As the global death toll from COVID-19 surpasses 600,000 (Johns Hopkins University, 23 July 2020), few states continue to downplay the severity of the crisis. Of the remaining holdouts, two are in Latin America: Brazil and Nicaragua. Since the beginning of the pandemic, the presidents of both countries have been condoning or explicitly supporting political gatherings, with Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro even appearing at weekly protests without a face mask.

Demonstration trends in Brazil and Nicaragua have begun to change against this backdrop. ACLED data show that while protest rates have been increasing in Brazil during the pandemic, they have been simultaneously declining in Nicaragua. These divergent dynamics, however, are both rooted in similar public perceptions of government mismanagement of the health crisis. A closer look at the data suggests that people have resorted to different means of social protest in both countries, influenced by the extent of available domestic civil society space, the coronavirus threat, and access to national and international instruments through which to express dissent.

Brazil

Political crises amidst a pandemic

The first case of COVID-19 in Brazil was reported on 26 February 2020, marking the pandemic’s arrival in Latin America’s largest country (G1, 26 February 2020). From the onset of the crisis, President Bolsonaro has opposed broad quarantine measures, minimizing the potential health effects in comparison to the predicted economic costs of a lockdown (Reuters, 30 March 2020). Local and international media outlets have reported that President Bolsonaro used the term “hysteria” (Valor Economico, 24 March 2020) when referring to the pandemic, declared that the “destructive power of the virus was being overrated” (G1, 9 March 2020), and attended several public events without wearing personal protective equipment (Folha de São Paulo, 7 July 2020).

As the number of COVID-19 cases increases, a political crisis is unfolding both within the federal government of Brazil and in its relationship with states and cities. Governors and mayors have unilaterally imposed state and city quarantine measures in the absence of support from the central government (Estadao, 25 March 2020). These restrictions have been criticized by President Bolsonaro, who has accused these leaders of purposefully exacerbating rising unemployment (Folha de S. Paulo, 21 March 2020). Additionally, following disagreements with the president over the coronavirus response, two ministers of health have either resigned or have been dismissed (G1, 16 April 2020; BBC, 15 May 2020). For more information on national versus local tensions in Brazil, see this spotlight from ACLED’s COVID-19 Disorder Tracker.

Bolsonaro is also facing a political crisis on another front. In April, Minister of Justice Sergio Moro stepped down after accusing the president of attempting to intervene in the work of the Federal Police (G1, 24 April 2020). The recent arrest of a former political advisor to the Bolsonaro family over corruption allegations, as well as ongoing investigations into a fake news network set up by the president’s supporters, are only inflaming political tensions amidst the pandemic.

