This is a joint brief published with the London School of Economics (LSE) Latin America and Caribbean Centre by Carolina Castro (University of the Andes), María del Pilar López Uribe (University of the Andes), Fernando Posada (UCL Americas), Bhavani Castro (ACLED), and Roudabeh Kishi (ACLED).

For a Spanish version, please click here.

The 2016 Peace Agreement signed between the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) marked a fundamental milestone in terms of guarantees for the life and conditions of the rural sector. The numbers of homicides and deaths associated with the armed conflict decreased significantly during the years of negotiation, and right after the signing of the agreement. However, the challenges in implementing subsequent commitments, as well as the presence of other armed actors, has evidenced new threats to the life of citizens, related to disputes over territory and resources, aggravated in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

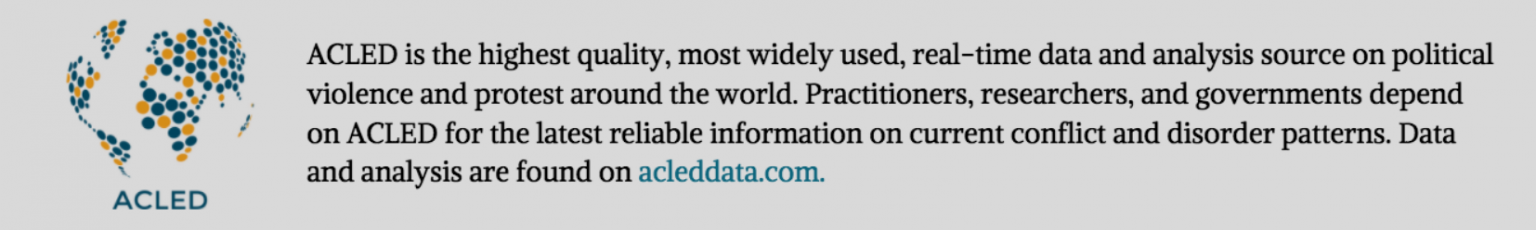

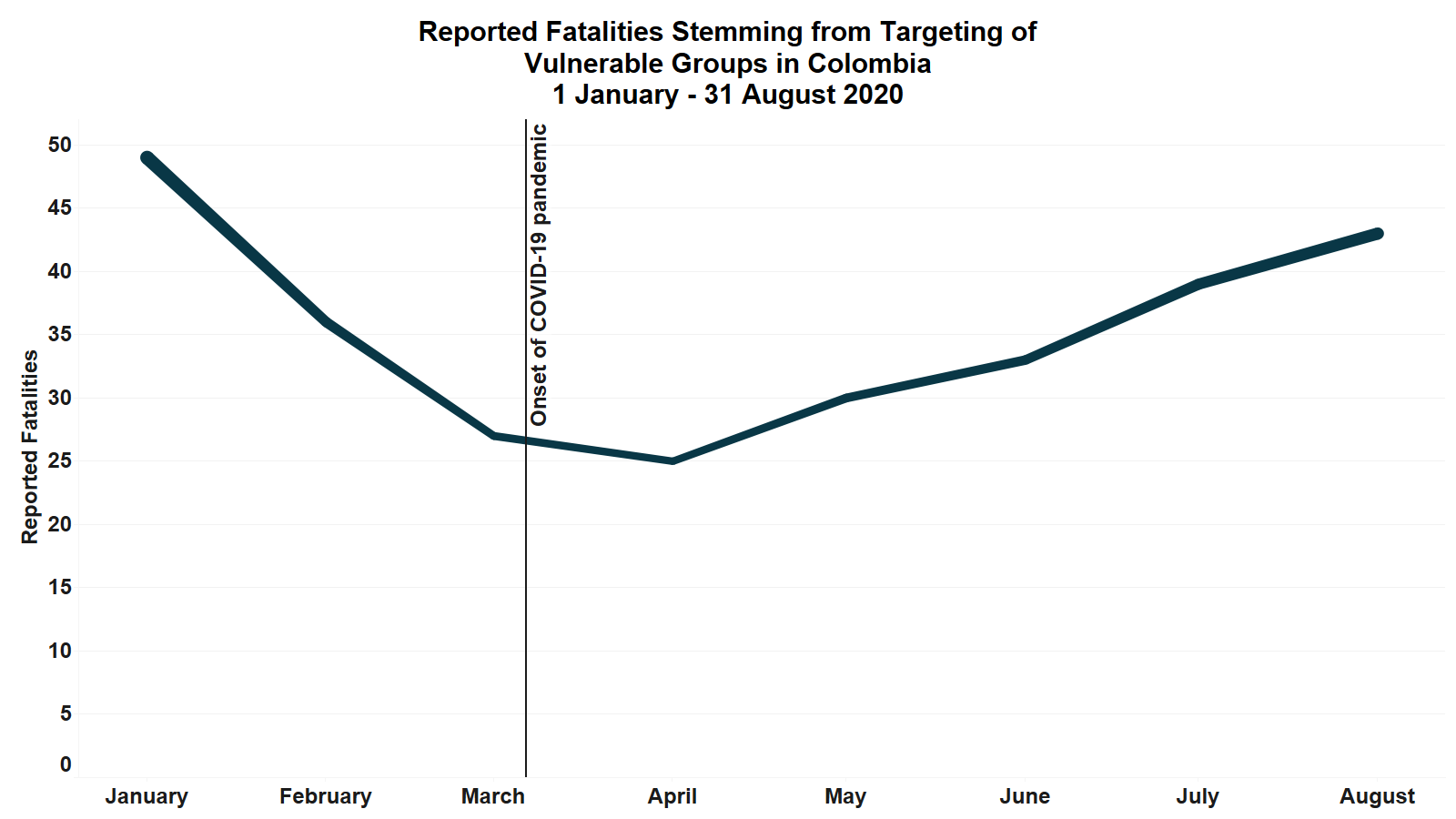

The killing of social leaders and members of vulnerable groups in Colombia has seen a dramatic rise thus far in 2020. At the beginning of the year, the number of killings was two times higher than the number of killings reported in the first months of 2019. The beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and strict quarantine measures reduced this trend, leading to a slight decrease in reported killings. However, once the health crisis settled, the deterioration of the security situation in rural areas has led to an increase in the death toll.

Although the exact numbers of killings vary depending on the source, the trends observed are similar: in recent months, there has been an alarming increase in the killings of social leaders and members of vulnerable groups, relative to pre-pandemic months (January-March 2020) as well as in comparison to the same period last year (April-August 2019).

A Stalled Peace Process and COVID-19

