Balochistan, home to a majority ethnic Baloch population, is the largest and least populous province of Pakistan. Rich in natural mineral resources and gas reserves, Balochistan is also the country’s least urbanized and most impoverished province. Despite an abundance of natural resources, and major investment through the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), both the province and the Baloch community have struggled to receive an equitable share of the benefits derived from these assets (Gandhara, 15 June 2019). Mainstream Baloch politicians have strived for greater autonomy and control over resources. At the same time, armed separatist groups demand full independence for the province. Various separatist groups have been battling Pakistani security forces since 1948 in the longest running insurgency in the country. Since the beginning of 2020, ACLED records a rise in organized political violence events1Organized political violence events are inclusive of Battles, Explosions/remote violence and Violence against civilians events in the ACLED dataset.involving armed Baloch separatist groups. The rise in events has been preceded by greater unity among Baloch separatist groups, the formation of trans-province alliances between Baloch separatist groups and other separatist groups, and increased exploitation and repression of Baloch civilians by Pakistan’s military during security operations in Balochistan. These three factors, along with the rise in violence, suggest a possible resurgence of the Baloch separatist movement.

Post-2015 Decline in Baloch Separatist Violence

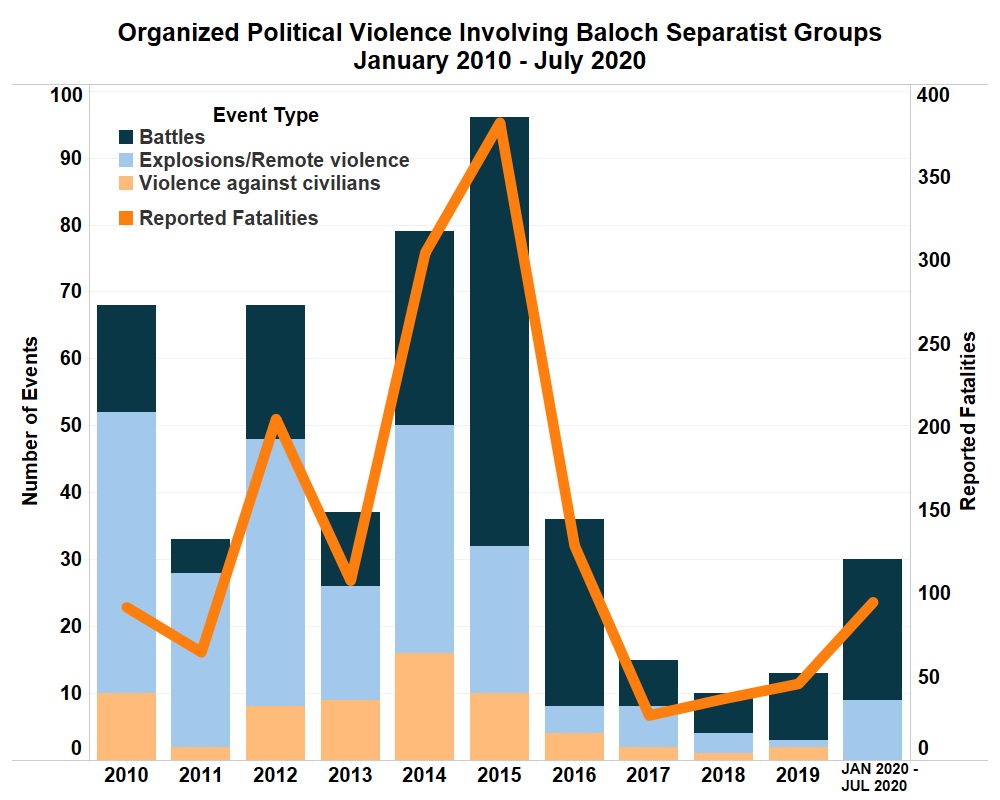

While the struggle for Baloch independence has its roots in the immediate aftermath of the independence of Pakistan in 1947, the current insurgency began in early 2000 to challenge the central government’s control over the province, and, in particular, the state and military’s exploitation of the province’s resources. From 2010 to 2015, organized political violence events linked to the insurgency gradually increased, peaking in 2015 with 96 events and 383 total reported fatalities for the year (see figure below). After 2015, organized political violence events involving Baloch militants steadily decreased. From 2017 to 2019, ACLED records 38 events with 110 reported fatalities (see figure below). Compounding decades of counterinsurgency operations and government amnesty schemes, discord among Baloch militant groups, and a lack of leadership contributed to the insurgency’s decline (Firstpost, 26 January 2019; Gandhara, 18 April 2019).

