Since its original introduction as a small-scale academic project in 2010 covering political violence in Africa (Raleigh et. al, 2010), the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) has evolved into an independent NGO with a global team of researchers collecting real-time data on political violence and demonstrations across the world. By mid-2020, nearly one million events were collected in the ACLED dataset for public use, complemented by a range of analytical reports and methodological advancements. Over the past 10 years, a number of significant changes have enhanced the flexibility, timeliness, and reliability of ACLED data. The changes adopted have advanced the project’s scope, deepened its engagement with researchers, and expanded its sources and quality of information. This special data feature reviews these changes and explains why ACLED has evolved in a distinct way compared to other conflict data projects. As a result of this evolution, the ACLED dataset has come closer to comprehensively and accurately representing the ground reality of global disorder than ever before, making it a key source for academics as well as policymakers, practitioners, and journalists around the world.

New Developments in ACLED Coverage

In 2020, ACLED is nearly global in its coverage. ACLED’s geographic expansions have required extensive reflection on how to compare conflicts occurring in different spaces and times; what is ‘political’ violence; and how sourcing and reporting can emphasize or obscure local patterns. These questions underscore an underappreciated fact within conflict studies: that all countries experience some forms of disorder. The modality of that disorder is strongly shaped by the specific vulnerabilities, political fault lines, and priorities of each society. In this article, we review the main changes in ACLED over the past 10 years, concentrating on the breadth and depth of content, sourcing, and methodological advancement.

First and foremost, ACLED expanded where and how it collects data on disorder, which combines political violence, conflict, and demonstrations. ACLED covers disorder wherever and whenever it occurs, rather than relying on the presence and intensity of specific forms of conflict and unrest to spur coverage. Conflict scholars require data where inclusion criteria have not biased the potential research outcomes. Countries that are not typically included in conflict datasets – such as the United States, Ireland, or Botswana – have protests, riots, or acts of repression by state security services. Our most advanced theories of conflict suggest that waning institutional trust and strength, income inequality, and demographics are sources of disorder and causes of political violence (Goldstone, 2001). Given that these features are now commonplace in higher-income states, tracing what may be early signs of instability is in the interest of the research community.

Further, disorder does not present as the same in every space, and by taking an expansive view of its modalities, researchers can use ACLED to accurately account for its occurrence and patterns. Spaces where political violence is high but dismissed as ‘criminal’ or difficult to categorize – such as in Mexico and Brazil – are given equal coverage to more ‘traditional’ conflict spaces, like Afghanistan or the Democratic Republic of Congo. Given existing and developing patterns of instability across the world, it is critical for researchers to consider the modality of unrest in high-income states; the differences in communal violence across identity groups; and the presence and range of armed, organized groups in ‘democratic’ states.

Second, ACLED is a ‘living dataset.’ Data are published on a weekly release schedule; this timing is designed to harness the most accurate and available information, and allows for near-real-time monitoring by users. It is also the basis for a robust and reliable early warning system. Further, ACLED is researcher-led, and prior to publication, data go through multiple rounds of review to account for inter-coder, intra-coder, and inter-code reliability that together allow for cross-context comparability. This regular oversight ensures the accuracy of events, and the avoidance of false positives and duplicates. Oversight continues after data are published: as more information comes to light, corrections and updates are uploaded to the dataset.1Event IDs for updated events remain the same as the original Event ID upon first publication; this allows users to update their information regularly with ease. Each week, approximately 10% of submitted events are updates to existing events. Further, targeted supplementation of key periods or through access to new sources of information means that coverage is always being strengthened.2For more information, see ACLED’s sourcing strategy document (ACLED, 2020a).

Third, and finally, ACLED enhanced event data methodologies for manual, researcher-led data collection. ACLED’s innovations here are to first emphasize that a standard ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to data collection and event coding is not a suitable or adequate response to the variability of modern disorder. Each state and its disorder risks are regularly reviewed by country experts and ACLED team members to ensure that data accurately reflect the most reliable information available. ACLED practices also prioritize data collection by rigorous, human researchers, as opposed to relying mainly or dominantly on automation. This ensures reliable and consistent data collection, and allows ACLED to harness information from a range of languages and sources.3Automated data collection procedures allow for numerous duplicate events as machines have difficulty distinguishing them; false inclusion because of false positives; limited oversight and limited capture, especially given that most are not able to scrape the internet for reports in much more than English alone. For more information, see Raleigh and Kishi (2019).

Further, open, continual, and transparent reviews and discussions of collection processes are features of all ACLED work, and this benefits both data developers and user communities. Users whose research is affected by coding decisions should be informed about how these choices are made, and how they will impact analysis. To fulfill these principles, in addition to codebooks, training, and explanatory materials, ACLED provides open access to methodology documents on a range of significant and specific issues. Examples include obstacles around coverage in Yemen, coding rules for various factions of Boko Haram, and how political violence targeting women data are collected, amongst many others. This methodological transparency ensures that coding remains standardized across countries, conflicts, and researchers. In addition to this documentation, the ACLED team remains accessible, with questions from users regularly received and addressed. These reviews and developments are necessary as even similar conflicts in different regions can be fundamentally distinct, and ongoing methodological decisions are made, implemented, and publicized to inform users. Offering a depository of information from which to make informed choices about event data forms and comparisons is a necessary feature of modern projects.

