In Yemen, more than five years of conflict have contributed to an extreme fragmentation of central power and authority and have eroded local political orders. Local structures of authority have emerged, along with a plethora of para-state agents and militias at the behest of local elites and international patrons. According to the UN Panel of Experts, despite the disappearance of central authority, “Yemen, as a State, has all but ceased to exist,” replaced by distinct statelets fighting against one another (UN Panel of Experts, 26 January 2018).

This is the third and final report of a three-part analysis series (ACLED, 9 May 2019; ACLED, 31 May 2019) exploring the fragmentation of state authority in southern Yemen, where a secessionist body – the Southern Transitional Council (STC) – has established itself, not without contestation, as the “legitimate representative” of the southern people (Southern Transitional Council, 7 December 2018). Since its emergence in 2017, the STC has evolved into a state-like entity with an executive body (the Leadership Council), a legislature (the Southern National Assembly), and armed forces, although the latter are under the virtual command structure of the Interior Ministry in the internationally-recognized government of President Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi. Investigating conflict dynamics in seven southern governorates, these reports seek to highlight how southern Yemen is all but a monolithic unit, reflecting the divided loyalties and aspirations of its political communities.

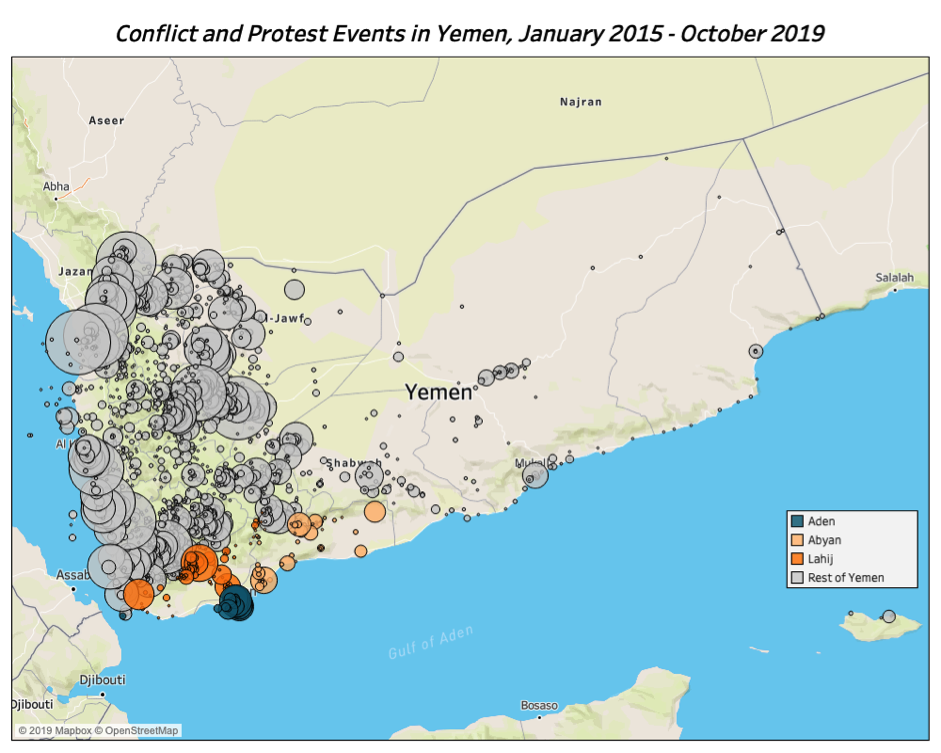

This third report focuses on the port city of Aden, a governorate in itself, and the neighboring Abyan and Lahij governorates. They are notorious for being the operating area of the primary military wing of the STC: the Security Belt forces (SBF). They have recently been at the center of tensions within the anti-Houthi front and the Saudi-led coalition, but have since 2015, the date where ACLED’s data collection for Yemen begins, experienced different dynamics. Aden, the interim capital of the internationally-recognized government of President Hadi, has notably had a very volatile political and security environment, leading to several outbursts of violence. Abyan and Lahij, despite the western and northern border fronts of Lahij, have encountered lower levels of violence, mostly driven by the fight against militant jihadi groups. Conflict and protest events in the three governorates within the wider Yemeni context are visualized in the introductory map below.

Aden

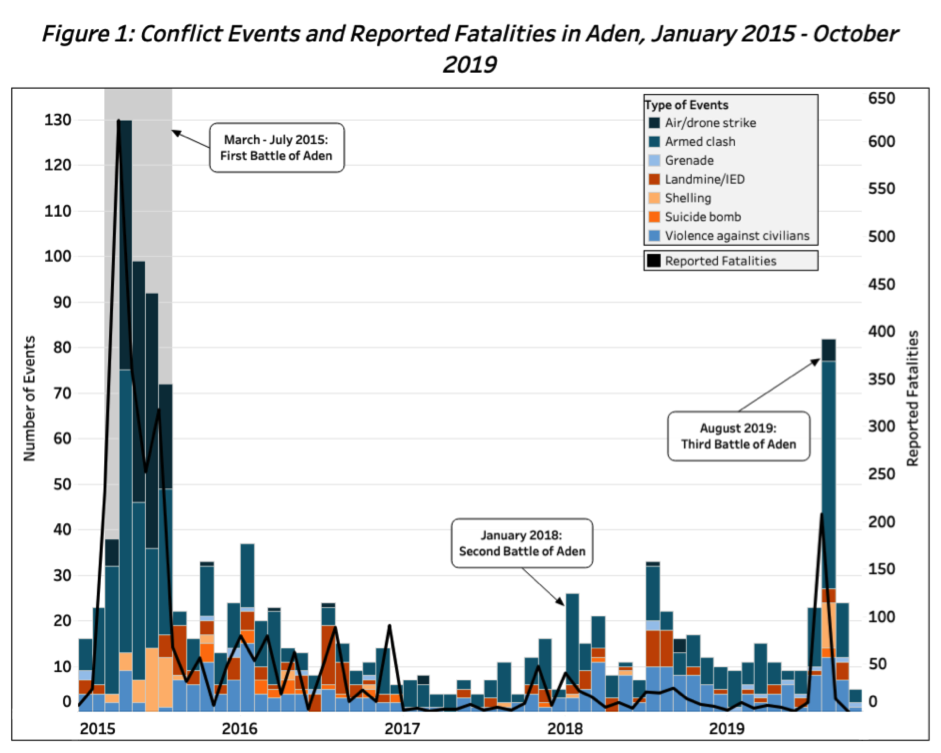

In early 2015, after President Hadi fled Sana’a following its fall to the Houthi-Saleh alliance, the southwestern port city of Aden became Yemen’s de facto capital. In March 2015, only a month after Hadi found refuge in the city, the new Yemeni capital became embroiled in conflict when Houthi-Saleh forces attempted a takeover, sparking one of the most violent episodes of the Yemeni war. This also marked a turning point in the conflict by triggering the Saudi-led air campaign (The National, 26 March 2015; France 24, 26 March 2015). In what can be referred to as the ‘first battle of Aden’ since 2014, ACLED records an estimated 1,783 fatalities over the five months of conflict. This forced Hadi to flee once again, finding refuge in Saudi Arabia (Reuters, 26 March 2015) where he has since spent most of his time. Figure 1 below shows that this has been, by far, the most violent episode in Aden since ACLED started recording data.

