In our special report on 10 conflicts to worry about at the start of 2020, ACLED identified a range of flashpoints and emerging crises where violent political disorder was likely to evolve and worsen over the course of the year: the Sahel, Mexico, Yemen, India, Somalia, Iran, Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Lebanon, and the United States. Our mid-year update revisits these 10 cases more than six months on — in a world disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic — and tracks key political violence and protest trends to watch in the second half of 2020.

![[cover] dashboard (1)](https://acleddata.com/acleddatanew/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/cover-dashboard-1-2-1024x761.png)

Mid-Year Update: 10 Conflicts to Worry About in 2020

Please click through the drop-down menu below to jump to specific cases.

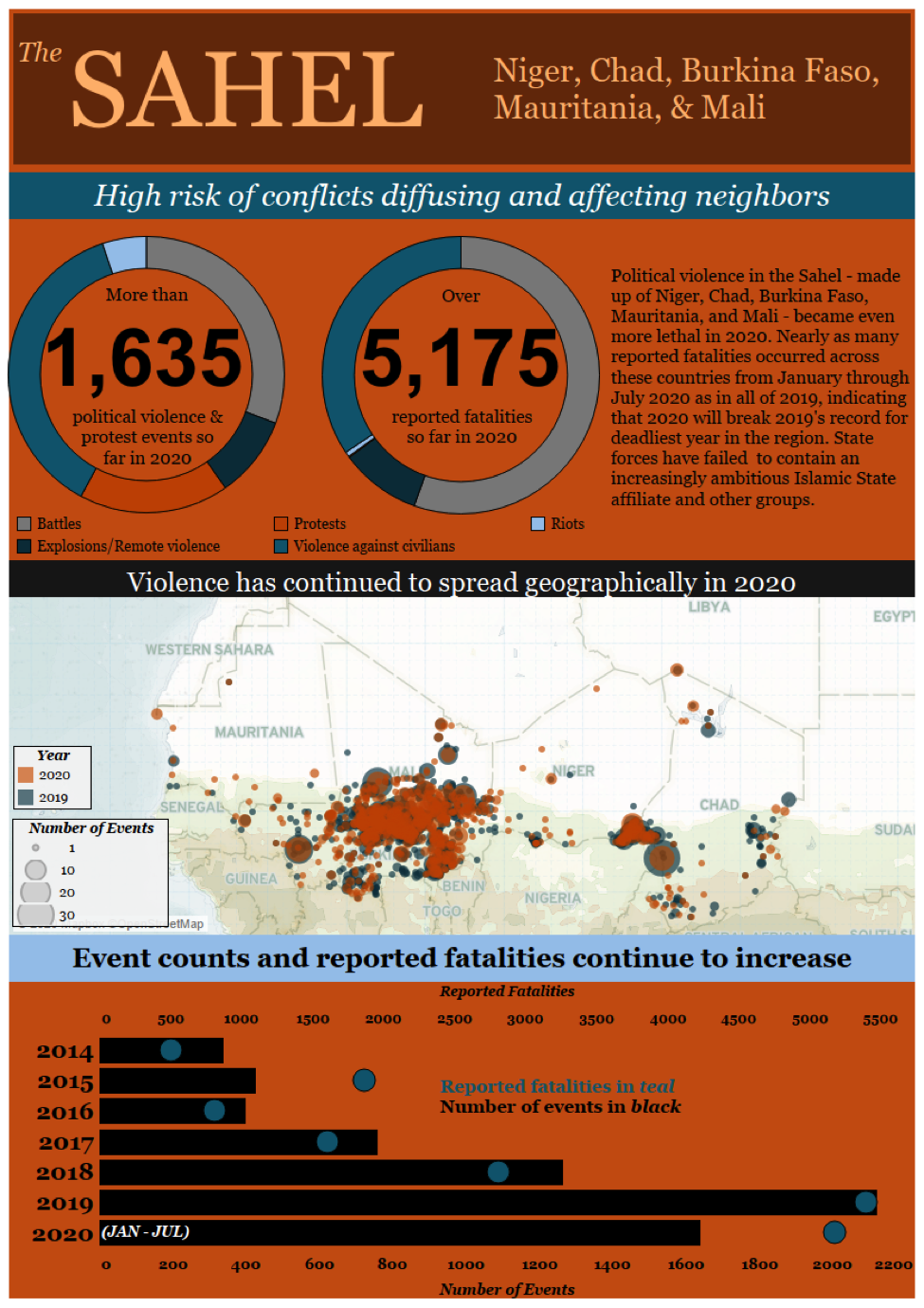

In the Sahel, persistent conflicts have raged on for more than eight years and show no signs of abating. Instead, the multidimensional crisis is escalating and expanding across the region. Halfway through 2020, the number of reported fatalities in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger has either neared or surpassed the full total for each country in 2019. The rising death toll is driven by multi-directional violence perpetrated by primarily jihadi militant groups, state forces, and ethnic/community-based militias (Sahelblog, 24 July 2020). In the first months of 2020, the region experienced a sharp rise in violence targeting civilians by government forces, as local and foreign forces stepped up their operations to counter the jihadi onslaught by the Al Qaeda-affiliated Jama’ah Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) and the Islamic State in Greater Sahara (ISGS), or the Greater Sahara faction of Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) (for more, see ACLED’s report on state atrocities in the Sahel).

At the beginning of 2020, ACLED assessed a high risk of conflicts in the Sahel diffusing and spilling over into neighboring countries amid a continuous southward encroachment of mobile threats to the security of West African coastal states (ACLED, 23 January 2020). This came to pass in June, when Ivory Coast suffered a deadly attack on a border post in the country’s extreme north. Militants believed to be JNIM staged an assault on a mixed army and gendarmerie position in the village of Kafolo, killing 14 troops (Koaci, 2 July 2020). The attack in Kafolo represented the first jihadi militant attack in Ivory Coast since the 2016 shootings at the Grand-Bassam resort.

Fighting between militant groups is also intensifying. After ISGS was formally integrated into ISWAP, tensions and skirmishes increased with JNIM. Ideological divisions have hardened between the two groups, and ISGS has increasingly challenged the hegemony of its Al Qaeda counterpart as its ambitions have grown (CTC, 31 July 2020). The rising tensions escalated into open warfare in Mali and Burkina Faso in early 2020, and evolved into a full-fledged turf war throughout the first half of 2020. In the first six months of 2020, ACLED records 34 armed engagements between the two jihadi franchises, leaving more than 300 militants dead. Considering the upsurge in jihadi-on-jihadi fighting, militant groups are currently, to a significant degree, contesting territory more between each other than with the concerned states.

In Burkina Faso, the parliament approved a bill authorizing the training and arming of civilians to supplement conventional forces in their fight against jihadi militant groups (Le Faso, 21 January 2020). First and foremost, the creation of volunteer fighters, or Volunteers for Defense of Homeland (VDP), represented a formalization of pre-existing community-led security and largely ethnic-based militias — including Koglweogo and Dozos — within state structures, contributing to further escalation of violence. Moreover, the recent killing of the mayor of Pensa and a complex ambush against the security escort of the president of the Higher Council for Communication highlight the growing conflict in Burkina Faso, and the imminent risks posed ahead of presidential and legislative elections planned for November.

In neighboring Mali, JNIM militants and Fulani militias have conducted incessant attacks against Dogon villages to isolate and subjugate Dogon communities, as well as to hamper the harvest season. These attacks have led many Dogon villages to distance themselves from the majority-Dogon Dana Ambassagou movement. In this context, JNIM posited itself as an arbitrator to solve the conflict between Fulani and Dogon in Koro, in the central Mopti Region, thus increasingly taking on governing responsibilities.

Beyond armed conflict, Mali is currently experiencing a socio-political crisis amid a series of mass demonstrations against the regime, to which government forces have responded with brute force. The demonstrations — monikered the Movement of June 5 – Rally of Patriotic Forces (M5-RFP) — are organized by a loose coalition of religious leaders, opposition figures, and civil society, spearheaded by the influential imam Mahmoud Dicko, who has called for civil disobedience until president Ibrahim Boubacar Keita resigns. Keita is viewed by the protest camp as the embodiment of bad governance, corruption, and the state’s failure to reduce conflict (ECFR, 22 July 2020).

In Chad, militants of Jama’atu Ahlis-Sunna lid-Dawati wal-Jihad (JAS), or Boko Haram, carried out the deadliest attack ever recorded in Bohoma, killing at least 92 soldiers (Jeune Afrique, 25 March 2020). Chadian authorities responded to the attack by launching the 10-day operation “Anger of Bohoma,” and claimed to have killed 1,000 insurgents as a result of the operation (Alwihda, 9 April 2020). While the army triumphantly said it had chased away Boko Haram from the lakeside, militant activities soon resurged. President Idriss Deby admitted in an August interview that Boko Haram militants “would continue to wreak havoc in the Lake Chad region” in spite of the large-scale offensive (France24, 9 August 2020).

The creeping progression of militant groups constitutes an immediate threat to the northernmost border regions of countries such as Benin, Togo, and Ivory Coast. Increased jihadi militant activities have also been recorded in recent months in Mali’s southern regions of Sikasso, Kayes, and Koulikoro. There is an imminent risk that hostilities between JNIM and ISGS will spread to areas so far spared from violence, and potentially exacerbate conflict along ethnic or tribal fault lines. Increased competition between the groups could lead to deadlier attacks.

Meanwhile, the impact of the coronavirus pandemic has so far been relatively limited in Sahelian countries. Measures to counter the spread of the virus were difficult to impose by the authorities and triggered popular discontent due to their impact on mobility and economic and daily life. For instance, in Niger, the closure of mosques and ban on Friday prayers resulted in violent demonstrations in several localities. To reduce tensions, the Nigerien government authorized the reopening of mosques. In Burkina Faso, tensions arose from the closure of markets; the measure was lifted after five weeks. A curfew declared by the Malian government was met by demonstrations and the curfew was then lifted after six weeks. Thus, authorities often quickly submitted to popular demand in order to reduce tensions arising from the potential economic impact of pandemic related measures.

