On 10 December 2019, leaders of Ukraine, Russia, Germany, and France met in Paris in the ‘Normandy’ format1 to discuss peace plans for the Donbas region of Ukraine, where the conflict between Russia-backed separatist rebels and Ukrainian government forces has now entered its seventh year. Although frontlines have stabilized, fighting continues on a daily basis. At the latest Normandy format meeting, the parties agreed to plans for a ceasefire, the disengagement of forces in three areas, a prisoner exchange, and steps toward local elections in Donbas. However, to date, only the prisoner exchange has taken place. Progress on local elections ground to a halt over crucial differences between Ukraine and Russia under what conditions these should be held. What are the prospects for the ceasefire agreement and disengagement of forces?

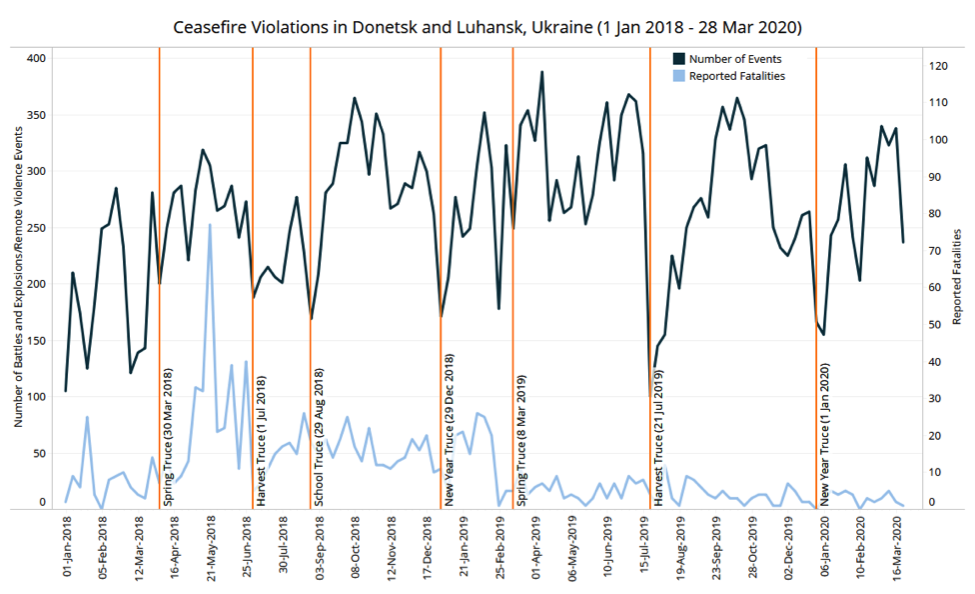

This is not the first time the conflict parties committed to a ceasefire: they made two major peace agreements, which included a ceasefire among other provisions, in 2014 with the Minsk I accord and in 2015 with the Minsk II accord. Minsk II remains the foundation for the current peace talks, with intermediate talks and agreements made by the Trilateral Contact Group on Ukraine (TCG), where representatives of Ukraine, Russia, and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) meet to discuss diplomatic resolutions. Representatives from the separatist rebel groups also take part. Since 2018, the TCG has announced seven agreements on a ‘total’ ceasefire, but their effect has been limited. While each time a sharp reduction in fighting was recorded — by one-third, on average — clashes never fully stopped. Within weeks, fighting would return to levels similar to before the ceasefire took effect (see graph below).

The full implementation of a ceasefire in Donbas could be complicated by the varying allegiances and command structures of the units fighting on the frontline.

Prior to April 2018, operations of the Ukrainian government in Donbas were run by the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) Anti-Terrorist Operation headquarters, which coordinated among the military forces, National Guard and Security Service, but failed to provide a clear chain of command (RAND, 5 October 2016). Previously independent volunteer units that were instrumental to the war effort in 2014-2015, were forced to join the National Guard, part of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, but continue to have considerable independence from central government command and in some cases maintain separate recruitment, training and financial support structures (Deutsche Welle, 30 October 2018; Kyiv Post, 1 February 2019). In addition, these units and other armed groups operating at the frontline have links to nationalist political parties that oppose peace concessions, such as Azov Battalion linked to the National Corps party (Atlantic Council, 19 March 2020). In 2018, ongoing reform of the armed forces, and centralisation under a new military operation of the Joint Forces Operation (JFO) Headquarters, headed by the Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces, created more coherent command over the government’s operations in Donbas (Kyiv Post, 30 April 2018). While the volunteer units, like Azov Battalion, continue to operate semi-independently, their military actions appear mostly in line with overall JFO command. Their opposition to the government’s negotiations centers around politics, rather than attempting to undermine the ceasefire at the frontline.

