At the height of the Arab Spring in February 2011, a mass protest movement took to the streets in Bahrain calling for democratic reforms, human rights protections, and an end to corruption. Nine years ago this month, the Bahraini government, backed by a contingent of Saudi and Emirati security forces, declared a state of emergency and launched a violent crackdown, destroying the site of the main protest encampment and the symbol of the movement at Manama’s Pearl Roundabout (The Guardian, 18 March 2011). The authorities killed dozens of protesters and arrested hundreds of activists, critics, and religious leaders, dissolving opposition political groups and closing all independent media outlets (The Atlantic, 21 January 2015; OHCHR, 16 June 2017; Human Rights Watch, 18 June 2017).

Nearly a decade later, new data confirm that despite severe restrictions on free press, expression, and assembly (Human Rights Watch, 14 January 2020), hundreds of protests and riots continue across the country every year. To address coverage gaps left by pervasive censorship, ACLED has completed supplemental data collection drawing on information from over 20 ‘new media’ sources. ‘New media’ (e.g. Twitter, Telegram, WhatsApp) can be a powerful supplemental source, but vary widely in terms of quality. As a result, ACLED does not crowdsource or scrape large amounts of social media, but instead takes a targeted approach to the inclusion of new media through the establishment of direct relationships with each source or the verification of the quality of each source.1 This new supplementation adds more than 7,000 events to the Bahrain dataset, capturing a range of disorder from the beginning of coverage in 2016 to the present.2

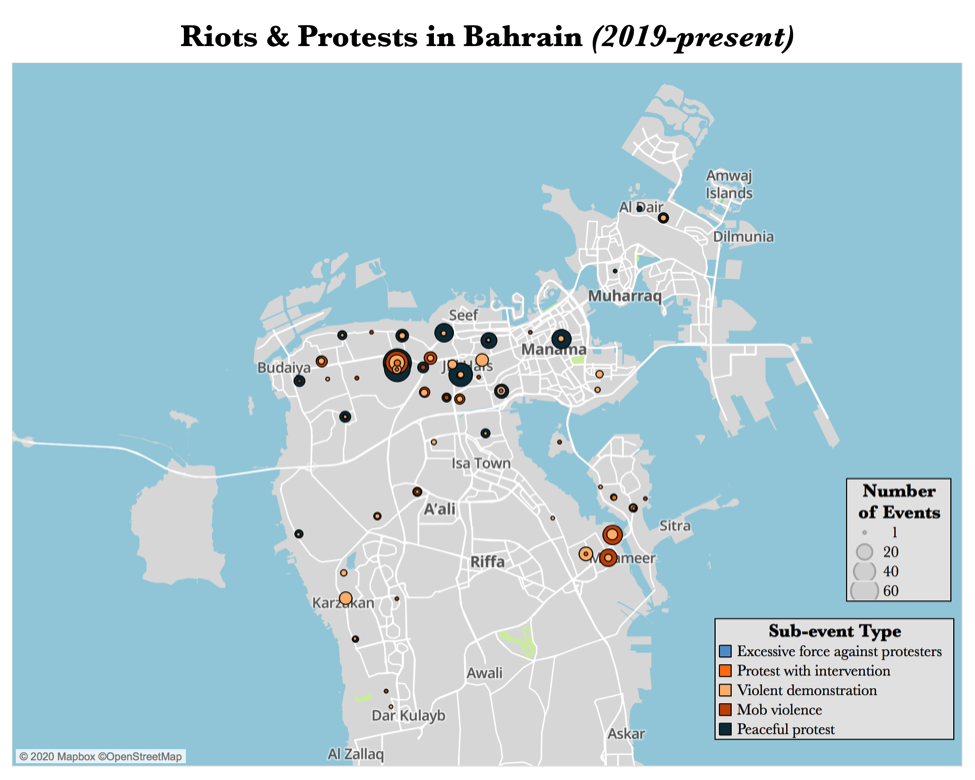

Peaceful protests account for the majority of the newly added events, with over 4,400 recorded since 2016. More than 140 of these events faced some form of intervention, such as police firing teargas or detaining activists. Nearly 2,600 new events are riots, with more than 1,800 violent demonstration events and over 700 cases of mob violence.

In total, ACLED now records approximately 9,000 events in Bahrain from January 2016 to March 2020. Demonstration events account for 99% of all disorder in the country, with the remaining 1% consisting of violence against civilians, predominantly perpetrated by state forces; rare clashes between the authorities and anti-government militia groups, such as Saraya Al Ashtar; and sporadic bomb attacks. More than 20 fatalities are reported between 2016 and early 2020.

The most active group involved in demonstrations is the February 14 Coalition, a decentralized organization primarily consisting of youth activists. Named for the start date of Bahrain’s 2011 uprising,3 the Coalition is not affiliated with any formal political groups and contains both Shiite and Sunni members. It does not maintain a clear leadership hierarchy, and its members communicate mostly through social networks such as Facebook to organize demonstrations. Since 2011, the Coalition has called for the fall of the Al Khalifa monarchy, and the governments of Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Egypt have designated it as a ‘terrorist group.’ Many demonstrations are also led by the Shiite community at large. Though the government does not release demographic information, Shiites are believed to make up 55% to 70% of Bahrain’s citizen population (CEIP, February 2019; Pew Research Center, 27 January 2011). Despite accounting for a majority, the Shiite community is marginalized and faces discrimination by the government, which is dominated by the Sunni royal family (CEIP, February 2019). Attacks on Shiite activists, clerics, and leaders in Bahrain and neighboring Saudi Arabia regularly trigger large demonstrations.

The data show spikes in demonstration activity around executions and extrajudicial killings committed by the government. In January 2017, demonstrations surged after the authorities executed three Shiite men charged with a deadly attack on security forces in 2014, despite allegations that the prisoners were tortured and convicted in an unfair trial (Amnesty International, 17 January 2017). Mass protests broke out again in February 2017 after security forces killed three escaped prisoners, coinciding with the anniversary of the 2011 uprising (Amnesty International, 14 February 2017). And in May 2017, five protesters were killed in a police raid on a sit-in outside the home of a prominent religious leader in Diraz, triggering another wave of demonstrations. With more than 80 demonstration events already recorded through mid-March, Bahrain is likely to face continued unrest well into 2020.

All ACLED data can be accessed through the Data Export Tool and Curated Data Files.

Notes

1 For more on ACLED sourcing methodology, see this primer.

2 The term disorder is used to refer to all political violence and demonstrations.

3 The group also takes its name from the date of the 2001 referendum on the National Action Charter, a reform package proposed by Bahrain’s king. The government’s failure to fully implement the reforms was a major motivating factor behind the 2011 protest movement, with 14 February 2011 marking the 10-year anniversary of the referendum.