Content Advancement

ACLED captures disorder, defined as a catchment of both political violence and demonstration events. ACLED’s inclusion criteria for a political violence event is that an episode must involve at least one violent group with a political objective. ‘Political violence’ is defined as the use of force by a group with political motivations or objectives, which can include replacing an agent or system of government; the protection, harassment, or repression of identity groups, the general population, and political groups/organizations; the destruction of safe, secure, public spaces; elite competition; contests to wield authority over an area or community; mob violence; etc. ACLED casts a wide net to capture demonstrations as well, allowing any reported violent riot or peaceful protest of more than three people to be included, regardless of the reported cause of the action. Demonstrations are not considered to be ‘political violence,’ yet are a political act. These definitions are important to clarify as an act of political violence or a demonstration is the sole basis for inclusion within the ACLED dataset. Specific non-violent events are also included as ‘strategic developments,’ which are useful to capture contextually important events and developments which may contribute to a state’s political history and/or may trigger future political violence and/or demonstrations.4The ‘strategic development’ event type within the ACLED dataset is unique from other event types in that it captures significant developments beyond both physical violence directed at individuals or armed groups as well as demonstrations involving the physical congregation of individuals. Because what types of events may be significant varies by context as well as over time, these events are, by definition, not systematically coded. One action may be significant in one country at a specific time yet a similar action in a different country or even in the same country during a different time period might not have the same significance. ‘Strategic development’ events should not be assumed to be cross-context and -time comparable, unlike other ACLED event types. Rather, ‘strategic development’ events ought to be used as a means to better contextualize analysis. When used correctly, these events can be a useful tool in better understanding the landscape of disorder within a certain context. They are a way to ‘annotate a graph’: to make better sense of trends seen in the data.

ACLED’s broad catchment reflects the following tenets: modern disorder forms are best categorized by where they fall on a spectrum of armed, active organization. At one end, a state or international military body with an armed, hierarchical order can engage with all other conflict agents, be present across a territory, and is expected to be perpetually active. In turn, their event forms, intensity, and frequency is extensive. On the other end, there are unarmed protesters engaging in intermittent, highly specific and local demonstrations often with little organization, funding, and capabilities. Between these two extremes are rebel organizations which seek to address national-level power disparities; militias who are ‘hired’ and whose objectives are closely tied to a political patron; community armed groups who provide specific security services on a club good basis; cartels who require territorial and population control to engage in an extensive economic racket; violent mobs who respond to community threats with targeted violence before disbanding, largely emerging in areas with poor police presence and trust; and rioters who emerge to quickly create disorder before reconstituting or fading quickly. The underlying theme to these groups and forms of disorder is that they are all organized to varying degrees in a defined time and space to pursue political objectives, and many arm themselves to do so.

This spectrum of disorder is populated by incidents which have been categorized as event types and sub-event types. As ACLED has evolved since version 1 of the dataset, event types have been disaggregated and extended to include demonstrations and spontaneous mob violence, remote violence tactics, and political violence with a gendered target, to note a few examples. ACLED’s definitions and coding structure allow for extensive aggregation and disaggregation based on event type, agents, and types of groups, as outlined above, in addition to geography, intensity, severity, time, and context.

Coding Process

ACLED’s coding process begins by asking “is this event a violent episode, a demonstration, or a ‘non-violent’ strategic development?” From there, each event is categorized further into one of six event types, and then further into one of 25 sub-event types therein, presented and defined in Table I.5Further definitions of each sub-event type can be found in the ACLED Codebook (ACLED, 2020b).