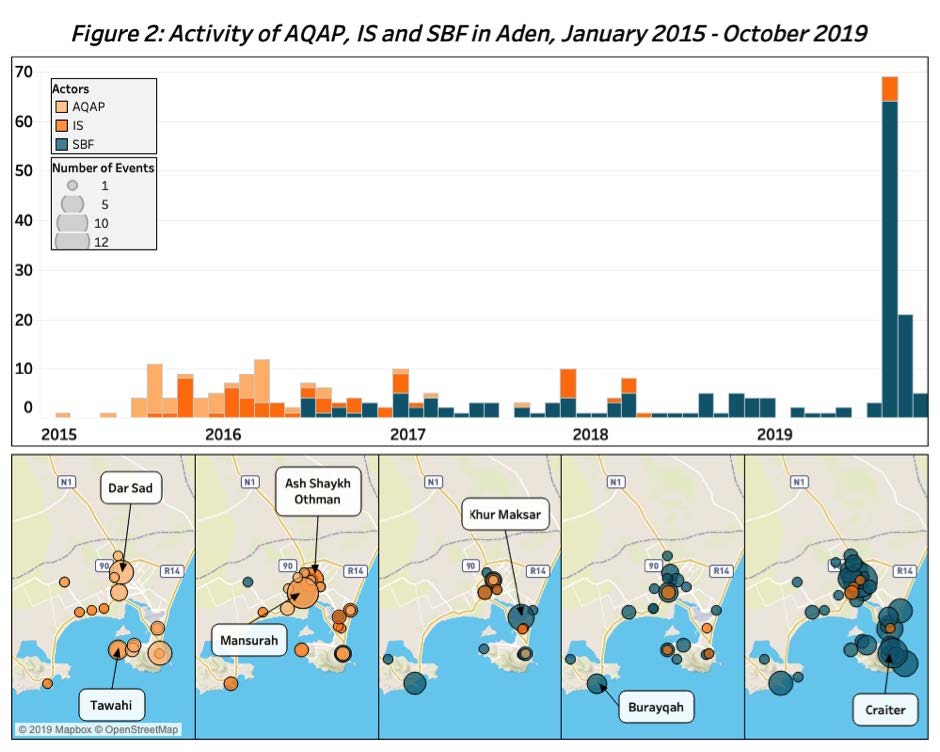

After Houthi-Saleh forces were ousted from the city in late July and the dust of the battle settled, an extremely fragmented security architecture emerged as a network of war-trained militias came to operate relatively freely alongside official Hadi government forces (ACLED, 7 December 2018). As depicted by Figure 2 below, the subsequent precarious security environment was rapidly exploited by jihadi militants of Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and the Islamic State (IS), which operated mostly in Mansurah and Ash Shaykh Othman districts. Reflecting the security deterioration, ACLED records 22 suicide bombings between October 2015 and December 2016 in orange in Figure 1 above (17 by IS and one by AQAP, with four perpetrated by unidentified armed groups), before a sharp decline of militant activity from 2017 onwards.

Figure 2 also seems to suggest that this decline in AQAP and IS activity is correlated with the emergence of UAE-backed SBF in the city. Part of a wider regional strategy (ACLED, 10 October 2018), Abu Dhabi rapidly invested in Aden after the ousting of Houthi-Saleh forces. In addition to starting the construction of a military base in Burayqah district west of Al-Sha’b area as early as in July 2015 (Amnesty International, 12 July 2018), the UAE trained, funded, and equipped several non-state actors that had proved crucial for the defeat of Houthi-Saleh forces. UAE-backed SBF quickly emerged as one of the main actors of the post-2015 security environment of the interim Yemeni capital.

SBF were formally established in Aden in March 2016, although a significant component of both combatant and leadership figures stems not from Aden but from the governorates of Ad-Dali and Lahij. Under the leadership of Brigadier General Wadhah Umar Abdulaziz and Colonel Nabil Al-Mashwashi, SBF fought common and organized crime alongside their primary counter-terrorism mission (UN Panel of Experts, 25 January 2019). As such, they likely played a significant role in reducing the number of conflict events in Aden that can be seen in Figure 1 above.

On the other hand, SBF have also been accused of systemic human rights violations (Human Rights Watch, 22 June 2017), and have arguably contributed to heightening tensions in Aden. Although they officially fall under the authority of the Hadi Ministry of Interior, they have in reality largely operated outside of official command and control structures, sometimes answering directly to Emirati orders (UN Panel of Experts, 26 January 2018). When the UAE-backed STC was established by sacked Aden governor Aidarus Al-Zubaidi and southern state minister Hani bin Braik through the May 2017 ‘Aden Historic Declaration’ (Southern Transitional Council, 4 May 2017), SBF became the armed wing of this new political body advocating for the secession of southern Yemen.