Further reading:

- State Atrocities in the Sahel: The Impetus for Counterinsurgency Results is Fueling Government Attacks on Civilians

- CDT Spotlight: Navigating Through a Violent Insurgency in Mali

- States, Not Jihadis, Exploiting Corona Crisis in West Africa

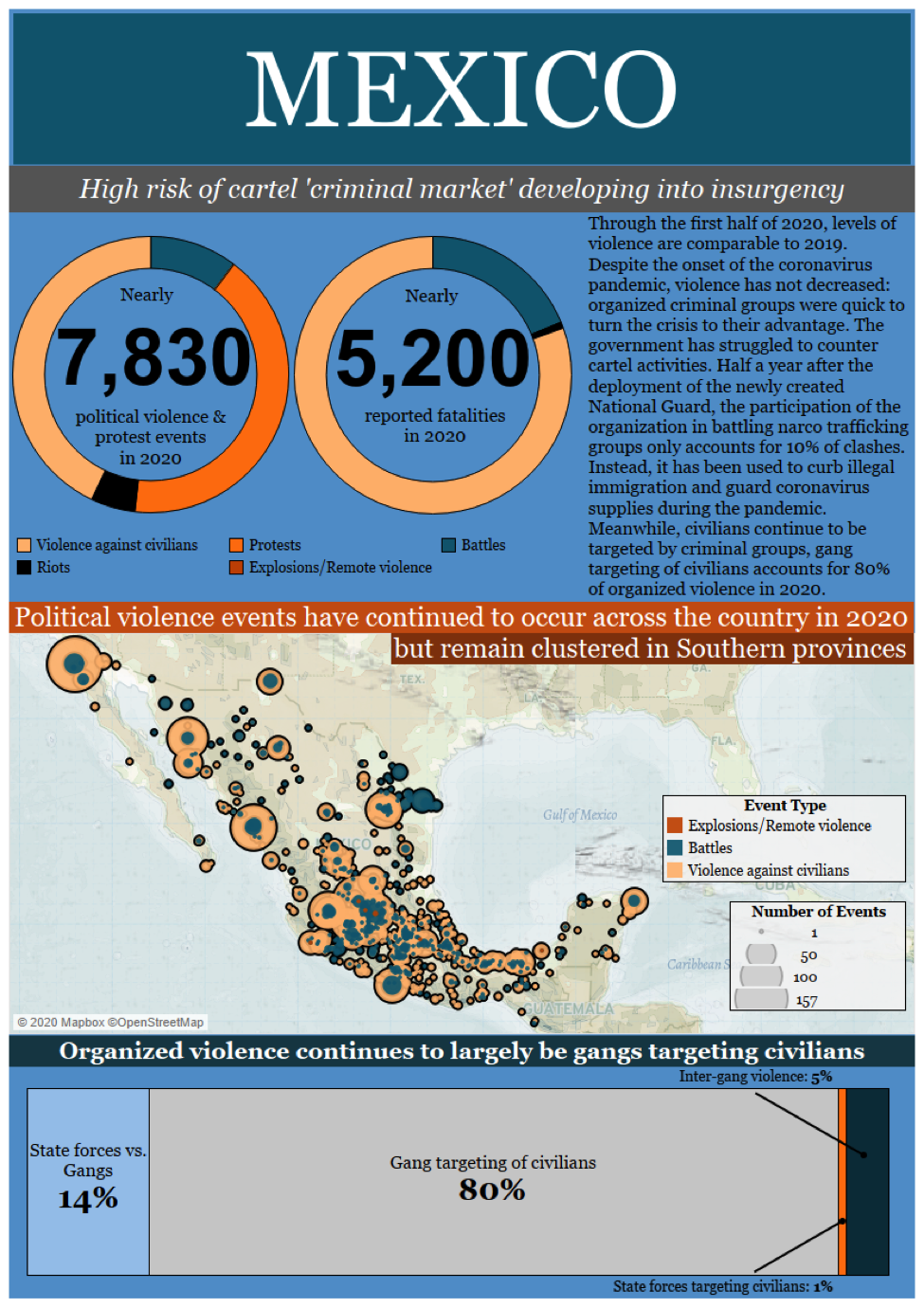

Last year ended with a record number of homicides in Mexico, and ACLED records comparable levels of violence through the first half of 2020. Despite the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, violence has not decreased. Organized criminal groups were quick to turn the crisis and virus-related confinement measures to their advantage.

In July 2020, ACLED recorded more violence against civilians involving gangs, though a slightly lower number of civilian fatalities, compared to July of last year. Though lockdown measures resulted in a net decrease of petty crime by 40% and a 20% drop in kidnappings and theft compared to 2019, drug dealing rose by 12% (Executive Secretariat of the National Public Security System, 20 July 2020). Several conclusions can be drawn from these figures and their implications for the gang landscape in Mexico. Weakened cartels and smaller splinter groups rely on diversified sources of revenue such as kidnapping, extortion, fuel theft, and human trafficking, all of which were significantly impacted by coronavirus confinement policies. So far in 2020, ACLED records a sharp drop in kidnappings perpetrated by criminal groups.

Meanwhile, larger cartels that are able to withstand the crisis have kept business as usual: drug seizures, armed clashes, and violence against civilians involving criminal groups have not been affected by coronavirus restrictions, remaining at similar overall levels compared to 2019. At the same time, some criminal groups used the weakening of their rivals as an opportunity to further expand their territory. The Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG), one of the most powerful cartels currently operating in Mexico, increased its activities in states bordering its stronghold, such as in Tamaulipas state, where they had a limited presence last year. Turf wars between cartels over the control of drug trafficking routes intensified. In Michoacan, though it is now only August, clashes between the CJNG and its rival Los Viagras exceed that of 2019 already. Similarly, clashes between the Gulf Cartel and the North-East Cartel over control of the Mexico-US border in Tamaulipas have reached unprecedented levels compared to 2019.

In the midst of violent clashes and retaliatory attacks, organized criminal groups have been waging a battle over popular support and have used the pandemic to reinforce their popularity through the distribution of branded aid. In some areas, cartels enforced curfews to prevent the spread of the coronavirus, threatening anyone daring to defy the measure (CIDE, 27 April 2020).

In the context of heightened gang violence, fear that cartels may overpower Mexican state forces persists. In July, following the release of a video displaying a procession of CJNG members a few days before his visit, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador renewed his vow to tackle organized crime by fighting poverty and preventing further cartel recruitment (OCCRP, 21 July 2020). Due to the economic fallout from the coronavirus pandemic, and with gangs positioning themselves as humanitarian benefactors, this commitment may prove difficult to fulfil. The Mexican economy has already lost over one million jobs since March (Reuters, 12 June 2020), and the president remains opposed to the bailout of private companies, auguring even greater job loss. This promises a long recovery for the labor market, providing the unemployed an additional incentive to join the narco business. In addition, organized criminal groups enjoy higher levels of liquidity; their cash flow allows them to position themselves as lenders. In turn, this could create a new extortion model, giving cartels another source of income during the pandemic (The Conversation, 15 May 2020).

The government’s security strategy has so far failed to bear fruit. By some accounts, coronavirus lockdown measures could increase the visibility of cartel activities and play in favor of the Mexican state. The capture of the leader of the Santa Rosa de Lima cartel on 2 August was a significant victory for Mexican law enforcement (DW, 2 August 2020). However, the number of drug seizures and clashes between criminal groups and law enforcement remain similar to levels recorded prior to the pandemic.

Furthermore, half a year after the deployment of the newly created National Guard, the Mexican government still struggles to contain the growth of gang activities. In 2020, the participation of the National Guard in battling narco trafficking groups only accounted for 10% of clashes. The National Guard has at times shifted from its primary security function and instead contributed to the Mexican government’s efforts to curb illegal immigration or to guard coronavirus supplies and facilities during the pandemic (Aristegui Noticias, 11 April 2020). In a similar vein, the government allowed the shifting of municipal funds usually allocated to fight gangs to the health crisis (Infobae, 25 April 2020), further weakening the ability of local authorities to deter organized crime.

Civilians continue to be both caught in the crossfire and used as a medium for macabre messages sent between criminal groups. In the state of Guanajuato, 26 people were killed in an attack launched by the Santa Rosa de Lima Cartel targeting a narco rehabilitation center sponsored by a rival group (New York Times, 2 July 2020). Journalists and political figures continue to be specifically targeted, underscoring the cartel stranglehold on Mexican institutions weakened by rampant corruption. This trend is likely to worsen as the pandemic continues in cases where attacks can be monetized, as demonstrated by the recent kidnapping of a mayor in the state of Tamaulipas by the Gulf Cartel. The Gulf Cartel is aiming to diversify its activity by engaging in targeted kidnappings to increase its liquidity amid the pandemic (El Blog del Narco, 30 July 2020). More worrying, criminal groups have begun forcefully recruiting children to participate in clashes in the Tierra Caliente, a hotspot for gang violence (El Blog del Narco, 1 August 2020).

Increased levels of violence are expected as the country resumes economic activity. As it struggles to address the pandemic, Mexico’s government is facing evolving challenges in the fight against organized crime. Smaller groups that were hit harshly by coronavirus lockdown measures will further splinter and redouble violence to recover from their economic losses. Larger groups will continue to strengthen their former and newly acquired territories, presaging intensified clashes with both state forces and rival gangs. Civilians will certainly be the main targets of new cartel strategies to rebuild revenue, while deepening poverty could create a steady stream of fresh recruits.

Further reading:

- CDT Spotlight: Demonstrations in Mexico

- Central America and COVID-19: The Pandemic’s Impact on Gang Violence

- CDT Spotlight: Mexican Cartels

- ACLED Resources: Mexican Gang Violence

- Disorder in Latin America: 10 Crises in 2019

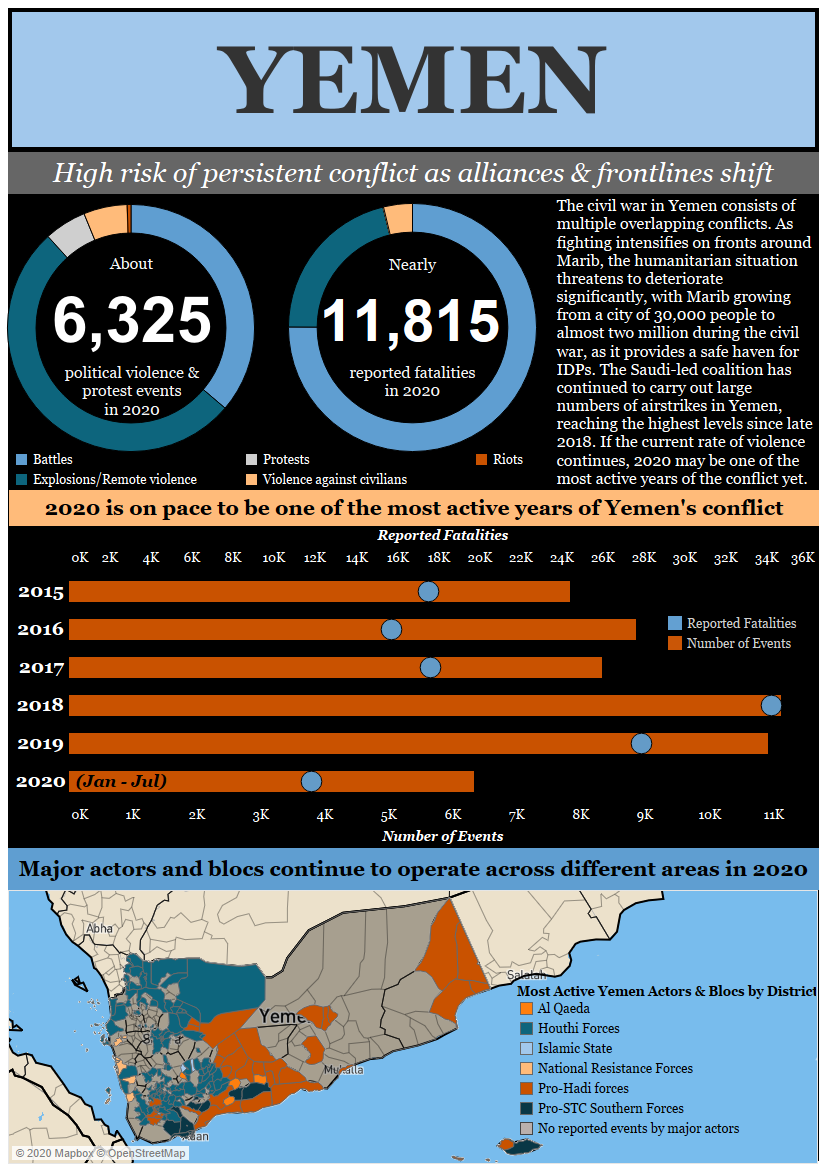

Yemen’s civil war continues unabated. Backchannel negotiations between the Houthi movement and Saudi Arabia (Middle East Institute, 15 April 2020) significantly reduced cross-border attacks and airstrikes in the first quarter of 2020. Without a successful conclusion to these talks, however, Houthi forces have intensified offensives to advance on Marib city, the anchor and stronghold of the internationally recognized government. Gaining control of Marib city would open up the possibility for Houthi forces to access the nearby oil and gas resources (Twitter, 2 July 2020). However, sanctions and the Saudi blockade will make it difficult for them to sell these resources on the international market.

