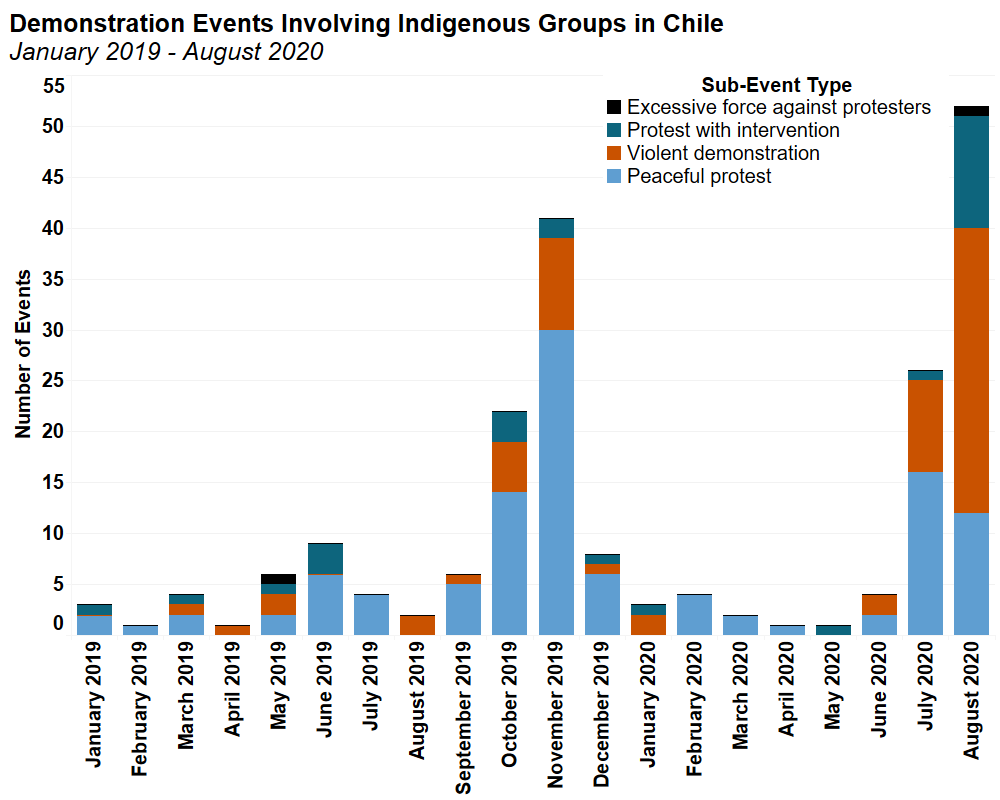

Tensions between indigenous communities and the Chilean government have simmered for decades over questions of land reform and discrimination, intermittently erupting in unrest and violence. The wave of nationwide demonstrations that began in October 2019 changed the political landscape and generated new opportunities for indigenous movements to push their demands forward. Despite an initial decrease in demonstration events during the first months of the coronavirus pandemic in 2020, there was a significant increase in demonstrations beginning in July and continuing into August. The increase comes as indigenous communities push for constitutional reforms ahead of a constitutional plebiscite scheduled for 25 October 2020. Meanwhile, organized political violence1Organized political violence events are inclusive of battles, explosions/remote violence and violence against civilians events in the ACLED dataset. by indigenous militias has also increased as they have seized the opportunity to attack rural areas while state forces focus their efforts on enforcing pandemic-related curfew and quarantine regulations in urban areas.

Demonstrations for Constitutional Reforms

Indigenous communities account for nearly 12% of Chile’s population. Of these, 79% identify as members of the Mapuche ethnic group, making it the largest indigenous community in the country (INE, June 2018). Despite their substantial numbers, the rights of indigenous people are not recognized by Chile’s constitution (Donoso & Palacios, 2018). Indigenous people continue to face racial discrimination and live mainly in poor, rural communities in the south of the country.