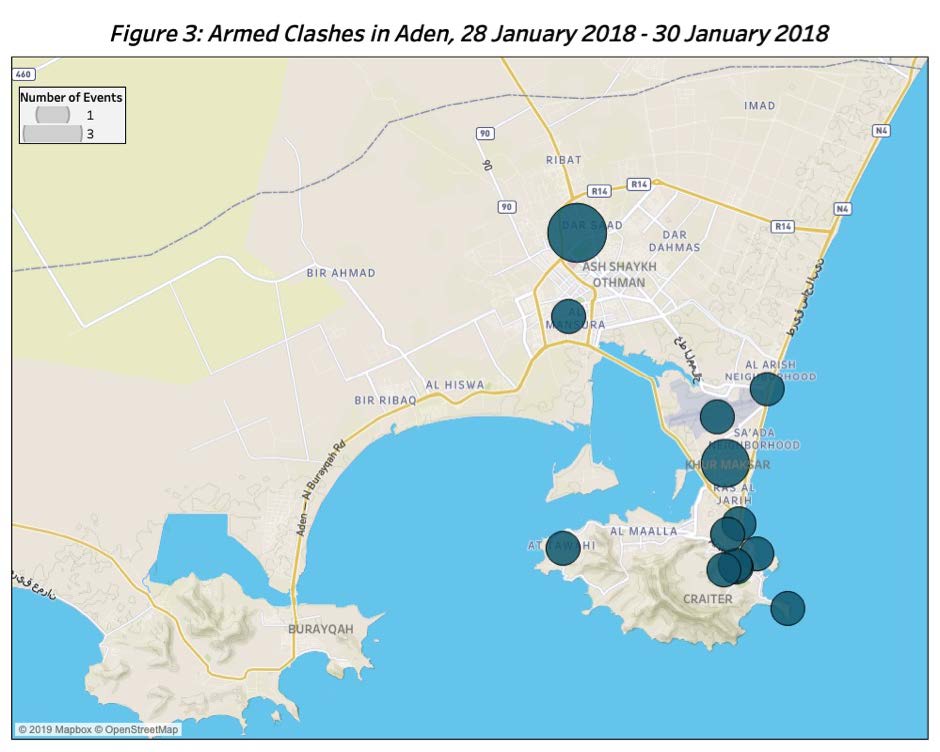

Despite sporadic clashes ACLED records between the UAE-backed secessionist camp and the Saudi-backed unity camp of President Hadi throughout 2017, the level of political violence remained low. The period from August 2016 to December 2017 was in fact the least violent period the city encountered in the past five years (see Figure 1). In January 2018, however, SBF took control of most of the city in only a matter of days following clashes that can be referred to as the ‘second battle of Aden’ (ACLED, 16 February 2018). As shown in Figure 3 below, ACLED records clashes in all districts but the western Burayqah district, a stronghold for UAE-backed forces in Aden.

Mediation efforts from the Saudi-led coalition allowed for a retreat of SBF (Reuters, 31 January 2018) and ushered in a period of relative detente between the two parties. As underlying issues remained unresolved, however, renewed clashes erupted in August 2019. On 1 August, a Houthi strike upset the overall security architecture of the city by killing more than 30 people during a military parade in Al-Jaala camp of Burayqah district, among which notorious SBF commander Brigadier General Munir ‘Abu Al-Yamama’ Al-Mashali (Al-Wahdah News, 1 August 2019; Ababiil, 1 August 2019).

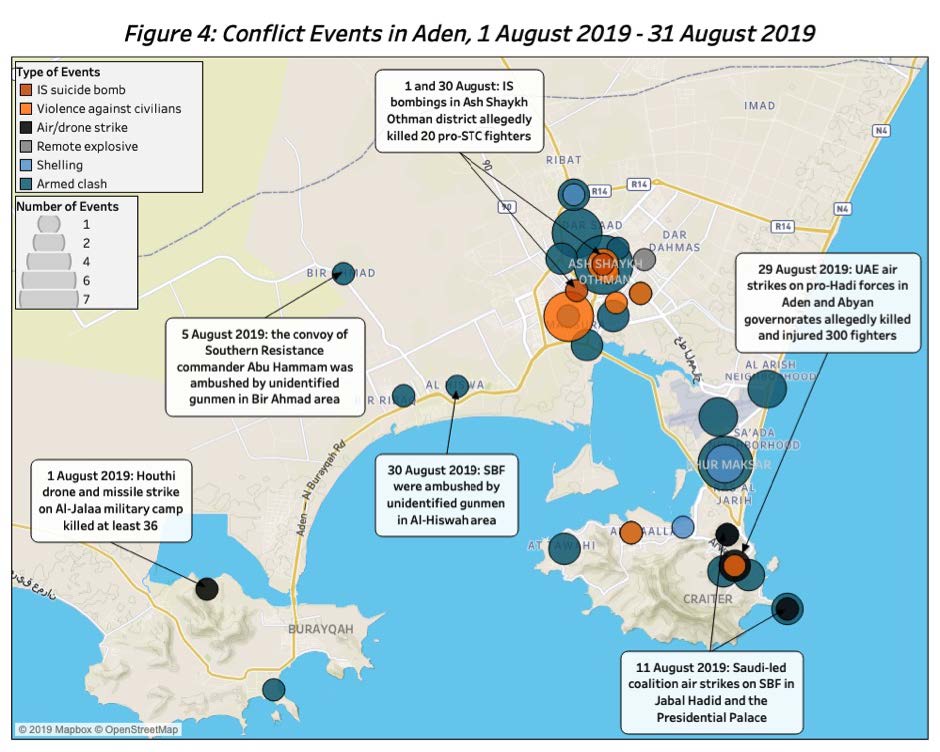

Fighting between pro-Hadi unity and UAE-backed secessionist forces rapidly erupted. This came after STC figures accused pro-Hadi forces affiliated with the Islah party of colluding against Southern forces with the Houthis (Ababiil, 3 August 2019). They intensified a few days later when Presidential Guards reportedly killed civilians attending the funeral of the Houthi strike’s victims in front of the Presidential Palace in Craiter district (Al-Mandeb News, 7 August 2018). As depicted in Figure 4 below, fighting spread throughout the entire city, including Burayqah, where SBF were ambushed in their stronghold in two instances.