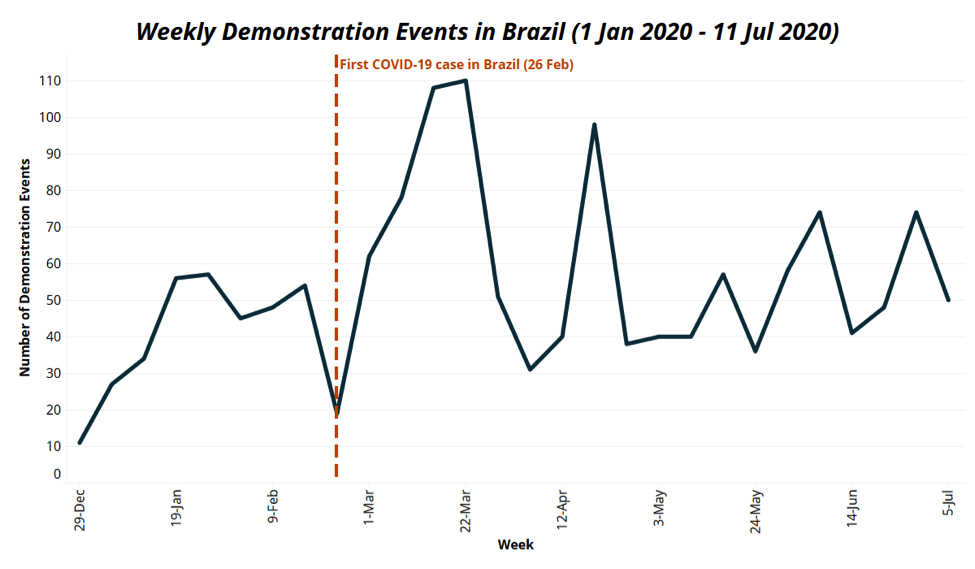

Dissent and pot-banging protests

With contradictory responses at the national and subnational level, protests are erupting across Brazil. Between March and June 2020, ACLED records over 1,000 demonstration events, the majority of which are directly related to the coronavirus response. From 174 events in February, ACLED records 406 demonstrations events in March alone — a 133% increase — mainly stemming from growing political polarization and public unrest over the severity of the crisis (see graph below). As deaths due to COVID-19 became daily announcements in the media, the uneven strategy adopted by the government has generated concerns that it is incapable of properly handling the situation. With a significant portion of the population under quarantines implemented by state governors, many Brazilians have been resorting to banging pots to protest from inside their homes. In some cities, such as in São Paulo, pot-banging protests occurred for over 15 days in a row (G1, 2 April 2020).

Initially, these pot-banging protests were aimed directly at the President Bolsonaro’s poor handling of the coronavirus pandemic. However, as the new political crisis noted above has unfolded, these pot-banging protests have become the main form of expressing general opposition to Bolsonaro and calling for his impeachment.

This form of protest has become increasingly popular in the last decade in Brazil during periods of high dissatisfaction with the government, and its use is reminiscent of the mass movements that led to the impeachment of former President Dilma Rousseff in 2016. Currently, while a small number of pot-banging protests have expressed support for the president, they remain chiefly associated with the opposition.

From the official pandemic declaration in March through the end of June, more than 200 pot-banging protest events have been documented in Brazil, with March alone accounting for more than half of these. The high number of pot-banging protest events is not only a result of movement restrictions setting constraints on public gatherings, but is also a function of Bolsonaro’s declining popularity and growing support for his impeachment (El Pais, 27 April 2020).

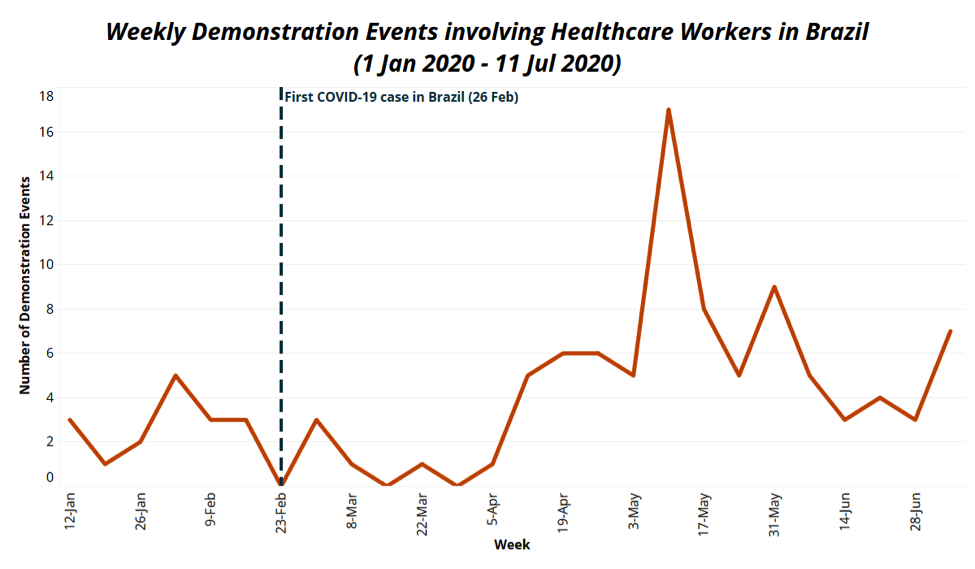

Additionally, as COVID-19 began to overwhelm the country’s healthcare infrastructure, protest events involving health workers increased drastically from March to June 2020 (see graph below). In March, just five demonstration events involving health workers were reported, compared to 36 in May and 21 in June. Health workers have been primarily calling for better working conditions amid the pandemic.