The failure to comply with the Havana Agreement has resulted in communities losing confidence in the government and in state institutions. At the same time, risk factors for leaders who had supported the process have increased. By committing to peace, leaders became the visible face of their communities. And as such, after the agreement, armed actors knew their profiles: where they were, which populations they represented, in which areas they had influence, and how protected they were — factors which facilitated the threats against their lives.

Since the coronavirus lockdown began, these risks have intensified. Several leaders were left alone inside their communities and homes, in many cases without protection or bodyguards. The confinement has facilitated intimidation by armed groups, especially as they know the locations of the leaders and that they are unprotected.

How to Track the Killings of Social Leaders and Members of Vulnerable Groups?

Data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) allow for the tracking of these trends. The killing of social leaders, given its very targeted — and hence not widespread — nature, rarely makes international news or mainstream media until reaching a tipping point. This makes it difficult for data projects relying on mainstream media alone to track such trends. ACLED prioritizes local media, and supplements these trends with information from NGOs and local community networks. Over 10% of ACLED coverage comes from these types of sources.

For example, in Colombia, this includes information from the Instituto de Estudios para el Desarrollo y la Paz (INDEPAZ), a Colombian NGO monitoring conflict in Colombia, as well as information from Front Line Defenders, an ACLED partner who aims to protect human rights defenders around the world through local networks. These types of non-media sources help to provide details around over a quarter of violence against civilians in Colombia.

The events analyzed in this piece refer to social leaders and members of vulnerable communities – including farmers, indigenous people, and Afro-descendants. This category also includes other groups which are frequently targeted, such as members and former members of the government, political parties, journalists, women, teachers, students, and LGBT people. In the context of the peace process, former Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and National Liberation Army (ELN) combatants who decided to reintegrate into society are also frequent targets of attacks perpetrated by armed groups.

