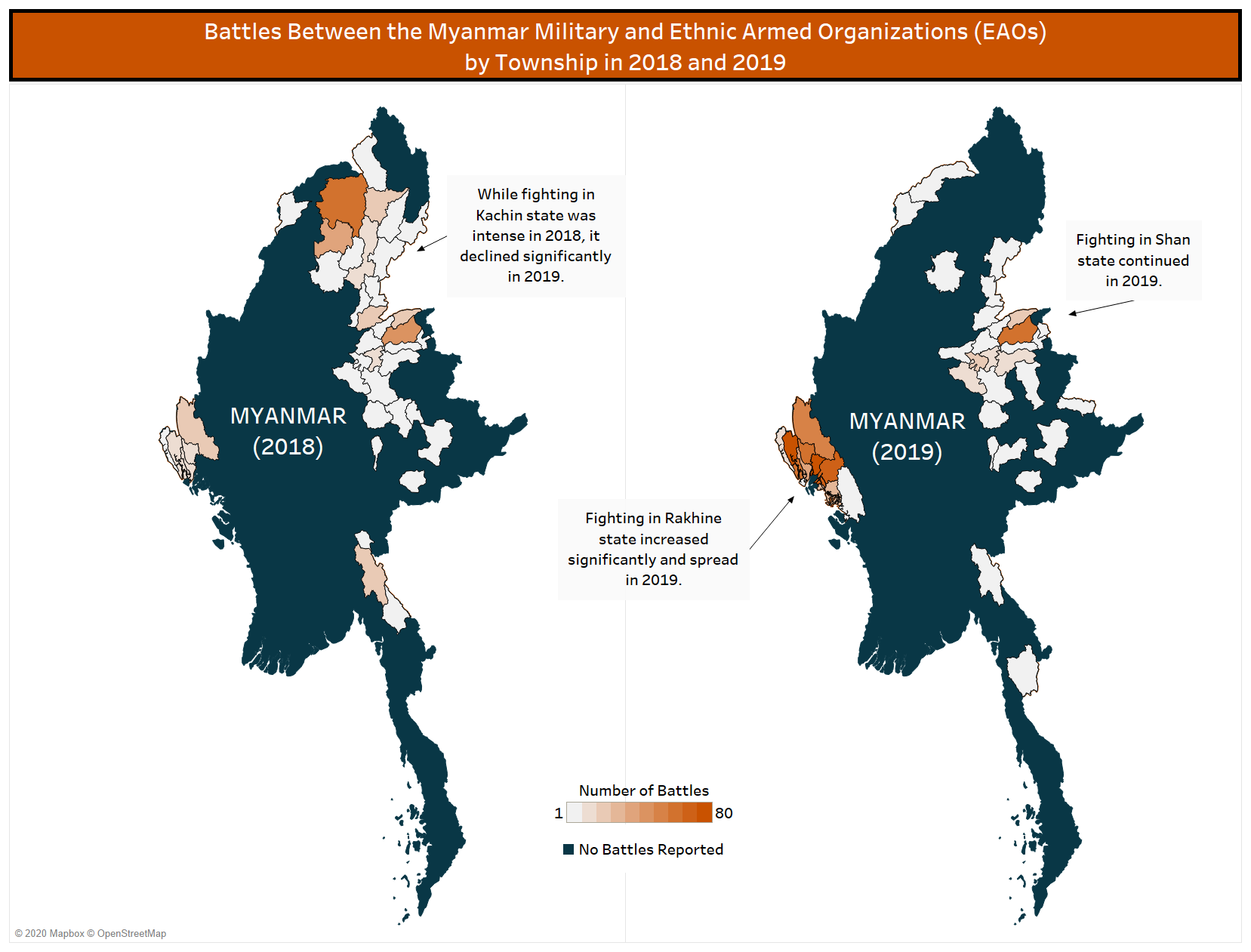

Disorder spiked in Myanmar last year. ACLED records an increase of every event type, from battles and violence against civilians to riots and protests. Despite unilateral ceasefires declared by both the military and an alliance of ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) during the course of the year, armed conflict rose in 2019 and was especially intense in Rakhine and Shan states (see figure below). No progress was made towards resolving long-standing grievances among non-Burman communities and, in fact, many such grievances were deepened as a result of misguided government and military policies. As Myanmar enters an election year, conflict across the country seems likely to continue unabated.