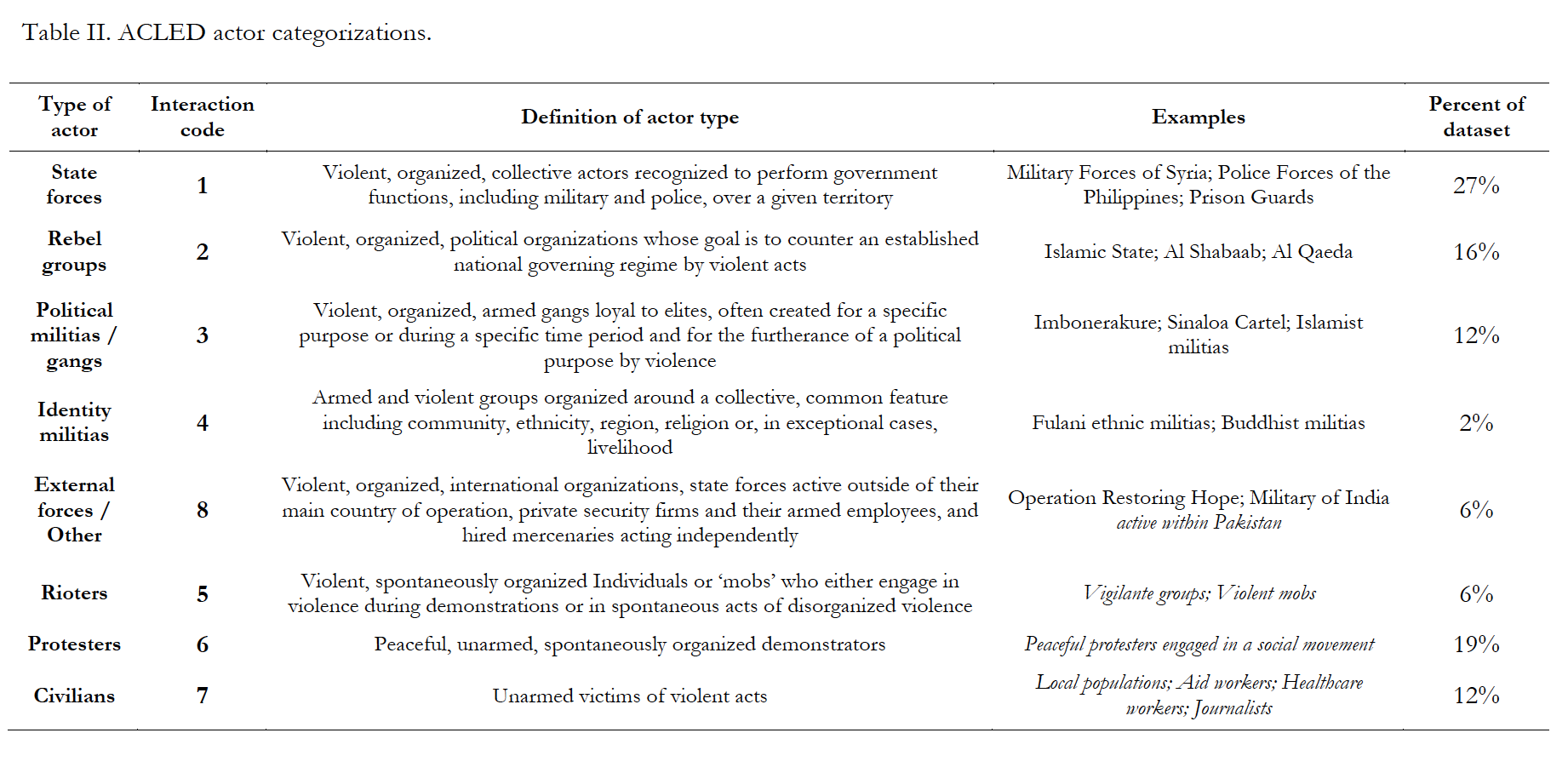

ACLED categorizes ‘actors’ or groups to acknowledge their larger agenda and organizational structure. Actors are designated as one of eight types, including state forces; rebels; political and community militias; civilians; protesters; rioters; or other security forces, including state forces engaging outside of their home country, coalitions and joint operations, peacekeeping missions, etc. (see Table II). Interaction codes, introduced in 2015, note what types of agents are jointly engaging in disorder in any given event. These codes distinguish whether a battle is between state forces and rebels, or between two community militias. They qualify whether an attack on civilians is by domestic state security, or a foreign state force, for example. Classifying engagements amongst actors leads to accurate monitoring of changing dynamics. These advancements are intended to promote data literacy and use amongst the community of users.

While ACLED has extensively developed actors and event typologies, it does not designate ‘conflicts.’ It does not silo or pre-select the ‘type’ of conflict by categorizing and limiting events into ‘civil wars,’ ‘terrorism,’6Consider, for example, how ACLED deals with terrorism and ‘terrorists’. Based on a wide assessment of the circumstances in which these terms are used, and the largely artificial distinctions between the acts of groups deemed ‘terrorists’ compared to groups that are not categorized as such, this term serves to distort the patterns and motivations for violence. Acts of ‘terrorism’ most closely relate to ‘violence against civilians’ in the majority of cases, and can be conducted by governments, rebels, militias or communal groups. That it can be done by all armed, organized groups belies the suggestion that it is based on ideology. ‘election violence,’ or ‘communal violence,’ etc. Problems and inaccuracies are introduced when making grand distinctions and aggregations: if data collection projects make arbitrary designations and cut-offs designed for a research theme, it can distort reporting on how violence occurs within countries by ignoring some forms while promoting others. Second, countries with these aforementioned categories of violence often also have concurrent activity that has little to do with the classification cleavage of a single research question. To designate all violence occurring in a state within a specific arbitrary time period as ‘election violence,’ or to decide that the dozens of armed groups operating in a state are doing so within a dyadic civil war cleavage, is to misrepresent and distort how and why political violence occurs within states, and instead only serves narrow research agendas. These analytical decisions in research have stifled inquiries into how modern political violence is developing, and are unnecessary.

Instead, researchers can extract information and assign these terms – based on ideology, timing, or main dyadic competitors – and justify those decisions per their own individual analysis. To do so requires the researcher to make a choice, rather than data creators dictating that choice. Further, ACLED does not include a reference to the ‘cause’ of each individual action, nor does it predetermine which groups are included based on cumulative fatalities, nor allows fixed definitions of with whom groups can interact. To do so introduces an external bias into event classification, based on the intentions of the researcher; it may also exacerbate the biases of sources, which are prolific.

Fatality numbers are frequently the most biased and poorly reported component of conflict data (Raleigh et al., 2017). Totals are often debated and can vary widely. Conflict actors may overstate or underreport fatalities to appear as stronger contenders or to minimize international backlash. While ACLED codes the most conservative reports of fatality figures to minimize over-counting, this does not account for biases that exist around fatality figures at-large, and this information cannot reliably be used by any data creator to distinguish larger conflicts or conflict agents from each other.7For more information, see ACLED’s fatality methodology document (ACLED, 2020c).

Sources of Information

The breadth and depth of sourcing are the most critical determinants of what version of reality is relayed in conflict and disorder data projects. Two central issues pervade conflict data collection efforts: (1) which combination of media and other information sources can be relied upon, and (2) how to tailor sources to contexts to sustain the best and most reliable coverage. Several studies of traditional and new media suggest that, in combination, both source types cover much of the actively reported events in conflict environments (for example, Dowd et al., 2020).