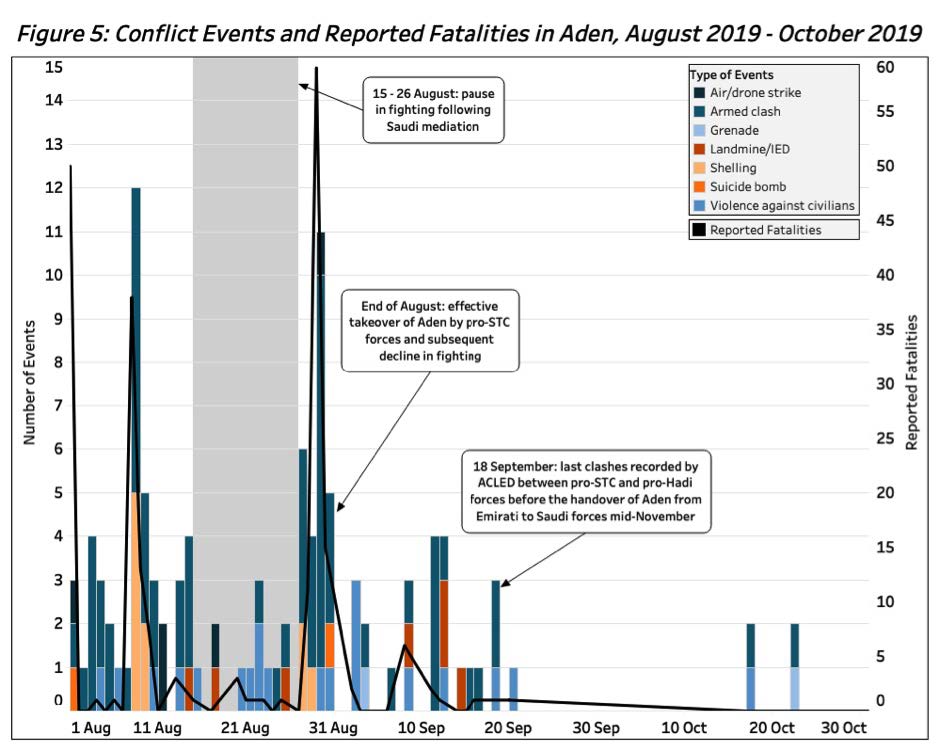

In mid-August, a lull was observed in the fighting following a new Saudi deployment in the city and agreements about the withdrawal of SBF from government and military institutions (Akhbarak, 15 August 2019). Fighting briefly resumed at the end of the month, ultimately forcing pro-Hadi forces out of the city once again on 29 August and leaving SBF in charge (Reuters, 29 August 2019). As can be seen in Figure 1, this month-long episode, the ‘third battle of Aden’, represents the highest peak of violence recorded by ACLED, both in terms of the number of events and the estimated fatalities – 218 – since the fight against Houthi-Saleh forces in 2015. Figure 5 below depicts in more detail this episode and shows that the fighting has since subdued.

This decrease in violence is the result of Saudi-mediated talks held in Jeddah between the Hadi government and the STC, which led to the signing of the Riyadh Agreement on 5 November (Al-Masdar Online, 6 November 2019). With Abu Dhabi effectively “relinquishing its authority over its Yemeni proxies [in Aden]”, the deal ultimately gives Riyadh complete control over the security situation in Yemen’s interim capital (Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, 5 November 2019). Its ability to bridge differences between Hadi and STC-affiliated forces in a planned restructuration of the security architecture of the city will be crucial in determining future patterns of political violence in Aden. As indicated by a recent wave of killings (Huna Aden, 4 December 2019), however, tensions between the two camps remain high.

Abyan

Abyan governorate borders Aden to the east and is the home province of President Hadi. It is also the stronghold of the Zomra elite, based across both Bedouin Abyan and Shabwah governorates. It is also understood by some observers to be largely in support of the Hadi government (International Crisis Group, 30 August 2019; Salisbury, 27 March 2018). Despite this alignment, however, the fighting between pro-Hadi and pro-STC forces that erupted in Aden in August 2019 also manifested itself in Abyan, where SBF have similarly made significant territorial gains. In part, one can assume that this recent influence of SBF in the governorate is a direct result of the successes of their counter-terrorism operations, which have been conducted since the fall of 2016 and mainly target AQAP.

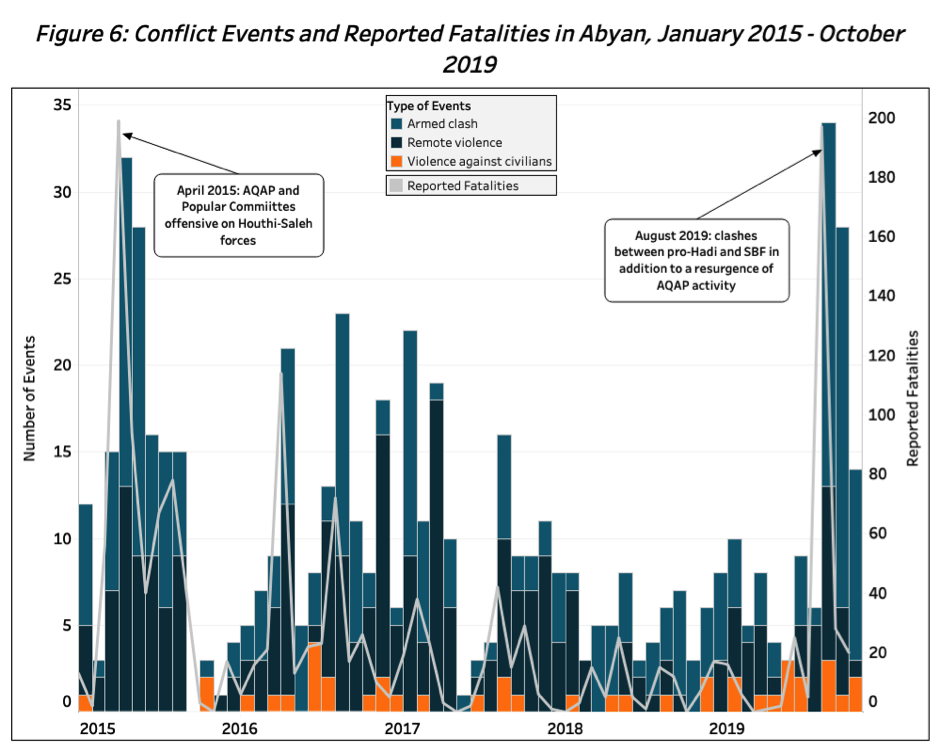

While the governorate has indeed harbored several Islamic jihadist movements since the 1980s (International Crisis Group, 2 February 2017), the activity of AQAP has seen a resurgence in recent years, at least in part as a result of the Houthi conflict. As the Houthi-Saleh alliance penetrated Abyan and captured its capital – the historical trading center and coastal city of Zinjibar – by the end of March 2015, pro-Hadi Popular Committees joined forces with AQAP militants during the following months. After peaks of violence and reported fatalities depicted in Figure 6 below, they managed to thwart this advance; by August 2015, pro-Hadi forces had regained control over Zinjibar (BBC, 9 August 2015).

Emboldened by this new military relevance, and as the conflict escalated in other governorates, AQAP, however, was able to exploit a new power vacuum and to take control of Zinjibar and Ja’ar cities in December 2015 (CNN, 2 December 2015). After the 2011 uprisings, Zinjibar and several other cities had already been captured by AQAP’s local branch, Ansar Al-Shariah. This was largely made possible because the organization offered efficient services, instruction and a functioning judicial system to a local population that lamented a lack of socioeconomic services from the state (International Crisis Group, 2 February 2017). In 2015, AQAP was once again able to take advantage of similar feelings of marginalization; over the 2015-2019 period, ACLED records a high number of protest events against the public administration in Abyan, especially in Zinjibar district.

