On 23 March, UN Secretary-General António Guterres called for a global coronavirus ceasefire (UN News, 23 March 2019). The truce would allow pandemic responses to be carried out in areas that are usually too dangerous for medical personnel to access due to ongoing conflict, and could also create opportunities for negotiations between belligerents.

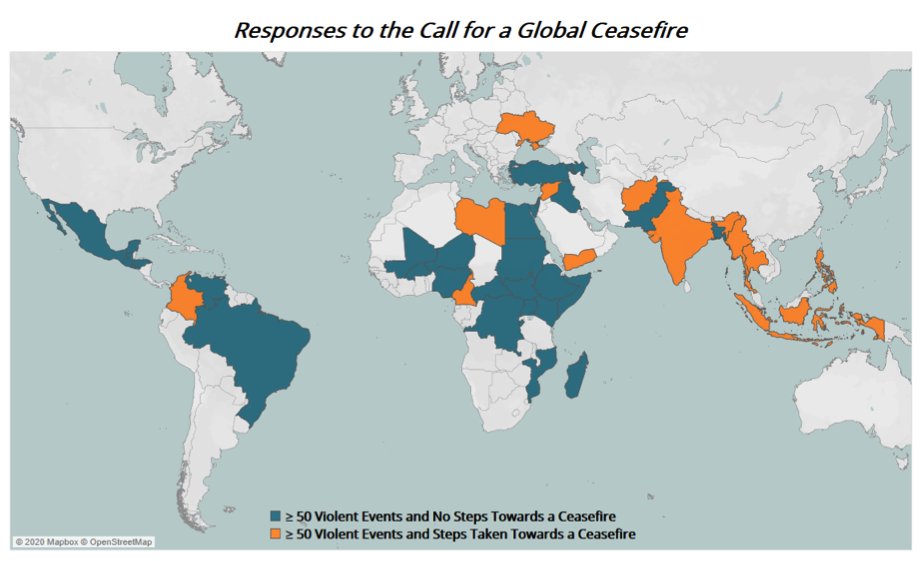

Unfortunately, the call for a global ceasefire has largely fallen on deaf ears. Out of 43 countries where there have been at least 50 reported events of organized violence this year (see figure below),1A threshold of 50 events was selected here as it is useful in identifying countries in which significant armed, organized violence has been reported, yet is not prohibitively high as to exclude many of the countries where steps have been taken toward ceasefires. only 10 saw actors “welcome” the call, declare a unilateral ceasefire, or establish a mutual ceasefire agreement (these 10 are included among the countries highlighted orange in the map below, alongside Libya and Thailand, where actors took steps toward ceasefires unrelated to the UN appeal).2The statements in Libya “welcoming” a ceasefire happened before the UN call. The Barisan Revolusi Nasional Melayu Patani (BRN) in Thailand does not make reference to the UN in its statement announcing it would “stop activities.” These two cases are reviewed here as examples of conflict actors reacting to the coronavirus, but they do not constitute formal responses to the UN’s call for a global ceasefire. Of the other 31 countries, not only did conflict actors fail to take steps to meet the call, many actually increased rates of organized violence, such as in Mexico, Iraq, Mozambique, and Brazil. While there have been some positive responses, most are simply statements of support with no commitment to action. Those groups that have taken action have done so unilaterally, and with varying levels of commitment. For the rare actors that have managed to establish bilateral ceasefires, both parties have subsequently struggled to extend the agreements past a short window. In general, the call for a global ceasefire has not had the desired result. In conflicts where ACLED identifies a reduction in violence, there is often an alternative explanation for the decrease.

The following analysis provides brief overviews of conflicts in which participant actors have responded in some form to the UN call for a global ceasefire.

Afghanistan

On 1 April, the Taliban announced that it is prepared to stop fighting in areas under its control that are impacted by the coronavirus, but did not agree to a full ceasefire with the Afghan government (Associated Press, 1 April 2020). Taliban members have reportedly been seen wearing medical gear and providing workshops on preventing the spread of the virus (Al Jazeera, 6 April 2020). The pandemic provides an opportunity for the Taliban to increase its legitimacy in the eyes of the local population in a governance role spearheading the fight against the coronavirus, and so these actions further its goals. It is in the group’s interest to avoid an outright ceasefire; this would provide relief to the Afghan government, which would also allow them to spearhead this effort instead. Rather, continued fighting with the Afghan government during a vulnerable time for the state gives the Taliban further advantage during the ongoing negotiations.

