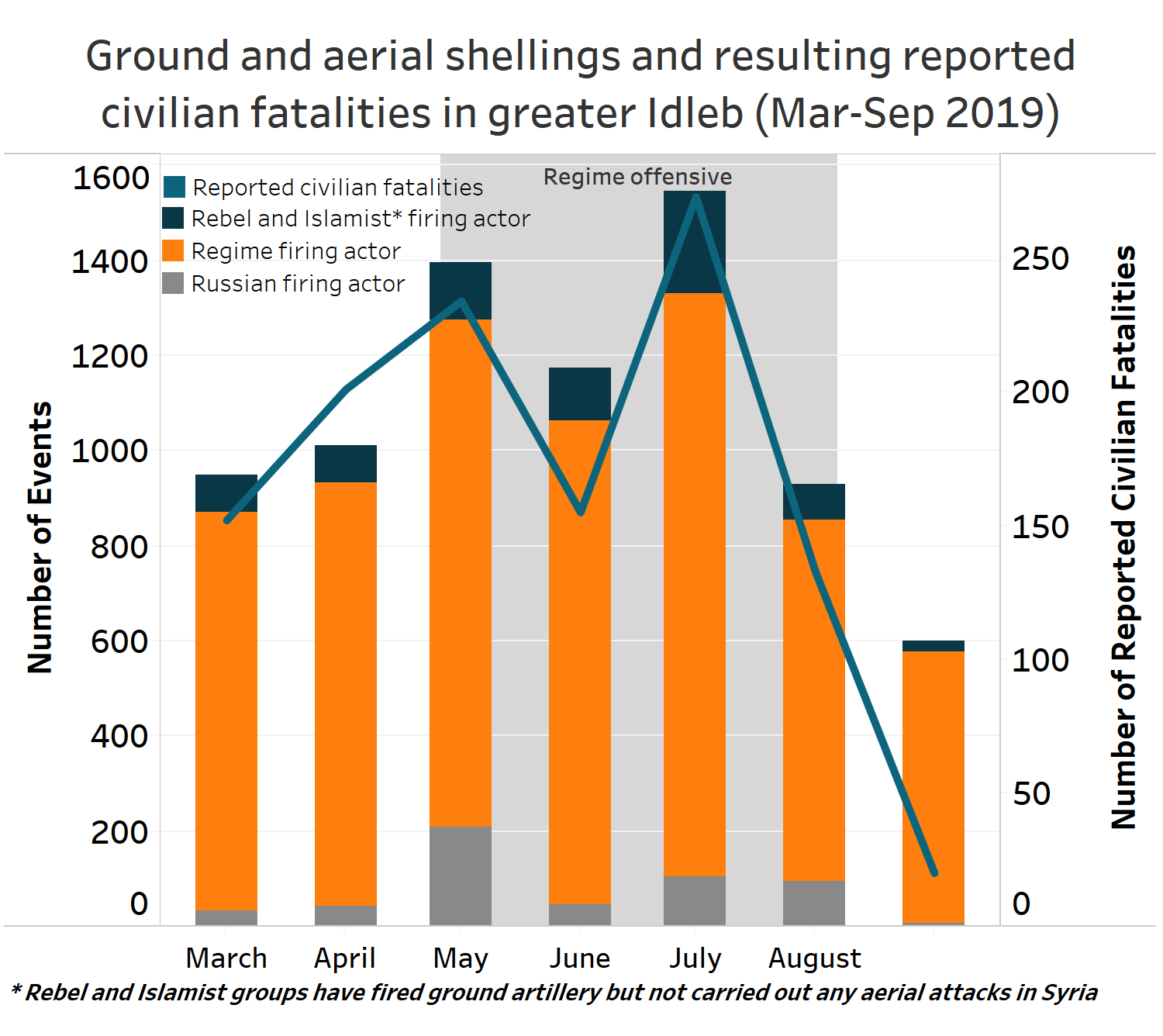

The Assad regime has long prioritized regaining territory along the M5, which connects Damascus in the South and Aleppo in the north (Reuters, 6 May 2019). The reopening of the M5 would provide a vital lifeline to the Assad regime’s economy, which has withered under eight years of war. In parallel, the retaking of the Kabani area and the surrounding Hama countryside would secure regime-allied Russia’s base in Hmeimeim in northwestern Syria from rebel and Islamist drone attacks, which have increased in frequency in recent months (Asharq Al-Wasat, 29 April 2019). This consolidation requires the regime to retake all of Hama and much of Idleb provinces, as well as the neighboring Kabani area in northeastern Lattakia province. As these recent advances only came after years of sustained aerial and ground bombardments, continued consolidation is not an easy task. As such — and given the regime’s stated goal of retaking all Syrian territory, and the unstated and more strategic goal of reopening the M5 highway — the Idleb ceasefire was never going to be a long-term line of demarcation. Violations of the ceasefire have been abundant, with most being committed by state and allied forces (see graph below). Turkey was held responsible for ensuring rebel and Islamist compliance of the deal. This is despite the fact that Russia appeared to do little to throttle Assad’s forces’ harassment across the ceasefire line. On the contrary, Russia also seeks to retake Idleb province — as much to secure Assad as to secure its own interests in the country — although through a more moderate strategy.

