Despite a nationwide lockdown imposed on 24 March to curb the spread of the coronavirus, India has continued to record a steady increase in COVID-19 cases. On 16 September, India reached a record five million coronavirus cases, becoming the second country in the world — after the United States — to report such figures (Times of India, 16 September 2020). Amid the pandemic, India has continued to face conflicts in multiple regions. This includes the geopolitically sensitive northeast region. The region faces a number of issues, ranging from ethnic violence to separatist and secessionist insurgencies, as well as problems arising from identity politics, cross-border immigration, and inter-state boundary disputes. The onset of the pandemic has impacted political disorder patterns across the region, increasing the risk of instability and unrest.

CAA Demonstrations Decline During Pandemic Lockdown

India’s northeast region includes eight states: Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Tripura, Manipur, Mizoram, Meghalaya, Nagaland, and Sikkim. The region is ethnically diverse and considered to be one of the most volatile regions in South Asia. The region spearheaded the demonstration movement against the controversial Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) throughout 2019, with Assam being the epicenter of the demonstrations.

The CAA came into effect on 10 January 2020. It grants citizenship rights to undocumented immigrants (The Hindu, 10 January 2020), specifically Hindus, Sikhs, Jains, Buddhists, Christians, and Parsis from neighboring Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Bangladesh fleeing religious persecution (Hindustan Times, 2 August 2020). Some critics argue the CAA is exclusionary toward the Muslim population, as it denies the same citizenship rights to Muslim migrants. In the northeast, tribal groups contend that it will encourage the migration and settlement of non-indigenous populations — particularly Hindus from neighboring Bangladesh — in the northeast region. The region has been a focal point for immigration from Bangladesh. Issues regarding immigration policy have been a longstanding source of conflict between indigenous and immigrant populations (for more on the CAA, see this ACLED infographic). There is concern that increased migration would considerably alter the demographics and cultural identity of the region, and strain resources (Economic Times, 17 December 2019).

When the coronavirus began to spread in early 2020, it had a multifaceted impact on political violence and demonstration activity across India, which was already in the midst of a wave of political disorder after the passage of the CAA (for more, see this ACLED CDT spotlight).

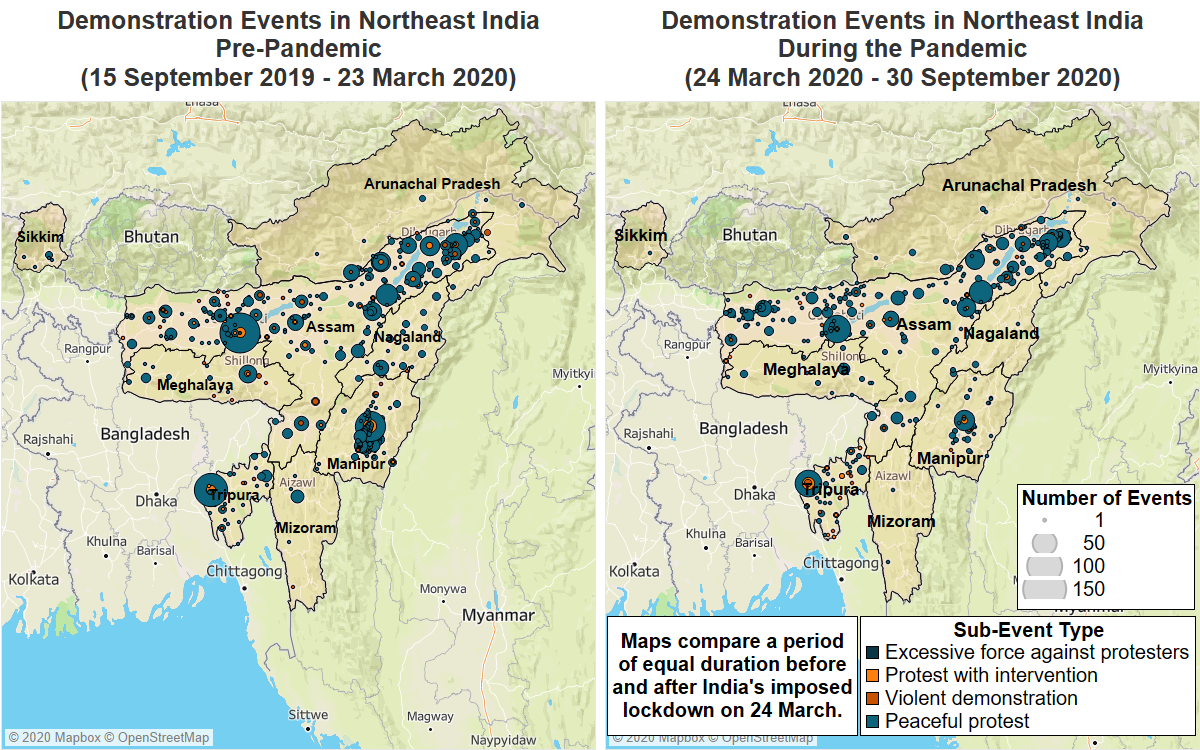

ACLED records a 40% decrease in demonstration activity in the northeast between 24 March — when India imposed the nationwide lockdown — and 30 September when compared to a similar time period pre-pandemic. After the imposition of the lockdown, close to 1,060 demonstration events were reported compared to more than 1,760 demonstration events in the period prior to the imposition of the lockdown (see figure below).

