Although often hailed as a “democratic exception” in the region because of its successful democratic transition following the revolution in 2011 (New York Times, 27 October 2015; The New Arab, 1 July 2016; Inter Press Service, 17 December 2018), Tunisia has faced several challenges in addressing the socioeconomic grievances of its population. The slow economic recovery has led to discontent among Tunisians who blame the government for the lack of economic growth and the high unemployment rate (Atlantic Council, 12 February 2015). The fallout from the coronavirus outbreak has exacerbated the economic crisis, leading to a revival of demonstration activity across Tunisia.

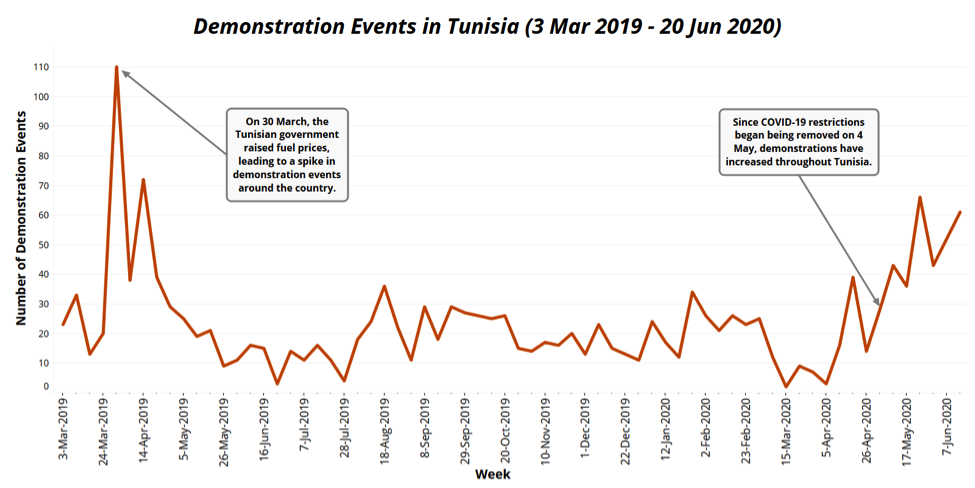

In recent years, Tunisia has consistently registered some of the highest demonstration levels in Africa. While the coronavirus pandemic initially led to a drop in the number of demonstrations, ACLED records a significant increase in peaceful protest events across the country beginning in April 2020 — hitting their highest levels since early April 2019 when nationwide demonstrations against a fuel price hike spiked (see figure below). After the government eased coronavirus-related restrictions at the start of May (BBC, 4 May 2020), the number of demonstrations more than doubled compared to April, and activity remains on the rise thus far in June.

Who Are the Demonstrators and What Are Their Demands?

Most of the recent demonstrations revolve around socioeconomic issues and the government’s failure to address the inequalities that led to the 2011 Tunisian revolution and several other rounds of demonstration activity over the nine years since then. Tunisia is one of the poorest countries in the Middle East and North Africa region (Tunisie Numerique, 3 February 2020). The GDP growth has fallen considerably in recent years, especially compared to pre-revolution rates (Word Bank, 2018). Over 15% of Tunisians (nearly two million out of the 11 million population) live below the poverty line (World Bank, 2015), with most of them residing in marginalized inland provinces (Brookings, 14 February 2019).

In October 2019, the election of President Kais Saied, an independent candidate, brought hope to many Tunisians that the ailing economy would be fixed, with Saied himself calling it a “new revolution” (The Economist, 17 October 2019). However, this optimism began to fade amid a months-long political crisis prompted by the failure to form a government (Al Jazeera, 26 February 2020) as well as the economic fallout following the coronavirus lockdown.

The spread of the coronavirus to Tunisia and the government’s total lockdown, including the closure of borders and the imposition of a nationwide curfew, brought the country’s economy to a near halt, particularly impacting the informal sector, tourism, and the industrial sector (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 29 April 2020). This has worsened the country’s already sluggish economy, with the International Monetary Fund predicting a 4% contraction in 2020 (10 April 2020). 60% of employees on leave because of the coronavirus stated that they no longer received any remuneration; this number stands at almost 80% for those in the two lowest income quantiles (National Institute of Statistics, 28 May 2020). The country’s low-income communities have thus borne the brunt of the pandemic’s economic fallout.