Houthi forces managed to capture Al Hazm on 1 March, the provincial capital of Al Jawf governorate, and have advanced on Nihm and Sirwah fronts further towards Marib. By mid-2020, however, frontlines stagnated around Marib without any significant advancements by either side.

In the same vein, a small tribal uprising in Radman al Awad in April, led by Yaseer al-Awadhi, was crushed by Houthi forces (Middle East Institute, 22 June 2020), subsequently enabling Houthi forces to capture Qaniyah and surrounding territories, opening up another possibility to move towards Marib from the south.

Simultaneously, to alleviate pressure on forces fighting for the internationally recognized government, Saudi-led coalition airstrikes have upticked significantly, reaching their highest levels since late 2018 — before the conclusion of the Stockholm Agreement and later the initiation of Houthi-Saudi backchannel talks in September 2019. Houthi attacks on Saudi Arabia, however, have remained at their lowest levels since June 2016, with very few intrusions into Saudi territory reported. The main modes of operation include drone strikes and ballistic missile attacks, which the Saudi military claims to intercept in most cases. Still, compared to the first half of 2019, half as many of these attacks have been reported.

In the southern provinces, there has been an increasing number of contentious hotspots. In the first half of 2020, confrontations between pro-Southern Transitional Council (STC) forces and forces belonging to the internationally recognized government continued to take place, despite the conclusion of the Riyadh Agreement in October 2019. The Riyadh Agreement has not yet been successfully implemented, despite several amendments in recent months. The latest of these amendments at the end of July has been lauded by the STC and the internationally recognized government. As a result, the STC retracted its declaration of self-administration over Yemen’s south from April 2020. The plan has seen the appointment of a new security director and a new governor for Aden, though both are STC-affiliated (Twitter, 29 July 2020). The STC, however, retains de facto control of Aden, Lahij, parts of Abyan, and Ad Dali, and took control of the strategic Socotra island in June 2020 (Reuters, 21 June 2020). How the renegotiated deal from July 2020 will be implemented in the second half of 2020 remains yet to be seen. In all southern governorates, the success of implementation will be crucial in determining future patterns of violence.

The ultimate outcome of the Houthi advance on Marib on one hand, and the de facto success of the Riyadh Agreement on the other, will be critical for the future of the war in Yemen in 2020.

The civil war consists of multiple overlapping conflicts, with multiple domestic and foreign actors with competing interests and divergent capabilities. As fighting intensifies on fronts around Marib, the humanitarian situation threatens to deteriorate significantly, with Marib growing from a city of 30,000 people to almost two million during the civil war, as it provides a safe haven for IDPs (International Crisis Group, 17 April 2020). On the other hand, Saudi efforts to push for the implementation of the Riyadh Agreement raise some hope that conflict in the southern governorates will decrease in the second half of 2020.

Finally, if Saudi-Houthi backchannel talks are reactivated and result in a partial Saudi disengagement, it will have a major effect on the trajectory of the war. Nevertheless, as long as the different Yemeni sides do not come to an agreement between themselves, violence will continue — as evidenced by the Houthis starting an offensive on Marib in the first half of 2020, precisely when Saudi Arabia has shown willingness to disengage.

The coronavirus pandemic — despite infections in Yemen being widespread since April, reportedly leading to severe medical shortages (Sky News, 18 May 2020; AP, 9 June 2020) — has not significantly impacted the trajectory of the war in Yemen.

Further reading:

- Little-Known Military Brigades and Armed Groups in Yemen: A Series

- CDT Spotlight: Conflict Escalation in Yemen

- ACLED Methodology: Yemen Conflict

- Yemen’s Fractured South

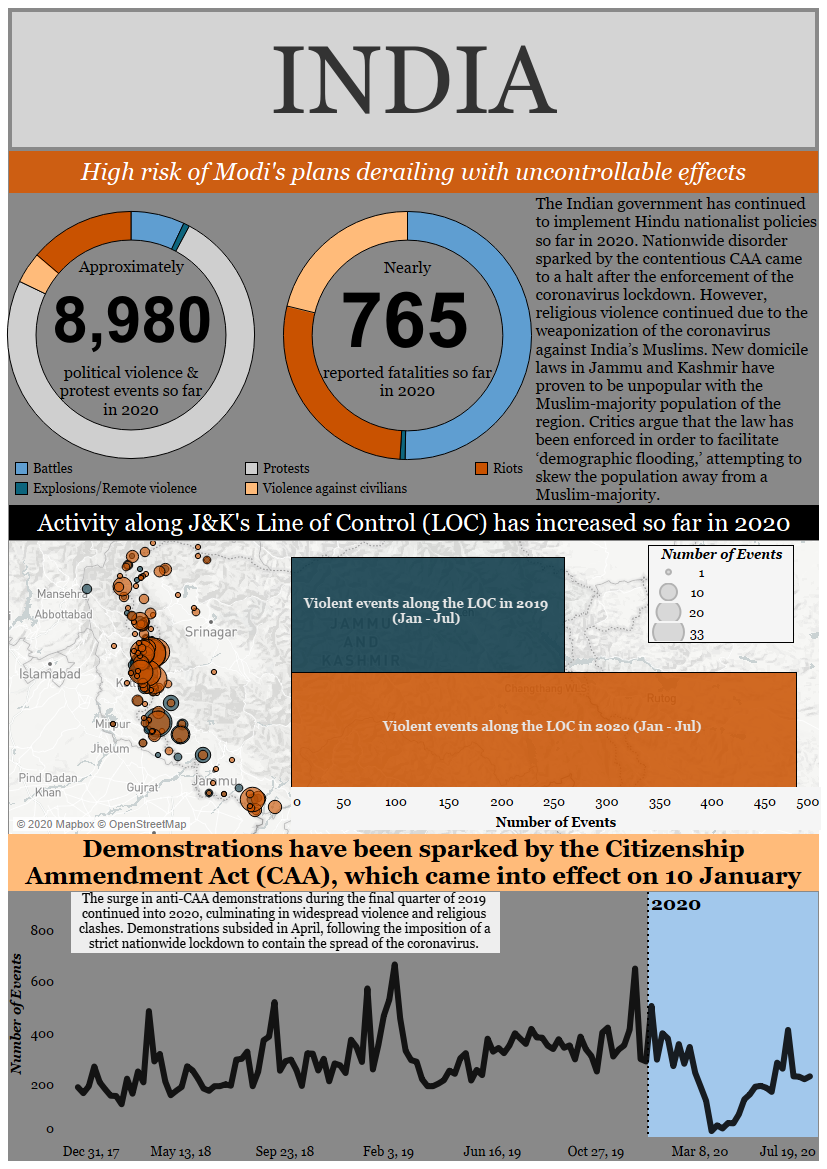

Discontent surrounding the passage of the controversial 2019 Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA) intensified across India in 2020. The CAA, which came into effect on 10 January 2020 (Gazette of India, 10 January 2020), grants citizenship rights to undocumented non-Muslim immigrants from three neighboring Muslim majority countries – Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. The law denies Muslim migrants the same citizenship rights, which has led to criticism that it discriminates against Muslims (Al-Jazeera, 16 December 2019). In India’s culturally diverse northeastern states, opposition to the CAA revolves around concerns over the Act’s implications for demographic changes in the region. Tribal groups in the northeast fear the CAA will localize a large population of non-tribal residents, particularly Hindus from neighboring Bangladesh. In addition to skewing the demographics of the region, tribal groups have concerns about burdening resources, as well as threats to indigenous languages and cultures (Economic Times, 17 December 2019). Women’s groups also oppose the law as Indian women are less likely to have access to the documentation required to prove their citizenship (Foreign Policy, 4 February 2020). ACLED has recorded the participation of women’s groups in over 10% of CAA-related demonstrations in 2020.

The surge in anti-CAA demonstrations during the final quarter of 2019 continued into 2020, culminating into widespread violence and religious clashes. During the first seven months of 2020, ACLED has recorded over 1,500 disorder events related to the CAA, including nearly 60 reported fatalities. Violence has been reported between supporters and opponents of the Act, and between demonstrators and police. Some communist leaders accused the police of acting as an extension of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) (Outlook, 14 February 2020). Attacks on anti-CAA demonstrators were also perpetrated by right-wing, Hindu nationalist groups including BJP, Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP), and Bajrang Dal, as well as individual perpetrators shooting at demonstrators. Amid the surge in unrest, some BJP leaders were accused of inciting violence against anti-CAA demonstrators while campaigning for Delhi’s Legislative Assembly election (National Herald, 9 February, 2020; BBC, 29 January 2020). The pro-CAA and anti-Muslim rhetoric used by BJP leaders for electoral campaigning has entrenched the Hindu-Muslim divide, leading to deadly religious riots between Hindu and Muslim communities in Delhi. The riots reportedly led to over 50 fatalities, with Muslims accounting for two-thirds of those (New York Times, 3 March 2020).

The neutrality of Delhi’s police force, which reports directly to the BJP-led union government, was also questioned during the riots (BBC, 25 February 2020). Police personnel reportedly stood by while Hindu mobs attacked Muslim civilians and destroyed their property and places of worship (New York Times, 27 February 2020). CAA-related violence and demonstrations subsided in April, following the imposition of a strict nationwide lockdown to contain the spread of the coronavirus. Since the enforcement of the lockdown, a small number of CAA-related demonstrations have been reported. ACLED records an increase in these demonstrations in northeast India during the month of July, suggesting that widespread anti-CAA demonstrations could resurface with the potential for more violence.

Despite the onset of the pandemic, religious violence has continued due to the weaponization of the coronavirus against India’s Muslims. A spike in violence against Muslims was recorded after Indian authorities linked several coronavirus cases to a conference organized in Delhi by Tablighi Jamaat, an Islamic missionary group. Fake news campaigns on social media against Muslims spawned more attacks (Wire, 16 May 2020; Time, 3 April 2020), while BJP leaders were accused of perpetuating the anti-Muslim narrative (Al Jazeera, 29 April 2020). In West Bengal state, police filed cases against two BJP MPs accused of inciting violence during coronavirus-related clashes between Hindus and Muslims, which lasted several days (Indian Express, 18 May 2020).