Encouraged by the agrarian reforms of President Salvador Allende at the beginning of 1970s, indigenous groups reclaimed their ancestral lands from private businesses and landowners. After the military coup on 11 September 1973, military troops under the regime of General Augusto Pinochet ousted indigenous communities from private farmlands (Andersen, 2010). Nevertheless, indigenous people continued to call for structural reforms and militia groups began arming themselves.

By 1992, a democratic government was elected, and infrastructure and energy industries began to develop projects in territories traditionally occupied by indigenous groups, increasing tensions between indigenous people and the state. During the 1990s, government representatives failed to approve a law recognizing indigenous communities and their autonomy. Many organizations advocating for the right to autonomy and land were formed during this period.

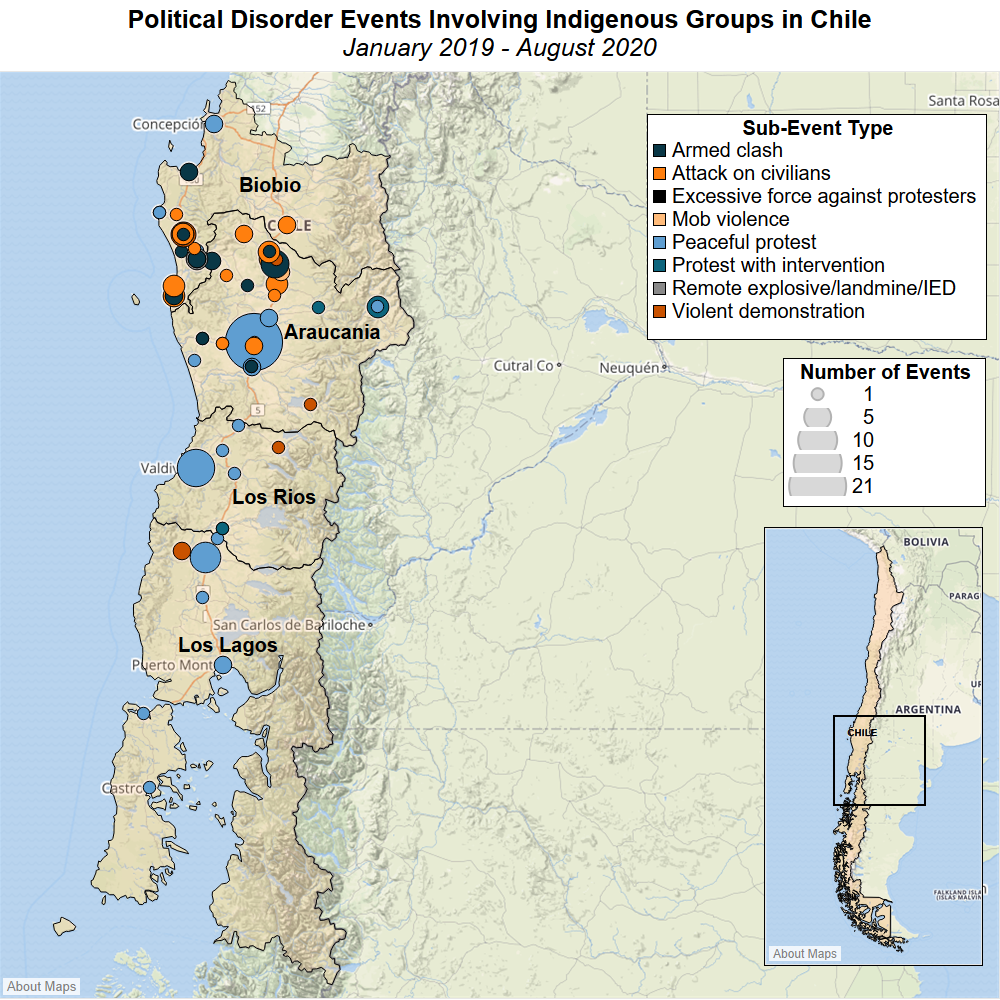

Today, tensions over stalled reforms manifest largely through demonstration events, as well as sporadic armed clashes between police forces and indigenous militia groups, particularly in the rural areas of the Biobío, Araucanía, Los Ríos, and Los Lagos regions (see map below).