The decline in Baloch militant violence after 2015 can be partly explained by the Pakistani government’s launch of a two-pronged approach to counter the insurgency that year. Security forces intensified counterinsurgency operations in the region and introduced an incentive-based disarmament and rehabilitation program for Baloch militants. Counterinsurgency operations intensified across the nation after the introduction of the National Action Plan (NAP). The NAP was a counterinsurgency policy initiative aimed at curbing militancy around the country following the December 2014 attack by the Islamic militant group Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) on the Army Public School in Peshawar city, which killed 141 civilians, including 132 school children. After two years of continued counterinsurgency operations, the Pakistani government claimed to have subdued militancy in the country, including the Baloch insurgency. The state claimed that militants were either on the run or laying down their arms under the government’s amnesty scheme, which involved financial rewards. Reportedly, over 1,025 Baloch militants surrendered under the amnesty scheme through August 2016 (Geo TV, 29 August 2016).

Additionally, internal divisions among Baloch separatist groups and the death of prominent Baloch leaders led to a weakening of the groups. The death of long-time nationalist leaders such as Nawab Khair Bakhsh Marri, who provided an ideological platform for Baloch armed movements, and was credited by many for inspiring the latest wave of Baloch militancy (BBC, 11 June 2014), created a leadership gap for the insurgency. Marri, who was a key insurgent leader during the 1970s in Balochistan, led the oldest and largest armed group, the Baloch Liberation Army (BLA) (Dawn, 11 June 2014). Following his natural death in 2014, disagreement between his sons over succession led to two of his sons spearheading two different armed groups, the BLA and the United Baloch Army (UBA). Reports suggest there were two distinct divisions among the most active separatist groups, one aligned with the BLA and the other aligned with Baloch Liberation Front (BLF), including the UBA (Stratagem, 2017).2The BLF, currently led by Dr. Allah Nazar, is a trans-national Baloch organization that was first founded by Juma Khan Marri in Syria in 1964. It first became active in Pakistan in the 1970s. Mainly based in Balochistan’s Makran region, it is one of the oldest separatist groups and, together with the BLA, it is one of the most active groups since the latest insurgency began in early 2000. While the separatist groups have the shared goal of establishing Baloch independence, the rivalry between the BLA and BLF has occasionally led to internecine armed clashes (Stratagem, 2017). Furthermore, the death of unifying leaders, such as Manan Baloch of the Balochistan Nationalist Movement (BNM), during operations by security forces in 2016 dealt a setback to the insurgency’s common goals. Manan Baloch was reportedly the brains behind efforts to reorganize fragmented separatist factions and mend relations between the rival BLF and BLA (Gandhara, 2 February 2016).