The separatist rebels have their own commands for the unrecognized Donetsk People’s Republic (DNR) and Luhansk People’s Republic (LNR), which coordinate in the loose coalition structure of the United Armed Forces of Novorossiya (NAF). Russia, however, plays a prominent role in their de facto control. While denied by the Kremlin, it is well established that Russian military forces fought in Donbas at the height of the conflict in 2014 and 2015 (RBC, 2 October 2014; Atlantic Council, 15 October 2015). The DNR and LNR quasi-governments are maintained with significant support from Russia. The exact extent to which Russian forces currently operate in Donbas is unclear. For example, electronic warfare units that are likely operated by Russian forces have been verified operating in LNR and DNR territory since 2019 (DFRLab, 23 May 2019; OSCE, 18 February 2020). By estimates of the Ukrainian military, about 2000 Russian military advisers, instructors, and command and operational support staff operate in Donbas (BBC, 17 April 2019). In addition, DNR and LNR forces include, among others, Russian mercenaries and Russian volunteers, some with links to radical groups (Institute for the Study of War, 15 September 2017), in addition to Ukrainian locals who have increasingly been sidelined since the start of the conflict (Crisis Group, 16 July 2019). These forces are organized into the 1st and 2nd Army Corps and reportedly headed by Russian commanders. The Ukrainian military claims this gives Russian leadership ‘complete’ control over the separatist rebel side of the conflict, enabling the Kremlin to escalate the fighting ‘within hours after their orders’ (BBC, 17 April 2019). Despite this, competing factions have led to infighting and leadership turnovers over the past years, with clashes between LNR and DNR units (DFRLab, 21 November 2017) and multiple LNR and DNR commanders assassinated (Meduza, 1 June 2019). Reportedly, some of these incidents were the result of turf wars between the Russian security service (FSB) and Russian military intelligence (GRU), showing that the Russian command level is not entirely unitary (Warsaw Institute, 4 December 2017). Turf wars aside, however, the idea of these actors openly defying Kremlin orders on a ceasefire or peace agreement seems rather unlikely.

The implementation of ceasefires could also be complicated by difficulties in communication and verification. There are accounts of soldiers hearing of a ceasefire on television, without having received instructions from the chain of command (OSCE, 30 August 2017). Whether this is intentional or inadvertent is hard to verify. It can also be difficult to identify which units violate the ceasefires, as OSCE observers cannot monitor the entirety of the frontline continuously. These factors provide plausible deniability to potential spoiler actors, allowing them to blame the other side or rogue local commanders for ceasefire violations. With each shot fired prompting ‘defensive’ return fire, a truce can quickly break down across the line. Still, a ceasefire break down across the entire 450km frontline might have occurred just once due to miscommunication or local rogue commanders, but it cannot explain why ceasefires failed seven times over the past two years. Rather, it seems that one, or both, of the conflict parties do not receive strict orders from the political leadership to maintain the ceasefire, and may even receive orders to increase shelling at times. This indicates that the ceasefire agreements have been halfheartedly enforced paper agreements at best, or cynical manipulations of the peace process at worst.