For Turkey, the territorial advances made by the regime in the third quarter of this year are likely to have spurred it to accelerate its demands to the United States for their withdrawal to facilitate a security zone in northeastern Syria. Turkey demanded a security zone to insulate it from attacks by the Syrian Kurdish YPG (People’s Protection Units) group, who it accuses of being synonymous with the Turkish Kurdish PKK (Kurdish Workers Party), with whom it has fought a decades-long insurgency. In addition, Turkey is seeking a security zone as a place to facilitate the return of Syrian refugees living in Turkey. This sustained pressure finally bore fruit in a phone call on 6 October, between Presidents Erdogan and Trump, in which the latter finally agreed to remove American military forces from northeastern border areas (Washington Post, 8 October 2019). After having been reactive to events in northwestern Syria, Turkey was then able to retake the initiative and try to adjust the balance of power in Syria more in its favor by gaining territory it could use as leverage against the Assad regime.

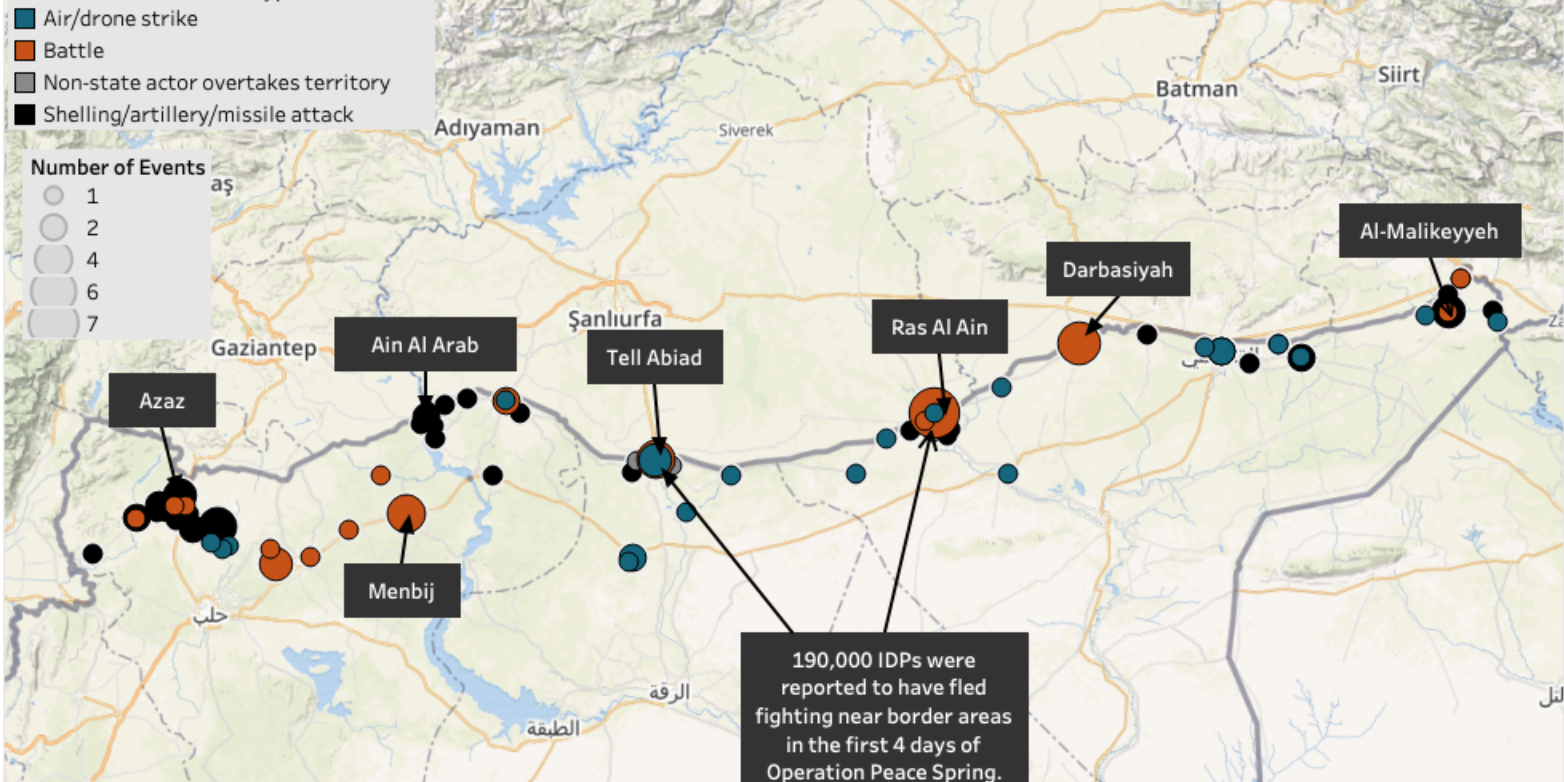

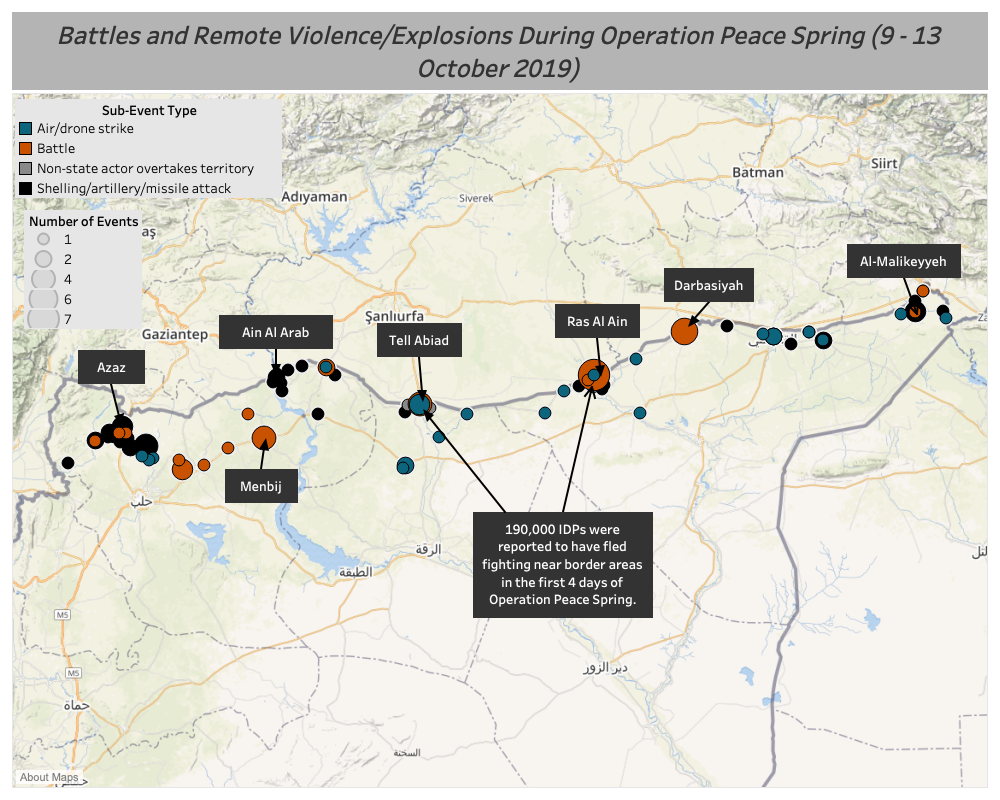

So far, Turkish forces and their allies have moved rapidly, and their quick success demonstrates that the operation was well planned and, so far, well executed. Operation Peace Spring — the name given to the Turkish army and Syrian National Army advance into Raqqa and Al-Hasakeh provinces — forces have pushed into Syria along several axes into Tell Abiad in Raqqa and Ras al Ain in Al-Hasakeh in the country’s northeast. By the 13th of October, Tell Abiad had been captured by Turkish and local allies after swiftly capturing the surrounding villages (see map below). In addition, Operation Peace Spring moved