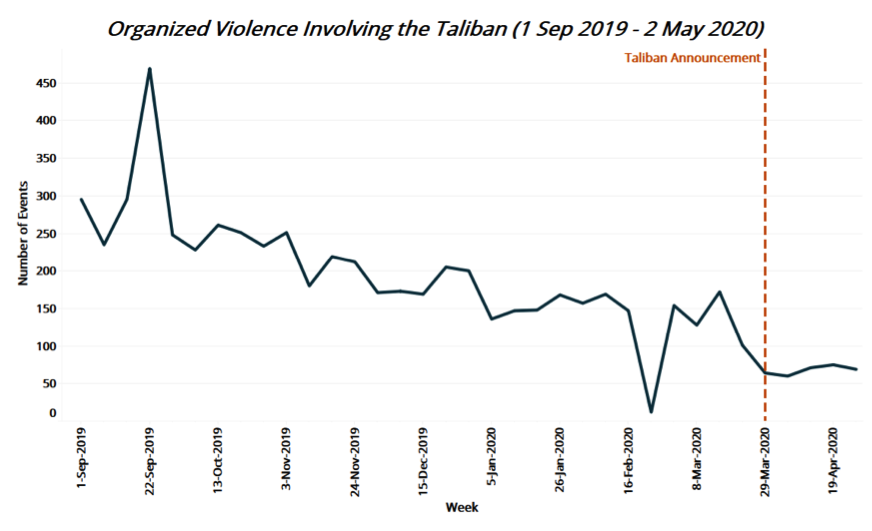

Since the Taliban announcement on 1 April, the group has continued to engage in violence in areas with confirmed cases of COVID-19 (see graph below), but not in areas that are already under its control. Overall, while organized violence involving the Taliban has remained relatively low during April, this is part of a larger decrease in violence that began before the coronavirus outbreak, in the lead up to the agreement made with the US in late February. On 23 April, the Taliban rejected President Ashraf Ghani’s call for a ceasefire during Ramadan, indicating that the group intends to continue to pressure the beleaguered Afghan state as negotiations continue (Al Jazeera, 24 April 2020).

For more information, see this recent CDT Spotlight on Taliban activity in Afghanistan.

Cameroon

On 22 March, the Southern Cameroons Defense Force (SOCADEF) declared a unilateral ceasefire for 14 days to allow coronavirus aid to enter its area of control (BBC, 26 March 2020). However, the largest Ambazonian separatist group, the Ambazonia Defense Forces, has declared that it will not observe a ceasefire, and the Government of Cameroon has not announced any plans for a truce (RFI, 27 March 2020). While the ceasefire in Cameroon only includes one actor, and not even the largest Ambazonian separatist group, the UN has described SOCADEF’s ceasefire as an example of a successful response to their call (UN, 2 April 2020).

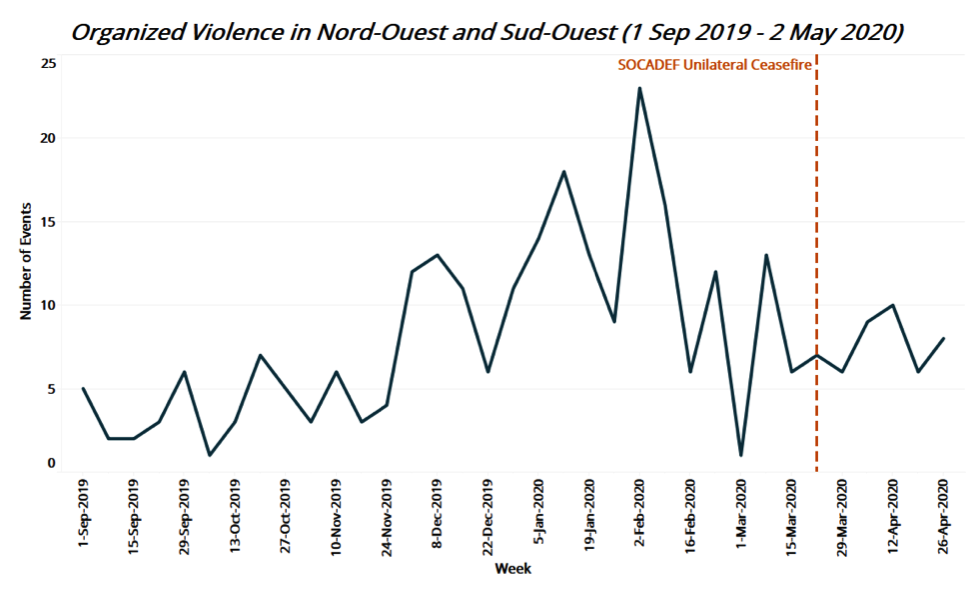

While organized violence in the mostly Anglophone regions of North-West and South-West has remained lower than the 2020 peak in early February (see graph below), this is part of a longer trend of reduced violence in the region that started before the SOCADEF ceasefire. Overall, organized violence in North-West and South-West has continued since SOCADEF’s announcement, demonstrating the limited impact of a ceasefire made by only one group among many. In the absence of a ceasefire agreement between the Ambazonia Defense Forces and the military, Cameroon is unlikely to see a sustained drop in violence.

For more, see the ACLED report entitled Continued Clashes between the Government and Anglophone Separatists in Cameroon Put Civilians at Risk.

