As Myanmar prepares for elections on 8 November, multiple armed conflicts across the country continue. Despite the hope that a government led by the National League for Democracy (NLD) would address the longstanding grievances of ethnic minorities, the past five years have been marked by ongoing fighting between state forces and ethnic armed organizations (EAOs), as well as the suppression of peaceful dissent. Calls to reform the 2008 military-drafted constitution — around which many rallies were held by the NLD prior to the 2015 elections — have lessened. The NLD has settled into a symbiotic, if often fraught, relationship with the military. The likely outcome of the 2020 election — NLD rule for five more years — is unlikely to have a positive effect on conflict trends in the country as ethnic minorities no longer have the same level of trust in, or patience for, the NLD that they once had. The current conflicts in Rakhine and Shan states are likely to continue, while those who peacefully call for an end to the violence will face further repression.

Political Violence in Rakhine and Shan States

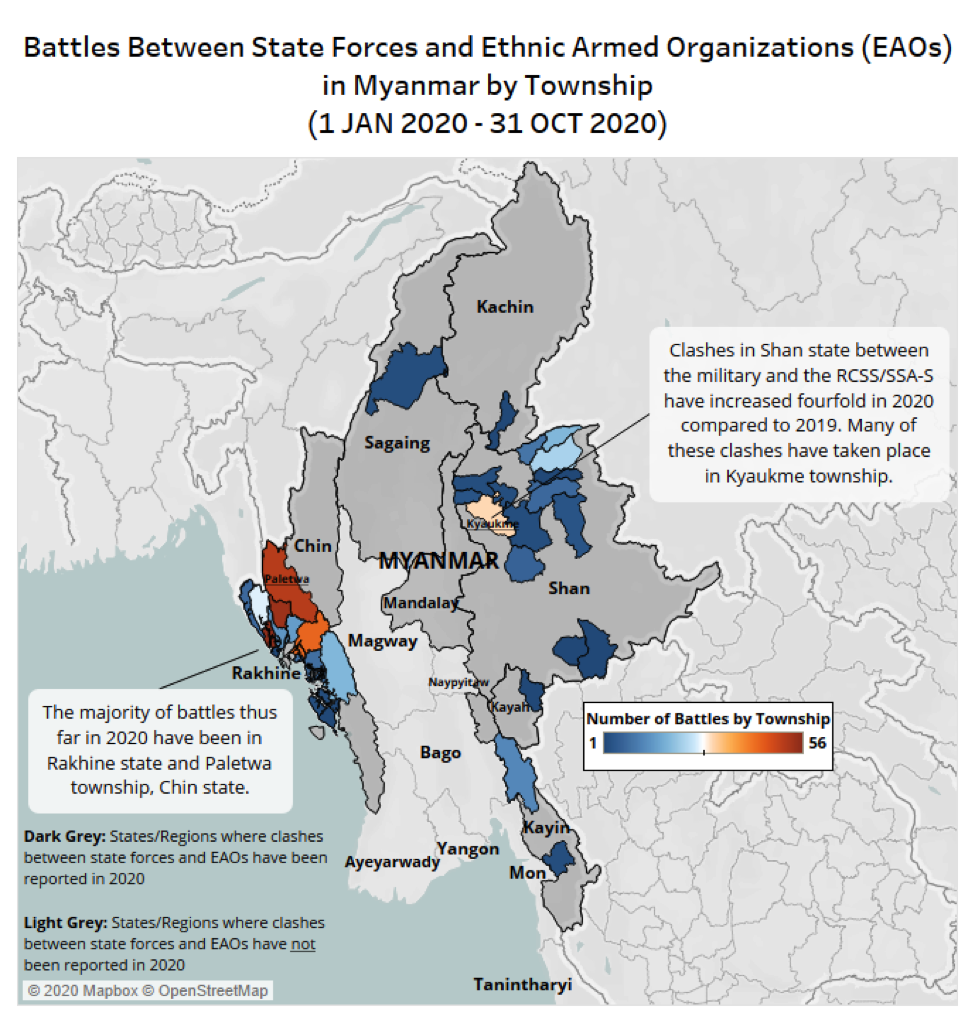

While the military has claimed its goal is “eternal peace” (Global New Light of Myanmar, 10 May 2020), the reality on the ground in Myanmar is one of eternal conflict. The peace process initiated by the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) and continued by the NLD has failed to end fighting across the country. In fact, in the past few years, fighting has increased and shifted to parts of the country that previously had been spared from significant armed conflict. The rise of the United League of Arakan/Arakan Army (ULA/AA), an ethnic Rakhine armed group fighting for greater autonomy, has led to intense battles in Rakhine state and in southern Chin state (specifically Paletwa township). These clashes have been more lethal than other armed conflicts in the country in past years.