With the coronavirus pandemic in the backdrop, the Indian government took measures to introduce a new law for the union territory of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K). The region’s limited autonomy was initially revoked in August 2019 following the controversial abrogation of articles 370 and 35 A of the Indian constitution. The new law, announced almost eight months after the revocation of the former state’s autonomy, allows a path for Indian citizens from other areas to settle permanently in the region, including the children of central government officials. Similar to the CAA in the northeast, the new law in J&K is considered a threat to the demographics of a region that was previously India’s only Muslim-majority state (Al-Jazeera, 3 April 2020). Opponents of the law also criticized the timing of its introduction, claiming that it was announced during a nationwide lockdown to avoid public outrage (Hindustan Times, 4 April 2020). Increasing discontent and religious divides, fueled by recent events, may contribute towards greater support for militancy in the region.

An increase in events and fatalities involving Indian security forces and militant groups was reported in J&K following the imposition of the nationwide coronavirus lockdown. Reports suggest that Indian forces have used the lockdown to commit resources towards stamping out militancy in the region (New India Express, 7 May 2020). ACLED records 30 violent events and nearly 50 fatalities involving security forces and militants during the first quarter of 2020. Following the imposition of the lockdown, over 80 events and 140 fatalities were recorded during the second quarter of the year. Despite significant gains against militancy in the region, militant groups like the newly formed Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) off-shoot, Resistance Front (RF), continue to seek greater influence in the region (Outlook, 26 April 2020). Islamic State (IS) affiliates have increased their activity in the region during the lockdown and have been involved in several clashes with security forces. IS is reportedly focused on recruiting Indian Muslims in the aftermath of the CAA riots (Diplomat, 30 March 2020). Recently, LeT militants targeted and issued threats against BJP leaders in the region in retaliation for alleged Indian Army activity against civilians and families of militants in J&K (Asian News Hub, 15 July 2020). Some BJP activists have resigned following the attacks (Hindu, 15 July 2020). With militant groups vying for greater influence, and Indian security forces focusing on tackling militancy, a surge in violence between militants and security forces can be expected in J&K going forward.

Internationally, escalated cross-border violence with Pakistan and recent clashes with Chinese forces have raised the risk of serious international confrontation. Indian forces in Kashmir may have to contend with the threat of a Pakistan-China alliance, as well as domestic militancy and growing dissent amongst the local population. This year, a significant increase in cross-border violence between Indian and Pakistani forces was reported across the Line of Control (LoC) in the Kashmir region. ACLED records 480 clashes and 130 fatalities between Indian and Pakistani forces during the first seven months of the year, compared to 260 clashes and 69 fatalities over the same period in 2019. The sharp increase in cross-border violence puts 2020 on pace to become the most violent year recorded between India and Pakistan since the beginning of ACLED coverage in 2016. Meanwhile, recent tension between Indian and Chinese forces is centered around infrastructure development projects initiated by India along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) (Washington Post, 2 June 2020). In response, China deployed troops and initiated its own infrastructure projects in the region, including the construction of military installations in Indian territory (BBC, 16 June 2020; BBC, 25 June 2020). Clashes were reported along the LAC in May and June, with the most recent one resulting in the death of 20 Indian soldiers and at least one Chinese soldier. As of July, both sides have taken measures to de-escalate hostilities along the LAC (New York Times, 6 July 2020). Despite this, India now faces the possibility of active cross-border conflict with both Pakistan and China: regional allies with a long history of economic and military cooperation (South Asian Voices, 25 May 2020).

Further reading:

- CDT Spotlight: Political Violence in the Path of Cyclone Amphan

- CDT Spotlight: Continuing Conflicts in India

- CDT Spotlight: India

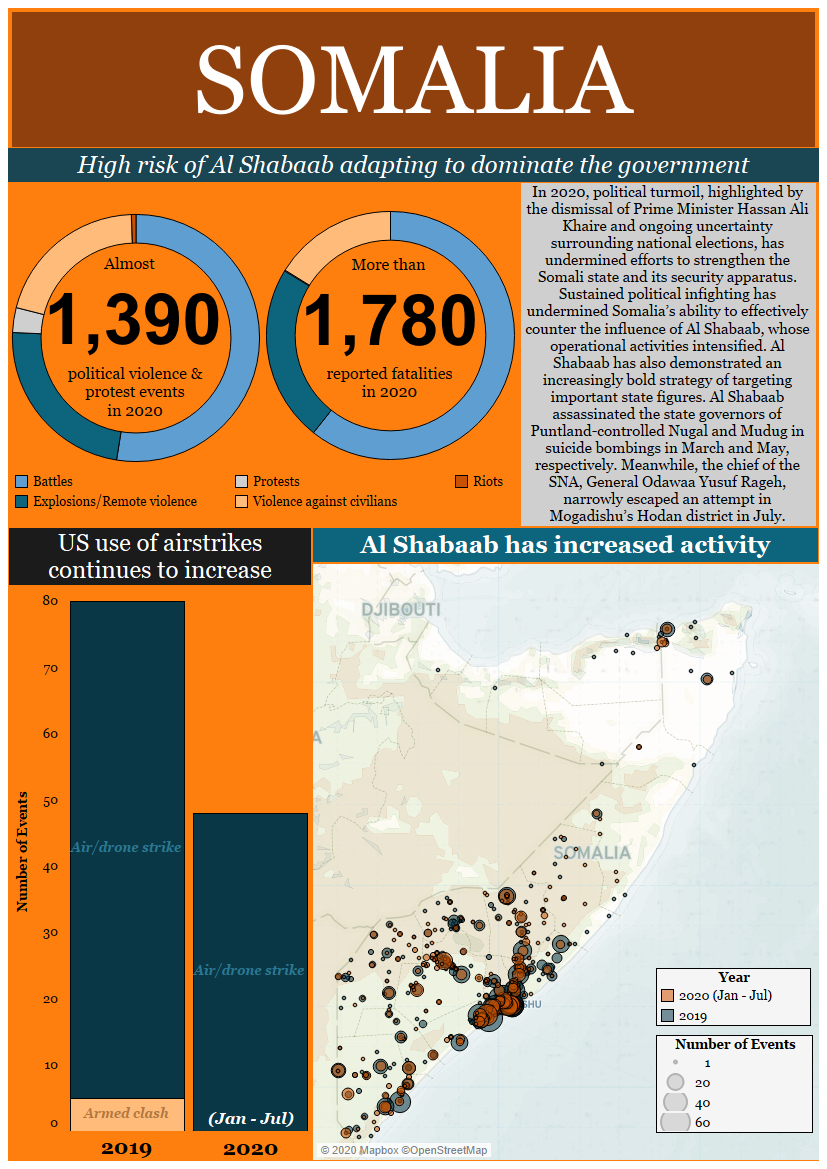

2020 was set to be the year in which universal suffrage was realized in Somalia for the first time since the outbreak of civil war in 1992. This outcome is now looking increasingly remote. Despite recent agreement on new elections, there remains a lack of consensus over the exact form they should take, amid ongoing distrust between and within Somalia’s federal government and the federal member-state governments. Aside from undermining institutional progress in the country, such discord has also had a very real effect on the fight against Al Shabaab. Earlier this year, ACLED warned that a weak government in Somalia faced a high risk of being dominated and isolated by Al Shabaab. Analysis of the latest data indicates that this prediction has been borne out.

In July, the Dhuusamarreeb forum engaged the federal government and the federal member states in direct discussions over matters of security and the evolution of political processes in the country. The forum was seen as a positive step and ended in agreement over the holding of national elections before the end of the year (Garowe Online, 23 July 2020). This is where the agreement ends, however. President Mohamed Abdullahi Farmajo has continued to push for one person, one vote elections (Somalia Affairs, 22 July 2020), despite the electoral commission having earlier declared that credible popular elections would be impossible to hold this year (CGTN, 28 June 2020). In contrast, federal member states released a joint statement calling for the development of an alternative model to one person, one vote, in order to guarantee that the upcoming election will take place within the scheduled time (Garowe Online, 13 July 2020).

Furthermore, the post-Dhuusamarreeb removal of Prime Minister Hassan Ali Khaire from office in a vote of no confidence by parliament has worsened discord between governments. Puntland President Said Abdullahi Dani declared the removal ‘illegal,’ accusing President Farmajo of dishonesty and orchestrating the vote of no confidence in order to push for an election delay (Garowe Online, 27 July 2020). This is a sentiment that has been echoed by the federal parliamentary opposition (Garowe Online, 26 July 2020). Key international partners, including the European Union and the United Nations Assistance Mission in Somalia (UNSOM), have also expressed their concerns (DW, 28 July 2020).

The current distrust between the various governments of Somalia is symptomatic of a much wider dissonance. These are profound disagreements which connect to territorial control, political legitimacy, and the very structures defining the Federal Republic of Somalia. They have spilled out into direct violent confrontation between rival state forces. Since the beginning of the year, clashes have been reported between Somaliland and Puntland forces over territorial disputes in the Sool and Sanaag regions, as well as between Galmudug and Puntland forces in Mudug. Jubaland forces and the Somali National Army (SNA) also clashed in Gedo over the Jubaland government’s alleged protection of a fugitive former minister wanted by the central government. Meanwhile, the Sufi militia Ahlu Sunna Wal Jamaa (ASWJ), former allies with the state in the fight against Al Shabaab, clashed with state forces in Dhuusamarreeb city over rival claims to the presidency of Galmudug state (VOA, 29 February 2020). ASWJ and Somali state forces had largely refrained from fighting each other since the signing of a peace accord in 2017.

Sustained political infighting has undermined the state’s ability to effectively counter the influence of Al Shabaab. Al Shabaab’s operational activities have been allowed to intensify, despite ongoing military support from the United States Africa Command (USAFRICOM) and African Union Mission to Somalia (AMISOM) peacekeeping forces, which had their mandate extended to 2021. Although attacks against civilians have not noticeably increased, Al Shabaab engagement in battles, as well as explosive and remote violence events, has risen substantially in the first half of 2020. Between January and July 2020, ACLED records a 49% increase in Al Shabaab-directed remote violence when compared with the first seven months of 2019. ACLED also records a 28% increase in the number of battles involving Al Shabaab.

Although an intensification of operations could also be associated with an attempt to exploit government vulnerabilities during the coronavirus pandemic, this would appear to be a secondary factor. Battles involving Al Shabaab were already at elevated levels in January, while Al Shabaab directed remote violence began an upward trend in February, with more events reported in the first half of March 2020 than the whole of March 2019. The first coronavirus case was not reported in Somalia until 16 March.

More than just an intensification of operations, Al Shabaab has also demonstrated an increasingly bold strategy in attacks targeting the upper echelons of government. Al Shabaab assassinated the state governors of Puntland-controlled Nugal and Mudug in suicide bombings in March and May, respectively. Meanwhile, the chief of the SNA, General Odawaa Yusuf Rageh, narrowly escaped an attempt in Mogadishu’s Hodan district in July. Although Al Shabaab has frequently orchestrated the targeted killings of military officers, an assasination attempt on such a senior military figure is unheard of in recent years (Africanews, 14 July 2020). The ability of Al Shabaab to orchestrate attacks on senior political and military figures highlights the operational strength of the group in 2020, but also exposes substantial state weaknesses exacerbated by political infighting across and between the Somali federal government and the various regional governments. Following the assassinations of the governors of Nugal and Mudug, the president of Puntland Said Abdullahi Dani went so far as to imply that Al Shabaab was being used by unspecified political actors within the government (BBC Somali, 22 May 2020).