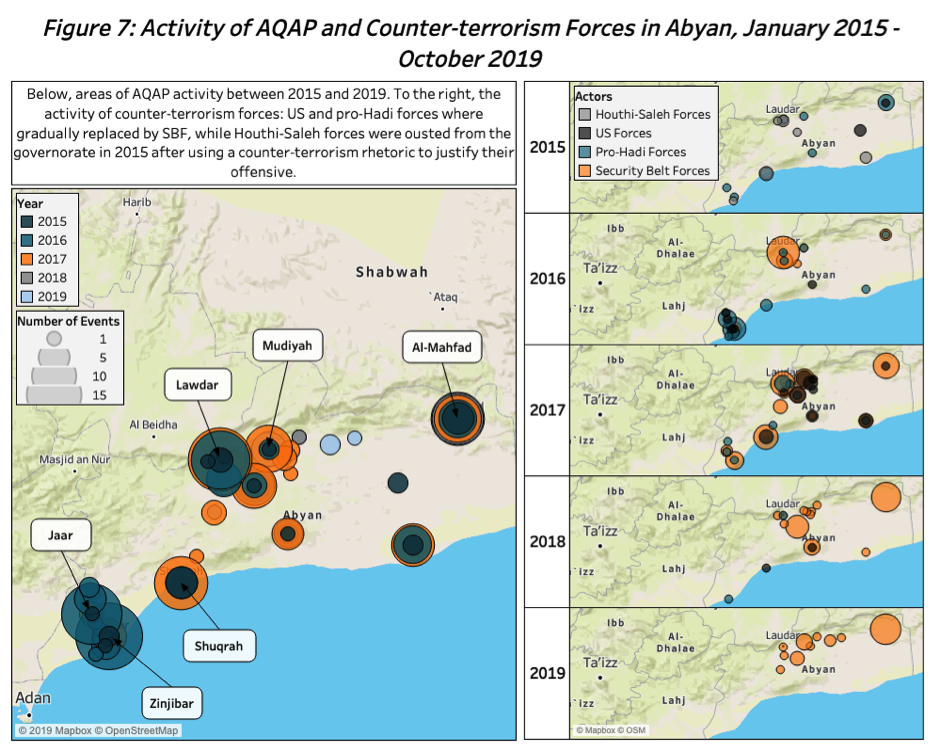

In August 2016, AQAP was nonetheless driven out of Abyan’s capital city by pro-Hadi forces (Stratfor, 14 August 2016). Figure 7 below, however, shows that its operations throughout the governorate did not resent this setback. On the contrary, AQAP activity in Abyan actually increased from 2016 to 2017 and spread to new areas as the organization was chased out of Zinjibar (in orange on the map of the left hand side of Figure 7 below). This trend only inverted in 2018, when most of AQAP activity migrated to the eastern district of Al-Mahfad. These developments seem to correlate with the activity of counter-terrorism forces, and, most notably, the rise of SBF in the governorate (see maps on the right hand side of Figure 7 below).

The uncanny alliance between pro-Hadi and AQAP forces against the Houthi-Saleh alliance in 2015 did not last. In 2016, the Hadi military, supported by US-led air strikes, carried out counter-terrorism operations against AQAP. In August 2016, Abu Dhabi also replicated the SBF of Aden and established a group in Abyan, nominally under Hadi control. By late 2016, around 2,500 SBF fighters were dedicated to countering AQAP activity in the governorate, under the leadership of Brigadier General Abdullah Al-Fadhli, a Salafi from Al-Wadi’a district also appointed security director of the governorate (Al-Omanaa, 27 November 2016).

Between February and September 2017, reports of activity by SBF completely ceased following the accidental killing of a civilian during an operation in Lawdar district and other setbacks in the area (Al-Mashhad Al-Janubi, 22 January 2017). Counter-terrorism operations, however, continued with an increase in US air strikes that reached a peak in March 2017. This is after President Trump declared Abyan an area of “active hostilities,” thereby relaxing US counter-terrorism rules of engagement (New York Times, 12 March 2017). As US air strikes decreased throughout the rest of 2017 and onwards, SBF concurrently increased their presence in the governorate, conducting the vast majority of counter-terrorism operations over the 2018-2019 period (see Figure 7 above).

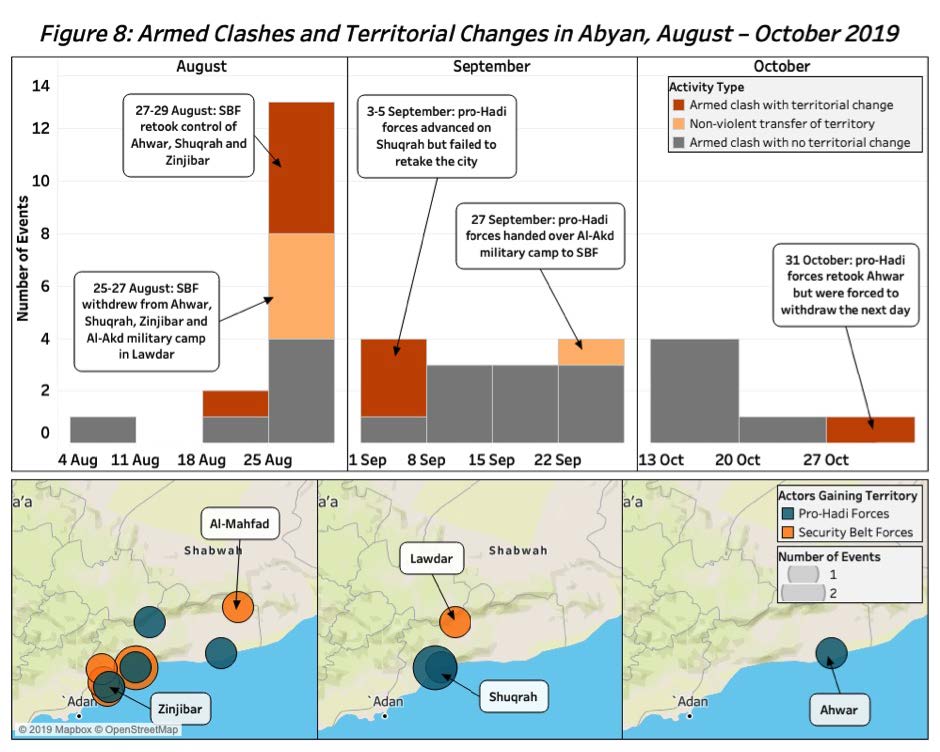

While the AQAP threat dwindled, it remained persistent. New clashes for the control of Zinjibar and other prominent cities throughout the governorate – including Shuqrah, Lawdar, Mudiyah, and Al-Mahfad – erupted between pro-Hadi forces and SBF in August 2019, as the dynamics of the ‘third battle of Aden’ reached Abyan. While STC Vice President Hani bin Braik called for “a general mobilization of all southern forces” in early August (Al-Araby, 7 August 2019), SBF in Abyan attempted the takeover of pro-Hadi positions by the end of the month (Al-Mashhad Al-Janubi, 20 October 2019).