Amid the ongoing pandemic, indigenous groups claim the government’s response to the crisis deliberately overlooks the needs of their communities (The Guardian, 10 July 2020; EFE, 31 May 2020). The rising number of coronavirus cases has forced communities to unilaterally institute measures to prevent the spread of the disease. The insistence of government officials on a centralized response has further undermined the relationship between the state and local indigenous groups. Moreover, human rights organizations have called for the protection of detained Mapuche individuals, as the coronavirus has spread in the country’s prisons. In a public statement, Amnesty International voiced its concern regarding the 27 Mapuche prisoners currently on hunger strike, among them the religious leader, Celestino Córdova (Amnesty International, 21 July 2020).

By July 2020, indigenous demonstrations increased significantly (see figure below) as Mapuche activists simultaneously occupied the town halls of several municipalities in the Araucanía and Biobío regions (Radio Universidad de Chile, 2 August 2020). The demonstrations followed unsuccessful negotiations with the government to allow Mapuche prisoners to stay under house arrest due to the health risks associated with COVID-19. A significant increase in violent demonstrations was reported in August after police evicted the Mapuche activists who were occupying the town halls. The evictions followed a public speech by the recently appointed Minister of Interior, Víctor Pérez, rejecting accusations that the detained Mapuche prisoners were political prisoners (Biobio Chile, 31 July 2020). Subsequently, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) sent a fact-finding mission to the country to gather information on the health of the Mapuche prisoners and to examine the actions of the police during the evictions of the demonstrators occupying the town halls (UN News, 15 August 2020).