Changes in the Killings of Social Leaders During the Pandemic

ACLED data indicate that since April 2020, there had been an average of over 6 killings of social leaders and members of vulnerable groups reported each week. This increased to over 10 killings a week, on average, by the end of August 2020, when the nationwide lockdown was lifted (see graph below).

Three Hypotheses on the Killings of Social Leaders and Members of Vulnerable Groups

The first hypothesis regarding the increase in the killing of social leaders and members of vulnerable groups stems from the direct link between the end of the armed conflict and the dispute over territories considered abandoned by the FARC. The attacks have been linked to the implementation of the peace agreement in 2016 and the dispute and strengthening of different armed groups in conflict areas.

One of the consequences of this shift in power has been the emergence of new armed groups, which often recruit former FARC combatants; these groups have emerged in disputed territories and aim the control drug trafficking and illegal mining activities. More than 60 killings have been attributed to FARC dissident groups, and more than 50 to former paramilitary groups or international cartels.

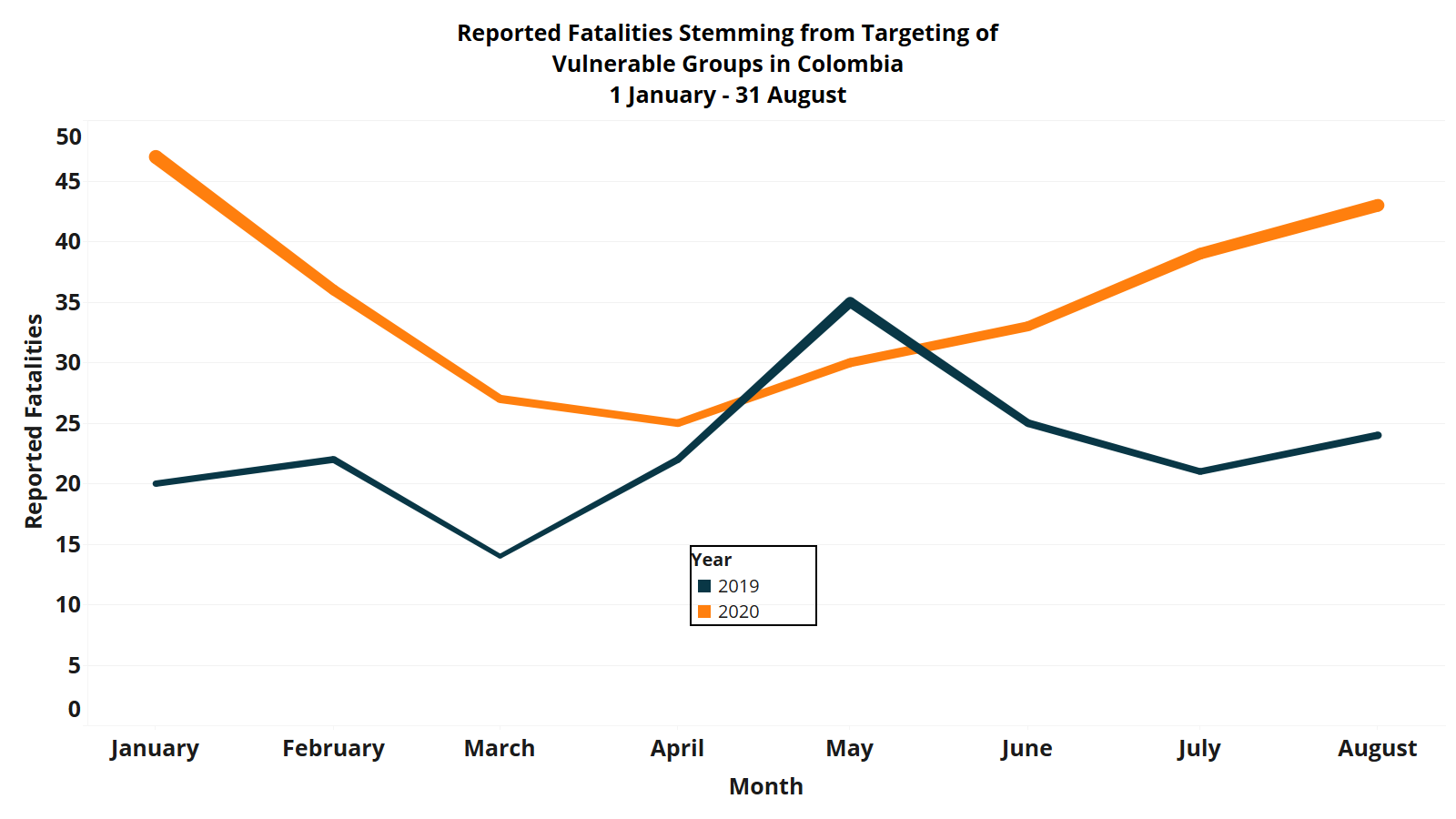

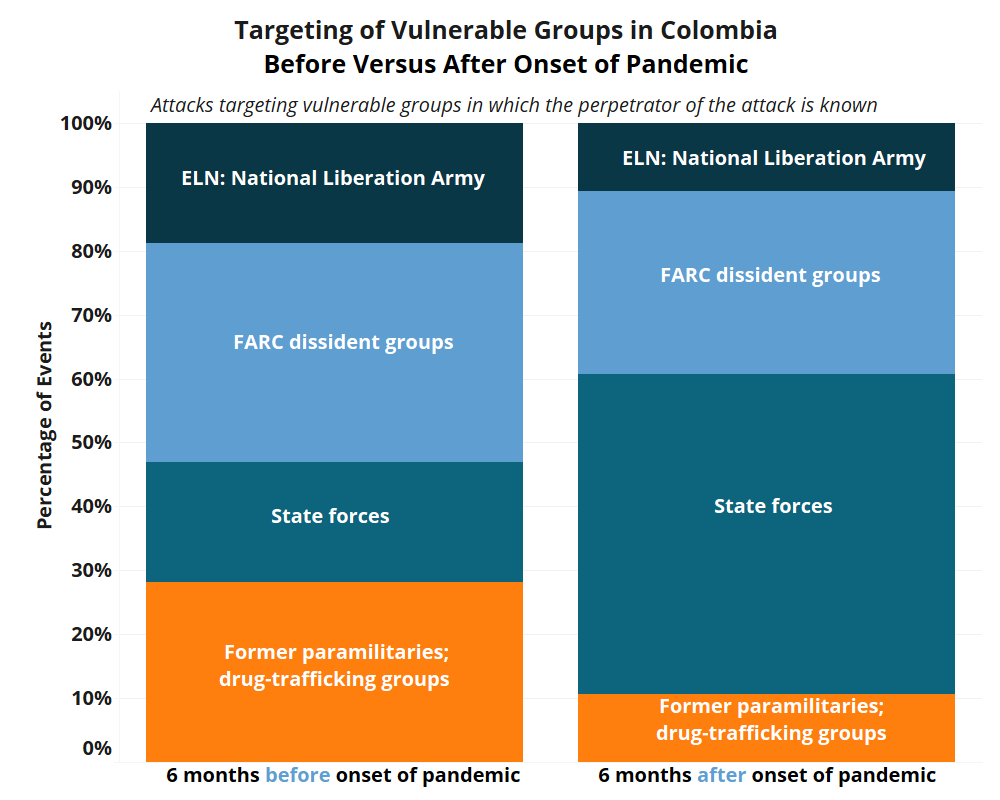

Of events in which vulnerable groups are targeted — in which the perpetrator of the attack is known — the participation of members of state armed forces is increasingly observed; these cases went from 18% of attacks against vulnerable groups in which the perpetrator of the attack is know before the onset of the pandemic to 50% of such events afterward (in teal in graph below). Most of these events are directly linked to operations to eradicate coca crops carried out by the state armed forces.

In the six months since the onset of the pandemic, nearly one-third (28%) of attacks on vulnerable groups in which the perpetrator of the attacks is known are perpetrated by FARC dissident groups (in light blue in graph below). This trend mirrors the months prior to the onset of the pandemic as well.