ULA/AA Moves to Establish a Base in Rakhine State

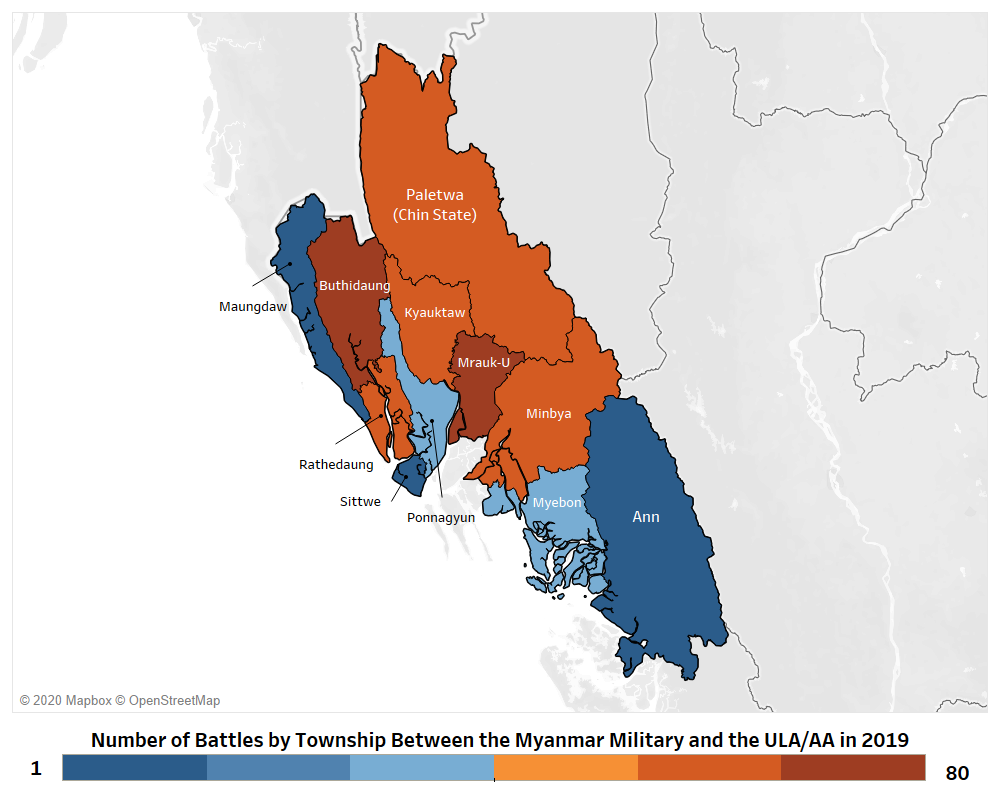

The unilateral ceasefire declared by the military at the end of 2018 covered Kachin and Shan states, but left out the western part of the country, including Rakhine state (Irrawaddy, 23 September 2019). Shortly thereafter, conflict between the military and the United League of Arakan/Arakan Army (ULA/AA), an EAO comprised of ethnic Rakhine fighting for greater autonomy, flared (see figure below).

While intermittent fighting between the military and the ULA/AA has been reported since 2015, ACLED records a marked increase in battles last year. The conflict also spread southwards in 2019 to townships in which battles had not been previously recorded, including Mrauk-U, Sittwe, Myebon, Minbya, and Ann townships. The largest number of battles were recorded in Mrauk-U township, a place notable for its historical importance as the capital of the old Arakan (Rakhine) Kingdom (Transnational Institute, December 2019).

The current conflict in Rakhine state is inextricably linked to the conflict that has been ongoing in Kachin and northern Shan states for nearly a decade. The ULA/AA’s alliance with stronger, better armed groups in the region allowed it to build up and train its own forces. The formation of two EAO alliances — the Federal Political Negotiation Consultative Committee (FPNCC) led by the United Wa State Party/United Wa State Army (UWSP/UWSA), and the Northern Alliance led by the Kachin Independence Organization/Kachin Independence Army (KIO/KIA) — has provided an avenue for the ULA/AA to strengthen its position in informal negotiations with the government peace team. The ULA/AA has been denied participation in formal negotiations aimed at having ethnic armed groups sign the 2015 Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) (International Crisis Group, 24 September 2019).

Having been influenced by allied groups such as the UWSP/UWSA, the ULA/AA is clear in its ambition to gain the level of autonomy that the military has granted the Wa (Frontier Myanmar, 29 May 2019). The 30th anniversary of the ceasefire between the UWSP/UWSA and the military earlier in 2019 only served to highlight the unequal treatment and rights granted to different ethnic groups. This differential treatment contributes to further conflict, as many EAOs vie for greater autonomy.