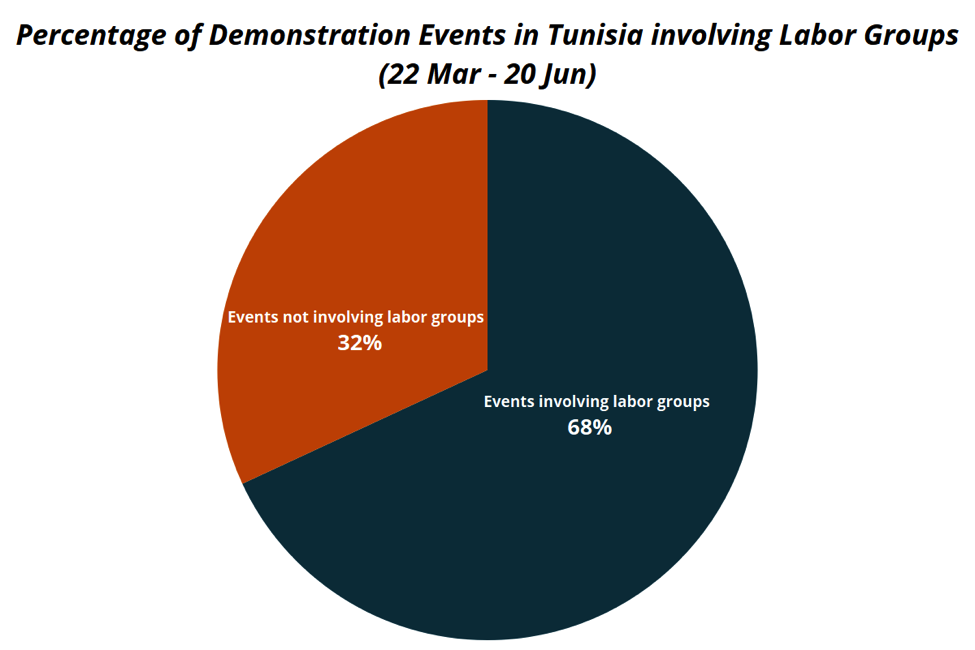

The recent wave of demonstration activity has swept across most of the country, showing that the pandemic’s impact extends beyond the traditional divide between Tunisia’s developed coastal regions and the impoverished hinterland (Carnegie Middle East Center, 19 February 2020). The figure below depicts how most of these events are led by labor groups (in navy) whose demands have been heightened by the economic impacts of COVID-19.

Unemployment remains the main impetus behind the majority of demonstrations during this period. Since the 2011 revolution, the unemployment rate has stayed in the range of 15-18% (World Bank, 1 March 2020), with the rate being higher among the youth (36%) and graduates (28%) (World Bank, 1 October 2019; 1 March 2020).