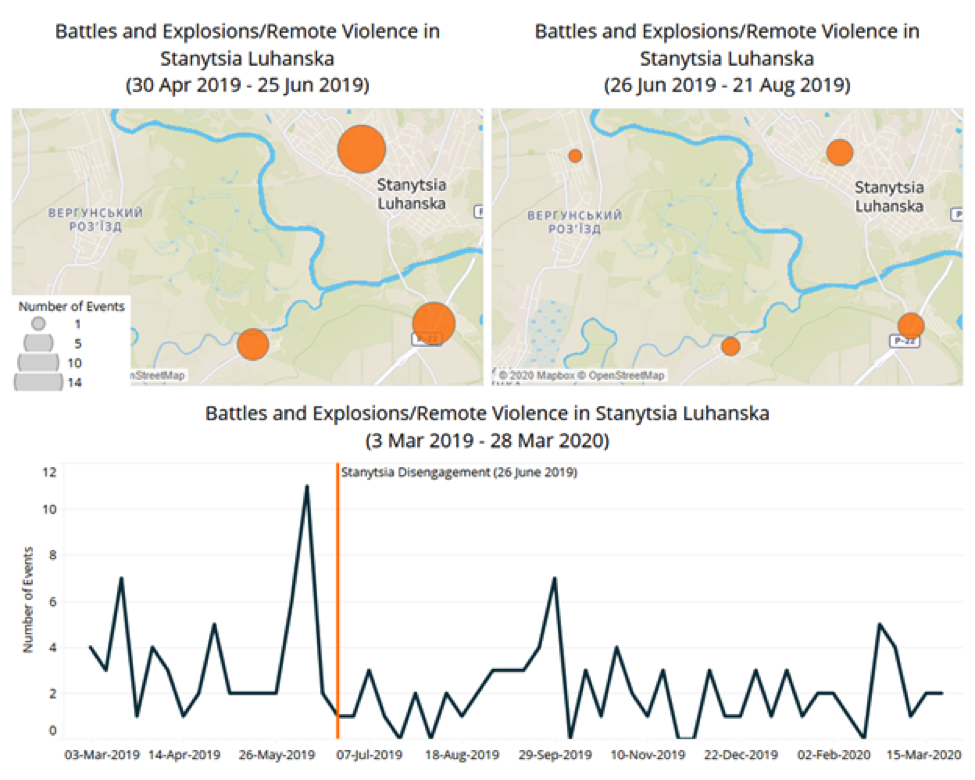

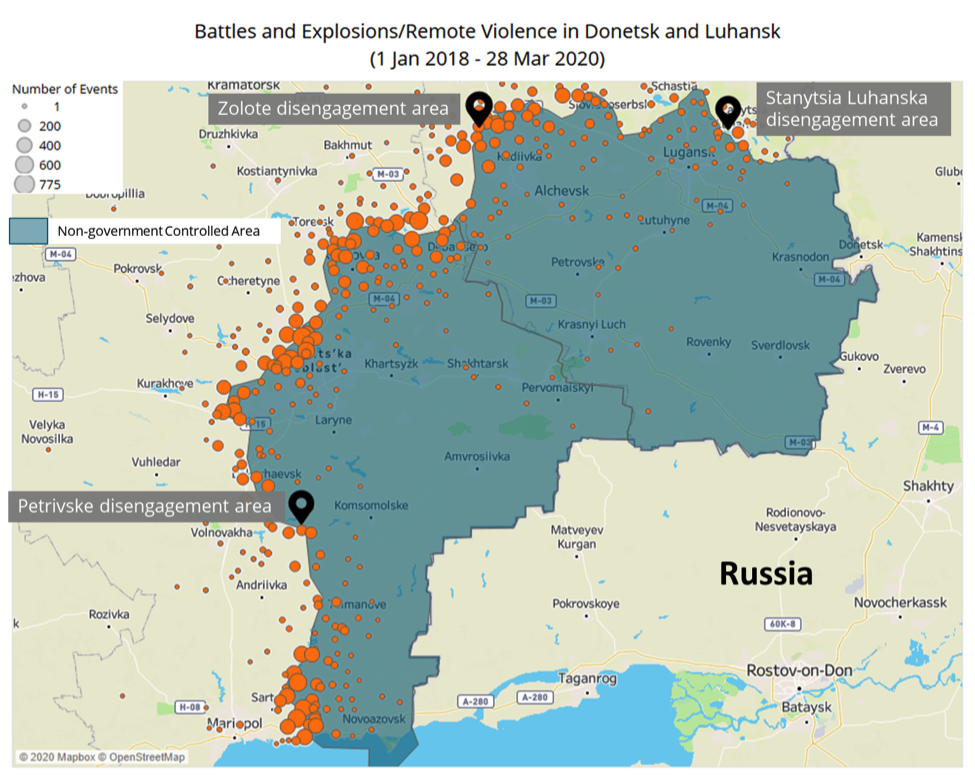

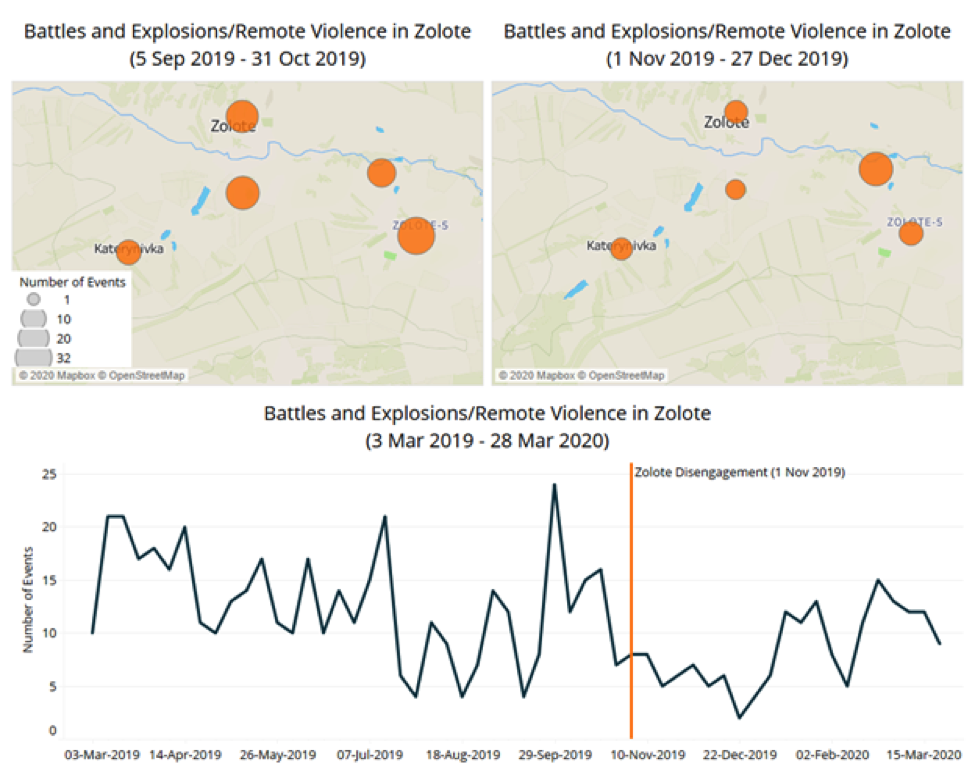

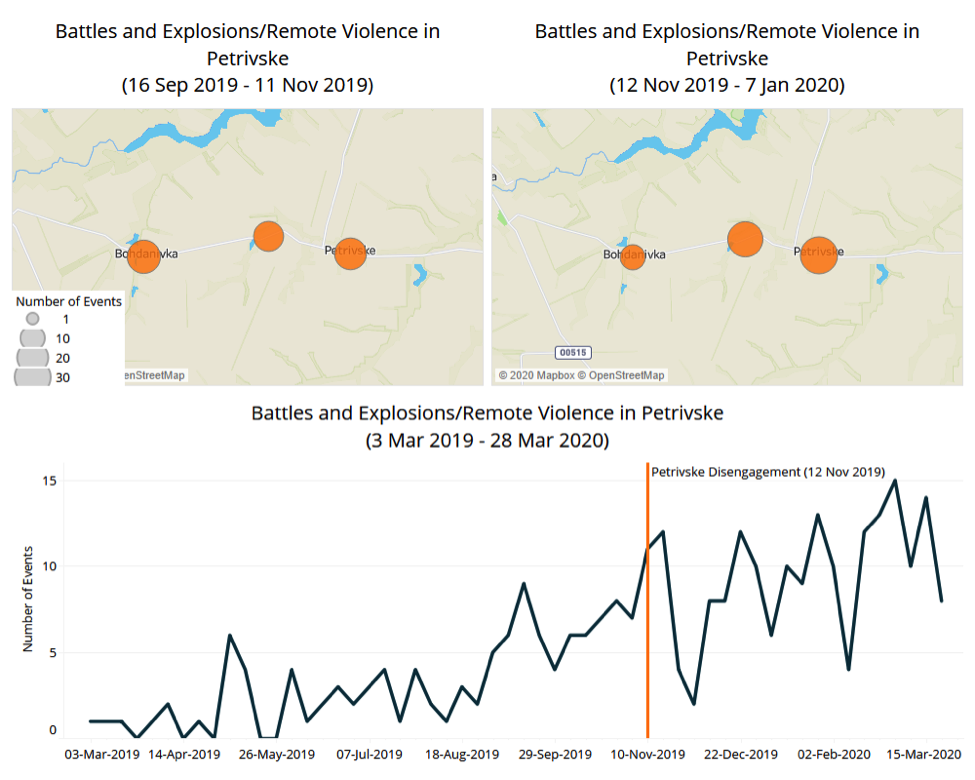

While ceasefires across the entire frontline have proven difficult to maintain, localized agreements could be more fruitful. The disengagement of forces agreements present a local approach to breaking up the fighting. They cover small areas, typically five to ten square kilometers, where military forces from both sides pull back one kilometer, dismantle their frontline defensive structures, and completely withdraw heavy weaponry from the area. These measures make it physically more difficult for the parties to engage in fighting, and due to the limited area, the agreement can be monitored in greater detail. In the fall of 2019, disengagement of forces agreements were implemented in the areas of Stanytsia Luhanska, Zolote, and Petrivske with mixed results (see map below).2

While disengagement of forces resulted in decreased fighting in two out of three cases, the effects did not spill over to other areas, where fighting continued unchanged. In none of the three cases did fighting stop completely. With each disengagement, both sides accused each other of breaking the ceasefire, re-occupying frontline positions and moving heavy weaponry back into the area.