As the ULA/AA portrays itself as fighting on behalf of the Rakhine ethnic group, whose ancient kingdom was defeated by Burman armies, there is little to suggest that they will lose the resolve to engage the military. There is significant popular support for the ULA/AA, and, similar to other EAOs, the group recently announced that it has plans to tax local businesses in areas under its control in a bid to establish governance structures (Radio Free Asia, 31 December 2019).

The ULA/AA has also joined with two other members of the Northern Alliance — the Palaung State Liberation Front/Ta’ang National Liberation Army (PSLF/TNLA) and Myanmar National Truth and Justice Party/Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNTJP/MNDAA) — to form a new grouping: the Brotherhood Alliance. In August, the Brotherhood Alliance carried out attacks in Shan state and, notably, in the Mandalay region, on the Defense Service Technological Academy (Irrawaddy, 15 August 2019). As a result, the last two months of the year were marked by increased fighting in areas where the PSLF/TNLA are active in Shan state.

The KIO/KIA, a member of the Northern Alliance, which also includes all the groups in the Brotherhood Alliance, was not involved in the August attacks. There was likewise a significant decline in clashes between the KIO/KIA and the military in 2019 following a peak in 2018. While there appears to be greater effort aimed at persuading the group to reconsider signing the NCA, the recent arrest of two members of the influential Kachin Baptist Convention (KBC) under the Unlawful Associations Act, a law which has been used to harass ethnic minorities alleged to have connections to ethnic armed groups, undermines these efforts (Radio Free Asia, 7 February 2020).

Meanwhile, the government has labeled the ULA/AA a “terrorist” group, even as it has included them in discussions along with other members of the Northern Alliance. This incongruence between discourse and action harms any talk of peace. The unilateral ceasefire declared by the military ended in September 2019. The Northern Alliance announced that it was extending its unilateral ceasefire until the end of February 2020 (Myanmar Times, 2 January 2020). Neither ceasefire declaration has done much to lessen the ongoing conflicts.

Further, given that most ethnic organizations — whether armed or not — advocate for greater autonomy in their respective states, the National League for Democracy (NLD) government’s decision when it came to power in 2016 to appoint its own party member as minister of Rakhine state rather than a member of the popular Arakan National Party (ANP) only served to exacerbate tension in the region (International Crisis Group, 24 January 2019).

Recent efforts by the NLD to form an ethnic affairs wing of the party have been met with little enthusiasm, as this move is seen as attempting to co-opt ethnic minority support rather than work in alliance with already existing ethnic-based parties. Several ethnic-based parties recently expressed dismay over the lack of progress the NLD has made in moving the country towards a more decentralized form of governance that would aid in lessening armed conflict in the country (Myanmar Times, 24 January 2020).

NCA No Guarantee of Peace

While most of the battles recorded in 2019 were between the military and EAOs that have not signed the NCA, signing it has been no guarantee of peace. During the past year, intermittent clashes were reported between the military and several NCA signatories.

In Kayin state, the military continued with road construction in areas controlled by Karen National Union/Karen National Liberation Army (KNU/KNLA) brigades 3 and 5. The road construction project, which has sparked clashes over the past few years, is seen as a violation of the NCA (Karen News, 10 December 2019). The KNU/KNLA suspended its participation in formal peace talks with the military in late 2018 (Frontier Myanmar, 29 October 2018). While meetings have since been held to review concerns regarding the road construction project, tensions remain.

Similarly, at the end of 2019, clashes took place between the military and the New Mon State Party/Mon National Liberation Army (NMSP/MNLA) in the Three Pagodas Pass area, marking the first reports of conflict between the groups since the NMSP/MNLA signed the NCA in 2018. The clashes led several hundred villagers to flee into Thailand. While the military eventually retreated, their decision to enter a NMSP/MNLA base was also viewed as violating the NCA (Independent Mon News Agency, 17 January 2019).

While the Restoration Council of Shan State/Shan State Army-South (RCSS/SSA-S) had suspended its participation in the NCA monitoring mechanisms in late 2018, it recently indicated it was open to the government’s efforts to hold the fourth session of a national-level peace conference in 2020 (Irrawaddy, 17 January 2020). Aside from clashing with the military, the RCSS/SSA-S has frequently fought with the PSLF/TNLA over territorial disputes in northern Shan state, reflecting the intra-EAO conflicts that remain unaddressed in the current peace process.