Colombia

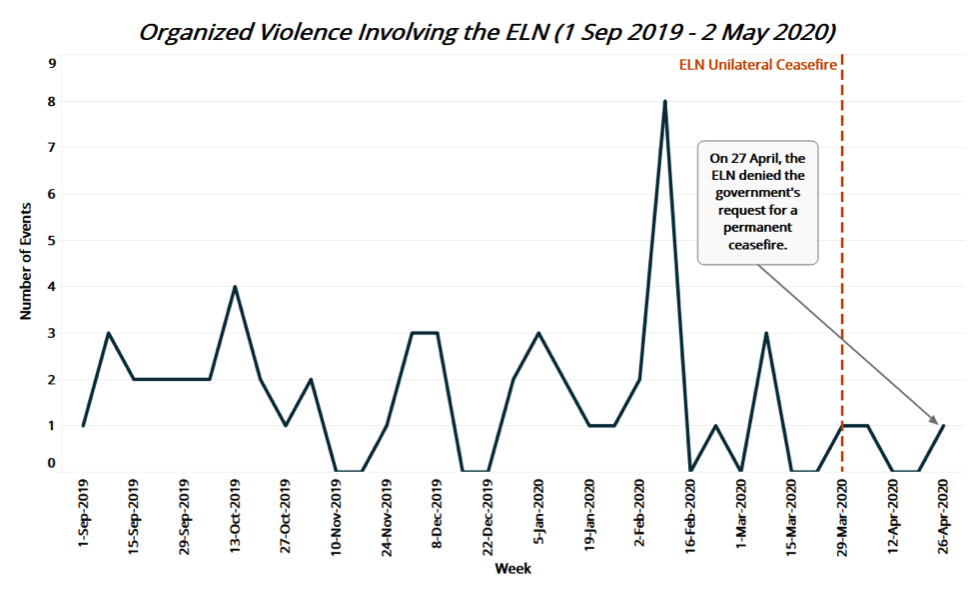

On 29 March, shortly after the Colombian government appointed two former National Liberation Army (ELN) members to serve as peace mediators, the ELN called for a month-long unilateral ceasefire beginning on 1 April (Colombia Reports, 30 March 2020). The ELN statement made clear that the group would continue to defend itself in the event it was attacked by government forces or by other armed groups (Colombia Reports, 30 March 2020). The near-simultaneous statements initially generated cautious optimism about renewed negotiations.

The ELN has seemingly upheld its commitment to a unilateral ceasefire during the month of April — having only been involved in one violent event since 1 April: a battle between ELN and Gulf Clan forces on 5 April (see graph below). However, hope for a lasting peace is now fading. The ELN has since denied the government’s request for a permanent ceasefire, throwing into question how long the pause in violence will continue (EFE News, 27 April 2020).

For more, see the Colombia chapter of ACLED’s report entitled Disorder in Latin America: 10 Crises in 2019.

India

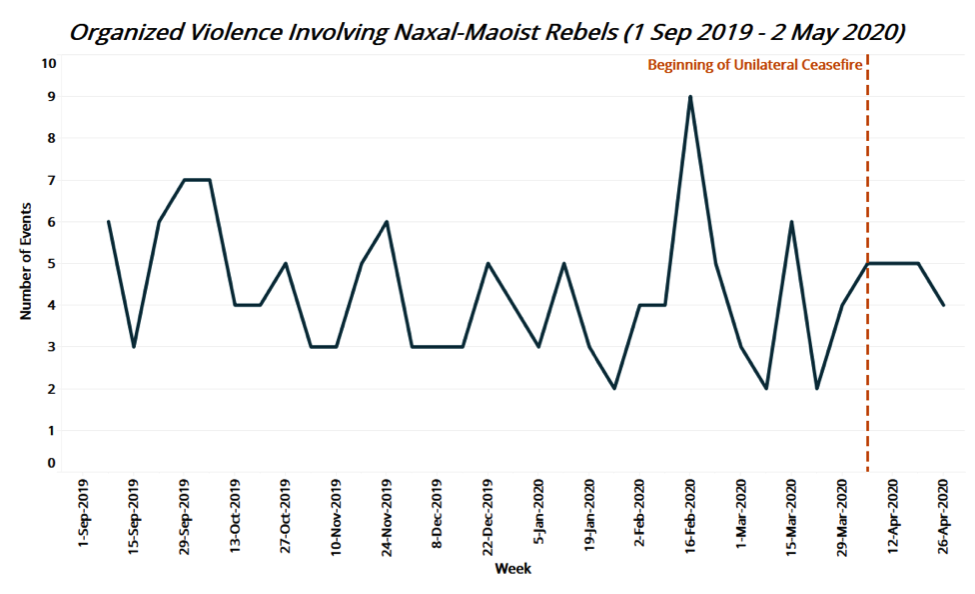

On 5 April, two weeks after killing 17 Central Reserve Police Force personnel, the Communist Party of India (CPI) (Maoist) announced a unilateral ceasefire in order to better contain the coronavirus, giving the government five days to respond to the offer (Times of India, 7 April 2020). The national government and local officials have ignored the Maoist announcement (Deccan Chronicle, 19 April 2020).