Motorcades and support for the president

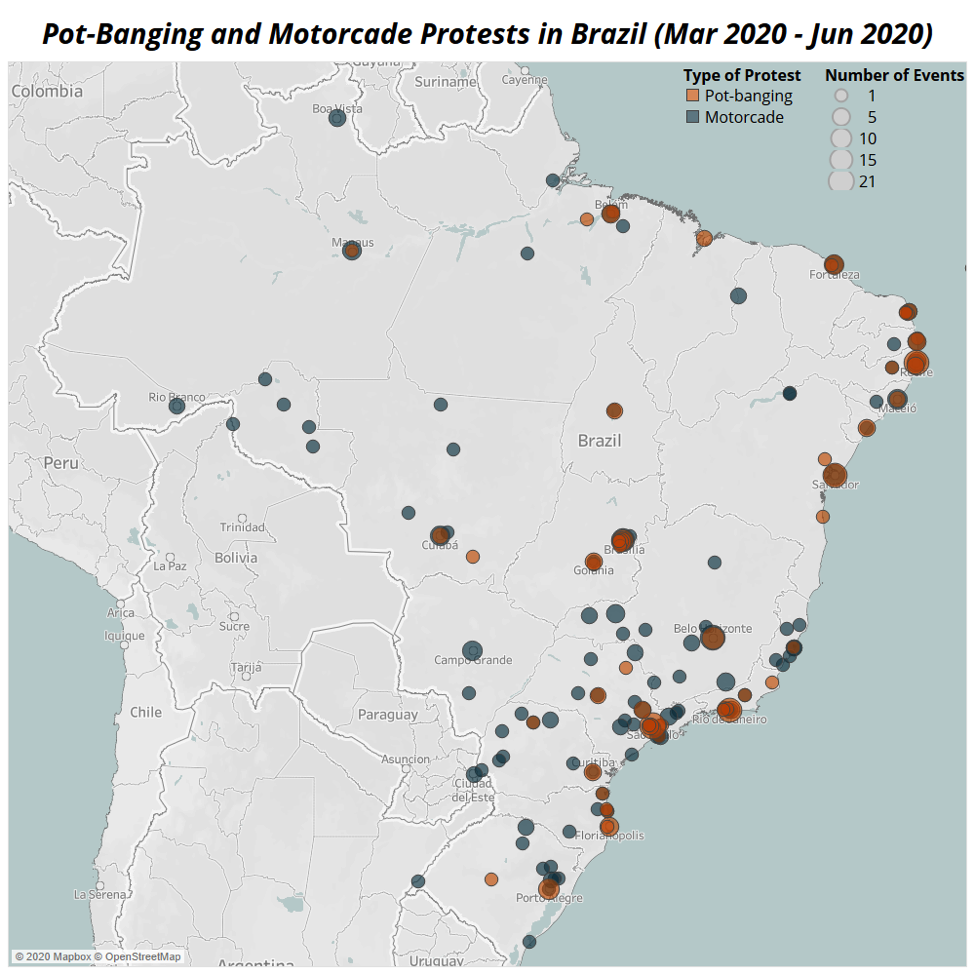

While pot-banging protests have become a symbol of approval for coronavirus-related restrictions, supporters of President Bolsonaro have been organizing motorcades to call for an end to quarantine measures. Between March and June 2020, motorcades became another common way of protesting: 172 events of this type were reported around the country. Although general support for Bolsonaro has been a common theme of the motorcade protests, the majority — 76% — have specifically demanded the end of quarantine measures implemented by state governors.

Although mostly peaceful, some motorcades have ended with police intervention. Arrests were made mainly over the violation of noise nuisance regulations, as participants in motorcades honked horns around hospitals treating COVID-19 patients, and contravened state rules prohibiting public gatherings. President Bolsonaro himself attended some of these protests, prompting criticism from local rights groups and public authorities (G1, 31 May 2020; G1, 17 May 2020).