But information on smaller, peripheral, nascent, complicated, or less deadly conflicts is frequently not thoroughly covered by national or international sources. A wide and deep sourcing net is required and sources of information must be country- and context-specific. The ways in which political violence manifests, level of press freedom, penetration of new media, and domestic politics, amongst other factors, can all impact the extent of coverage in countries and across conflicts. National media may be integral in one context where there is a robust and free press, yet in a more closed press environment, local conflict observatories and new media sources play a more important role. Extensive and accurate information sourcing requires local partners and media in local languages.

ACLED developed several practices to deepen its country-specific sources, including integrating a very wide variety of sources, and an emphasis on local information. ACLED collects reports from over 8,000 sources in over 75 distinct languages, ranging from national newspapers to local radio. ACLED privileges local and subnational sources, relying on the regular review of over 1,500 local and subnational sources worldwide. Further, ACLED researchers often live and work in the environments they cover, and hence benefit from local context, language, and bias knowledge.

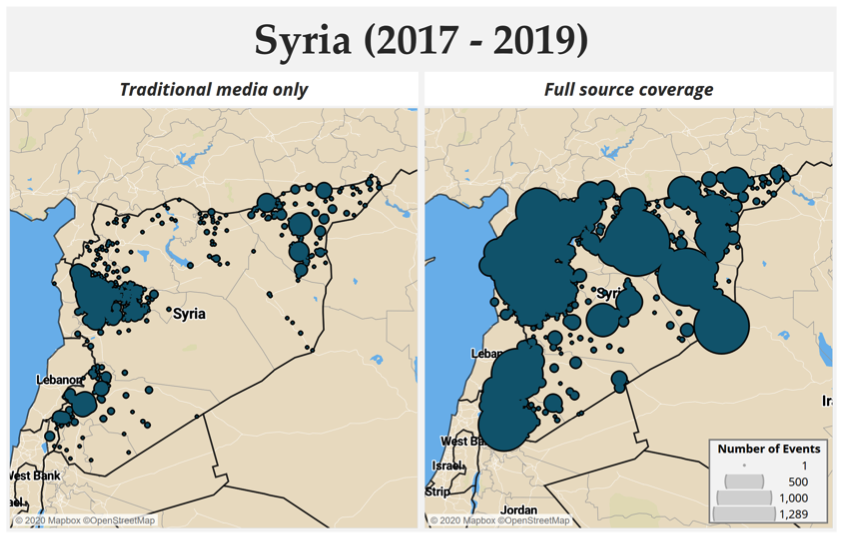

Yet the number of sources is not a metric of reliability. The optimum constellation of sources to capture the range of disorder varies across countries. Consider the example of Syria: Figure 1 notes coverage by source type, depicting the differences that can be seen both geographically (across governorates) and by violence type. The map depicts traditional media on the left, and how its coverage focuses on the capital, Damascus, and surrounding Rural Damascus, in the southwest; on the very active Hama province in the west; and on Al-Hasakeh, where the Kurdish People’s Protection Units and the Syrian Democratic Forces are primarily fighting with other groups in the northeast. The vast majority of information capturing the war against the Islamic State is missed from multiple traditional sources, as the activity is largely occurring outside of the areas well-covered by these media. ACLED information, noted on the map on the right, mainly comes from local partners and sources.

Figure 1. Differences in coverage of disorder in Syria by source.

In addition to the incident reports, variable sources also privilege reporting different types of information in Syria. National media best captures explosions and remote violence, which are prolific in the Syrian context. But local partners and other media improve on that catchment and uniquely capture small-scale battles, violence against civilians, protests, riots, and large-scale arrests by state forces. ACLED’s coverage of Syria has been developed through extensive testing, which helped to yield a targeted subset of sources offering the most complete picture of the conflict with minimal duplication in types of events reported. These sources offer a baseline of coverage, which is then supplemented through targeted enrichment by sources specifically offering coverage of unique event types, actors, and geographies not captured elsewhere (De Bruijne and Raleigh, 2017).

ACLED’s greatest area of advancement is in its partnerships with local conflict monitors, human rights organizations, and media organizations operating in violent spaces. ACLED has supported and extended the capacity of monitors from Thailand, to Yemen, to Zimbabwe, amongst others. It has become a platform for groups in conflict-affected states to provide and publicize their information, including partners across Latin America, South Asia, and Africa. ACLED has established conflict observatories in environments where they did not exist previously, such as the Cabo Ligado project in Mozambique. Partnerships have been established with over 45 local conflict observatories, with more partnerships added regularly. ACLED has built this infrastructure over the past 10 years, and is the only event-based conflict data collection project with such deep and established networks across the world.

Addressing Bias

Media sources and local partners are vetted for known biases, coverage, accuracy, and reliability. Identifying what aspects of ‘bias’ sources may have, and isolating those, is critical. ACLED has found that certain aspects of reporting tend to be more susceptible to bias, such as: whose ‘fault’ an event might be; who ‘started’ a violent encounter; and the number of fatalities, both in total and reported by each side. To avoid such biases, ACLED does not record the former at all in its coding given how these vary largely by the reporting source. On the latter, ACLED errs on the side of recording the most conservative fatality estimates while also regularly highlighting the limitations of fatality reporting, as discussed previously.