Organized violence involving Naxal-Maoist rebels has remained relatively consistent since the CPI (Maoist) announced its unilateral ceasefire, as seen in the graph below. Naxal-Maoist rebels have continued to engage in various forms of violence against civilians, including destruction of property and abductions of suspected “police informers.” With reports of local government patrols pulling back to bases as part of the national curfew, Naxal-Maoist rebels may be looking to take advantage of the reduced military presence by regaining lost territory or preparing for renewed conflict after the pandemic (The Print, 20 April 2020).

For more, see ACLED’s recent CDT Spotlight on India assessing the ongoing concurrent conflicts in the country.

Indonesia

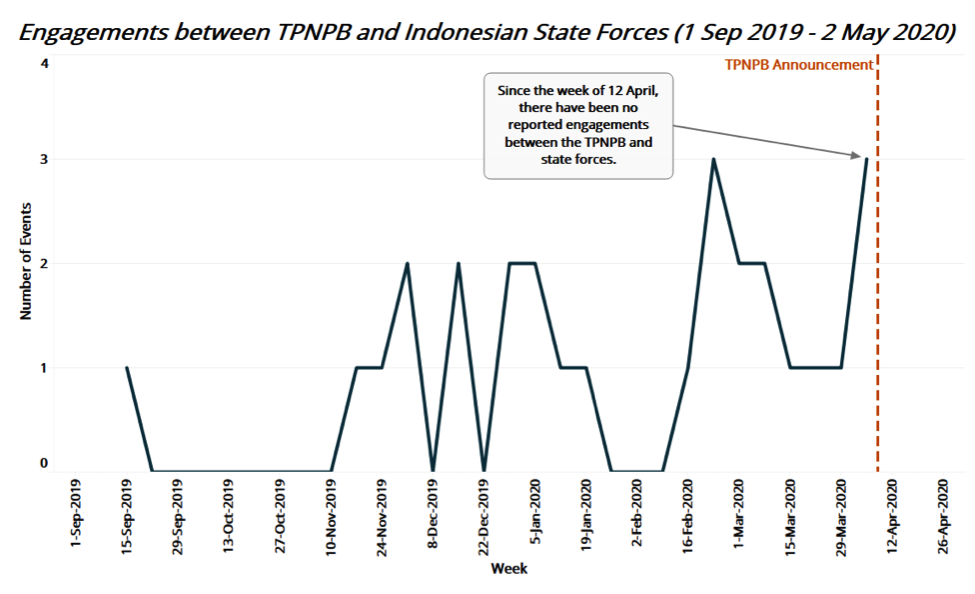

On 8 April, the West Papua National Liberation Army (TPNPB) chairperson, Jeffrey Bomanak, released a written statement announcing that the group sought a ceasefire with the Indonesian government in light of the UN’s call for a ceasefire (Asia Pacific Report, 11 April 2020). The offer came just over a week after an attack by the TPNPB on the Freeport Mining Company’s residential housing area in Papua province, in which a New Zealander employee was killed and six others were wounded (Asia Times, 1 April 2020). So far, there does not seem to be a government response to the TPNBP’s statement.

Encounters between TPNPB and government forces, while infrequent, have increased in early 2020 compared to late 2019, as can be seen in the graph below. Since the week of 26 April, ACLED records no TPNPB activity. Although it is not uncommon for there to be weeks with no reported events involving the TPNPB, this does represent a pause in activity following the ceasefire announcement.

For more, see the ACLED infographic entitled Elections in Indonesia: Implications for West Papua.