Geographic trends

Although pot-banging protests are more common than motorcades between March and June 2020, motorcades are more widely distributed across the country, with events reported in all but one of Brazil’s 26 states as well as in the Federal District and the countryside. Pot-banging protests, on the other hand, are recorded in 21 states, and are mostly concentrated in and around larger urban centers (see map below).

The uneven distribution of the two forms of protest can be explained by the relative support for Bolsonaro in smaller cities and towns compared to the main urban centers. At the end of June, the disapproval rate for Bolsonaro in state capital cities reached 53%, in comparison to 47% in smaller cities and towns (Datafolha, 26 June 2020).

It is clear that Brazil’s protest dynamics during the pandemic have been following the developments of the political crisis. The line between public opinion on the government’s pandemic response and public opinion on the Bolsonaro administration more generally has grown even thinner. Opponents of the president have criticized his approach to COVID-19, while his supporters have mostly defended his refusal to impose a nationwide quarantine, as demonstrated by demonstration trends since the start of the outbreak. With the number of infections drastically increasing in the South and Central-West regions of the country by mid-July, state governments have had to step back in their gradual reopening plans, infuriating business owners who continue to call for the resumption of economic activities (G1, 16 July 2020). Tensions are likely to continue, especially with President Jair Bolsonaro himself testing positive for COVID-19 on 7 July, while continuing to ignore social distancing measures (G1, 7 July 2020).

Nicaragua

Demonstrations and COVID-19

Though the government confirmed the first COVID-19 death in Nicaragua in late March, concerns over the public health response were expressed soon after the WHO’s official pandemic declaration. Amidst rumors that he was suffering from poor health himself, President Daniel Ortega disappeared from public eye for about a month starting in mid-March without implementing any coronavirus-related restrictions (Reuters, 9 April 2020), allowing sports and public parties to continue unabated. When he finally appeared in a televised announcement, Ortega explained why the government did not impose a quarantine, stating that “here, if we stop working, the country dies” (El Confidencial, 16 April 2020).

By May, health workers and political activists expressed serious criticisms of the government’s pandemic response, which were echoed in international media (El Pais, 28 April 2020). The national press began documenting evidence that the coronavirus was spreading across the country, with reports of increasing patient intake at hospitals, rising respiratory diagnoses, mass grave excavations, the delivery of corpses in closed caskets to family members, and quick burials (La Prensa, 30 May 2020; La Prensa, 29 May 2020; La Prensa, 25 May 2020; Confidencial, 29 May 2020). By 17 May, the Ministry of Health confirmed a total of 17 COVID-19 deaths (Xinhua, 20 May 2020).

Nevertheless, only two demonstration events directly related to COVID-19 were reported in the country until June: one of them, the state-sponsored “Love in Times of COVID-19” march in Managua on 14 March, intended to demonstrate solidarity with countries affected by the pandemic. The march also served as a message — to the country and to the world — that the Nicaraguan government would not enforce social distancing rules, much less a lockdown. Indeed, gatherings were not restricted and, in mid-April, the government led a march to inaugurate a bridge in Granada, resulting in a gathering of dozens of people (La Prensa, 1 April 2020).