Who provides information is a critical question when assessing source bias. Conflict parties have incentives to exaggerate their own achievements, while playing down those of their opponents. At the same time, armed groups do typically report more small-scale skirmishes or assaults in remote areas where more reputable sources lack access. In Afghanistan, for example, there are many places where the Taliban may be the only source for events within their area of control. ACLED, therefore, relies on the same process as with other sources and tests whether a conflict actor provides credible information before including it within the unique sourcing profile for a specific context.8For more information, see ACLED’s sourcing strategy document (ACLED, 2020a).

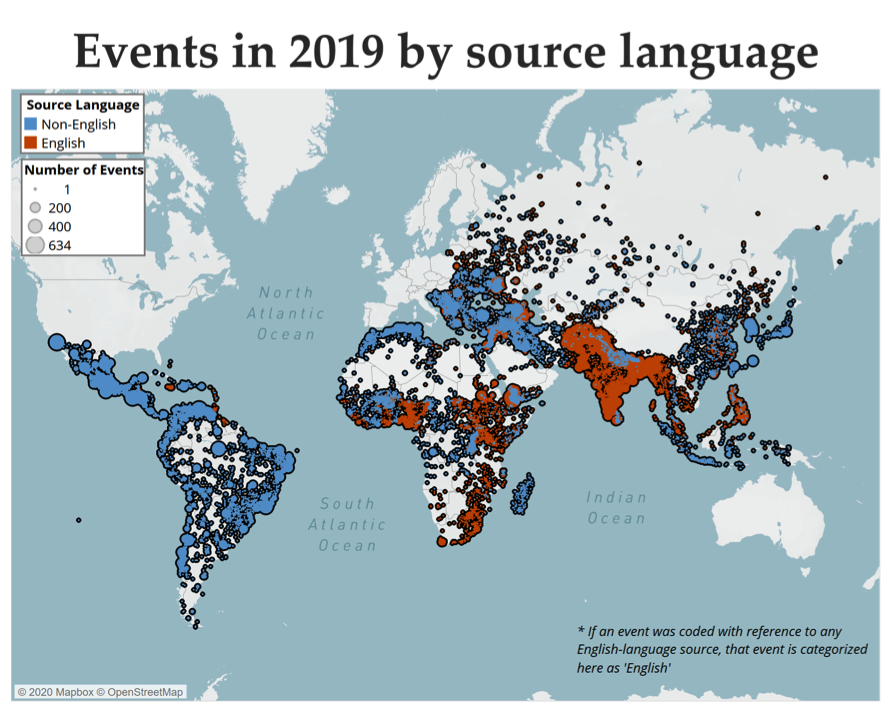

There are inherent biases in choosing one scale of information over another: incorporating local partner information can sometimes involve a tradeoff in how consistently information is conveyed.9ACLED has found that reports by local sources, reputed human rights organizations, and the United Nations generally have more detailed verification processes, and are less prone to conflict biases. They are, therefore, preferred in cases of conflicting details. But the broader ‘narrative’ of conflict emphasized in international media is biased in many different ways: it often tracks large-scale events that are popular to a broad audience, rather than a full and thorough accounting of activity. International sources are heavily skewed towards reporting in English and by foreign correspondents, which incur specific costs in coverage. Foreign and English language correspondents may not be able to access all parts of a country, and are often based in capital cities; this can bring an urban bias to their reporting. English language media may frame conflicts in a certain way, through the use of different lenses based on the primary audience for their reporting — for example, painting a context with certain prejudices or with more editorial coverage (Zaheer, 2016). To correct for these biases, ACLED has amassed over 3,900 sources in local languages, which is complemented by English language coverage. Figure 2 depicts political violence across areas of ACLED coverage distinguished by whether the information collected comes from an English language or a separate local language source. From the map, it is apparent that a reliance on English language sources alone would minimize disorder greatly in certain places where English language media coverage is poor.