Figure 8 below illustrates how clashes unfolded in Abyan throughout the August-October 2019 period. Most of the political elite, including governor Abu Bakir Husayn Salim, and the Abyan tribes reiterated their support for President Hadi (Al-Masdar, 7 September 2019). However, SBF rapidly seized several of the governorate’s main cities – Shuqrah, Ahwar and Zinjibar – as well as the strategic Al-Akd military camp in Lawdar district. If pro-Hadi forces managed to regain control over Ahwar in late October, they had to withdraw only a day after, reportedly under the UAE’s threat of shelling their positions (Al-Mashhad Al-Yemeni, 1 November 2019).

The recent wave of fighting has also led to a resurgence of AQAP activity: while ACLED records 12 events involving AQAP militants over the seven-month period from January to July 2019, 11 events are recorded from 20 August to 31 October 2019, a period of fewer than three months. In late August 2019, the group temporarily took control of Al-Akd military camp in Lawdar district and expanded its influence in the northeastern district of Al-Mahfad (Al-Janub Al-Yum, 29 August 2019), where another military camp had already been seized for a few hours on 2 August. While continued clashes between pro-Hadi and pro-STC forces in the governorate might pave the way for a sustained increase of AQAP activity, Riyadh will most likely attempt to use its new leadership role in southern Yemen to consolidate the counter-terrorism front of Abyan by bringing both pro-Hadi and pro-STC forces under its control. Like in Aden, its successes in implementing the Riyadh Agreement will be crucial in determining future patterns of political violence in Abyan.

Lahij

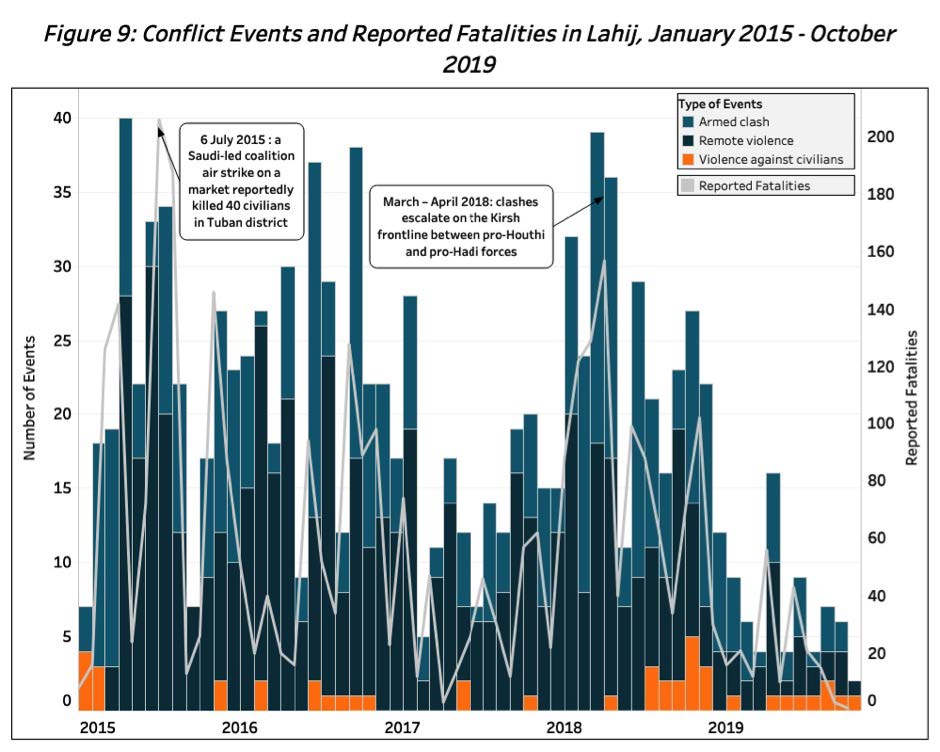

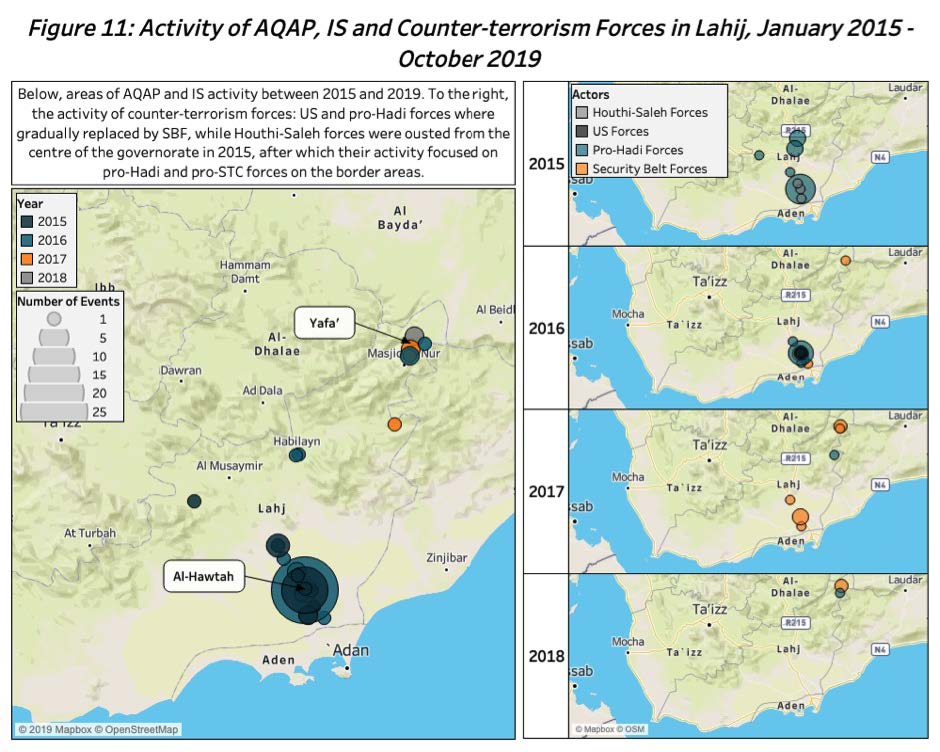

Leaving aside the ‘first battle of Aden’ and the recent drop in recorded events, the governorate of Lahij, located to the north of Aden and the northwest of Abyan, has witnessed a relatively higher number of conflict events compared to its two neighbors since ACLED started recording data in January 2015 (see Figure 9 below). Most notably, Lahij exhibits more than twice the number of estimated fatalities reported in Abyan for the same period (more than 3,300). In large part, this is due to the fact that the nature of the conflict in Lahij is substantially different: since 2015, patterns of political violence are mostly defined by the fight against pro-Houthi forces, which is still a feature of conflict in the governorate in the northern Kirsh frontline. If AQAP and the Islamic State have also exploited the war to expand in Lahij, their activities dwindled after 2016 and completely ceased by the end of 2018, with counter-terrorism operations restricted to Al-Hawtah and Yafa’ districts. Meanwhile, the fighting between pro-Hadi forces and SBF has been extremely limited.