The decline in demonstrations can primarily be attributed to fear of infection, in addition to government restrictions related to the lockdown. Moreover, many prominent groups leading demonstration campaigns voluntarily decided to pause their activity (Times of India, 18 March 2020). For instance, in Assam, groups such as the All Assam Students’ Union (AASU) and Asom Jatiyatabadi Yuva Chatra Parishad (AJYCP) suspended their anti-CAA protests in the state (Time 8, 16 March 2020). AASU and AJYCP are student groups with the stated goal of safeguarding the interests of Assam’s indigenous population. They led the Assam movement which was directed against the resettlement of Bangladeshi nationals in the state from 1979 to 1985. The native Assamese opposed such migration, fearing the erosion of their cultural identity (Northeast Today, 23 December 2019). Recently, the two student bodies have jointly formed a new political party — Assam Jatiya Parishad (AJP) — in order to ‘secure the future of Assam and Assamese people’ (Hindustan Times, 14 September 2020). Before the imposition of COVID-19 lockdown restrictions, both groups had been spearheading the anti-CAA movement in Assam (The Hindu, 19 August 2020).

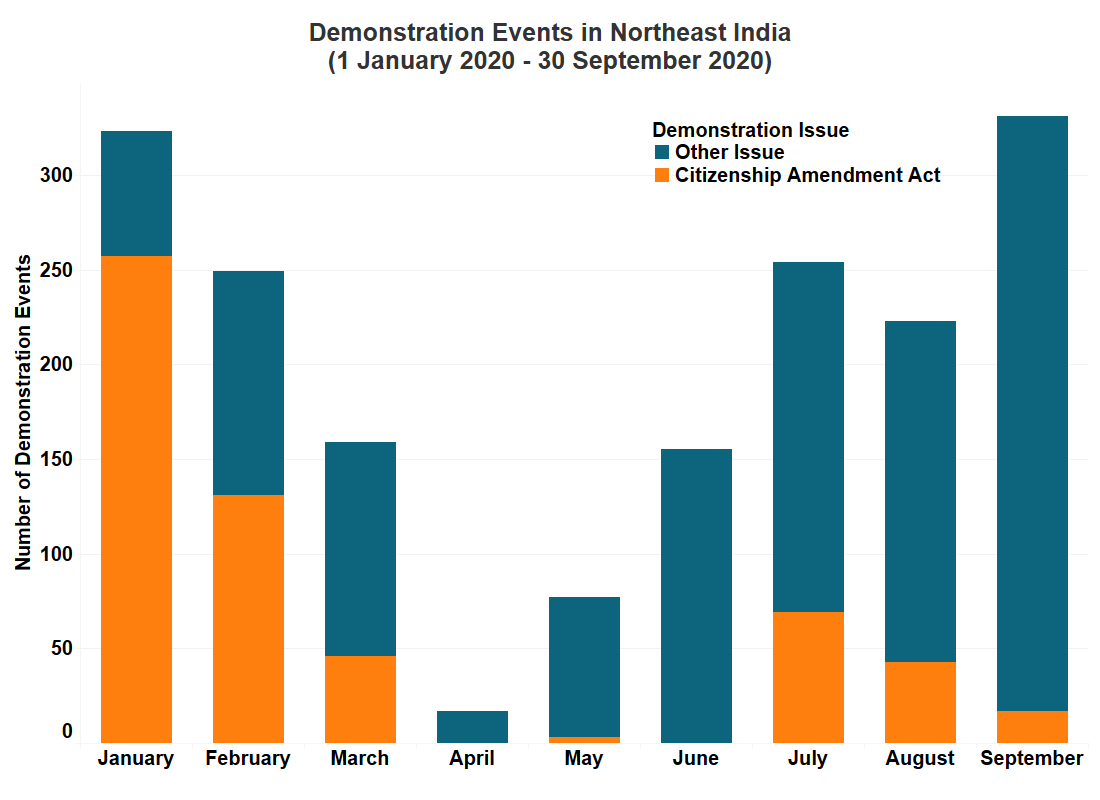

Demonstrations Reignite

While demonstration events sharply declined following the government’s imposition of the lockdown, an increase was reported from mid-June onwards. Of the almost 1,060 demonstrations recorded after the lockdown, over 900 demonstration events were recorded between 15 June and 30 September (see figure below). Some of these demonstrations were related to issues other than the CAA as well, such as the management of the coronavirus