Although temporary and incomplete, the ceasefires do result in short lulls that provide a brief respite to civilians and combatants. Agreements have been made at important times, such as the harvest period in June, the beginning of the school year in late August, and around the New Year and Orthodox Christmas celebrations. The disengagement of forces agreements allow civilians to cross frontlines at crucial points, and have created opportunities to repair bridges and clear minefields in the affected areas. Similarly, temporary and local ceasefires are routinely observed to allow for infrastructure repairs and demining. In this light, they represent positive steps, even if they do not result in significant decreases in the overall level of fighting.4

From an operational perspective, ceasefires also provide an opportunity to resupply, move weapons and equipment, and improve firing positions. The disengagement of forces in the Stanytsia Luhanska area, for example, allowed government troops to abandon an exposed frontline position and take up more secure positions separated by the Seversky Donets river (Radio Svoboda, 27 June 2019).

Ceasefire agreements also allow governments on both sides to claim political victories. After each agreement, the typical blame game ensues, in which each side accuses the other of violating the ceasefire first, perhaps in the hopes of whipping up national sentiments and gaining sympathy for their cause within the international community. While it is widely known that both parties violate the ceasefires, they still try to keep up the appearance of adherence. When an OSCE observation team arrives in a town, the inhabitants often breathe a sigh of relief, knowing that for that afternoon at least, the guns will stay silent.

The breakthrough implementation of the disengagement of forces agreement at Stanytsia Luhanska, Zolote, and Petrivske was likely propelled by Ukraininan President Volodymyr Zelensky’s ambition to restart peace talks – part of his 2019 campaign promise. Disengagement at the three areas, stipulated in the roadmap to the Minsk accords agreed on at the last Normandy summit in 2016, was marked as a prerequisite for holding a new Normandy summit (Interfax, 31 August 2019). While the disengagement agreements were poorly adhered to in practice, parties at the negotiating table did not make an issue of this and let the talks proceed, leading to the December 2019 Normandy summit agreements.

A breakthrough at the political level – necessary for any sustained ceasefire or progress on peace plans – seems unlikely to happen soon. Neither Ukraine nor Russia is willing to budge on key demands surrounding local elections in Donbas. Ukraine demands to have control over the border with Russia in the separatist-controlled areas before elections can proceed, to limit the risk of Russian interference. Russia has little incentive to move, and Germany and France do not seem willing to take further action to shift Russia’s incentives.