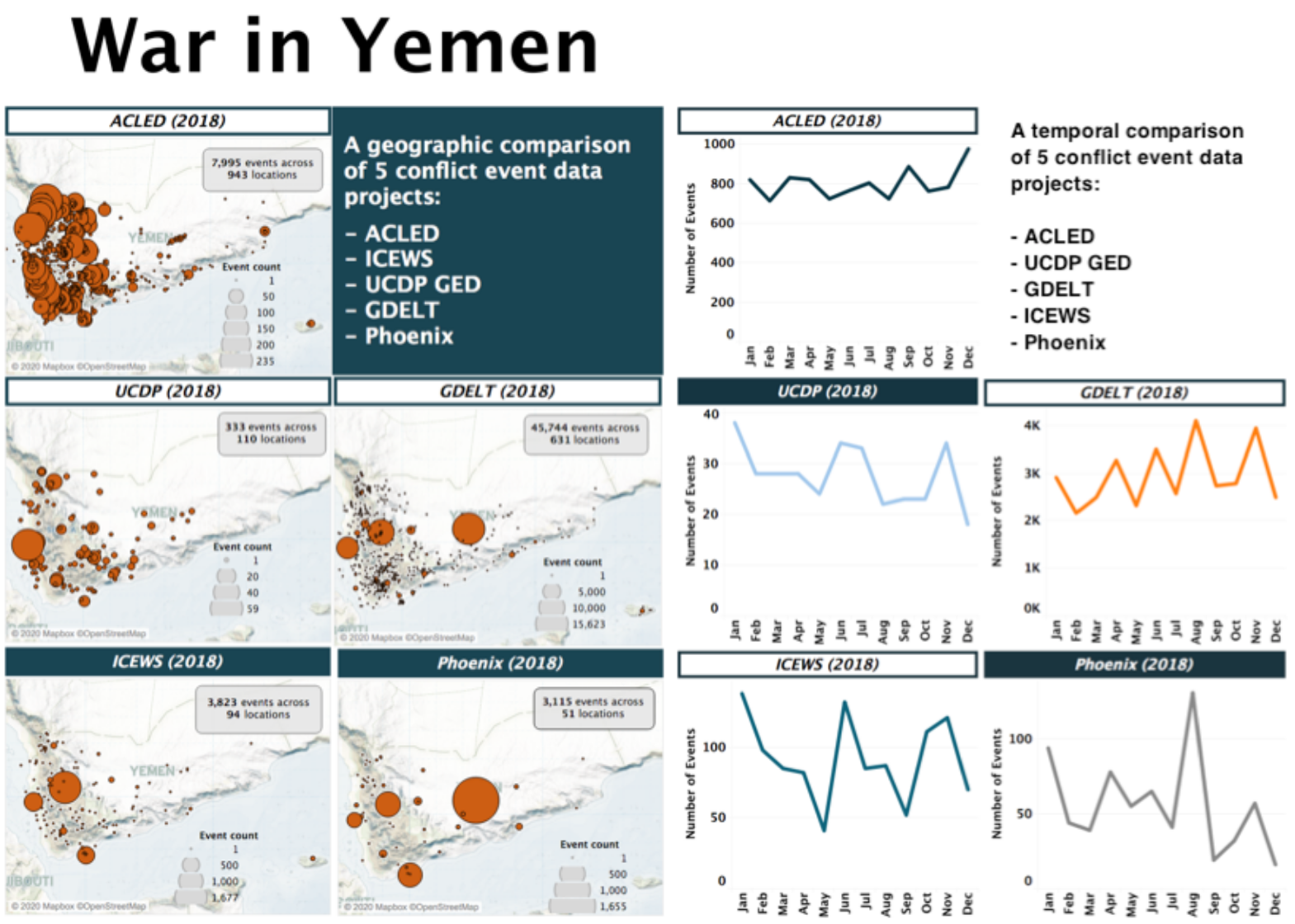

How and from where projects source information is possibly the most important factor in explaining why coverage and data differ across different projects. A data project can only ever be as reliable and accurate as its methodology and sourcing allow. And while no data collection can claim to represent the ‘Truth’ about global disorder, there are variations on how close you can get to the most reliable and robust ‘version of reality.’ As an example, the graphs and maps in Figure 3 compare how a number of different conflict datasets depict the conflict in Yemen in 2018. The graphs’ vertical axes are the number of events reported, and while the intensity and frequency of coverage is not standard across projects, nor do the datasets concur on when the spikes in violence occurred throughout 2018. Most concerning is the general trend in the conflict as the year comes to a close: all of the datasets, except ACLED (top left), report a decrease in conflict in Yemen in December 2018. This reflects how all of the other datasets rely predominantly, if not solely, on English-language media which yield fewer reports across all countries in December, when journalists tend to be away on leave. ACLED’s Yemen data coverage relies on data from local partners and Arabic-language news; neither are affected by this same trend. In turn, ACLED reports a spike in violence in December 2018, in line with the offensive on Hodeidah by the National Resistance Forces on the western front.

The maps depict the geographic scope of the war in 2018. This also varies greatly depending on the lens of reporting. Some datasets suggest a ‘hotspot’ of conflict in the center of Yemen, likely due to datasets using a Yemeni ‘centroid’ point for events where the location of an event is unknown.10Incidentally, this area references Shabwah, which was not an active area of conflict in Yemen in 2018. Others identify the west as the primary arena of violence in the country, largely missing the presence of violence along the border with Saudi Arabia, despite the severity of violence in the Sa’dah governorate, the historical homeland of the Houthi movement.

What Does ACLED Contribute to the Discussion of Conflict?

ACLED event data, collected over 10 years, has contributed to several key lessons about political violence and demonstrations. Modern disorder is complex, interactive, and adaptive, and its patterns are best understood through the lens of violent groups and their forms, rather than as ‘conflict-affected states’ or even discrete events. Rather than explaining conflicts as a dyadic competition, isolated from the politics of states and other violence, disorder is multifaceted, dynamic, contextual, and interactive. Present binary categorizations of violence as ‘civil wars or not,’ or as ‘insurgencies or not,’ ignore the larger context, obscuring how violence agendas adapt throughout the course of a group’s existence in line with the political environment of the state.

When reading a conflict environment through its constituent agents, it is clear that groups differ in terms of their objectives, structure, strategies, persistence, and impacts. For example, ‘rebel groups’ have been declining as the source of most activity for the past 20 years due to changes in the representation structures of governments (Raleigh and Choi, 2020). However, militias operating as armed wings of political elites, have drastically increased their activity – as pro-government proxies (Raleigh and Kishi, 2018), opposition militants, or local political wings. The reason for this change is related to institutional shifts that have invited more elites into the political system, as well as the utility of violence between the powerful. In short: the shift in activities by armed groups reflects the domestic politics of the state, rather than grievances being addressed.