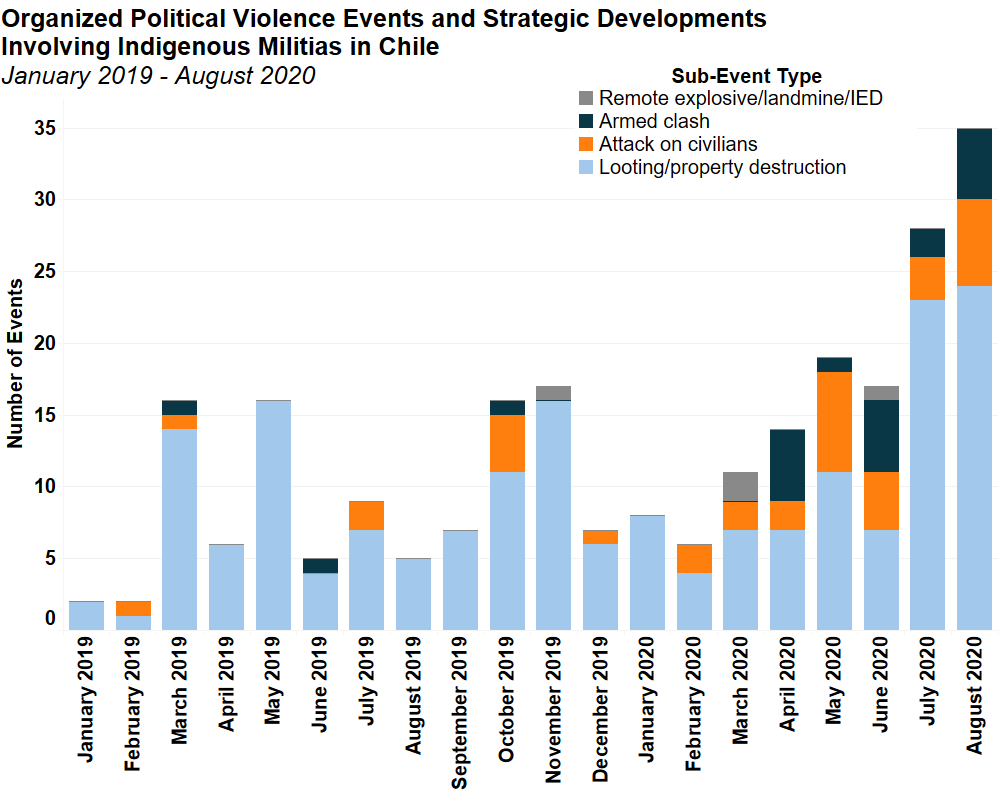

Increased Indigenous Militia Violence

While military and police forces have focused their efforts on enforcing curfew and quarantine regulations in the urban areas of the country during the coronavirus pandemic, indigenous militias have seized the opportunity to carry out operations across rural areas. ACLED records 47 organized political violence events involving indigenous militia groups from January to August 2020, an increase of 42 events compared to the same period in 2019. Furthermore, between March and August 2020 there has been an increase of attacks against civilians and armed clashes involving indigenous militia groups (see figure below).

Indigenous militias have also often carried out arson attacks and sabotage operations against logging and industrial agriculture companies, as well as private homes located in areas traditionally assumed to belong to indigenous communities. These events have at times led to civilian casualties.

Indigenous militias have also often carried out arson attacks and sabotage operations against logging and industrial agriculture companies, as well as private homes located in areas traditionally assumed to belong to indigenous communities. These events have at times led to civilian casualties.

The Mapuche group Coordination Arauco Malleco (CAM), and its armed wing, are especially active. The CAM has repeatedly released statements taking credit for arson attacks against logging companies and state targets, justifying the violence as a legitimate means to achieve their political goals (Infobae, 27 November 2017).The organization Weichan Auka Mapu (WAM), a splinter group of CAM with similar demands and similar tactics, has claimed responsibility for attacks against churches and other civilian targets (El Austral de Temuco, 3 September 2017). Activity by other militias — such as the Mapuche Lavkenche Resistance (RML) — has been reported, but, so far, few details about these organizations are known.

In fact, there is limited information about the number of indigenous militia groups in Chile. The groups operate in small units in the rural areas of the country; tracking militia members is a challenge for state forces. As the activity of indigenous militias has increased, the state has responded by deploying security forces to patrol sensitive areas in the Araucanía and Biobío regions, resulting in the arrests of Mapuche individuals suspected to be involved in attacks.

This response has been widely criticized by Mapuche communities, as such arrests have been mishandled in the past (El Desconcierto, 24 June 2020). In 2017, under the protection of the National Security Law passed during the military dictatorship, police officers arrested eight Mapuche leaders, accusing them of having links with the CAM and WAM indigenous militias. In January 2018, it was found that the police had manipulated evidence through the fraudulent interception of messages on cell phones to incriminate the detained Mapuche activists (Telesur TV, 3 April 2018). In another event, 24-year-old Camilo Catrillanca, a well-known student activist and grandson of a prominent Mapuche leader, was shot dead by police officers while riding on a tractor on a local road in the Araucanía region. The officers claimed he was suspected of being involved in a robbery and his death was the result of an armed clash. Video footage of the event later revealed that Catrillanca was unarmed (The Guardian, 29 November 2018). Both cases have contributed to Mapuche distrust of the state and explain the ongoing push by indigenous activists for the release of the detained Mapuche prisoners on hunger strike.

Conclusion

The demand of Mapuche and other indigenous communities for recognition of their rights and self-determination has created new challenges for a state that, until recently, was mostly confronted with the collateral effects of drug trafficking and political violence in neighboring nations. As the government continues to dismiss the demands of indigenous communities for comprehensive reforms to the constitution, increased political autonomy, and the redistribution of land, longstanding tensions risk boiling over into increased political disorder.

© 2020 Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). All rights reserved.