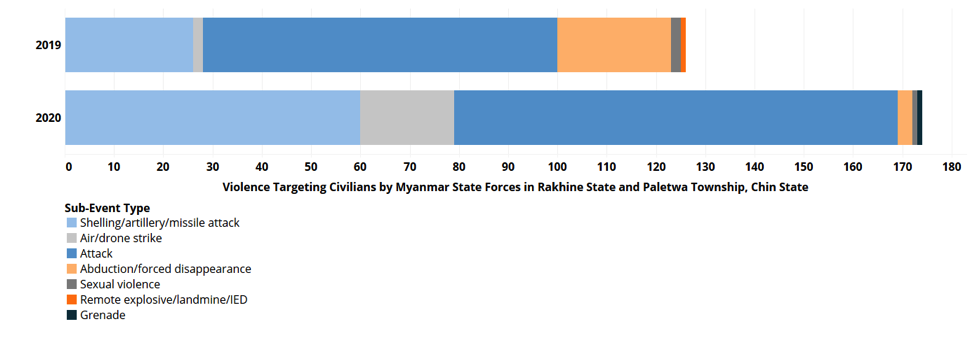

As the military and ULA/AA continue to clash, civilians have not only been caught in the crossfire, but have likewise been deliberately targeted as well (see figure below). ACLED records more than double the number of events of shelling (in light blue below) and airstrikes (in light grey below) by the military targeting civilian areas in 2020 thus far compared to 2019. Most recently, the military fired on an International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) ship on the Mayu river, killing one civilian. The military claimed that ULA/AA members were on the ICRC vessel, which was carrying supplies for displaced civilians in Rakhine state. The ULA/AA, as well as survivors of the attack, have denied the military’s claims (Radio Free Asia, 29 October 2020).

Anti-War Demonstrations

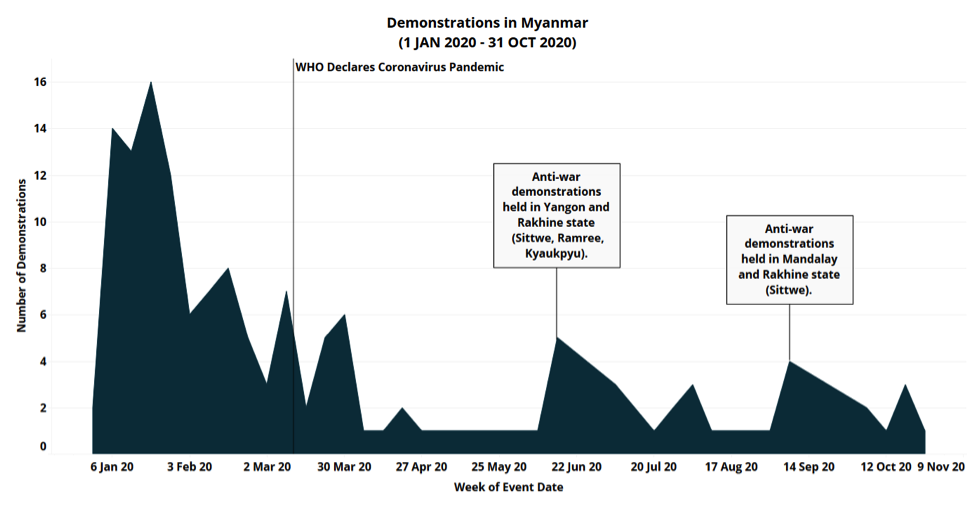

With the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, demonstrations across Myanmar have declined significantly. While sporadic labor protests have been recorded as factory workers face the economic fallout from the pandemic, demonstrations over labor and land issues have largely subsided. The few spikes in demonstration activity recorded during this time have come as youth — mainly university students — have staged demonstrations and organized leaflet campaigns calling for an end to the conflict in Rakhine state (see figure below).

Such demonstrations were held in Rakhine state by the Arakan Students’ Union, reflecting the frustration of many ethnic minority youth (Development Media Group, 9 October 2020). Additionally, demonstrations were held in Mandalay by members of the All Burma Federation of Student Unions (ABFSU), a national-level student group with a history of resistance to military dictatorship. Thus far, two ABFSU members have been sentenced to six years imprisonment while 13 others have been charged for their participation in the demonstrations (Myanmar Now, 21 October 2020). The ABFSU has urged the public to boycott the upcoming elections, arguing that the 2008 constitution undermines the formation of a democratic government (Myanmar Times, 10 August 2020).

The calls for an election boycott have been rebuffed by the NLD and other political parties that emerged from the 1988 pro-democracy demonstrations. However, the youth of Myanmar are not tethered to the same narratives of the past in which the NLD was viewed largely as a force for good. While often overshadowed by the nationalist discourse that has colored the rhetoric of older former pro-democracy activists, there is a contingent of youth activists, including ethnic Burmans, who hold more liberal views. This nascent sentiment, if nurtured, could counter the illiberal environment that has taken hold under the NLD (The Diplomat, 4 November 2020).

Post-Election Prospects for Peace

The post-election period in Myanmar coincides with the end of the rainy season and the start of the dry season, which has traditionally been a time of increased battles in the country. There is little to suggest that the election will impact conflict trends positively. Rather, the uptick in fighting observed in the run-up to the election is likely to continue. The dissatisfaction caused by the cancelation of voting in largely ethnic minority areas threatens to fuel further conflict (for more on this, see this recent ACLED CDT spotlight). The actions and policies of the next government must move beyond a moribund peace process to address the grievances of ethnic minority communities if Myanmar is to see an end to the fighting.