crisis by the respective northeastern state governments. Demonstrations were staged over a range of demands, including calls for financial assistance, an increased supply of rations, and better healthcare infrastructure to fight the pandemic. Of the 1,060 demonstration events recorded in the northeast between 24 March and 30 September, around 320 were related to the coronavirus. Furthermore, with the easing of lockdown restrictions, the groups that had voluntarily paused their demonstration campaigns resumed activity in July, adhering to social distancing and mask protocols. From July through September, ACLED records over 130 demonstration events related to the CAA in Assam.

Increasing Violence Against Civilians in the Northeast

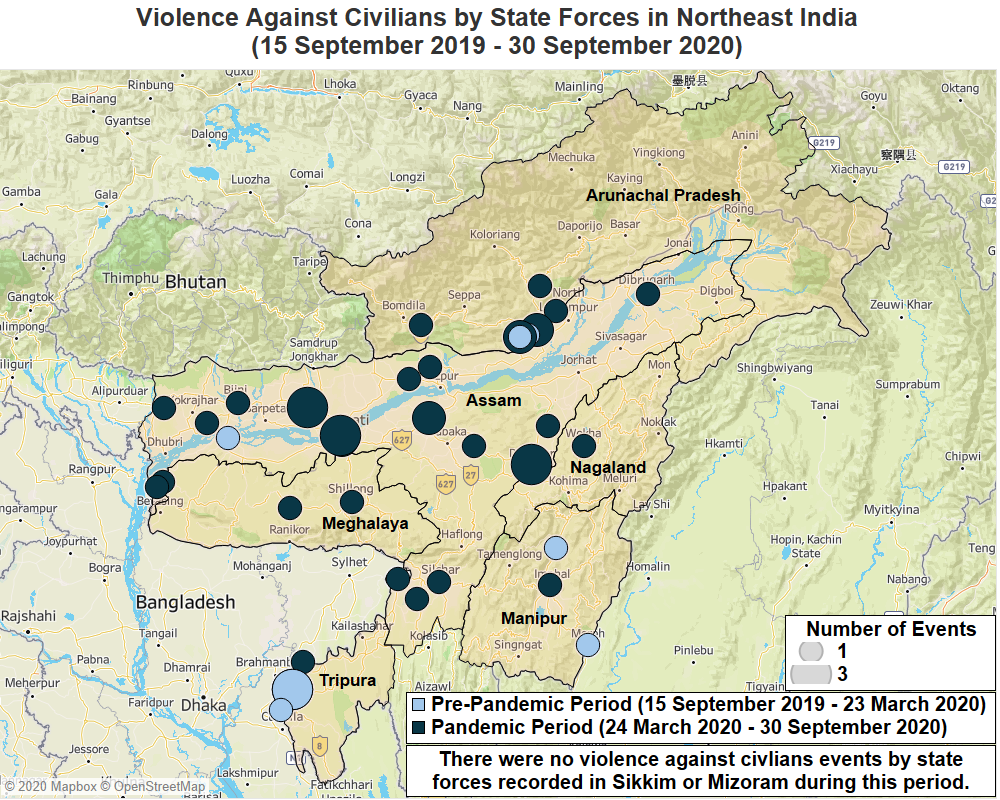

The pandemic also triggered state repression, with an increase in attacks on civilians by state forces (see figure below). The majority of these attacks were cases of violent enforcement of lockdown restrictions by state authorities. Between 24 March and 30 September, ACLED records 41 attacks against civilians by law enforcement agencies in the region. Only nine such events were recorded during the period prior to the pandemic. Additionally, strict lockdown measures further added to the political tension in the region, in many cases leading to clashes between demonstrators and police. The state was also accused of misusing lockdown measures to carry out unpopular activities despite public opposition. For instance, the AASU alleged that the state government imposed the lockdown and night curfew to transport construction materials meant for a hydro-power project, which the group had been protesting (Time 8, 8 July 2020).