In 2020, political turmoil, highlighted by the dismissal of Prime Minister Hassan Ali Khaire and ongoing uncertainty surrounding national elections, has undermined efforts to strengthen the Somali state and its security apparatus. At the same time, Al Shabaab has demonstrated its ability to intensify its general operations and to strike at the heart of government through targeted attacks on key political and military figures. Al Shabaab has capitalized on a state split by internal conflict, becoming increasingly bold in 2020.

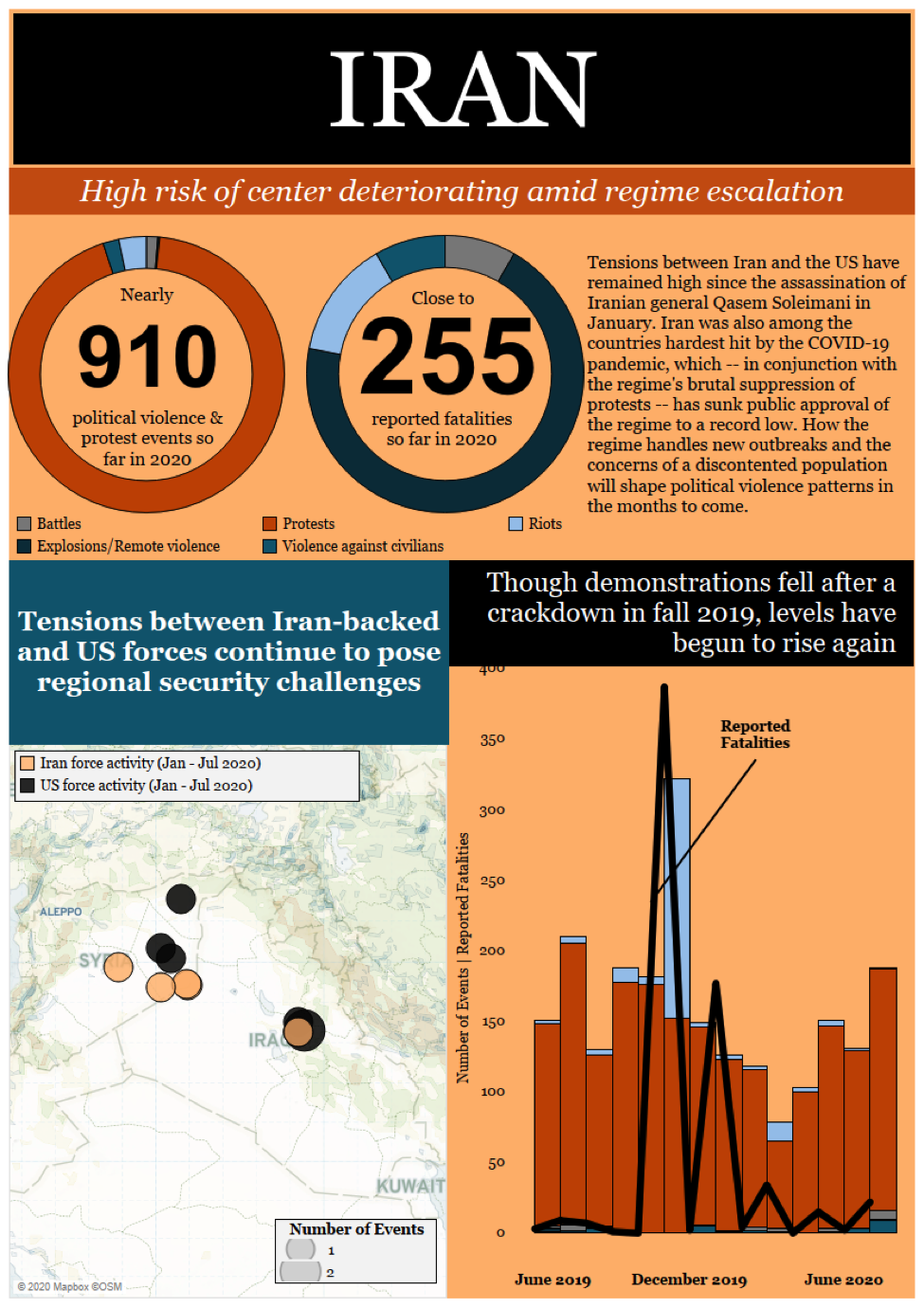

Further reading:

Tensions between Iran and the United States (US) have remained high since an American drone strike killed Qasem Soleimani, Commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) Quds Force, on 2 January 2020 in Baghdad. Yet, both sides have displayed reluctance to engage in full-scale armed conflict. Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, has more than once vowed retribution for Soleimani’s assassination, but apart from launching over a dozen missiles at two Iraqi bases hosting US troops in Anbar and Erbil on 8 January, the Iranian government has not further retaliated against the US. Debilitating sanctions, a currency in freefall, and fallout from the worst outbreak of coronavirus in the Middle East have likely all contributed to Iran’s reduced capability and desire to carry out a more significant response.

In the absence of open conflict, both Iran and the US have escalated regional tensions through more oblique actions. In the Persian Gulf, both the US and Iran have declared their intent to destroy any vessels that threaten their own (Voice of America, 23 April 2020). On 15 April, Iran conducted threatening maneuvers close to US ships (CENTCOM, 15 April 2020), and on 28 July fired a missile at a replica US aircraft carrier as part of a military exercise (Radio Farda, 28 July 2020). A similar exercise on 10 May resulted in a friendly fire incident that killed 19 Iranian sailors, dealing another embarrassing blow to Iran’s military after it accidentally downed a civilian aircraft on 8 January (The Guardian, 11 May 2020). The US has also engaged in provocative maneuvers of its own, though by air rather than sea. On 23 July, US fighter jets approached an Iranian passenger plane belonging to the US-sanctioned Mahan Air as it flew over southern Syria en route to Beirut. The flight was reportedly carrying members of Hezbollah and the IRGC. In response to the approaching fighter jet, the pilot of the passenger plane rapidly dropped altitude, causing some passengers to sustain injuries (USA Today, 23 July 2020; Al Jazeera, 24 July 2020). Meanwhile, since Soleimani’s killing, the targeting of US personnel and their allies by Iranian proxies in Iraq and Syria have increased, but the Trump administration’s inconsistent response to such attacks makes it difficult to predict the severity of a possible American retaliation (NPR, 16 April 2020).

Domestically, Iran has continued to face serious problems throughout the first 6 months of 2020: crippling sanctions, corruption, and the added pressures of the coronavirus have left the economy in ruins and its people increasingly disenchanted. As part of its campaign of “maximum pressure,” US sanctions targeting Iran’s crucial oil industry and its access to the international financial system have contributed to a projected 6% fall in Iran’s GDP and a continued inflation rate of over 30% (The National, 15 July 2020). Iran’s 2019 oil revenues were only a third of what they had been in 2018 and, if current patterns hold, the country may only reach 11% of its target revenue in 2020 (Radio Farda, 13 July 2020).

Still, US sanctions have not yet proven sufficient by themselves to extract significant concessions from Iran. Indeed, there are early signs that the Iranian government may look to sustain its own policy of “maximum resistance” through closer ties with China. In late June 2020, reports emerged of a potential strategic partnership between Iran and China worth $400 billion (Radio Farda, 29 June 2020). Though details remain vague, the deal could potentially throw a “lifeline” to the embattled Islamic Republic through massive economic and infrastructure developments, as well as cooperation on defense and intelligence sharing (Forbes, 17 July 2020).

The onset of the coronavirus pandemic, which hit Iran particularly hard (see this spotlight report from ACLED’s COVID-19 Disorder Tracker), has only aggravated the country’s already significant socio-economic problems. Iranian authorities blamed US sanctions for “severely hampering” their coronavirus response (Reuters, 14 March 2020). While US sanctions have contributed to a shortage of medical supplies, a more significant part of Iran’s pandemic-related troubles stem from long-standing issues of corruption and mismanagement by Iranian authorities themselves. One example of corruption at play is the recent discovery of a cover-up of reported coronavirus fatalities which was done in an effort to keep the population from demonstrating (BBC, 3 August 2020).

Apart from a spate of prison riots in March, there has been little serious unrest directly related to the coronavirus, yet the number of protests have continued to climb since pandemic-related restrictions were lifted in late March and early April. This is but one indication pointing to record-low confidence and support domestically for the Islamic Republic. Coming on the heels of a violent crackdown on mass demonstrations across Iran in late 2019, the turnout for the 2020 parliamentary elections in February was 25% in Tehran and 42% overall, the lowest levels since the 1979 Islamic Revolution (Reuters, 23 February 2020). The Iranian government has indicated it would put down any renewed unrest with equal severity. On 16 July, when an anti-government protest broke out in the city of Behbahan, authorities responded swiftly with mass arrests and a promise by police to deal “decisively” with any further protests (Al Jazeera, 17 July 2020). The recent confirmation of several death sentences for those who protested in late 2019 underscores the extreme measures Iran is willing to employ to quell any potential domestic unrest.

Finally, as predicted, the nuclear standoff has continued. Following the US government’s unilateral withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) and its re-imposition of sanctions in 2018, Iran began violating its commitments under the deal. Of significance is the mysterious blast that struck Iran’s primary uranium enrichment center in Natanz on 3 July, causing enough damage to potentially set the site back by as much as two years (New York Times, 10 July 2020). A previously unknown group of domestic dissidents calling itself the “Cheetahs of the Homeland” claimed responsibility for the explosion. However, this group could also be a hoax or deliberate misdirection designed by foreign agents (Newsweek, 13 July 2020). This incident, together with several fires and explosions at other Iranian military and industrial sites, has led to speculation of a new round of foreign sabotage attacks (Radio Farda, 24 July 2020). If these suspicions are confirmed, it may indicate a return by the US and Israel to the use of clandestine sabotage operations in the vein of Stuxnet to cripple Iran’s nuclear capability. This tactic also presents certain risks and may end up pushing Iran’s nuclear program further underground in the long term (New York Times, 10 July 2020).