Libya

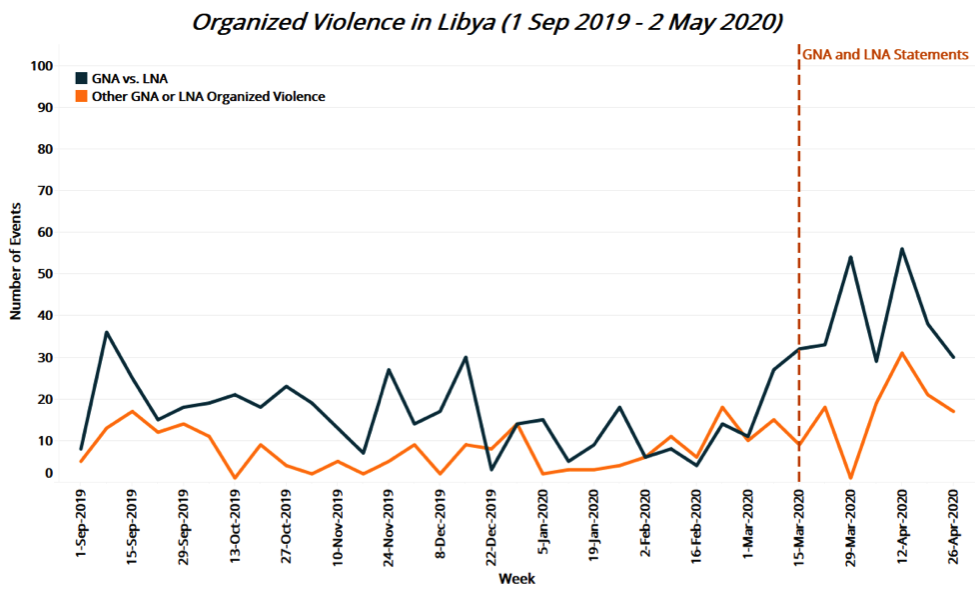

Shortly before the UN appeal, the Government of National Accord (GNA) and the Libyan National Army (LNA) both “welcomed” international calls for a humanitarian ceasefire in Libya to address the coronavirus on 18 and 21 March, respectively. Though, neither party agreed to a formal ceasefire (UN News, 21 March 2020). The United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL) welcomed the statements and urged both parties to adopt the draft ceasefire agreement reached on 23 February in Geneva (UNSMIL, 21 March 2020). Predictably, verbal support for a ceasefire did not translate to reduced violence on the ground, as seen in the graph below.

During the week of 15 March, when both GNA and LNA announcements were made, fighting plateaued but did not decrease (see navy line in graph above). In subsequent weeks, engagements between GNA and LNA forces — as well as all other organized violence involving either actor, including attacks on civilians and clashes with other armed groups — have steadily risen (see orange line in graph above). Increasing reports of actors shelling hospitals are especially troubling as civilians must now contend with both violence and the risks posed by the coronavirus (New York Times, 13 April 2020). The escalation in Libya illustrates how armed groups may verbally “welcome” a ceasefire as an easy public relations move, in the absence of any real willingness to reduce violence.

For more information, see ACLED’s recent CDT Spotlight on Libya mapping the escalating fighting despite the spread of coronavirus.

Myanmar

On the same day as the UN appeal on 23 March, the Myanmar military designated the United League of Arakan/Arakan Army (ULA/AA) a “terrorist” group. Shortly afterwards, the military moved to crackdown on media outlets covering the conflict. Anyone found to be in contact with the ULA/AA faces life in prison (Asia Times, 2 April 2020). The ongoing internet blackout in several townships in Rakhine and southern Chin states — coupled with the coronavirus pandemic — has severely restricted open reporting on the violence.

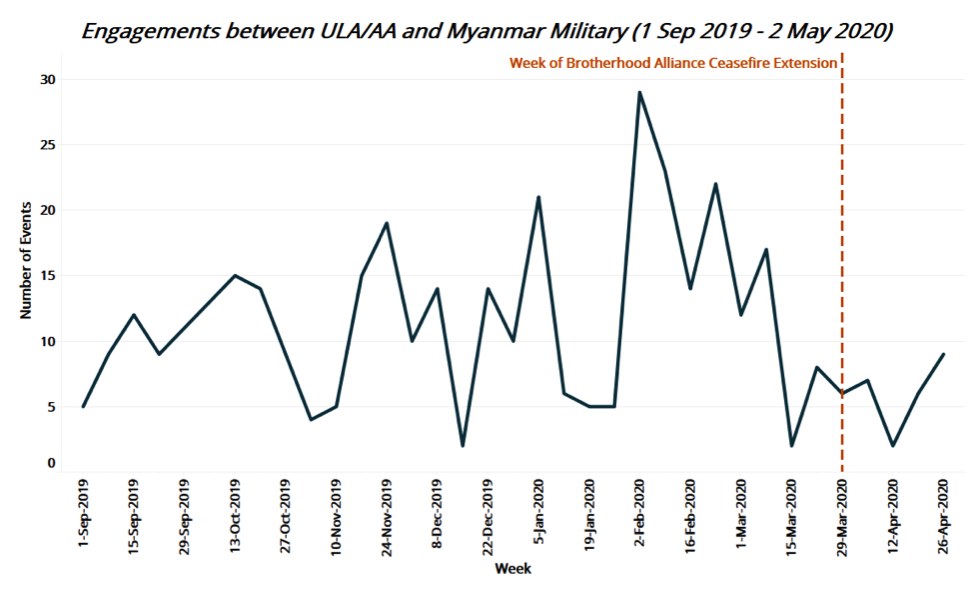

While the military has declined to consider a ceasefire with the ULA/AA, the Brotherhood Alliance, which includes the ULA/AA, declared an extension of their unilateral ceasefire on 1 April, framing it as a response to the pandemic (Arakan Army, 1 April 2020). Other ethnic armed organizations in the country have also called on the military to announce a unilateral nationwide ceasefire, so far to no avail. While clashes with the ULA/AA appear to have declined slightly in recent weeks during the Burmese new year (as seen in the graph below), the military has increased air strikes and shelling of ULA/AA positions and villages, resulting in a high number of civilian fatalities. On 9 May, the military announced a unilateral ceasefire in parts of the country but excluded Rakhine State, increasing the likelihood of continued clashes with the ULA/AA (The Irrawaddy, 11 May 2020).

For more, see the recent ACLED report entitled Coronavirus Cover: Myanmar Civilians Under Fire.

