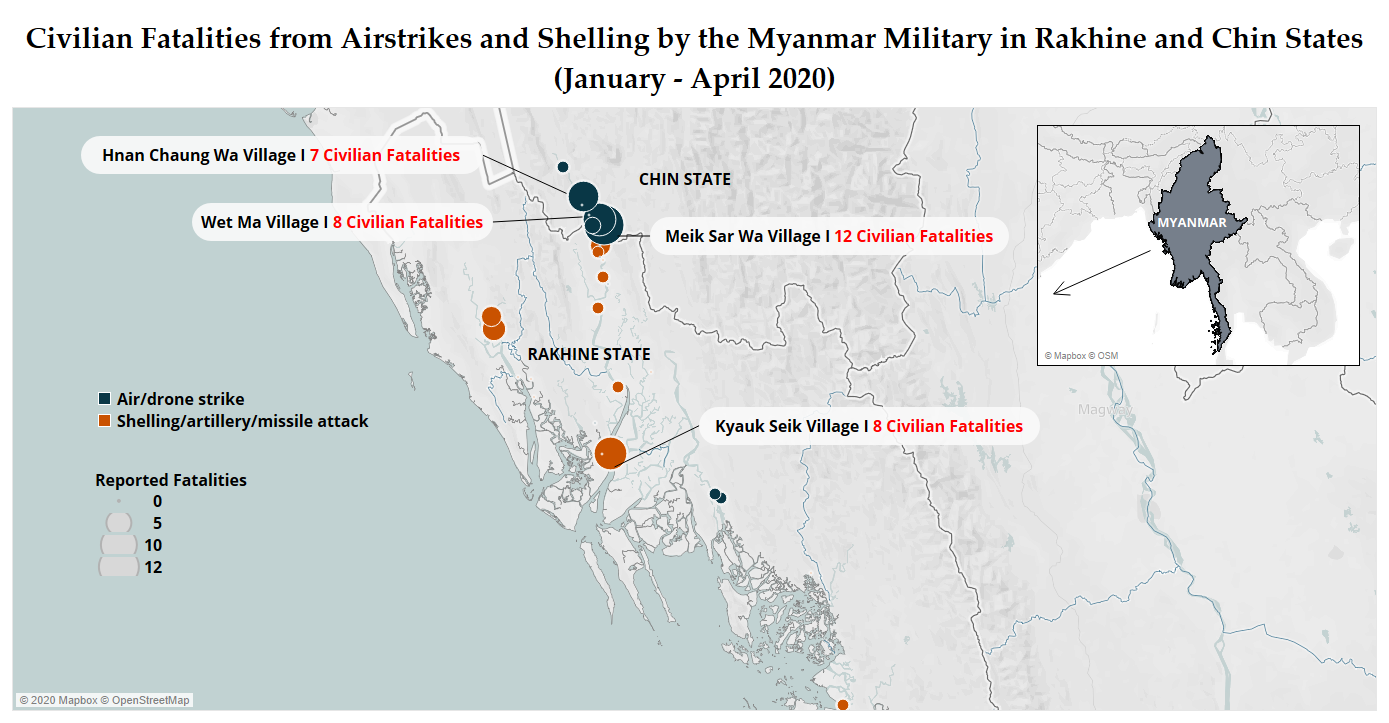

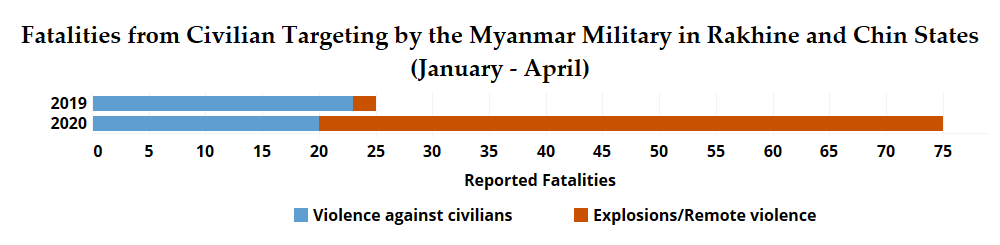

On the same day the United Nations Secretary-General called for a global ceasefire amid the coronavirus pandemic, the Myanmar military designated the United League of Arakan/Arakan Army (ULA/AA) — an ethnic Rakhine armed group fighting for greater autonomy in Rakhine state — as a “terrorist” group. Authorities then set about detaining journalists and blocking online access to media outlets reporting on the conflict. The military has ramped up its campaign of airstrikes and shelling in the region since the start of 2020, leading to a spike in reported civilian fatalities (see figure below). At the current rate, 2020 is set to become a deadlier year for civilians in Myanmar’s conflict zones than 2019.