Resurgence of Baloch Separatist Violence in 2020

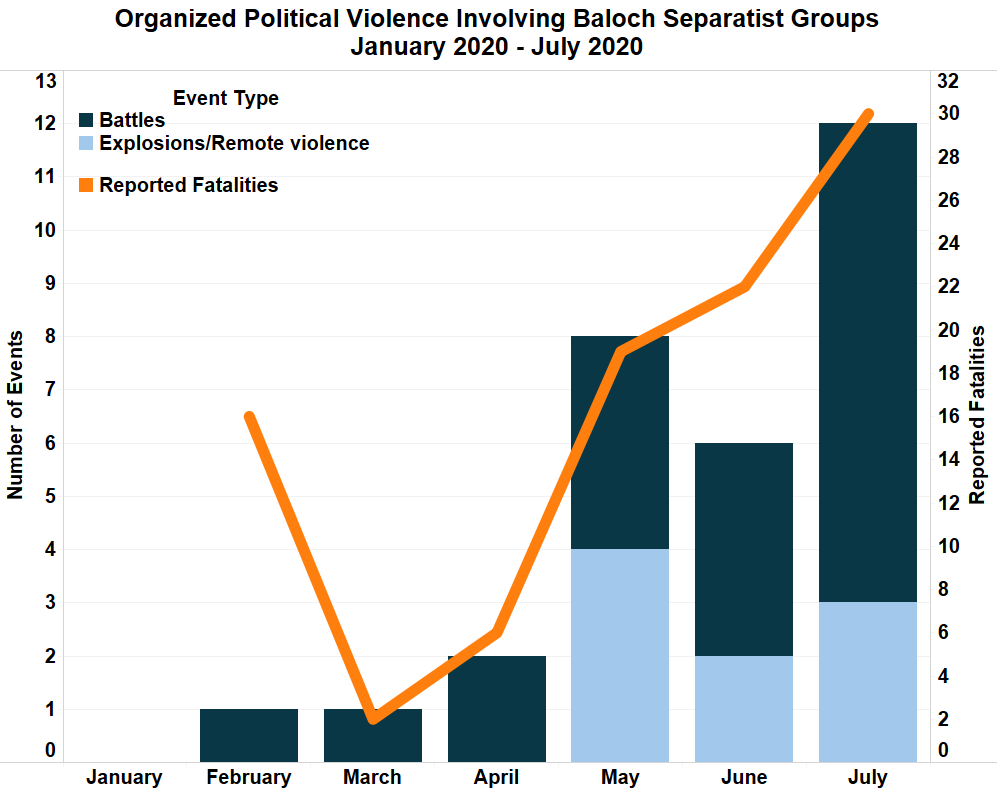

After a long period of decline, organized political violence involving Baloch separatist groups has increased during the first seven months of 2020. As of 31 July, ACLED records 30 organized violent events involving Baloch separatists and 95 fatalities this year (see figure below).