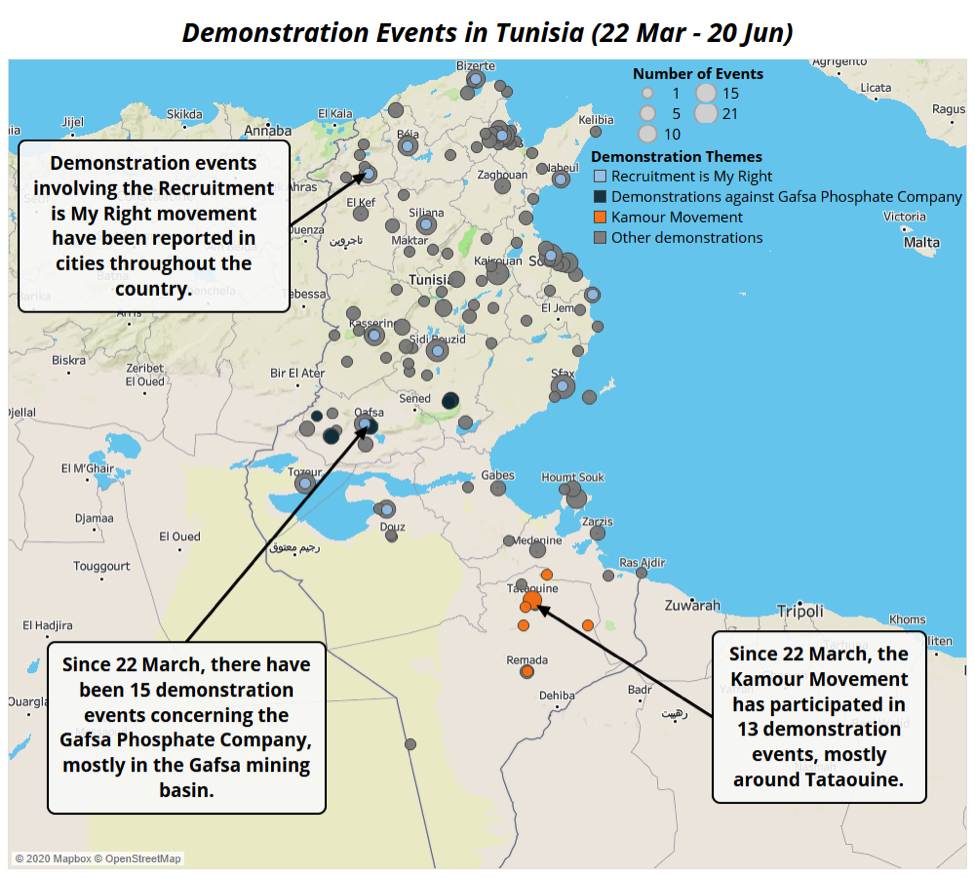

Over the past two decades, there have been numerous demonstrations in the country’s energy production sites by local residents who are asking to benefit from the opportunities at these sites. Protesters began holding multiple sit-ins at the mines of the state-run Gafsa Phosphate Company (CPG) in May 2020 to ask for job opportunities (Reuters, 28 May 2020). The mining towns in Gafsa were the epicenter of economic and employment demonstrations against ousted President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali in the years leading up to the 2011 uprising. In 2008, a six-month mass revolt against corrupt hiring practices at the Gafsa mines resulted in at least three fatalities and many injuries (New York Times, 13 May 2014; Amnesty International, 4 October 2018). The mining basin remains one of the main sites of demonstration activity in the Gafsa governorate. Demonstrators have repeatedly disrupted mine operations, sometimes for several months straight (Reuters, 21 March 2018).

Moreover, the Kamour Movement, which started in April 2017 in El Kamour oilfield near the town of Tataouine to demand employment (Reuters, 16 June 2017; Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 8 August 2017), has resurged again, despite reaching an agreement with the government three years ago (Aljazeera, 22 June 2020; The National, 25 June 2020). The movement has held several demonstrations calling for the implementation of the employment provisions in the agreement.

In addition to these existing labor movements, a new movement emerged in January 2020 called the National Coordination of Recruitment Is My Right. The movement includes unemployed youth demanding the adoption of a basic law to provide urgent employment opportunities for those who have been without work for more than 10 years. On 14 May, the government passed Circular No. 16 on the preparation of the government budget for the year 2021. This includes austerity measures to confront the negative repercussions of the economic and financial crisis resulting from the outbreak of the coronavirus (DCAF, 14 May 2020). In response, the National Coordination of Recruitment Is My Right organized several demonstrations across the country to denounce the measure, especially the suspension of employment in the public sector (Alikhbaria Attounsia, 28 May 2020). The map below depicts the locations of demonstrations associated with all of these movements.

In light of the current pandemic, different labor groups have also taken to the streets to demand the payment of their salaries without any deductions during the lockdown and to ask for government financial assistance as well as public subsidies to deal with the economic impact of the health crisis. Several groups of public workers, including cleaning workers and police, have demonstrated to bring attention to unsafe working conditions and to demand protection (Assabah News, 13 April 2020; Assarih, 8 May 2020; Radio Sabra FM, 14 May 2020). Health workers have also held several demonstrations, first demanding protective equipment against the coronavirus and later calling for the enactment of a law to provide protections to health workers. On 28 May, they organized protests as part of a “national day of rage” across the country to voice these demands and to reject Circular No. 16’s provisions of limiting a budget increase and implementing a hiring freeze in the public sector, as well as to call for the approval of a specific subvention related to pandemics and epidemics (L’Economiste Maghrébin, 28 May 2020; La Presse, 6 June 2020).

Conclusion

The impact of the coronavirus and the nationwide lockdown has once again brought socioeconomic inequalities in Tunisia to the surface. Demonstrators are increasingly calling for the government to adopt clear measures, such as providing employment opportunities and government financial assistance as well as public subsidies, to address the pandemic’s disproportionate impact on low-income communities and their access to basic services and goods. Since the revolution in 2011, Tunisia has taken significant steps to expand political freedom and to protect human rights, but it still faces major challenges to achieving equal levels of socioeconomic justice. The coronavirus and its impact on the Tunisian economy has only compounded the problems facing the country. It remains to be seen if Tunisia will remain a “democratic exception” in the region in the years to come.