Insurgents Under Lockdown

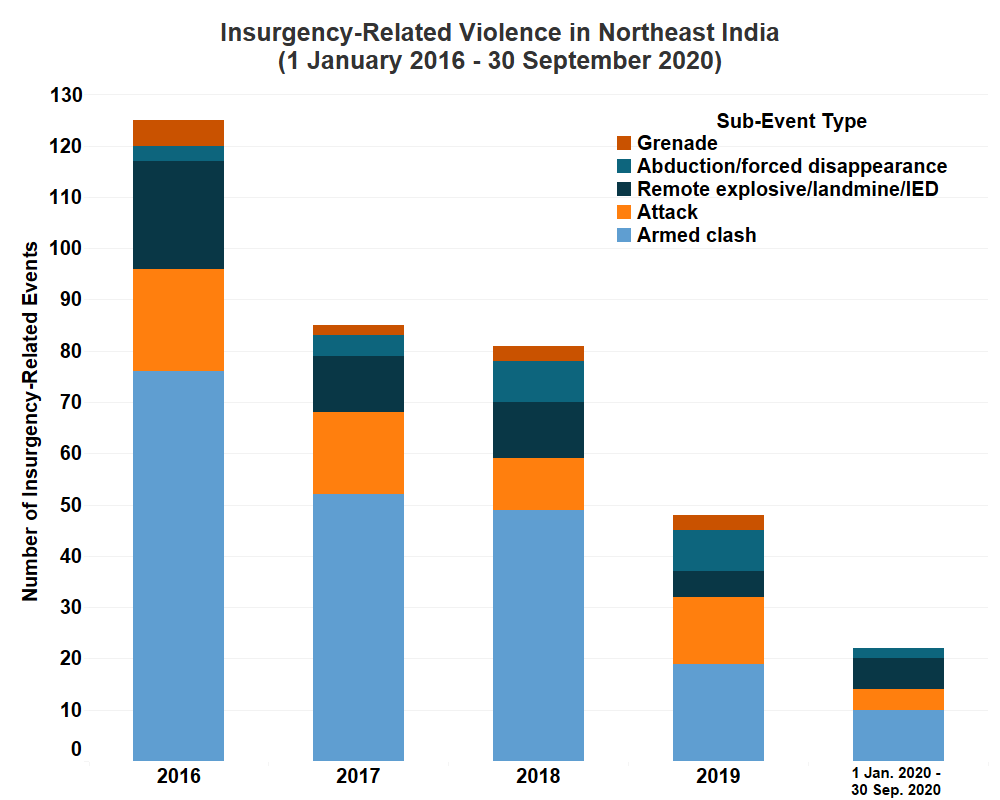

Since 2016, ACLED records a gradual decline in insurgency-related violence in the northeast region (see figure below). Prominent armed groups in the region — such as the National Socialist Council of Nagaland-Isak Muivah (NSCN-IM), United Liberation Front of Asom (ULFA), and National Democratic Front of Bodoland (NDFB) — are in peace talks with the Indian government (Government of India, 2019). Despite the decline in violence, many armed insurgent groups are still active in the region. After the imposition of the nationwide lockdown, state forces conducted raids, arrests, and weapons seizures targeting these groups (Deccan Herald, 23 April 2020; The Telegraph, 8 May 2020; Sangai Express, 15 June 2020). Insurgent groups that have relied upon local support for food, medicine, and other supplies have faced disruptions to their supply chain amid the lockdown (The Economic Times, 28 June 2020). This has resulted in the surrender and desertion of armed cadres, as well as a sharp decline in extortion activities (The Week, 24 April 2020; News18, 15 June 2020).

At the same time, insurgent groups have been active in other areas, issuing statements about the pandemic, attempting to discredit the government, and claiming to speak for the general public. Groups such as NSCN-IM in Nagaland undermined the state government’s response to the COVID-19 crisis by releasing a statement criticizing its handling of coronavirus cases, as well as the slow construction of a local hospital (Economic Times, 15 April 2020). The group also reduced the ‘tax rate’ of its extortion activities during the pandemic (The Hindu, 5 July 2020). In Manipur, the United National Liberation Front (UNLF) appealed to private banks and money lenders for debt relief for vegetable vendors and traders during the pandemic (E-Pao, 5 April 2020). Moreover, joblessness caused by the pandemic has pushed young people in the region to join the militant ranks. Unemployed youth in the region are reportedly joining banned rebel groups such as the United Liberation Front of Asom-Independent (ULFA-I), among others (The Sentinel, 21 September 2020).

Conclusion

As the pandemic continues to spread across India, tension is mounting over the government’s management of the crisis, as well as its response to the varied demands of different groups. Increased state repression in the northeast — coupled with public discontent surrounding the management of the pandemic — could lead to another wave of political unrest going forward. The resumption of demonstrations against the CAA in Assam is only likely to add to the political disorder in the region. Furthermore, while an increased security presence during the pandemic lockdown has restricted the operations of armed insurgent groups in the region, these groups remain active, exploiting the coronavirus crisis to undermine the government. Rising unemployment in the region is pushing frustrated youth towards joining insurgent groups, and there is continued concern for peace and stability in the region.