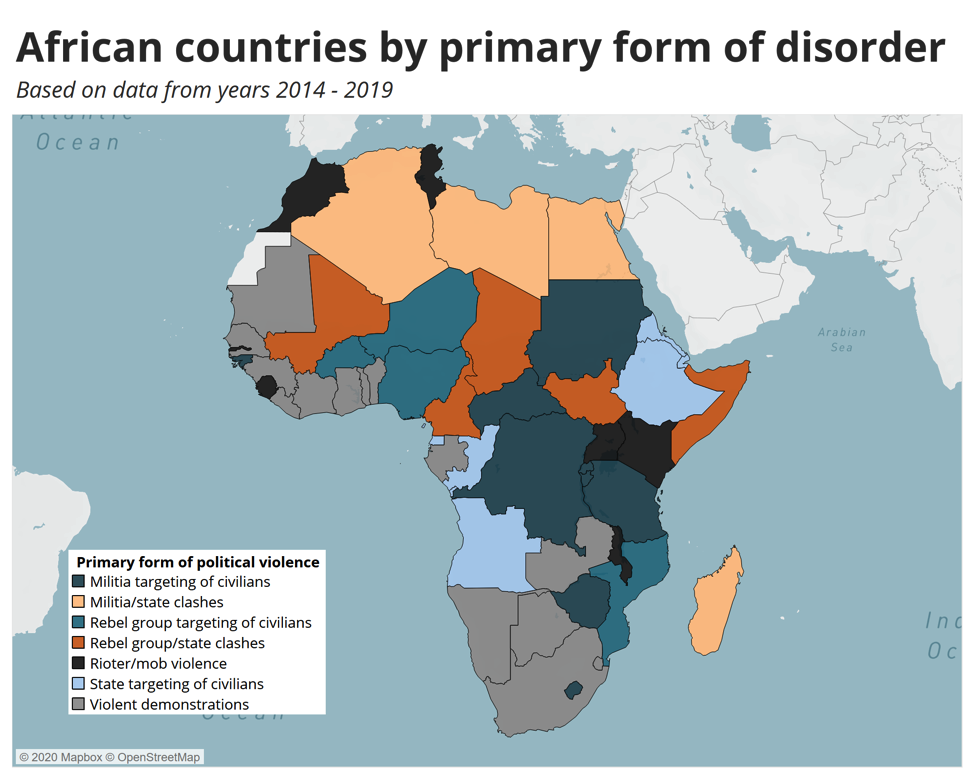

Of course, dominant cleavages can emerge that capture the most frequent events. Consider Figure 4, which depicts the primary form of disorder in each African state in recent years. It demonstrates that disorder may vary widely, and may be distinct from how it is conceptualized in media and academic work. In Nigeria, the primary form of disorder can vary between the ongoing targeting of civilians by various Boko Haram factions or the extensive ‘gang’ activity in the North West; while in South Sudan, the dominant cleavage shifts subnationally from battles between state forces and rebel groups to intra-militia activity. In Zimbabwe, political militias operate as the armed wings of political parties like the ZANU-PF and MDC, regularly targeting civilians; while in South Africa, violent demonstrations are the primary means of engagement in political processes. In many of these cases, the ‘conflicts’ are purposefully fluid, volatile, and subject to political pressures to start or stop. The topography of risk for both states and civilians is therefore far different from the conclusions in the academic literature about ‘grievance-based conflicts,’ ‘insurgencies,’ and repression.

Further, violence by ‘external’, often Islamist agents, has increased as a proportion of overall conflict activity. Event data, rather than rhetoric or narrative, contain important lessons as to why Islamist violence has come to dominante conflict spaces that were previously considered deeply ‘ethnically’ divided. Dowd (2016) notes how Islamist violence across Africa surged where the ability to claim a viable ethnic identity and associated set of grievances was exhausted by many competing armed, organized groups. Islamists could claim a larger communal narrative – such as a religious identity – which cut across ethnic, regional, racial, and economic categories. This speaks less to grievance and more to opportunity and ‘branding’ as significant considerations for armed groups to enter and participate in conflict environments. These actions underscore that conflict groups adapt to local environments in both their forms and the brands that they assume. Recognizing the endogeneity of armed groups and the viable political environment suggests that the dynamics of domestic politics should be of greater interest to conflict scholars.

Through these means, one can capture the dynamics of violence, including non-traditional (and growing) conflicts and the dynamics of change based on how violence benefits groups. Consider the actions in Mexico, where cartels target civilians, often with little to no engagement with Mexican security forces in many areas of the state. These cartels are not seeking to overthrow the state and they are not seeking to establish their own state: they are seeking territorial and population control to pursue economic and violent interests. What is political at the ground level in Mexico may not rise to the ways we conceptualize political violence in academic research, and yet, it concerns de facto governance, population, and territorial control, and alliances of armed, organized groups with legitimate state entities.

The current war in Yemen is yet another example: it can be described as a competition among multiple actors for the control of local and national state institutions. It is the result of several local and national power struggles, aggravated by a regional proxy conflict between Saudi Arabia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). As a result, Yemen’s four intertwined conflicts have caused the deaths of over 125,000 people since 2015. Which is the most fatal, persistent, or controlled is an open question: it could be the conflict between the Houthi movement and the internationally-recognized government of Yemen; the secessionist attempt by the Southern Transitional Council, currently at odds with both the Houthi movement and the internationally-recognized government; a subsiding Islamist insurgency involving Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and the Yemeni branch of the Islamic State, often involving clashes between both groups; and a regional proxy war between Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Iran and, to a lesser extent, Oman and Qatar, each with their own agendas and local allies. These co-occur and are intertwined, yet their causes and motivations are distinct. As a result, the targeting, intensity, diffusion patterns, political networks, and likely mediating effects are equally distinct. Being able to collect information on each discrete conflict is straightforward in ACLED, as is understanding how, where, and under which alliance structures we see intertwined actions and intentions, and when we might see new alliances or rivalries emerge.