Houthi-Saleh forces first penetrated Lahij governorate from the northern district of Al-Qabbaytah, seizing the city of Kirsh on 24 March 2015. Their rapid military advance led to the capture of Al-Anad military air base and the subsequent abduction of Hadi Minister of Defense Mahmud Al-Subayhi in Al-Hawtah, the capital city of the governorate, the next day (Al-Jazeera, 25 March 2015). The capture of Al-Anad base was a pivotal event of the conflict, which, along with the assault on Aden, contributed in triggering the Saudi-led coalition’s intervention in Yemen. About 50km north of Aden, the military site reportedly hosted the headquarters of US operations in Yemen and displayed launch pads for unmanned Predator drones and/or Hellfire missiles (Lackner, 2014).

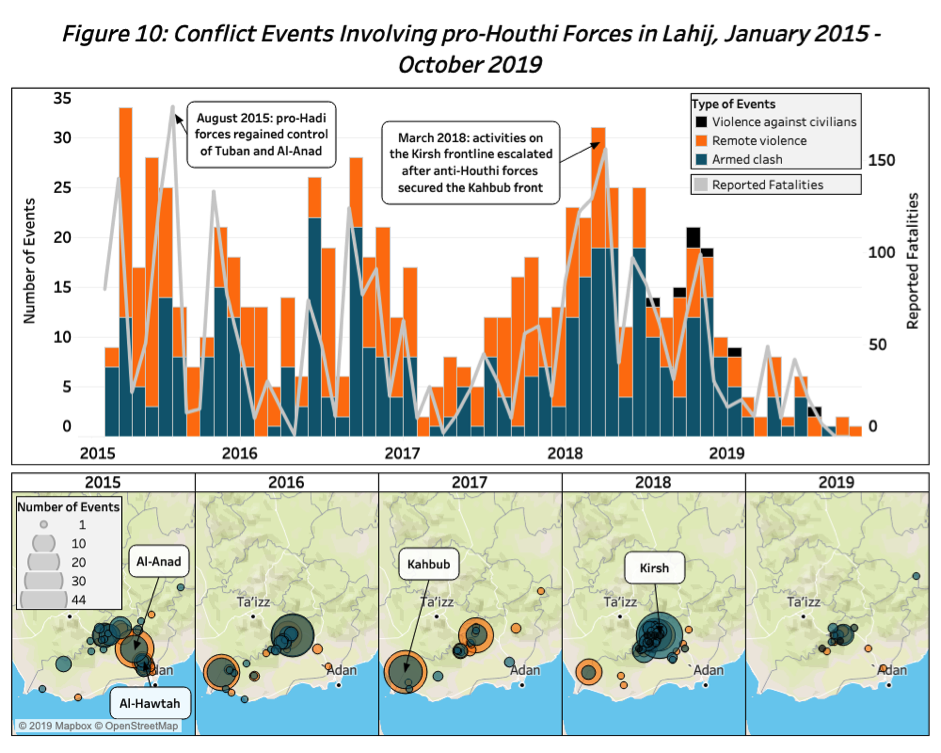

Houthi-Saleh forces maintained a foothold in Tuban district around the capital city of Lahij up to August 2016, but their activities have been mostly focused on the Kirsh frontline since December 2015 through today. From April 2016 to August 2018, fierce fighting was also waged around the strategic Kahbub mountain in Al-Madaribah wa Al-Arah western district, but pro-Houthi forces abandoned this frontline to face the advance of UAE-backed National Resistance Forces on the Tihama coast (ACLED, 10 May 2018; ACLED, 20 July 2018) (see Figure 10 below for geographical references and a timeline of the activity of pro-Houthi forces in the governorate).

In a way similar to what happened in Abyan, the fight against Houthi-Saleh forces seems to have favored an expansion of AQAP’s territorial outreach in Lahij. By the end of January 2016, the organization had gained full control over Al-Hawtah (Critical Threats, 16 February 2016). ACLED data show a peak in AQAP activity in April 2016, followed by a gradual decline and a complete cessation of the group’s activity in early 2018, which can be attributed to counter-terrorism operations that chased the group to neighboring Al-Bayda governorate.

Like in Aden and Abyan, SBF were also established in Lahij, where they started operating in June 2016 under the leadership of Colonel Salih Al-Sayyad, commander of SBF and security director of the governorate. In a November 2016 interview, Al-Sayyad stressed the restored security situation in Al-Hawtah and along the main road of the province, a key infrastructure stretching between Taizz governorate and Aden, connecting the highlands to the western and southern seacoast (Aden Time, 10 November 2016).

ACLED confirms a gradual increase in the role of the SBF in counter-terrorism operations in Lahij, depicted in Figure 11 below. While most operations were conducted by pro-Hadi forces in 2015 and 2016, SBF seem to have taken on the primary counter-terrorism role from 2017 onwards, with operations taken place mostly in Al-Hawtah and Yafa’ districts (see the maps on the right hand side of Figure 11 below). Meanwhile, US-led operations were seemingly very limited.