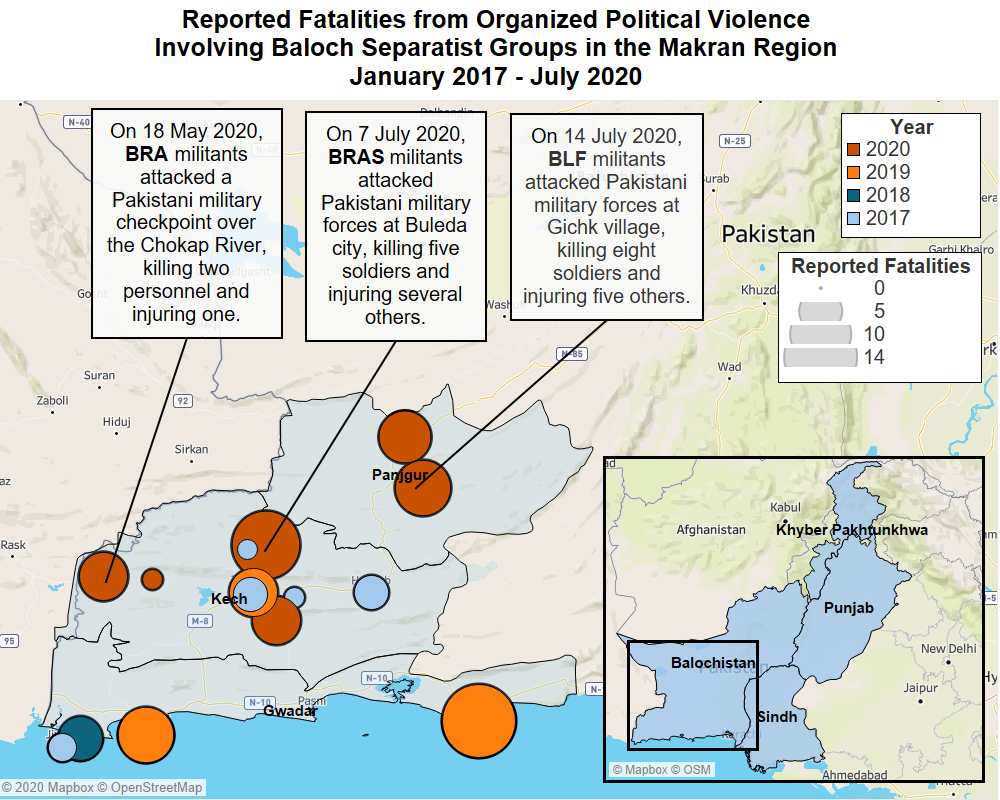

Of these 30 events, 13 took place in the Makran region of Balochistan, reportedly causing 40 fatalities (see map below). Until 2019, despite occasional attacks, the insurgency was reported to be substantially weakened in the Makran region, which consists of the districts of Kech, Panjgur, and Gwadar (Gandhara, 18 April 2019). Additionally, of the total fatalities from events involving Baloch separatist groups in the first seven months this year, nearly 75% of fatalities were security personnel.3The breakdown of fatalities was obtained from analysis of the ACLED event notes. ACLED does not code fatalities by actor category in separate columns within the dataset. When reported, the identity of the fatalities is included in the event notes. The increase in events involving Baloch militants — particularly in regions where separatists were thought to be weak — and high fatalities among security forces point towards a possible resurgence of the Baloch separatist movement.

One of the primary reasons for the resurgence of the Baloch insurgency in the region is the better coordination among the most active Baloch groups. As noted, in recent years, rivalries among Baloch militant groups have often been cited as a cause for the insurgency’s decline (Firstpost, 26 January 2019; Gandhara, 18 April 2019). However, in November 2018, an official alliance of three Baloch militant groups, the Baloch People Liberation Coalition [Baloch Raaji Ajoi Sangar] (BRAS)], was announced (Terrorism Monitor, 20 September 2019). The BRAS is an alliance between the Baloch Republican Army (BRA), and former rivals BLF and BLA (see Appendix below). The formal alliance between two of the largest Baloch armed groups, the BLA and BLF, signaled that militants were regrouping and joining forces to conduct coordinated operations against the Pakistani government.

Secondly, the recent operational alliance with militant groups from Sindh province could be a factor in the increased frequency of attacks. On 29 June, members of the BLA attacked the Pakistan Stock Exchange in Karachi city of Sindh province, killing four security personnel. Claims made by security forces, as well as an admission by the BLA following the attack, indicate that Baloch militants have managed to form alliances with Sindhi secessionist militant groups such as the Sindhudesh Revolutionary Army (SRA) (Arab News, 13 July 2020). In late July, BRAS officially announced an operational alliance with SRA, a Sindh-based militant outfit aiming to establish an independent homeland for Sindhis, the native ethnic group of Sindh province. The SRA has claimed four attacks against security personnel so far in 2020. While operational engagement between Baloch and Sindhi militant groups is not new, the official confirmation of the alliance could mean coordination around identifying strategic targets and expansion of operational areas. In the past, both Baloch and Sindhi militant groups have targeted Chinese interests in Pakistan. The groups have opposed Chinese projects and investment in Sindh and Balochistan, alleging the projects exploit the natural resources of both the provinces and are likely to bring about demographic change that would increase the number of people from ethnic groups other than Baloch and Sindhi groups in the respective provinces (Guardian, 30 May 2016). With the establishment of a formal alliance, continued attacks on security forces and Chinese interests in both Sindh and Balochistan provinces seems likely.