As seen in these examples, the dichotomy that has been established in which NCA signatories are contrasted with non-signatories is misleading. There is little to suggest that signing the NCA will lead to a resolution of grievances that all EAOs share. Both signatories and non-signatories have similar stated goals, but one group has chosen to work within the NCA framework while the other has maintained that certain issues must be resolved before entering into such an agreement (Asia Times, 19 March 2019). While conflict may have declined in areas controlled by those groups that have signed the NCA, the threat of renewed conflict is constant, as evidenced by continued reports of clashes.

Violence against Civilians in Rakhine State Increases

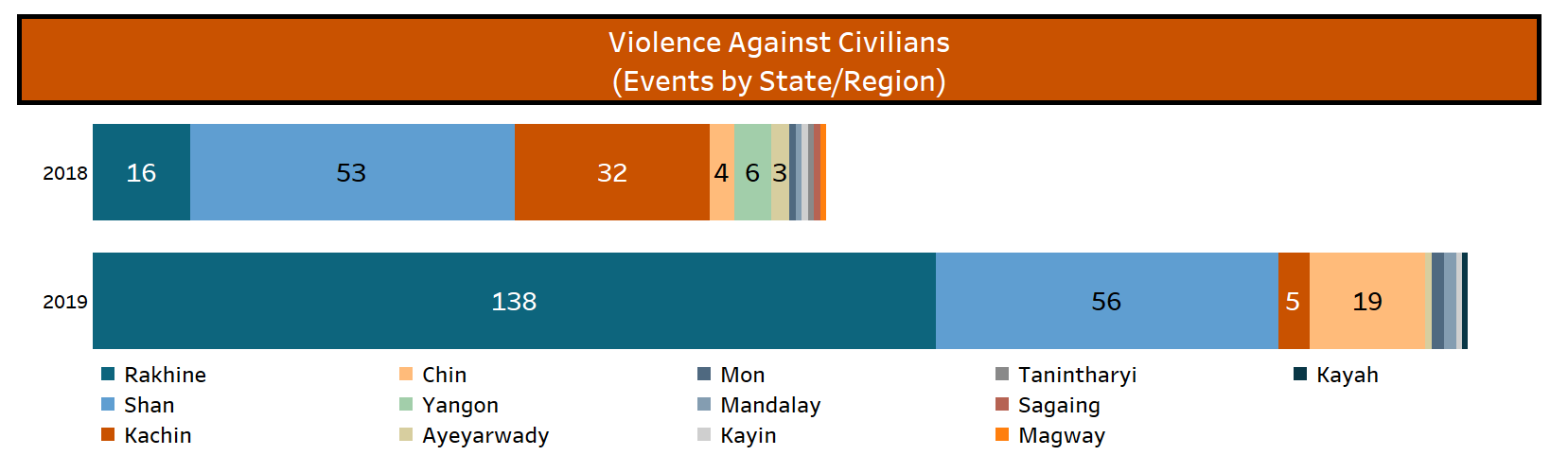

Throughout 2019, civilians were displaced, targeted by the military and ethnic armed groups, caught in the crossfire of battles, and at risk of shelling and landmines. Violence against civilians, which is a subset of all civilian targeting, has been on the rise, particularly in Rakhine state (see figure below). The number of violence against civilians events in Rakhine state last year is nearly nine times higher than the number of events reported in 2018.

The majority of these events were perpetrated by state forces. Such violence has impacted villagers across ethnicities in Rakhine state: both Rakhine and Rohingya communities have been affected. In April, six Rohingya villagers were reportedly killed when they were fired on by the military. In May, seven Rakhine villagers were reportedly shot and killed while in military custody.

The ULA/AA has also targeted civilians, arguing that the military uses civilian cover to carry out operations and that government officials are providing intelligence about its movements to the military. The group began a campaign of abductions targeting civilians, government officials, and military personnel, with multiple cases reported throughout 2019. In November, a member of parliament from the NLD was abducted and was only recently released (Reuters, 22 January 2020). In December, the Buthidaung township NLD chairman was abducted and later died from shelling in the area, according to the ULA/AA.