Philippines

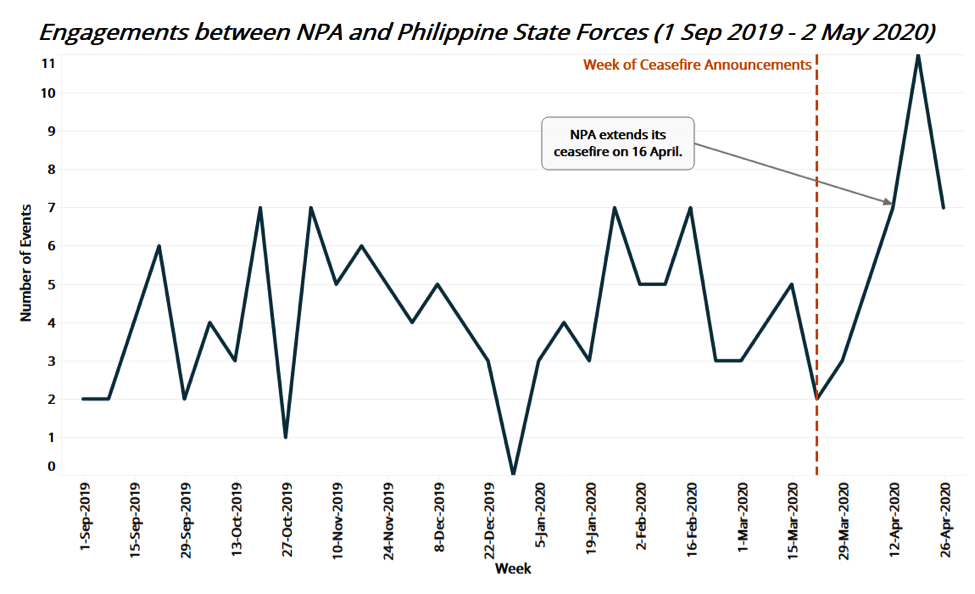

In response to the UN appeal, the Government of the Philippines and the communist New People’s Army (NPA) each enacted unilateral ceasefires, on 18 March and 26 March respectively (The Diplomat, 25 March 2020). Despite the dual ceasefires, there are consistent reports of continued fighting, which both sides have been quick to blame on the other. On 16 April, the NPA extended its unilateral ceasefire through 30 April, but the government, citing continued attacks from NPA forces, allowed its ceasefire to expire (Rappler, 16 April 2020; Inquirer.net, 19 April 2020). The graph below depicts engagements between the NPA and Philippine state forces.

The now one-sided ceasefire makes a reduction in organized violence less likely. While there was a drop in violence between the two groups during the week of 22 March when the ceasefires were first announced, fighting between state forces and the NPA has continued to increase in the weeks since then. Organized violence has now surpassed pre-ceasefire levels; the highest levels of the year were reported during the week of 19 April (see graph above).

For more, see ACLED’s recent CDT Spotlight on the Philippines assessing the initial impact of the ceasefires.

Syria

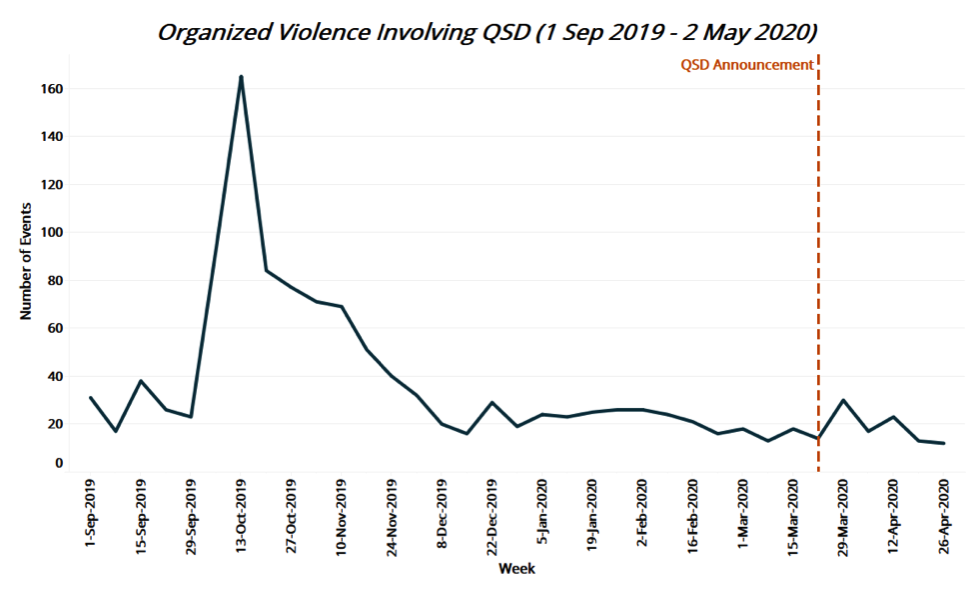

On 24 March, the Syrian Democratic Forces (QSD) announced that they would cease military activity, except defensive actions, to facilitate responses to the coronavirus (Al-Monitor, 24 March 2020). The QSD called on other parties to agree to a humanitarian ceasefire, but no other actor has indicated plans to reduce violence in light of the pandemic.