quickly into the Nusf Tall area in Raqqa province and captured part of the M4 international highway, effectively cutting YPG/QSD (Syrian Democratic Forces)-controlled northeastern Syria into two. Without access to the M4, YPG and QSD forces are now unable to move personnel and equipment between Raqqa and Al-Hasakeh provinces. Turkish and allied forces are also moving towards Ain Al Arab (Kobani) and Menbij in northern Aleppo province, although these areas are closer to regime-held territory. As such, their ownership is likely to be subject to an agreement between Turkey and the Syrian state, as mediated by Russia. Indeed, an agreement has already been inked for the regime to take control of areas surrounding Menbij and Tabqa airbase in exchange for protection (Al Jazeera, 15 October 2019).

In these newly acquired territories, Turkey and its local Syrian allies are likely to become bogged down in a guerilla war with QSD and YPG sleeper cells as they have seen in Afrin and Azaz areas in northern Aleppo province. Assad and Russia, on the other hand, are likely undeterred in their goal of opening the M5 highway, securing Hmeimem airbase, and ultimately retaking the whole country. Indeed, regime and Russian ground shelling and airstrikes have continued after the most recent territorial acquisitions. As Turkey will remain focused on fighting in the northeast of the country, Assad and Russia may take the opportunity to push further into Idleb province. If and when this does happen, Syrian refugees, as well as rebel and Islamist groups, will likely have few options: either return to the vengeful bosom of the regime or pursue uncertain exile elsewhere. Just as civilian fatalities spiked during this most recent round of fighting (see graph above), they are almost certain to continue to rise.