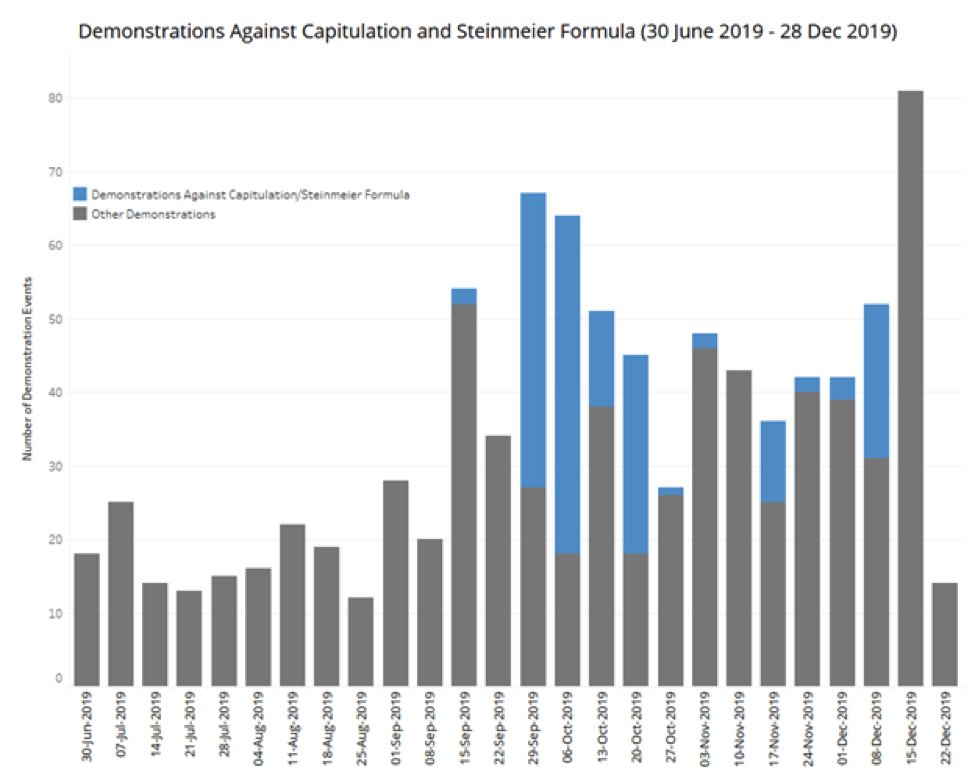

President Zelensky furthermore has to contend with a movement of nationalist actors and ordinary citizens that oppose the peace plan, which they view as ‘capitulation to Russia.’ Backed by political parties such as National Corps, nationalist actors can organize a significant number of demonstrations, as they did with rallies “Against capitulation” and the Steinmeier Formula in the run-up to the Trilateral Contact Group meeting on the Steinmeier plan in early October 2019 and the Normandy Summit in early December 2019 (see graph below).5 These actors have shown in the past that they are not a force to be dismissed (see this ACLED analysis). More recently, they have begun to voice opposition to any direct negotiations with the separatist rebels, after a new ‘Advisory Council’ to the TCG was proposed that would include DNR and LNR. According to critics, this would lead to implicit recognition of the DNR and LNR as ‘Ukrainian’ rebel groups rather than Russian proxies (ZN.UA, 13 March 2020). Furthermore, some of their leaders, like Andrei Biletsky of National Corps, advocate harder responses to ‘deter’ the rebel groups (Glavcom, 26 January 2020).

___________

1 Named after the first informal meeting held on 6 June 2014 during the 70th anniversary of the Allied invasion at Normandy.

2 ACLED codes event locations to the nearest town. The maps and graphs below therefore represent a slightly larger area than the exact disengagement area.

3 The Azov Battalion is one of the formerly independent volunteer units, now part of the National Guard.

4 For a critical note on the effect of disengagement on the local population, see Civic Monitoring, 23 February 2020.

5 In this graph, demonstrations ‘against capitulation and the Steinmeier Formula’ are manually highlighted based on ACLED Event Notes referring to these demonstration issues.