Despite the QSD’s announcement, its military operations have not come to a complete stop. QSD activity has remained low, yet steady, since early December 2019 (see graph below). QSD involvement in organized violence is similar to levels seen before the Turkish offensive in northern Syria, beginning in October 2019 (see graph below). With much of the violence currently concentrated in the northwest, and Turkey accusing Syrian forces of breaking the 5 March ceasefire established prior to the pandemic,3On 5 March, Russia and Turkey reached a ceasefire agreement in northwest Syria near Idleb. Under the agreement, Russian and Turkish forces carry out joint patrols of the highway linking west and east Syria (Reuters, 13 March 2020). the tenuous truce in Idleb is increasingly at risk (Reuters, 20 April 2020).

For more, see the latest update to ACLED’s State of Syria series mapping changes in territorial control.

Thailand

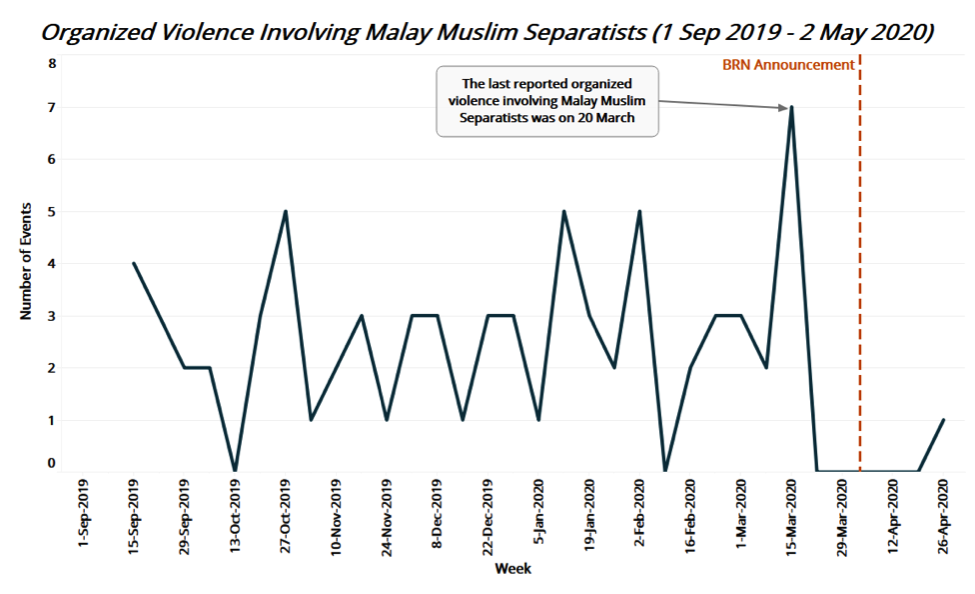

On 17 March, the Barisan Revolusi Nasional Melayu Patani (BRN), the main separatist group in Thailand’s deep south, bombed a government meeting held to discuss the coronavirus pandemic (Associated Press, 17 March 2020). Two weeks later, on 3 April, the BRN released a statement saying it would “cease activity” as long as the group was not attacked by government forces. The deep south region has seen high numbers of coronavirus cases. However, the BRN announcement did not explicitly endorse a ceasefire, nor did it reference the UN’s call for a global ceasefire (Asia Times, 6 April 2020). The Thai military has largely ignored the BRN’s statement, and has dismissed the offer as “irrelevant” (Benar News, 16 April 2020).

Following the BRN announcement, separatist violence has decreased, as seen in the graph below. From 20 March through 29 April, there was no violence reported involving any Malay Muslim separatist group. However, on 30 April, Thai police attempted to arrest three BRN members suspected of planning an attack during the month of Ramadan. The separatists opened fire on police during the raid, and all three suspects were killed in the resulting shootout (Benar News, 30 April 2020). This was the first clash between state forces and the BRN since the group’s announcement in March. It remains to be seen whether the temporary pause in separatist violence will continue in the wake of this event.

For more, see the ACLED infographic entitled Elections in Thailand: Implications for the Deep South.