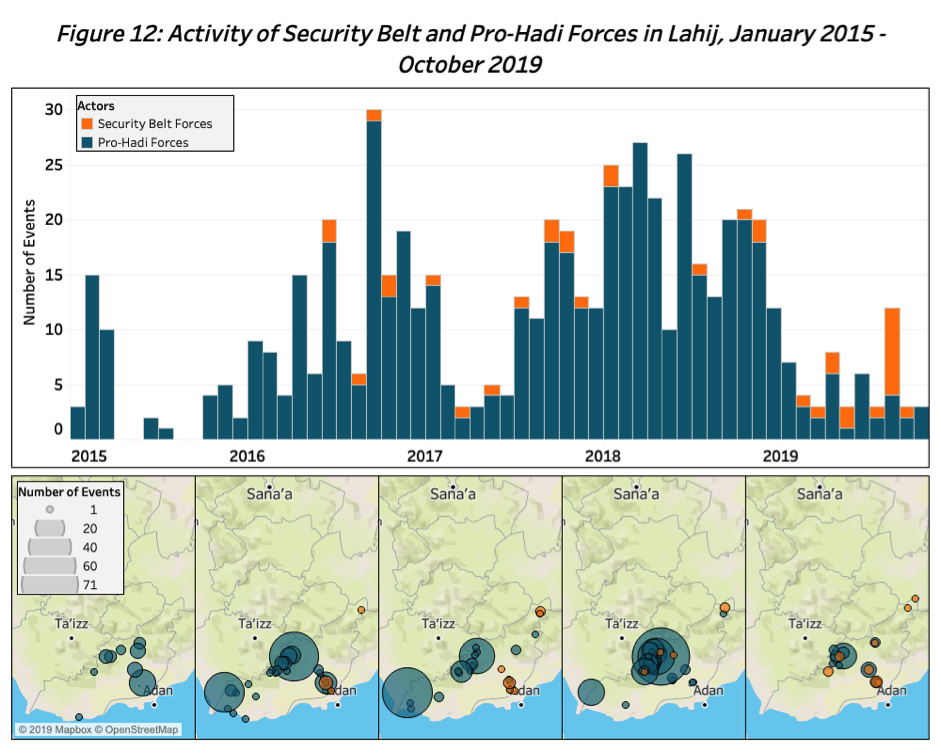

In August 2019, the clashes between pro-Hadi and pro-STC forces that became a major component of the conflict environments of Aden and Abyan governorates only witnessed very localized manifestations in Lahij – in Al-Hawtah and Radfan districts. This can arguably be explained by the fact that pro-Hadi forces seem to have focused largely on the fight against pro-Houthi forces in the western and northern frontlines of the governorate. This is while SBF secured positions in non-frontline areas. As visualized in Figure 12 below, this results in a significant decrease in the role of pro-Hadi forces in 2019 following the cessation of fighting in Kahbub in late 2018 and the large diminution of fighting in Kirsh in 2019. Attesting the influence gained by SBF in the governorate, recent reports suggest that they could now be replacing pro-Hadi forces in the northern Kirsh frontline (Aden Al-Ghad, 19 November 2019).

Arguably, this assertion of the role of SBF and the concurrent decrease of the influence of pro-Hadi forces was made possible by the alignment of both the political elite and a significant segment of the Lahij population with the STC. While Abyan is the argued stronghold of the pro-Hadi Zomra elite, the elites of Lahij can be understood as identifying with the historical Toghma group, supporting the STC and its vision for an independent southern Yemen (International Crisis Group, 30 August 2019). As shown by a recent study conducted by the Yemen Polling Center, this also resonates at the ground level (Yemen Polling Center, 25 November 2019). According to the organization, the STC enjoys its strongest support across all governorates of southern Yemen in Lahij.

This unparalleled support has most likely helped the SBF avoid clashes with pro-Hadi forces after the ‘third battle of Aden’ erupted. Although governor Ahmad Al-Turki officially supported the Hadi government, most pro-Hadi units remained engaged on the Kirsh frontline and did not mobilize against SBF, unlike what happened in Abyan. As pro-STC forces therefore seem to go nearly unchallenged in Lahij, future patterns of political violence in the governorate will likely be less dependent on the ability of Saudi Arabia to implement the Riyadh Agreement than in neighboring Aden and Abyan.

Conclusion

After an initial review of the dynamics at play in the governorates of Shabwah and Hadramawt (ACLED, 9 May 2019), this series on southern Yemen looks at the island of Socotra and the easternmost governorate of Mahrah (ACLED, 31 May 2019), before concluding with Aden, Abyan and Lahij in this report. The aim of the series is to uncover the various patterns of political violence playing out in the south of Yemen and its different actors, amid a context of increased state fragmentation exacerbated by the current conflict.

Along with the fight against militant jihadi groups, the main feature of political violence in most of southern Yemen in the last five years has been the emergence of pro-STC and UAE-backed armed forces, which effectively operate as paramilitary forces despite being formal state actors of the Hadi government. The establishment of these forces, however, has encountered mixed results depending on local contexts. As seen in this piece, SBF, for instance, have gone rather unchallenged in Lahij, where they seem to enjoy considerable support from political elites and the population. In Abyan, the province of origin of President Hadi, they have, on the other hand, been faced with opposition by pro-Hadi forces. In Aden, they seem to have gained significant influence — they managed to overtake the city twice in the past two years — but this has been restrained by Riyadh, which cannot afford to see the Hadi government ousted from the country’s interim capital after it already lost Sana’a in 2014.

In Shabwah, if the Shabwani Elite Forces have managed to become primary actors of the governorate based on the fight against militant jihadi groups, underlying tensions with pro-Hadi forces led to outbreaks of violence in August 2019. These can arguably be explained by the economic significance of the governorate, which, in addition to housing its own oil and gas fields, also acts as a crucial gateway for the gas coming from neighboring Marib, delivered at the controversial Balhaf facility (L’Observatoire des armements, SumOfUs and Les Amis de la Terre France, 7 November 2019). Control over Shabwah therefore yields economic power.

On the other hand, clashes did not erupt in neighboring Hadramawt, where Hadrami Elite Forces (HEF) also established themselves as primary actors after ousting AQAP from its capital Mukalla in April 2015. Unlike in Shabwah, a tacit understanding seems to exist between pro-Hadi and HEF in Hadramawt. Despite recurrent calls from the STC leadership for the takeover of inland Hadramawt by the HEF, the latter remains focused on the coastal regions, while pro-Hadi forces operate mostly in Hadramawt Valley and the upper desert areas. Arguably, the strong subnational Hadrami identity also prevents a splitting up of the governorate.

In Socotra and Mahrah, the establishment of local pro-STC forces has been much less successful. Despite initial reports on the formation of ‘Socotri Elite Forces’, pro-STC forces on the island are now referred to as SBF. If their successes in establishing positions and gaining popularity is yet not entirely clear, a spike in protests calling for the dismissal of the local governor has been registered by ACLED since June 2019, coinciding with the arrival of SBF on the island. In Mahrah, initial reports of the formation of Mahri Elite Forces in February 2019 never materialized. All Saudi-led coalition activity in the governorate is being faced with strong popular opposition, which is likely, at least in part, instrumentalized by neighboring Oman. Former Deputy for Desert Affairs Ali Salim Al-Hurayzi, for instance, announced the creation of the Southern National Salvation Council in October 2019 as a rival to the STC, which he accuses of being a foreign agent in Yemen (Masa Press, 6 November 2019).

If similarities can be found across most governorates, the above shows that southern Yemen cannot be addressed as a monolithic unit of study. Despite actors such as the STC claiming to be the sole representative of the southern people, the specificities of each local context needs to be taken into account in any attempt at stabilizing southern Yemen.

© 2019 Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). All rights reserved.