The current rise in Baloch militant violence can also be explained by a cycle of reprisal killings. In May 2020, a series of targeted attacks in Balochistan killed 17 security personnel. Baloch militants claimed that the attacks were retaliation for the Pakistani military’s operation in Kech district and the alleged repression of Baloch civilians during the security operation (Hindustan Times, 9 May 2020). Following the attacks, security forces launched “Ground Zero Clearance Operation” in areas close to the border with Iran (Arab News, 5 June 2020), targeting militants active in the districts of Kech, Panjgur, and Gwadar. Following the launch of the operation in early June, a spike in organized political violence events and fatalities were reported. From June until the end of July, ACLED records 18 organized political violence events involving Baloch militant groups with 52 fatalities. Violence is expected to further escalate as security forces intensify operations following the previously noted BLA attack on the Pakistani Stock Exchange in Karachi on 29 June.

In addition to the security operations and the alleged repression of Baloch civilians, the military’s efforts to expand influence over the current central government and curb provincial financial autonomy only adds to the sense of exploitation and injustice in Balochistan. The Pakistani government unveiled a new federal budget in June 2020, increasing military spending by nearly 12% (Dawn, 13 June 2020). This is just one example of the military’s pervasive influence over the current government (Al Jazeera, 1 July 2020; Foreign Policy, 8 July 2020). Several prominent positions within the government have been filled by retired and serving army officials, including the Prime Minister’s communications advisor. In May, opposition parties raised concerns over the government’s effort, aided by the military, to roll back constitutional reforms made in 2010 (Gandhara, 18 May 2010). These reforms restored parliamentary democracy, transferred power from the center to the provinces, and delegitimized military coups (Gandhara, 15 May 2020). The administration has now made calls to review these constitutional amendments, arguing that they limit the federal government’s authority to devise a national strategy to fight the coronavirus pandemic (Arab News, 30 April 2020). The federal government could use the pandemic as a pretext to assert more authority in the provinces, including in Balochistan.

Conclusion

Despite sporadic attacks, Balochistan’s insurgency was relatively dormant for the past three years, as internal divides among Baloch separatist groups and the success of the NAP weakened its operational capacity. The current increase in Baloch militant activity and recent success against security forces suggests a resurgence of Baloch militant groups as a result of reorganization and expanded capabilities fortified through new alliances. These alliances and capabilities, coupled with a renewed sense of exploitation by the central government and military forces, may also help the insurgency attract new recruits, further aiding the resurgence. Whether the Baloch separatist groups will be able to sustain their newfound alliances and capabilities, and transform them into larger political gains for Balochistan, remains to be seen.

Appendix: Main Baloch Separatist Groups

| Baloch Liberation Army (BLA) | The BLA is a Baloch separatist group currently led by Hyrbyair Marri (Gulf News, 3 July 2019). The BLA was founded in 2000, and targets security forces and civilians, demanding the separation of Balochistan from Pakistan (Stanford University, February 2019). |

| United Baloch Army (UBA) | UBA is a Baloch separatist group currently led by Mehran Marri, the brother of Hyrbyair Marri who leads BLA. The group was created as a result of a dispute between the brothers, leading to Mehran’s separation from BLA (Stratagem, 2017). |

| Baloch Liberation Front (BLF) | The BLF is a Baloch separatist group currently led by Allah Nazar Baloch. BLF was founded in Syria in 1964, and has historically been involved in Baloch insurgencies in Iran and Pakistan. BLF is currently battling the government of Pakistan for an independent Balochistan state (Stanford University, February 2019). |

| Baloch Republican Army (BRA) | The BRA is a Baloch separatist group founded in 2006 and currently led by Brahumdagh Bugti. The BRA is predominantly composed of members of the Bugti tribe, and targets security forces and civilians. They are opposed to central government control of provincial resources, and are against foreign investment in the region (Stanford University, February 2019). |

| Baloch Raaji Ajoi Sangar (BRAS) | The BRAS is an alliance between BRA, BLF, and BLA formed in 2018 (Terrorism Monitor, 20 September 2019). |

© 2020 Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). All rights reserved.