Limited Political Agency for Non-Burman Communities

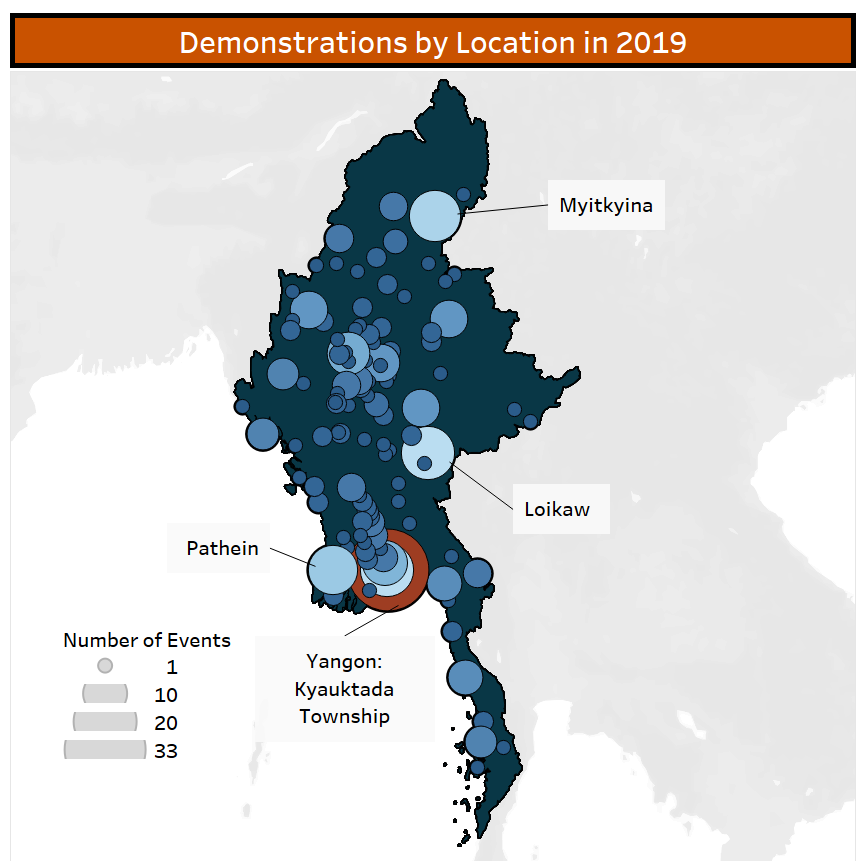

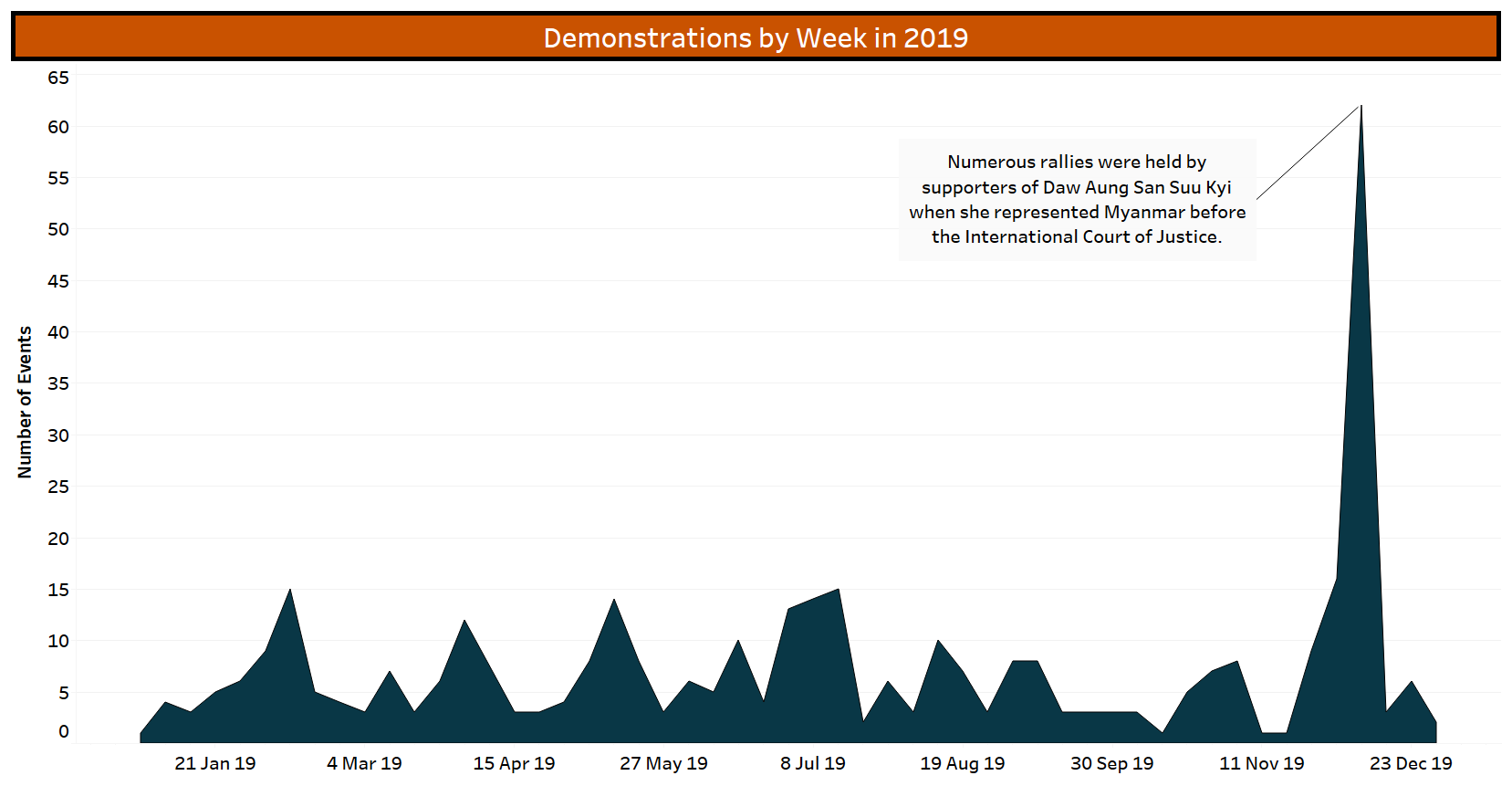

In 2019, there were twice the number of demonstration events in all of Myanmar relative to 2018. Notably, demonstration activity has increasingly stemmed from policies which primarily affect non-Burman communities. Such demonstrations are motivated by opposition to actions that are seen as promoting a policy of Burmanization, as well as calls for an end to the ongoing conflicts in the border regions.

The highest number of demonstration events occurred in Kyauktada and Dagon townships in the Yangon region. Demonstration activity was subsequently highest in Loikaw township in Kayah state with 14 reported events, followed by Myitkyina township in Kachin state with 13 reported events.

Authorities responded violently to demonstrations in Loikaw in February, with protest leaders subsequently imprisoned (Irrawaddy, 26 August 2019). The demonstrators were protesting the government-backed installation of statues of the Burmese independence leader, Aung San, in non-Burman areas, despite public opposition. Many of those opposed to the statues want the leaders of their own ethnic groups recognized as well.

Similarly, in August, Karen activists attempting to mark Karen Martyr’s Day were detained and sentenced after using the term ‘martyr’ during their gathering in Yangon (Karen News, 20 September 2019). The designation of ‘martyrs’ is a contentious issue, as it is a term that has been used to describe political leaders, including Aung San, who were assassinated on 19 July 1947 prior to Burma’s independence from Britain. As with the debate over the Aung San statues, many Karen ethnic leaders have argued for the freedom to recognize and honor the leaders and martyrs of all ethnic groups.