Ukraine

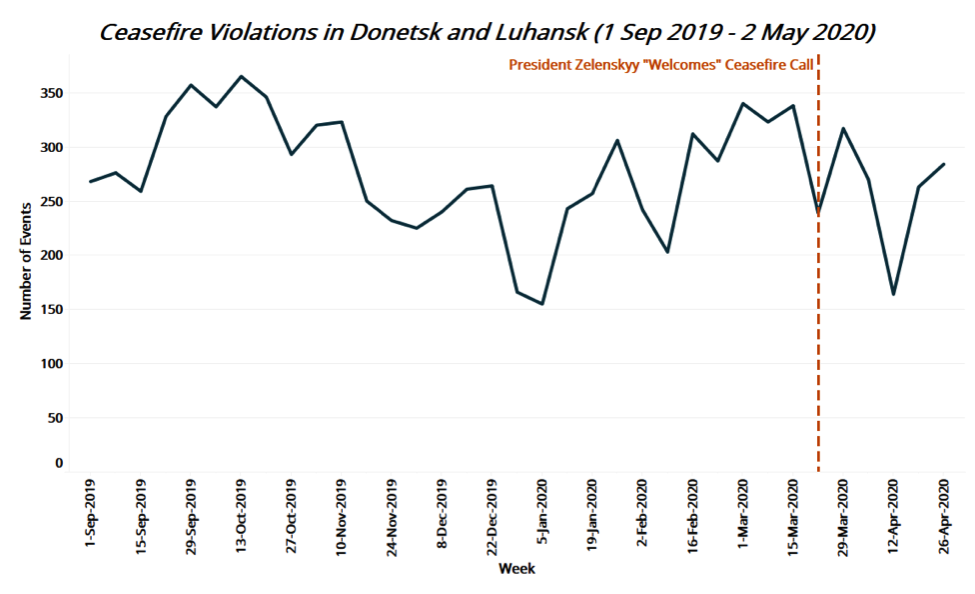

On 24 March, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy “welcomed” the call for a global coronavirus ceasefire, and on 26 March Ukraine used OSCE channels to ask Russia to ensure a full ceasefire (UN, 2 April 2020; UNIAN, 26 March 2020). The Russian Foreign Ministry released a statement on 24 March supporting the UN appeal, but excluded Ukraine from the list of conflicts mentioned in the announcement (The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, 24 March 2020).

Ceasefire violations in Ukraine have continued since President Zelenskyy “welcomed” the call for a coronavirus truce (see graph below). While there was a significant decrease during the week of 12 April, this is likely related to the prisoner exchange on 16 April rather than in response to the president’s “welcoming” (Euromaidan Press, 16 April 2020). Ceasefire violations increased the following two weeks (weeks of 19 April and 26 April). There have been several ceasefire agreements since the start of the conflict in Ukraine, none of which have had a lasting impact. It is therefore unsurprising that a “welcoming” by just one party to the conflict has not led to a serious reduction in violence.

For more, see the ACLED report entitled Donbas: Where the Guns Do Not Stay Silent.

Yemen

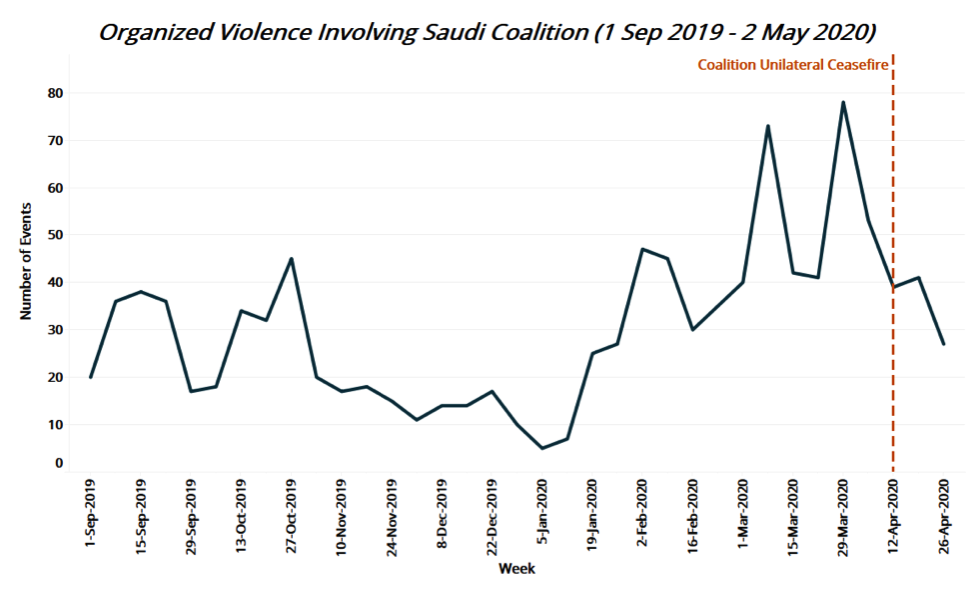

On 9 April, the military coalition led by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) commenced a two-week long unilateral ceasefire in Yemen with the stated goal of avoiding a coronavirus outbreak (Associated Press, 9 April 2020). Houthi forces said they would not abide by a ceasefire, demanding that the coalition lift its blockade of Yemen before any truce would be negotiated (Associated Press, 9 April 2020).

Despite a slight decrease in organized violence involving coalition forces during the week the ceasefire was announced, fighting has continued (see graph below). During the week of 19 April, the same week coalition forces announced an extension to the ceasefire, violence involving coalition forces increased (Reuters, 24 April 2020). While coalition air raids have continued at lower levels, the Yemen Data Project still records hundreds of airstrikes during the ceasefire period, including more than 80 through the third week of the truce (Yemen Data Project, 2 May 2020).4 The Yemen Data Project is an ACLED partner. An effective coronavirus response in Yemen will require a durable ceasefire that both coalition and Houthi forces can agree to in order to reduce violence.

For more information, see this recent CDT Spotlight on Yemen.