Finally, the third hypothesis regarding the increase in the killing of social leaders and members of vulnerable groups stems from land disputes and environmental issues, which is partially related to the other two hypotheses above. The current process of land restitution in disputed territories puts farmers that are returning, after having been displaced by conflict, at risk. In 2020, nine of the victims killed took part in the land restitution process. Environmental leaders who fight against controversial development projects and the exploitation of natural resources are most vulnerable amidst the rising tensions from armed groups vying for territorial control. According to a recent report from the NGO Global Witness, “Defending Tomorrow”, Colombia ranks first in the world in the killing of environmental leaders, with 64 reported deaths in 2019.

Alternative Explanations: COVID-19, the Economic Crisis, and Territorial Control

In recent months, the public sphere has been focusing their efforts on addressing the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. The health pandemic has required a high concentration of time, debate, and resources from the state and from human rights NGOs, including in aspects such as control of mobility, health, and the economic effects of quarantine. In the midst of a crisis that has disrupted the ways of life and the priorities of state agents and NGOs, the country’s structural problems, such as systematic violence in rural areas, have been neglected and have been pushed to the background. Most public offices have been closed, which blocked the access of citizens to channels of attention and protection. Similarly, the activity of human rights NGOs and their field work have been severely limited by mobility restrictions implemented throughout the country. Additionally, the effects of the pandemic on the most vulnerable populations have not been minor and have required many NGOs to refocus their attention and support for communities around basic issues, such as food security and health.

For example, the department of Meta has a higher than average number of areas of reintegration, with three Territorial Spaces for Reintegration and Incorporation (ETCR) located in this department. In the first six months following the beginning of the pandemic, five times as many events were reported in Meta in which vulnerable groups were targeted relative to the six months prior to the onset of the pandemic. Many of these incidents involve the killing of former FARC combatants who were living in reintegration camps. Analysts have previously raised concerns about the government’s ability to assure the safety of former combatants living in the camps, especially as the temporary arrangement of the camps have already expired and the government has not yet released plans to make them into permanent facilities or villages (Insight Crime, 1 November 2019).

Another aspect to consider is the lack of attention and visibility of the situation of social leaders in public discourse. Despite the fact that the situation of vulnerable groups in the country has worsened in 2020, attention to the issue has decreased significantly in the public sphere. News channels have been focusing on reporting around the COVID-19 pandemic and its impacts. Rural security issues, protection of social leaders, and the vulnerability of human rights have been temporarily moved out of public discourse as the pandemic’s effects on health issues and the economy have also significantly affected vulnerable populations. In this context, communities living in remote areas are increasingly neglected from the national discussion, which further isolates them and increases their degree of vulnerability.

Less information, research, and attention on the subject may also be responsible for armed actors targeting vulnerable groups going unpunished — both socially and legally. An indirect strategy to highlight the decline in media attention is to analyze search trends on Google. These reflect a notable increase in searches related to the effects of the health crisis (on topics such as the economy and unemployment) and a low search trend for human rights-related topics in the post-conflict context.

As such, protection and guarantees have decreased since the onset of the health pandemic and quarantine restrictions in Colombia with the focus of the public shifted to the health crisis.

A second alternative hypothesis regarding the increase in the killings of vulnerable groups refers to the relationship between the pandemic and new opportunities for territorial control by non-state armed groups. The coronavirus pandemic has been used as an excuse by armed groups to implement strategies of coercion and to exert control in disputed territories. Armed groups enforced curfew and lockdown measures in at least 11 departments of Colombia (Insight Crime, 3 September 2020), including in longstanding conflict-ridden Antioquia, Cauca, and Nariño departments. Dissident groups of the former FARC threatened to kill quarantine breakers in Cauca, while in Nariño measures were established by several groups, including dissident FARC groups, the ELN, and the Gulf Clan.