Additionally, there were a number of anti-war demonstrations in 2019. These demonstrations were led by youth aiming to highlight the suffering that civilians have faced during the country’s various conflicts. When several Kachin youth staged a performance to commemorate the eighth anniversary of the start of renewed conflict in Kachin state, they were jailed (Frontier Myanmar, 3 September 2019).

While demonstrations over issues of ethnic equality were notable last year, so too were the ongoing nationalist demonstrations, often led by Buddhist monks and other military-backed groups, with the stated aim of protecting race and religion. The NLD also showed that it could manipulate nationalist sentiment to its advantage by tying public support for NLD leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi to the larger narrative of defending the nation when she represented Myanmar at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) (Irrawaddy, 9 December 2019). The ICJ is now in the process of determining whether the military’s campaign of violence against the Rohingya in Rakhine state in 2017 constitutes genocide. The case sparked a year-end spike in the number of demonstration events across the country (see figure below).

Prospects for 2020

With general elections scheduled for later in the year, there is concern that ongoing fighting in Rakhine and Shan states could prevent the vote from being held in those areas. While the NCA framework continues to dominate discussions of peace, the grievances of non-Burman communities and the possible political channels that could be used to address such grievances remain overlooked. 2020 is likely to be a violent year unless there is genuine discussion aimed at bringing about a federal system that respects the decades-long calls for equality and self-determination.