Conclusion

Using event data has transformed conflict analysis: information on the range of conflict forms and actors has overturned typical explanations and expected modalities of political violence across the world. Event data tell us that conflict rates and modalities cannot be assumed a priori: event counts are neither higher nor lower based on national or subnational poverty rates, levels of democratization, political exclusion, or grievances. Political violence occurs where there is both high and low economic inequality – such as in South Africa and Ukraine, respectively; where authoritarian politics is reappearing and in states deemed fragile – such as in Hungary and Somalia, respectively; those that have exclusive or static political representation and those that are highly inclusive and volatile – such as in Iran and South Sudan, respectively; and those where ethnicity is a key political identity and where it is not – such as in Ethiopia and Egypt, respectively (Raleigh and Wigmore-Shepherd, 2020). These inconsistencies motivated ACLED’s global expansion but also shaped how ACLED expanded, particularly the details and types of events and conflict agents collected in each country.

As all these examples demonstrate that to understand how conflict manifests and evolves, one must first be able to clearly identify what forms and patterns it assumes locally. To do so, it is vital to know how the politics of a state will make it vulnerable to specific manifestations of disorder. Take one more example: Zimbabwe in 2008. ACLED data show that election-related violence largely occurred between the first and second election rounds, was particularly high in urban centers, and specifically targeted those who had supported ZANU-PF MPs, rather than Mugabe – the ZANU-PF presidential candidate. These findings are only accessible through the work of local partners who collected information and paired it with locally-referenced election results. They stand in contrast to a great number of election studies that assume that opposition supporters are more likely to be attacked than regime supporters. Regimes in transitioning and autocratic states are unstable, and violence is closely related to internal politics (Raleigh and Choi, 2020) rather than to pre-determined measures of poverty, state capacity, demography, or democracy. Locally-sourced event data get us closer to this ground reality.

In short, event data illuminate a range of disorder forms and actors that are under-studied and misunderstood in present academic debates on conflict. The information provided by such event data cannot be ignored. It has both allowed and compelled ACLED to update its components, improve its methodology, and extend its data collection program based on changes on the ground, rather than the stale priorities of existing academic paradigms or the false promise of homogenizing technologies. The result of this effort is the most sophisticated and reliable system of researcher-led data available to the public.

References

ACLED (2020a) FAQs: ACLED Sourcing Methodology. ACLED. (https://www.acleddata.com/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2019/10/FAQs_ACLED-Sourcing-Methodology.pdf).

ACLED (2020b) ACLED Codebook. ACLED. [This resource has been updated, see latest version here: ACLED Codebook]

ACLED (2020c) FAQs: ACLED Fatality Methodology. ACLED. (https://acleddata.com/acleddatanew/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2020/02/FAQs_-ACLED-Fatality-Methodology_2020.pdf).

Davenport, Christian, & Patrick Ball (2002) Views to a kill: Exploring the implications of source selection in the case of Guatemalan state terror, 1977-1995. Journal of conflict resolution. 46(3): 427-450.

De Bruijne, Kars & Clionadh Raleigh (2017) Reliable data on the Syrian conflict by design. ACLED Report. (https://www.acleddata.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/PilotReport_March2018_FINAL.pdf).

Dowd, Caitriona (2016) The Emergence of Violent Islamist Groups: Branding, Scale and the Conflict Marketplace in sub-Saharan Africa. University of Sussex.

Dowd, Caitriona; Patricia Justino, Roudabeh Kishi, and Gauthier Marchais (2020) Comparing ‘New’ and ‘Old’ Media for Violence Monitoring and Crisis Response: Evidence from Kenya. Research & Politics. July-September: 1-9.

Goldstone, Jack (2001) Toward a Fourth Generation of Revolutionary Theory. Annual Review of Political Science. 4(1): 139-187.

Raleigh, Clionadh (2014) Political hierarchies and landscapes of conflict across Africa. Political Geography. 42: 92-103.

Raleigh, Clionadh; Andrew Linke, Håvard Hegre, & Joakim Karlsen (2010) Introducing ACLED: an armed conflict location and event dataset: special data feature. Journal of peace research. 47(5): 651-660.

Raleigh, Clionadh & Daniel Wigmore-Shepherd (2020) Elite Coalitions and Power Balance across African Regimes: Introducing the African Cabinet and Political Elite Data Project (ACPED). Ethnopolitics. 1-26.

Raleigh, Clionadh & Hyun Jin Choi (2020) Inclusion and Political Violence. [Working paper].

Raleigh, Clionadh & Roudabeh Kishi (2018) Hired Guns: Using Pro-Government Militias for Political Competition. Terrorism and Political Violence. 1-22.

Raleigh, Clionadh & Roudabeh Kishi (2019) Comparing Conflict Data: Similarities and Differences across Conflict Datasets. ACLED. (https://www.acleddata.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/ACLED-Comparison_8.2019.pdf).

Raleigh, Clionadh; Roudabeh Kishi, Olivia Russell, Joseph Siegle, & Wendy Williams (2017) Boko Haram vs. al-Shabaab: What do we know about their patterns of violence?. Washington Post, Monkey Cage Blog. (https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2017/10/02/boko-haram-vs-al-shabaab-what-do-we-know-about-their-patterns-of-violence/).

Zaheer, Lubna (2016) War or Peace Journalism: Comparative analysis of Pakistan’s English and Urdu media coverage of Kashmir conflict. South Asian Studies. 31(2): 713-722.