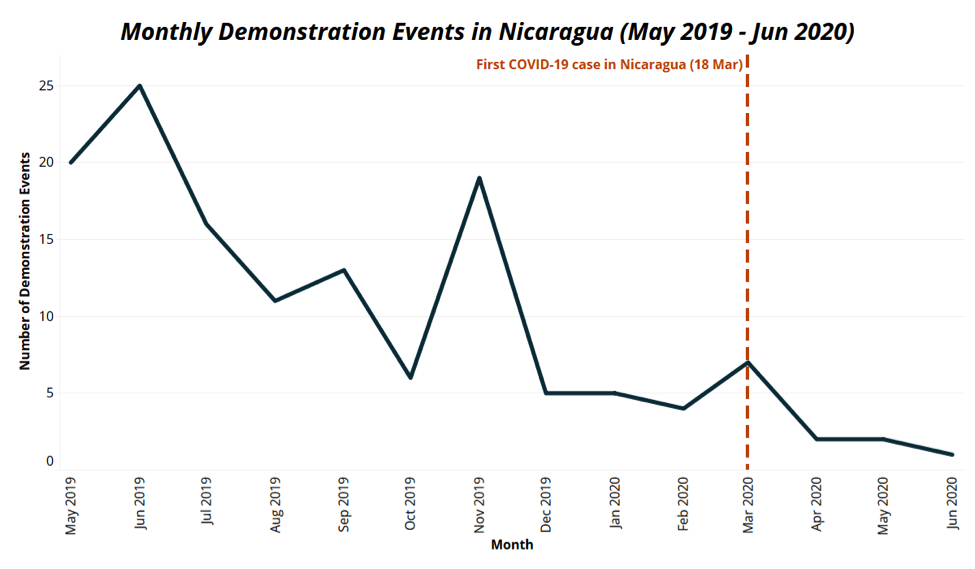

While many Nicaraguans expressed concerns over the government’s tepid public health response in the media, demonstration trends remained virtually unaltered following a decline starting before the onset of the pandemic, linked to the government’s violent crackdown on dissent, rendering public demonstrations particularly dangerous in Nicaragua rather than a result of the health pandemic. Nevertheless, ACLED data show that from March to June 2020, 12 protest events took place (see figure below), mostly around the capital, Managua. So far this year, an average of four demonstration events per month have been recorded, which, compared to 2019 (an average of 13 monthly demonstration events), represents a 69% decrease in average monthly demonstration events — though this trend is likely not driven entirely by the health pandemic given the declining trend began prior to the onset of the current health crisis.

The dynamics of dissent

Democratic space has shrunk in Nicaragua under the Ortega regime, which systematically uses violence as a deterrent against public demonstrations. In 2018, a legal reform of the social security system triggered massive demonstrations against President Ortega in several cities across the country. The government reacted with violence to suppress the protests, leaving 300 dead and 2,000 injured (OHCHR, 2019). Since then, authorities have cracked down on public displays of dissent across the country, confining demonstrations to private spaces. A de facto state of emergency persists, with severe restrictions on basic human rights like freedom of expression, assembly, and association (IACHR, 18 April 2020).

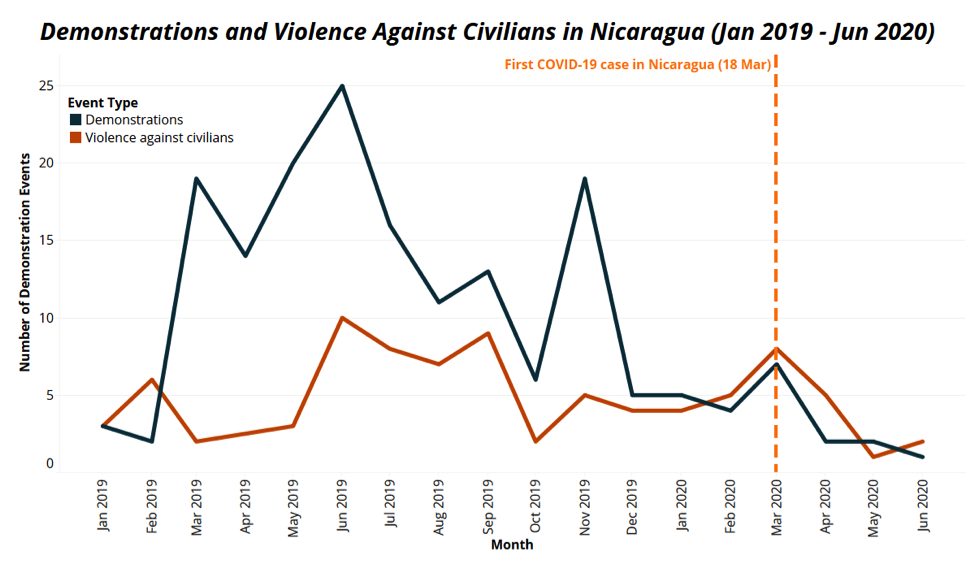

Demonstrations have increased overall in Latin America following an initial decline at the start of the pandemic (ACLED, 28 May 2020). Nicaragua did not follow this regional trend, with the number of demonstrations decreasing sharply in recent months (in navy in graph below). At the same time, violence against civilians (in brown in graph below) increased compared to months’ prior (see graph below). ACLED records multiple attacks targeting members of the opposition during this period. However lacking the government’s pandemic response has been, the repressive arm of the state has not faltered.