Further reading:

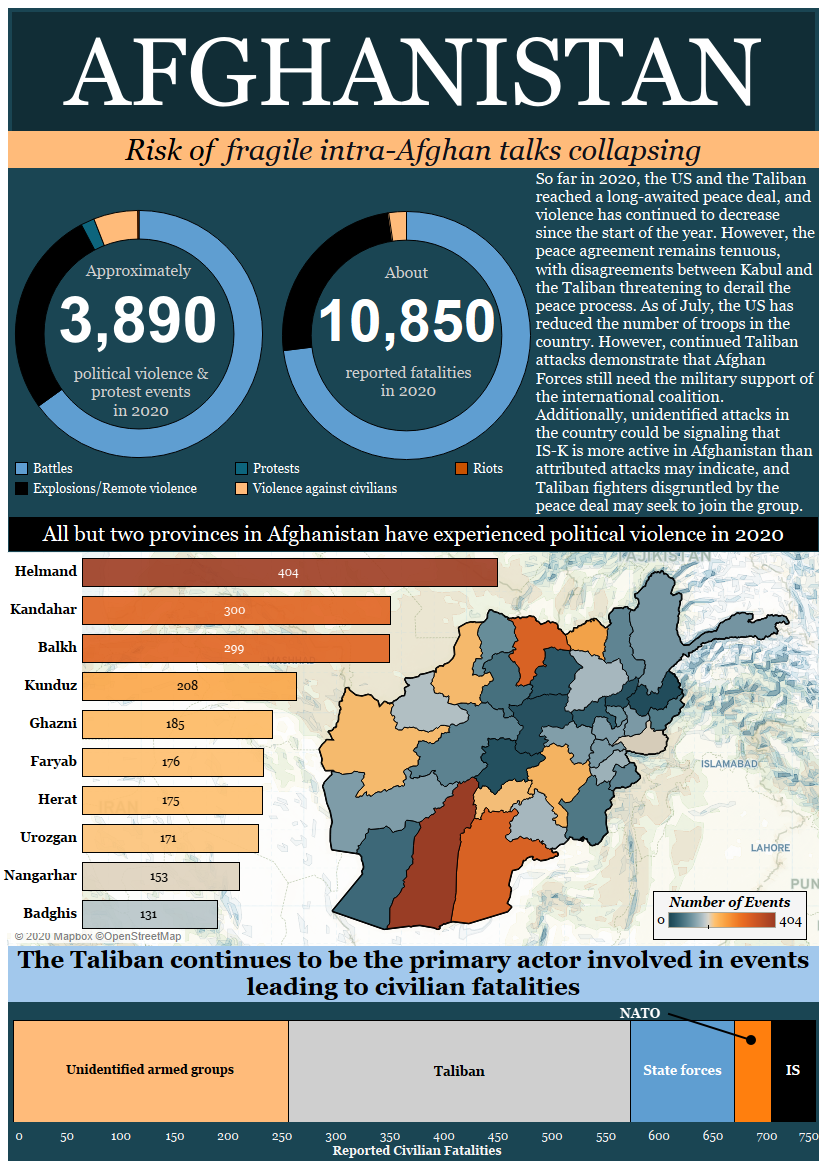

In February 2020, the US and the Taliban finally signed a long-awaited peace deal in Afghanistan amid a decline in violence. The US had initially withdrawn from peace negotiations following a period of lethal battles from June 2019 to September 2019. The February peace deal provided for the gradual withdrawal of American troops from Afghanistan, as well as an end to Taliban attacks against the US. The agreement also entailed a prisoner exchange between the Taliban and Afghan government in order to start intra-Afghan talks (for more, see ACLED’s report on the US-Taliban peace deal).

In accordance with the peace deal, the US reduced the number of troops in Afghanistan from 13,000 to 8,600 and pulled out from five bases. Further withdrawals are expected by November. However, the withdrawal could be slowed by an amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA). The amendment would block the removal of further troops if the Trump administration does not provide clarification about an alleged Russian bounty program, which claims that Russian intelligence paid the Taliban to kill US soldiers in Afghanistan (The Hill, 1 July 2020; New York Times, 26 July 2020).

Meanwhile, the Taliban ceased operations against US and NATO forces, yet continues to target Afghan forces. Taliban attacks against Afghan forces significantly increased in March 2020, even as the Afghan government reduced its offensives against the Taliban. By May, however, the Taliban announced a three-day truce during Eid Al Fitr, reopening space for the stalled intra-Afghan negotiations. While Taliban attacks resumed after the truce, prisoner exchanges continued — even during one of the deadliest weeks, from 15 to 21 June, where over two hundred Afghan security forces were killed by the Taliban. These developments indicate that both parties still desire to end the decades-long war. This was further evidenced by the Taliban’s decision to announce another three-day ceasefire for Eid al Adha, starting on 31 July. Immediately following the truce, prisoner exchanges were completed, though the Afghan government refused to release some prisoners due to their criminal records. However, Afghanistan’s assembly of elders (Loya Jirga) ruled for the release of remaining prisoners, paving the way further for the intra-Afghan talks.

Meanwhile, the political landscape of Afghanistan has also changed significantly since the start of the year. In May 2020, President Ashraf Ghani and his rival Abdullah Abdullah signed a power-sharing agreement, eight months after the controversial presidential election that was marred by allegations of fraud. The agreement gives Abdullah and his coalition half of all cabinet appointments and names him the chairman of the High Council for National Reconciliation, the group which will take charge of the peace negotiations with the Taliban (Reuters, 23 March 2020; New York Times, 17 May 2020).

Still, despite signs of progress toward peace, civilians have often faced the brunt of the violence, as ACLED projected at the start of the year. Fighting between Taliban and Afghan forces resulted in hundreds of civilian casualties during the first half of the year, with both parties blaming the other for targeting civilians. From 1 January to 1 August, armed groups or Afghan forces targeted civilians over 280 times. The two ceasefires around Eid al Fitr and Eid al Adha led to a decline in the number of civilians killed over several days. However, the number of overall civilian fatalities remains at similar levels to the same period in 2019. Going forward, a potential peace deal between the Afghan government and the Taliban could lead to a further decrease, whereas a re-escalation of hostilities will likely reverse these trends.

At the same time, the Islamic State Khorasan province (IS-K) — the Islamic State affiliate in Afghanistan that was dealt a significant defeat last year in Nangarhar — has claimed responsibility for multiple attacks, particularly targeting Shiite Muslims. Civilians, including religious scholars, government workers, judges, and lawyers, were also attacked by unidentified actors, almost twice as often as the same period of 2019. IS-K may be conducting such attacks, as the group still retains significant capacity for violence around the country, albeit at a smaller scale oriented around sleeper cells. Moreover, the group’s capabilities could also be boosted by the possibility of disgruntled Taliban fighters, who oppose the peace deal, joining IS-K (PBS, 26 February 2020). The latest attack of the group on 26 July aimed to release IS-K inmates from Jalalabad Prison and continued for 20 hours, proving that the group still has the capacity to launch complex attacks and seeks to reinforce its fronts. However, if intra-Afghan talks progress, it is likely that both sides — along with the US — would unite against IS-K as they have in the past, with all parties viewing it as a major threat to peace.

Lastly, the humanitarian situation in the country has been further complicated by the coronavirus pandemic. As the country lacks sufficient medical infrastructure and testing capacity, the low number of confirmed cases likely obscures the scale of the problem (The Diplomat, 3 June 2020). Partial border closures with neighboring countries have disrupted imports, increasing essential food prices (Reuters, 1 April 2020). The crisis has also provided the Taliban an opportunity to present itself as a legitimate actor by launching a campaign to combat the pandemic (for more, see this spotlight report from ACLED’s COVID-19 Disorder Tracker). The campaign includes raising awareness, providing medical and protective material, and cancelling gatherings in areas under its control — although the group refused to declare an outright ceasefire amid the pandemic. Additionally, clashes between Afghan forces and the Taliban continue to inflict collateral damage to medical facilities and personnel. Meanwhile, the coronavirus has reportedly spread through the Afghan army, potentially undermining its capacity to respond to Taliban assaults (VOA, 4 July 2020). The international community has increasingly been providing medical support since the beginning of the crisis, but as the ongoing violence keeps Afghan society vulnerable to such emergencies, the virus is unlikely to be contained in the near future.

Further reading:

- The US-Taliban Peace Deal: 10 Weeks On

- Security Incidents in Afghanistan: February-March 2020

- The Taliban: 2018 & 2019

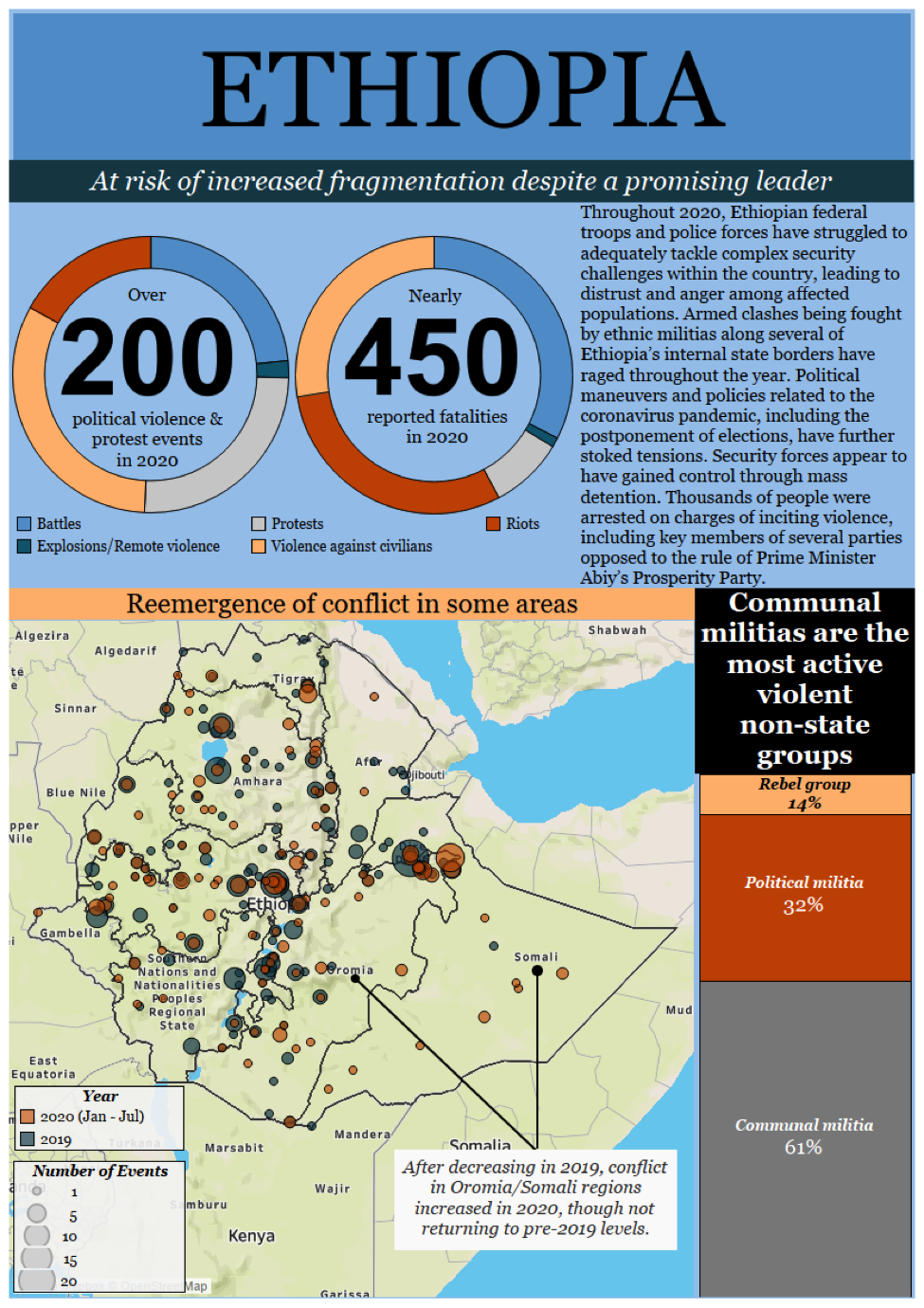

In January, ACLED warned that Ethiopia was at risk of increased fragmentation despite a recent change in government applauded by the international community. Simmering political tensions heightened by delayed elections and a weak security apparatus have exploded in recent weeks across Ethiopia’s ethnically-based federal states in a string of deadly riots, ethnic killings, and mass arrests of political opposition leaders.