Increased Civilian Fatalities

Increased Civilian Fatalities

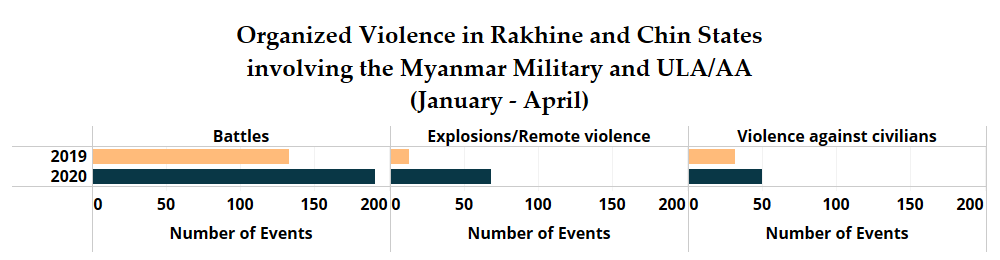

From January to April 2020, organized violence in Rakhine state and neighboring Chin state involving the military and the ULA/AA has increased by 74% relative to the same period last year (see figure below).

Despite mounting civilian casualties, the military has rejected calls for a ceasefire. While the Brotherhood Alliance, of which the ULA/AA is a part, announced an extension of its own unilateral ceasefire — framing the extension as a response to the coronavirus pandemic — this has had little impact on the conflict.

While the conflict in Rakhine and Chin states has attracted the most attention, the military has been using similar tactics in other parts of the country. Notably, since the beginning of the year, there has been a marked increase in the number of shelling events carried out by the military in Kayin state. The military has shelled areas in Hpapun district under the control of the Karen National Union/Karen National Liberation Army (KNU/KNLA) (Karen Peace Support Network, 19 April 2020). Tensions in the region are high as the military continues a road construction project which is viewed by the KNU/KNLA to be in violation of the 2015 Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) to which it is a signatory. While civilian fatalities from shelling in Kayin are not as high as in Rakhine and Chin, the violence has displaced villagers and further inflamed tensions.

More recently, the military has pressured the KNU/KNLA to halt its efforts to respond to the coronavirus, claiming the movement of KNU/KNLA troops violates the NCA (New Mandala, 30 April 2020). Similarly, another signatory to the NCA, the Restoration Council of Shan State/Shan State Army-South (RCSS/SSA-S), has clashed with the military while affiliated medics were carrying out coronavirus awareness activities. Both the KNU/KNLA and RCSS/SSA-S, among other ethnic armed groups, have appealed to the military to announce a unilateral nationwide ceasefire in order to focus on the pandemic, to little avail (Frontier Myanmar, 15 April 2020).

Information Blackout

The current conflict in Rakhine and Chin states is aggravated by the lack of access to the region and the government’s ongoing suppression of independent reporting. An internet shutdown covering several townships in Rakhine state and Paletwa township in Chin state has been in effect since June 2019. Activists who protested the shutdown have been charged under a law restricting peaceful assembly for failing to request permission to demonstrate (Reuters, 24 February 2020).

In addition to the internet shutdown, the designation of the ULA/AA as “terrorists” led to the swift repression of journalists covering the conflict (Radio Free Asia, 30 April 2020). The editor of a Mandalay-based media outlet was detained after publishing an interview with ULA/AA leaders. Further, internet companies in the country have been ordered to stop allowing access to Rakhine-based media outlets reporting on the conflict (Frontier Myanmar, 27 March 2020). Notably, many lawmakers from Rakhine state have found themselves targeted for harassment for sharing information with the media about the conflict in their constituencies (Network Media Group, 22 April 2020). The crackdown on the media creates an environment ripe for the continued abuse of civilians and hinders efforts at coronavirus prevention.

Broken Trust

As the conflict escalates, the pandemic has allowed the military to further consolidate power by forming its own coronavirus task force in parallel to the one established by the National League for Democracy (NLD) government (Asia Times, 2 April 2020). At the same time, the NLD government has promoted the military’s narrative that the Rakhine rebels are “terrorists.” The NLD leader and State Counsellor, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, released a statement in April in which she praised the military’s actions in Rakhine and Chin states (State Counsellor, 21 April 2020).

Suu Kyi’s statement dismayed ethnic leaders who previously viewed the State Counsellor as sympathetic to their calls for autonomy (Irrawaddy, 23 April 2020). The move deepens the rift between the NLD and ethnic minority populations in the run-up to the 2020 general elections. While a committee was established in late April to coordinate coronavirus-related efforts with ethnic armed groups, it remains to be seen whether it will be effective (Irrawaddy, 28 April 2020).

Despite the military and government’s efforts to paint the ULA/AA as “terrorists,” locally, the group has seized the narrative that they are fighting on behalf of the Rakhine people. Failing to recognize the need for a sincere political dialogue with all of Myanmar’s ethnic groups will only lead to further bloodshed, of which civilians increasingly bear the brunt. Myanmar’s many ethnic conflicts cannot be settled on the battlefield.