Since the 2018 crackdown, and amid these ongoing attacks, Nicaraguans have resorted to innovative forms of protest to express dissatisfaction with the government, while dodging state repression. The country’s student movement, the Mothers of April, and the National Unit Blue and White (UNAB) are some of the key actors driving this innovation, in close connection with certain sectors of the Catholic church. With permanent restrictions on public demonstrations, these actors have instead organized in private spaces, such as in churches and universities, and have made political use of their bodies through hunger strikes. They have also adapted and subverted national symbols, inverting the Nicaraguan flag during religious marches, for example. To document deaths from coronavirus as well as threats against the opposition, a consortium of civil society actors recently created the COVID-19’s Citizen Observatory, through which health workers and activists register coronavirus cases across the country. They have documented over 7,800 suspected cases and over 2,200 deaths as of July (Observatorio Ciudadano COVID-19 Nicaragua, 8 July 2020)

Additionally, due to the dual threats of domestic repression and coronavirus infection, civil society actors have increasingly turned to international advocacy. In 2018, international advocacy campaigns led to US, UK, and Canadian sanctions of top officials involved in the protest crackdown (HRW, 10 May 2020). Moreover, the Inter-American Commision on Human Rights (IACHR) has so far issued two press releases denouncing the Nicaraguan government’s handling of the pandemic (IACHR, 18 April 2020; IACHR, 27 May 2020). The most recent press release expressed serious concerns over violations of the right to information in the country.

Comparing the COVID-19 response in Brazil and Nicaragua

Despite similar concerns over government mismanagement of the COVID-19 response in both Brazil and Nicaragua, public unrest has taken very different forms. These divergent trends are most likely connected to the disparities in democratic and civic space available in each country.

On one hand, following an initial decrease in demonstrations, overall demonstration activity has increased across Latin America since the start of the pandemic, largely driven by healthcare workers and a desire of populations to return to ‘economic normalcy’ (see this recent COVID-19 Disorder Tracker report). While Brazil mirrors this aggregate trend with a rise in pot-banging protests, Nicaragua does not.

Nonetheless, in both countries, dissatisfaction with the government’s management of the crisis has been a key driver of demonstrations. Specific forms of protest stand out in Brazil, with pot-banging and motorcades becoming public statements of opposition or support for President Bolsonaro, respectively. In Nicaragua, state repression has forced would-be protesters to find alternative outlets for dissent, with critics voicing their concerns through news reports, citizen’s initiatives, and international advocacy using the regional human rights system.

Public perception of the pandemic’s medical and economic impacts in Brazil will continue to influence the level of support for President Bolsonaro. With the country emerging as one of the global hotspots of COVID-19 with over 80,000 reported deaths as of 20 July (G1, 21 July 2020), the federal government faces mounting pressure to present effective solutions under scrutiny from both national and international actors. It is likely that demonstrations will continue to take place around the country, fueled by political polarization and growing awareness of how the federal government’s response is negatively impacting public health.

In Nicaragua, whistleblowers reporting the situation to international media and human rights institutions are at risk of reprisal. Those in the public health sector could be fired, aggravating an already understaffed healthcare system struggling to address the pandemic. Ultimately, the root causes of protest in the age of coronavirus, such as authoritarianism and the lack of transparency and information, existed prior to the crisis and are likely to remain in place for the foreseeable future.

The similar pandemic response of both presidents triggered different, context-specific reactions. Still, both have faced widespread criticism for failing to properly address the crisis. With presidential elections set for 2021 in Nicaragua, the public perception of the government’s management of the health crisis will heighten political tension and will likely impact results. In Brazil, President Bolsonaro may try to dissociate himself and his government from the pandemic response as both the public health crisis and the associated political crisis erode his support across the country. How Bolsonaro and Ortega manage such dual crises will ultimately define their reelection prospects — and thus the continuity of the political projects they represent.