Throughout 2020, Ethiopian federal troops and police forces have struggled to adequately tackle complex security challenges within the country, leading to distrust and anger among affected populations. Armed clashes being fought by ethnic militias along several of Ethiopia’s internal state borders have raged throughout the year, leading to the displacement of hundreds of thousands (OCHA, 30 June 2020). Failure to recover kidnapped students (New York Times, 30 January 2020), inconclusive investigations into a series of high-profile assassinations (International Crisis Group, 3 July 2020), and accusations of serious human rights violations perpetrated by federal forces (Amnesty International, 29 May 2020) have all contributed to concern that Ethiopia’s current government is ill-equipped to handle the complicated security environment that the country’s ethno-federalist system entails.

Political maneuvers and policies related to the coronavirus pandemic in the country’s capital Addis Ababa have further stoked tensions. Following a vote by lawmakers to postpone national elections until after the coronavirus is deemed to no longer be a threat (Al Jazeera, 10 June 2020), opposition parties insisted that a coalition government be formed instead of allowing the prime minister to continue to lead. One opposition party accused the government of having no genuine interest in holding elections and submitted that Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed was using the coronavirus pandemic as “an excuse to establish a one-man dictatorship” (Reuters, 5 May 2020). The speaker of the house, a member of the ruling party in Ethiopia’s Tigray region, resigned, saying that she “refuses to work with a group that violates the constitution on a daily basis and promotes dictatorship” (BBC Amharic, 8 June 2020).

Tensions stoked throughout the year exploded on 29 June following the assassination of a popular Oromo musician in the capital by unknown gunmen. The assasination was promptly positioned within a long history of ethno-nationalist political violence in Ethiopia, and an entrenched narrative of marginalisation within the Oromo community. Within hours, violent riots engulfed cities and towns across Oromia regional state, with mobs of Oromo youth clashing with police and rival groups. Security forces were reportedly unable to contain the violence and stood by as ethnic and religious minorities were killed and their businesses torched around the region. Intense crackdowns and street battles ensued, leaving over 230 people dead (Washington Post, 8 July 2020).

As the country reels from the latest bout of violence, security forces appear to have gained control through the use of mass detention and violent repression. Thousands of people were arrested on charges of inciting violence, including key members of several parties opposed to the rule of Prime Minister Abiy’s Prosperity Party (Addis Standard, 2 July 2020). With key opposition party members jailed, national elections delayed, and ethnic tensions at an all-time high, Ethiopia faces serious risks of widespread political violence escalating during the second half of 2020.

Further reading:

- Ethiopia Sourcing Profile

- Bad Blood: Violence in Ethiopia Reveals the Strain of Ethno-Federalism under Prime Minister Abiy

- Change and Continuity in Protests and Political Violence in PM Abiy’s Ethiopia

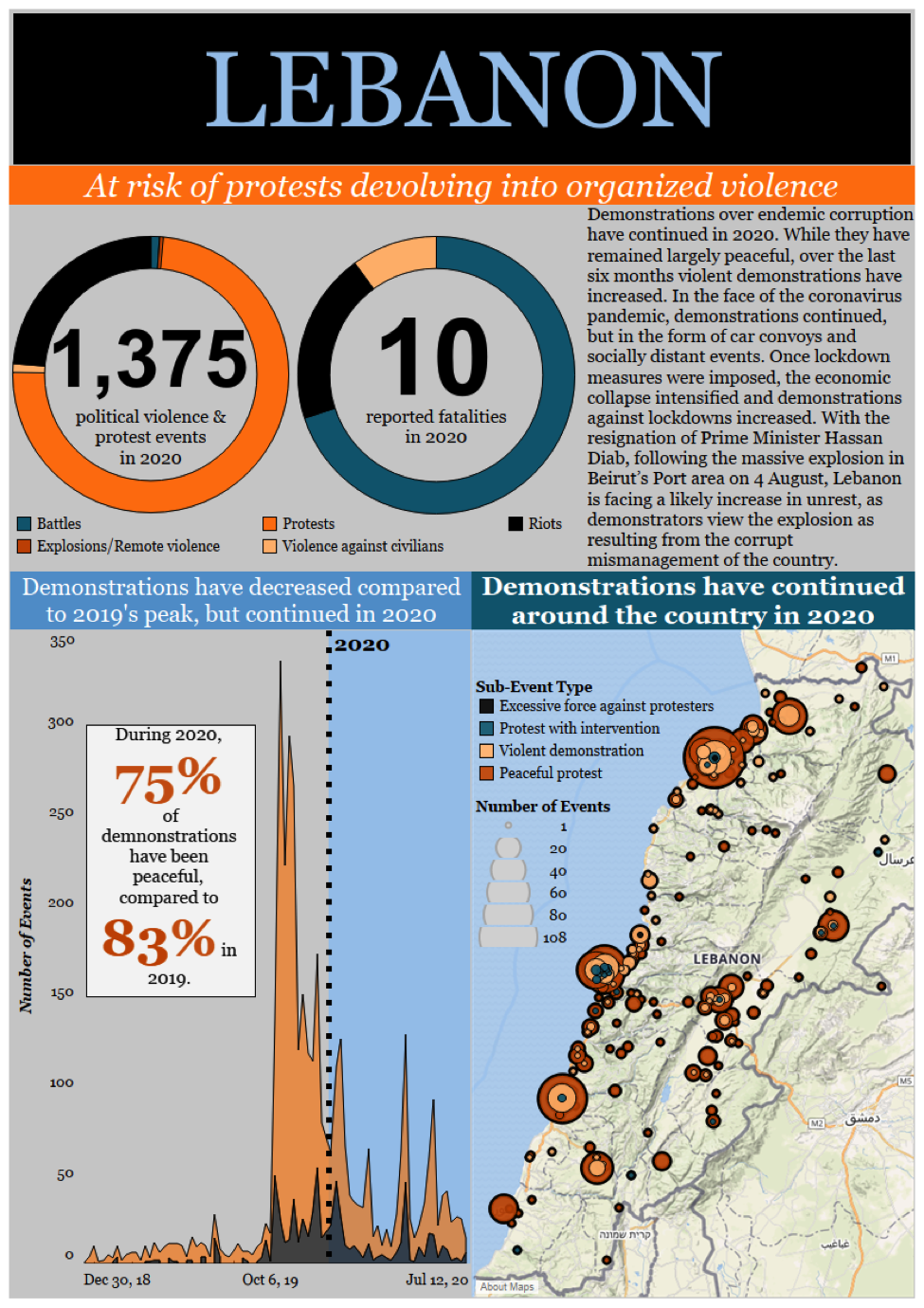

While the coronavirus pandemic significantly impacted Lebanon’s existing political and economic crisis, the massive explosion which ripped through Beirut’s Port area on 4 August, reportedly caused by the faulty storage of ammonium nitrate, is expected to push the country even further towards economic collapse. Prime Minister Hassan Diab, who has been leading the government since January 2020, resigned on 10 August, together with the entire government. He noted that the explosion was a direct result of endemic corruption (Al Jazeera, 10 August 2020). Now, however, with no one in charge of the spiraling crisis, Lebanon is tasked with finding its third Prime Minister within the span of a year (CNN, 11 August 2020).

While demonstrations had remained largely peaceful, over the last six months, violent demonstrations and mob violence, especially following the explosion, have increased.1 In light of ACLED’s August data pause, data including post-explosion events will be available in September. From the start of the nationwide demonstration movement in October 2019 to the end of 2019, roughly 19% of all demonstrations were accompanied by some form of violent rioting. This number has increased to approximately 33% from the beginning of 2020 through the end of July. As frustrations have grown, bank branches have been bombed and burned down, and one protester was reportedly killed in Tripoli in May by live fire from Lebanese security forces (New York Times, 10 May 2020). In the days immediately after the 4 August explosion, violent clashes ensued as demonstrators grew furious over the corruption, mismanagement, and negligence of the ruling elite that led to the disaster (New York Times, 8 August 2020).

The value of the Lebanese pound compared to the US dollar has crashed over the last year. It has lost approximately 75% of its original value since October (Al Jazeera, 23 June 2020). Inflation is increasing and the prices of food and basic needs have risen by approximately 55% (Financial Times, 15 June 2020). In June 2020, the Prime Minister announced that they were seeking a $10 billion loan from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to get the economy back on track (CNBC, 23 June 2020). However, on 20 July, it was reported that talks with the IMF had halted (Washington Post, 20 July 2020). Just before announcing the economic rescue plan involving the IMF, Lebanon was unable to make a $1.2 billion payment for foreign bonds for the first time since its establishment (New York Times, 10 May 2020).

As the coronavirus made its way to Lebanon, demonstrations continued, but in the form of car convoys and socially distant events. Once lockdown measures were imposed, the economic collapse intensified and demonstrations against lockdowns increased. The impact of the coronavirus pandemic is estimated to raise poverty levels from 30% in 2019 to around 45% or more by the end of 2020 (EUROMESCO, June 2020). Also fuelling frustrations is the ever-rising unemployment rate in Lebanon. By June 2020, the rate was above 30% and is only expected to continue to rise (Consultancy ME, 30 June 2020).

In recent months prior to the explosion, demonstrations shifted away from the initial calls for a new political system and toward concerns about resource shortages, particularly electricity. Frustrations over the rationing of electricity ran high, as many areas only receive a few hours of electricity a day (Washington Post, 20 July 2020). The explosion has only further exacerbated the issue as two of the main water and electricity stations were heavily damaged. The explosion compromised much of the capital city’s infrastructure, leaving 300,000 citizens without shelter (Al Jazeera, 5 August 2020). It likewise almost entirely destroyed the port area which handles 80% of Lebanon’s imports and houses the country’s main grain silo (Time, 5 August 2020). At least four hospitals were damaged extensively in the blast and have had to turn away patients (Forbes, 5 August 2020).

A total of 20 people have so far been detained in relation to the 4 August blast, including the head of Lebanon’s customs department, his predecessor, and the head of Lebanon’s port (Global News, 10 August 2020). Lebanon currently faces the worst financial crisis since the civil war, the coronavirus outbreak has spiked in recent weeks, and it is now confronted with the additional challenge of rebuilding the capital city, estimated to cost billions of dollars (Business Insider, 6 August 2020). The effects of the seismic blast that rocked Beirut are expected to have a significant impact on Lebanon’s economy and may lead to a shortage of food within the next two months (Forbes, 5 August 2020). While it is unclear how Lebanon will cope going forward, it is likely that the explosion, seen to have resulted from the same mismanagement and corruption that sparked the protest movement last year, will lead to even further unrest.