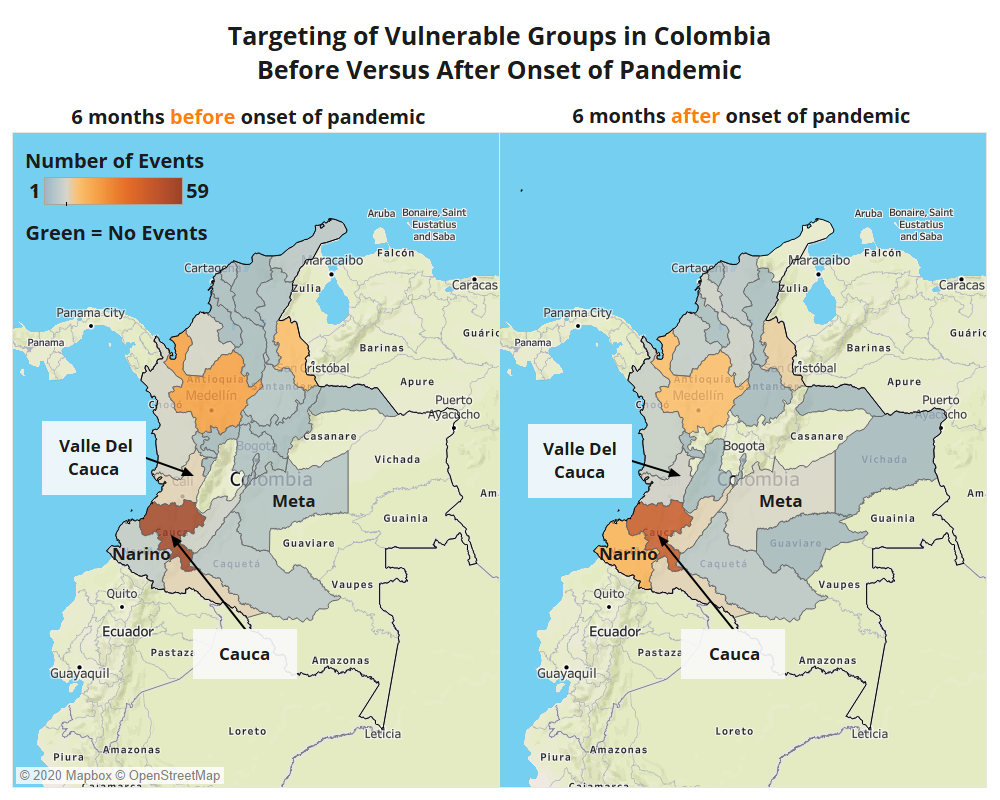

Structural Factors in the Southwest of Colombia

In addition to pandemic-related explanations, structural aspects also contribute to the intensification of violence reported in the southwest of the country. Nariño is one of the main territories where coca is produced, due to its rural conditions and its access to the Pacific Coast and Ecuador, where most of the production can be distributed to the United States and other international markets (InSight Crime, 30 October 2019). According to local authorities, the killings taking place in Nariño can be attributed both to an increase in the local production of coca and to the escalated territorial dispute between the ELN and other armed groups (Caracol, 18 August 2020), which take advantage of the lack of state presence in the area. The ELN used to control several territories of the department, but with the arrival of the Gulf Clan and different FARC dissident groups in strategic areas, its dominance has been challenged. This increase in civilian targeting in Nariño can be seen in the maps below; the map on the left depicts the six months prior to the onset of the pandemic, while the map on the right depicts the six months following, in which it is clear that the targeting of social leaders in Nariño has increased threefold.

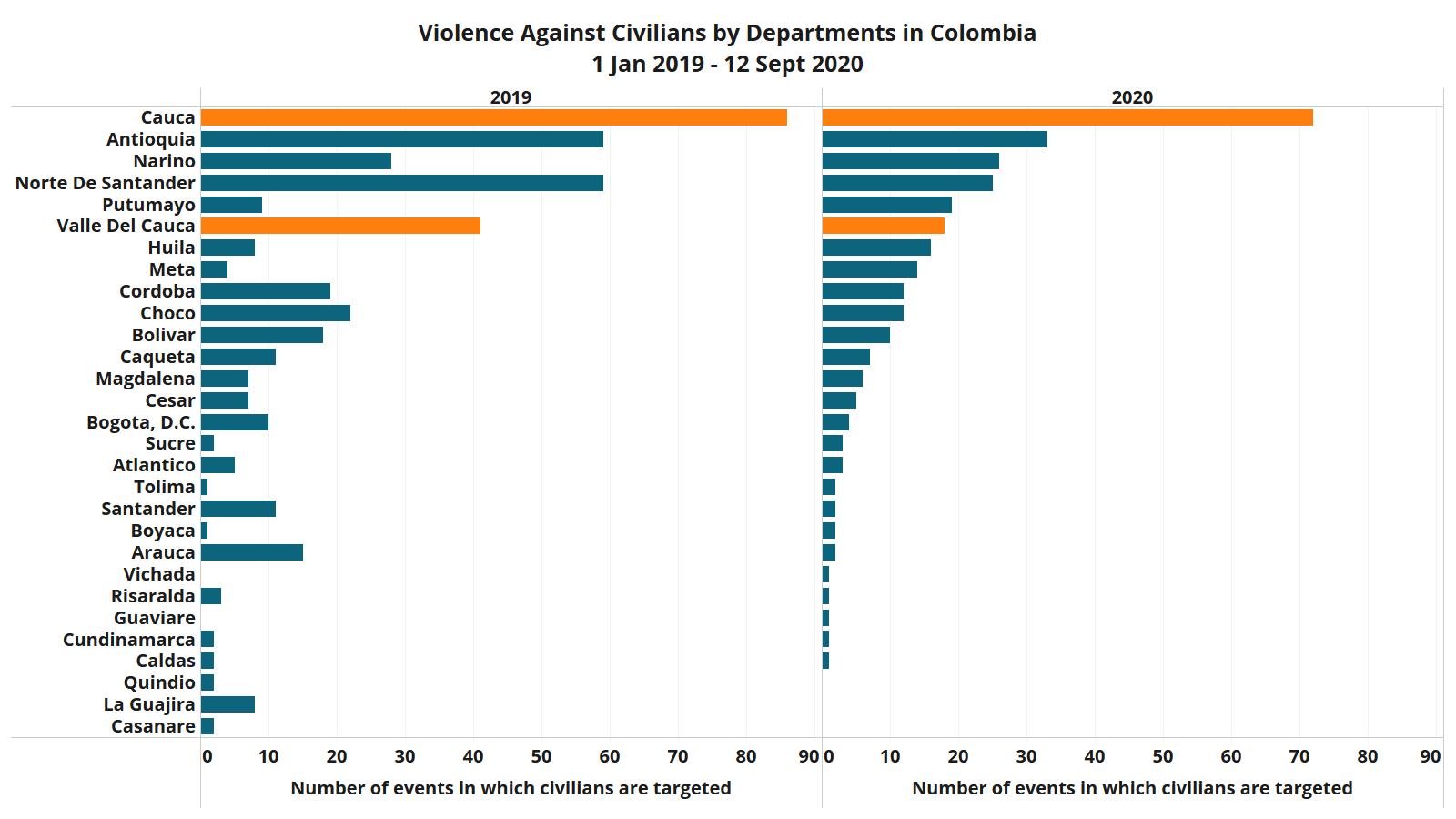

The departments of Cauca and Valle del Cauca (highlighted in orange in the graph below) have been hotpots of Colombian armed conflict since the existence of the Cali Cartel, as the region is known for the production of coca plants and access to the Pacific Coast. In the northern area of Cauca department, the strong presence of indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities who oppose the use of their lands being used for coca crop production has made them increasingly vulnerable to attacks perpetrated by different armed groups present in the region.

Where is the State?

The state should not only investigate these killings, but it should actively engage in measures to guarantee the protection of rights of social leaders and vulnerable groups. The killings are part of a more aggressive phenomenon, since it takes place in territories where structural disputes have historically been taking place. Land and resources disputes include the production of illicit crops, drug trafficking, and illegal mining activities. These disputes should be addressed in a comprehensive, articulated manner, focusing on the strongest actors in the chains of illegal economies. This could contribute to reducing the vulnerability of small farmers, indigenous people, and communities of Afro-descent who lead the defense of their territories at the cost of their lives.

© 2020 Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). All rights reserved.