Further reading:

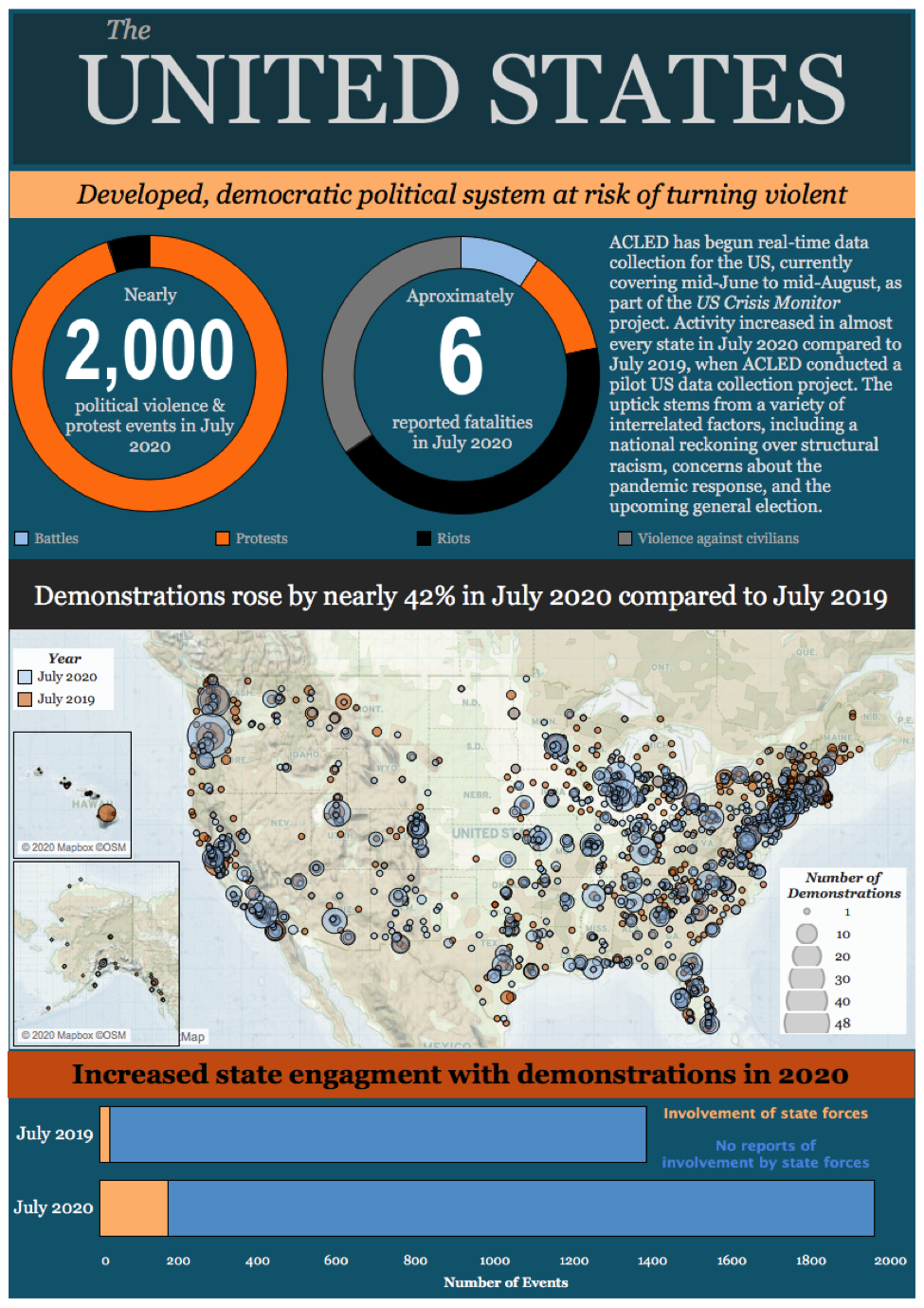

At the start of the year, a range of indicators warned that America faced increasing risks of political violence and instability: mass shootings had hit record highs (BBC, 29 December 2019), violent hate crimes were on the rise (Al Jazeera, 13 November 2019), and police killings were continuing unabated, at 2.5 times the rate for Black men as for white men (FiveThirtyEight, 1 June 2020; Nature, 19 June 2020). Polling data pointed to skyrocketing levels of political polarization (New York Magazine, 23 January 2020), and thousands of protests had been reported across the country during the previous year.

Within a matter of months, these existing risks were compounded by the social and economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic and an unprecedented wave of demonstrations sparked by the police killing of George Floyd. Both developments have shattered the status quo ahead of the 2020 general election, simultaneously creating profound opportunities for change alongside new flashpoints for state repression, extremist attacks, militia clashes, and other forms of political violence.

To track these trends, ACLED has partnered with the Bridging Divides Initiative at Princeton University to launch the US Crisis Monitor — a special project to collect data on political violence and demonstrations across all 50 states and DC in real time. The project builds on the pilot project we conducted this time last year, which informed our assessment in the original installment of this report series: that America was at heightened risk of violent political instability ahead of this year’s election in November. Comparing the pilot data for July 2019 with the latest US Crisis Monitor data for July 20202At time of writing, ACLED has collected a full month of data for July 2019 (during the pilot project) and July 2020 (publicly available through the current US Crisis Monitor project). illustrates the current scale of social mobilization and demonstrates that these risks have only grown over the past 12 months.

While the US has long been home to a vibrant protest environment, demonstrations surged to new levels in 2020. During last year’s three-month pilot period, ACLED recorded more demonstrations in the US than in almost any other country covered in the dataset,3Over three months from July through September, ACLED collected data on approximately 3,200 demonstration events in the US — second only to India, which has four times the American population. with nearly 1,400 events in July 2019 alone. Even still, the number of demonstrations increased by 42% to nearly 2,000 events in July 2020, driven by a massive spike in protests associated with the Black Lives Matter movement following the killing of George Floyd.4The number of demonstrations in late May and June, in the immediate aftermath of Floyd’s killing, are even higher.

Although the vast majority of demonstrations in July 2020 were peaceful, state intervention has increased since this time last year. Last July, under 2% of all demonstrations — fewer than 30 events — were met with intervention by police or other authorities.5 This includes all events involving state forces, either as a primary actor or as an associated actor. This July, that number swelled to nearly 9% — or over 170 events — despite the fact that more than 95% of all demonstrations were non-violent. Government personnel used force in just three of these engagements in July 2019, whereas, in July 2020, they used force against demonstrators in at least 65 events. Such force includes, but is not limited to, the use of less-lethal weapons like tear gas, rubber bullets, and pepper spray, as well as beating with batons. In addition to demonstrators, state forces have also targeted journalists reporting on the unrest (US Press Freedom Tracker, 12 June 2020), and ACLED records nine events in which state personnel used force against journalists in July 2020 alone.6The majority of these events occurred in Portland, Oregon.

The escalating use of force against demonstrators comes amid a wider push to militarize the government’s response to domestic unrest, and particularly demonstrations perceived to be linked to left-wing groups like ANTIFA, which the administration views as a “terrorist” organization (New York Times, 31 May 2020). In the immediate aftermath of George Floyd’s killing, President Donald Trump posted a series of social media messages threatening to deploy the military and National Guard to disperse demonstrations, suggesting that authorities should use lethal force if demonstrators engage in looting (New York Magazine, 1 June 2020). Rhetoric soon translated into policy: in early June, the government used National Guard troops, Secret Service agents, and US Park Police — among other federal agents — to violently disperse peaceful protests in Lafayette Square outside the White House to create a photo opportunity at St. John’s Church (Vox, 2 June 2020; New York Times, 10 June 2020). By the end of the month, the president issued an executive order authorizing federal agents to pursue demonstrators who pull down statues or damage federal property, spurring the creation of the Protecting American Communities Task Force (PACT)7 PACT was established to protect “American monuments, memorials and statues” and is directed to “conduct ongoing assessments of potential civil unrest or destruction and allocate resources to protect people and property … [which may] involve potential surge activity to ensure the continuing protection of critical locations” (DHS, 1 July 2020). and the deployment of Department of Homeland Security (DHS) agents around the country, including in Portland, Seattle, and Washington, DC (Al Jazeera, 23 June 2020). In Portland, reports indicate that DHS personnel used excessive force and arbitrarily detained demonstrators in unmarked vehicles far from their area of operations at the city’s federal courthouse — a potentially illegal practice that was recently emulated by the New York Police Department during a demonstration in Manhattan (The Guardian, 29 July 2020). Since George Floyd’s killing, dozens of federal and National Guard deployments have been reported across the country, including members of PACT as well as forces affiliated with Operations Legend and Diligent Valor.8ACLED codes federal and National Guard deployments as “Strategic developments” due to their potential impact on future patterns of political violence and/or demonstrations. “Strategic developments” are not systematically coded like other ACLED events, however, so they are not cross-context and -time comparable and should not be used for the same types of analysis. Check the US Crisis Monitor FAQ page for more information on “Strategic developments” and how to use them in the American context.

Government forces are not the only actors intervening in demonstrations, however. Amid rising tensions and deepening mistrust in state institutions, militias and other non-state actors are increasingly engaging with demonstrators directly. In July 2020, ACLED records over 30 events in which non-state actors intervened in demonstrations — up from zero in July 2019. These actors include organizations and militias from both the left and right side of the political spectrum, such as Antifa, the “Not Fucking Around” Coalition, the New Mexico Civil Guard, the Patriot Front, the Proud Boys, the Boogaloo Bois, and the Ku Klux Klan, to name a few. Additionally, individual perpetrators have committed car-ramming attacks targeting demonstrators around the country, with at least 13 such incidents reported just in July 2020.9Events categorized as car rammings are those in which a car was driven into protesters on purpose, or is under investigation due to suspicion of purposeful intent (with the event updated if/when new information comes to light). This means that events in which a car accidentally hits protesters (e.g. a car is surrounded at an intersection, slowly rolling forward) are not categorized as such here. For more, see the US Crisis Monitor FAQ page.

There is also a growing presence of armed individuals at demonstrations: more than 20 such incidents were reported in July 2020. This trend threatens to more quickly escalate confrontations between protesters and counter-protesters into violent clashes, which are occurring with increased regularity. In July 2019, only 17 counter-protests were reported around the country, or approximately 1% of all demonstrations, and only one of these allegedly turned violent. In July 2020, ACLED records over 160 counter-protests, or more than 8% of all demonstrations. Of these, 18 turned violent, with clashes between pro-police demonstrators and demonstrators associated with the Black Lives Matter movement, as well as demonstrators for and against COVID-19 restrictions.

While these data present only a snapshot of American disorder, the trendlines are clear: demonstrations have erupted en masse around the country, and they are increasingly met with violence by state actors, non-state actors, and counter-demonstrators alike. In addition to traditional election-year debates, the country faces deep divisions over racial inequality, the role of the police, and economic hardship exacerbated by an ineffective pandemic response. The administration has taken multiple steps to inflame these tensions, from announcing further federal deployments in “Democrat-led cities” like Chicago and Albuquerque (AP, 22 July 2020) to threatening a postponement of the election altogether (BBC, 30 July 2020). In this hyper-polarized environment, state forces are taking a more heavy-handed approach to dissent, non-state actors are becoming more active and assertive, and counter-demonstrators are looking to resolve their political disputes in the street. All of these risks will intensify in the lead-up to the vote, threatening to boil over in November if election results are delayed, inconclusive, or rejected as fraudulent.

To keep track of these risk factors in real time, check the US Crisis Monitor. Updated weekly, the data and crisis mapping tool are freely available for public use. Data dating back to the beginning of the current Black Lives Matter movement in May will be released by the end of August. The project seeks continued funding to ensure that data collection continues through the 2020 election and beyond. If you are interested in supporting this work, please contact [email protected].

© 2020 Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). All rights reserved.