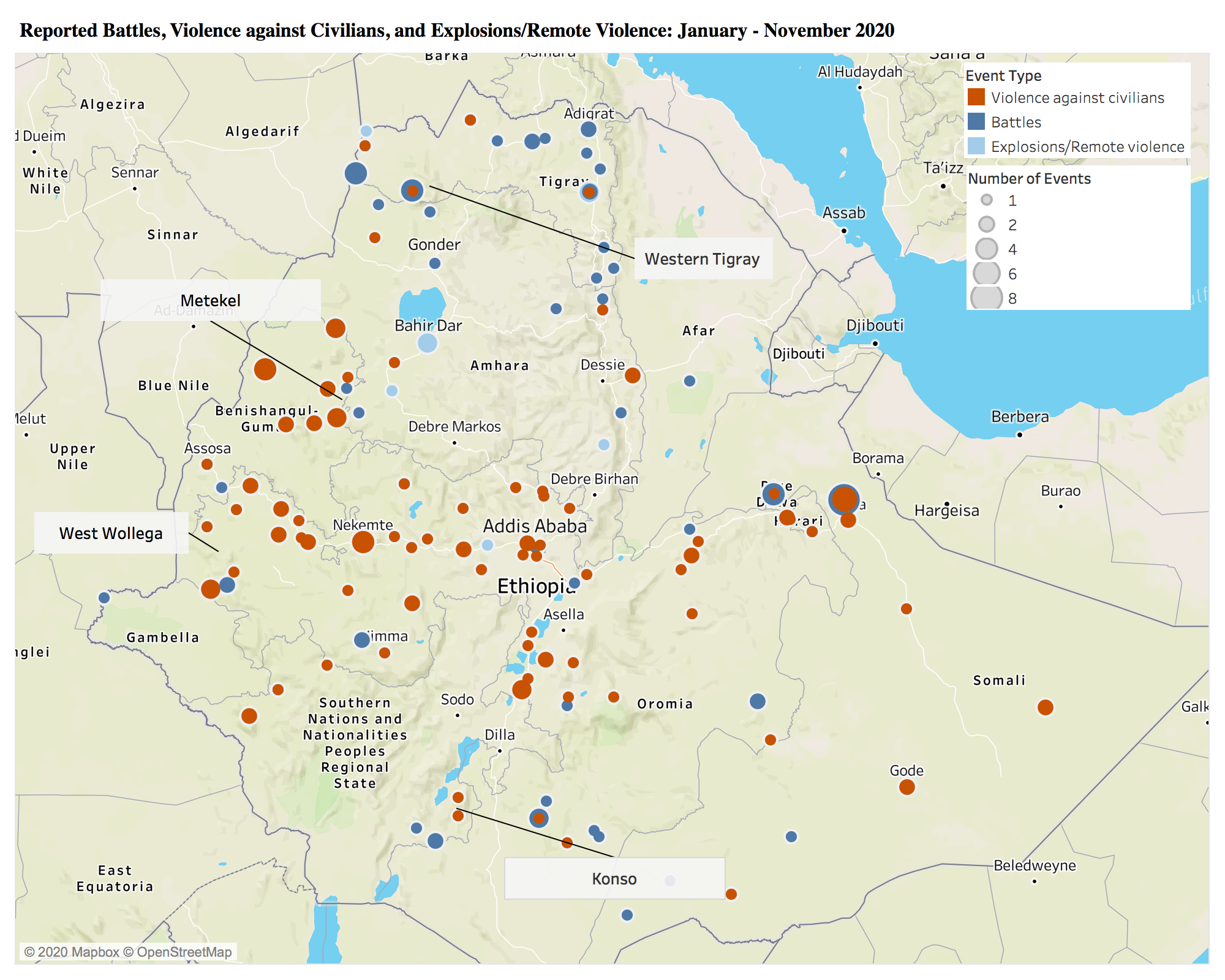

Three weeks of battles in Ethiopia’s northern Tigray region have led to what appears to be a decisive victory for the federal government. On 28 November 2020, an official statement by the armed forces announced that they claimed complete control over the region’s capital city, Mekelle (Abiy Ahmed Ali, Twitter, 28 November 2020). Clashes began on 4 November after months of tension between the central government and the ruling party in Tigray region, the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), culminating in a preemptive strike by the TPLF on the Ethiopian army’s northern command. Directly following the attack, federal troops, bolstered by regional militias from Amhara region, advanced swiftly into TPLF-held territory and took control of Mekelle by the end of the month.

While current conflict trends suggest a clear victory for the Ethiopian government amidst a poor performance by the TPLF, complicated governance issues, a lack of independent media coverage, and the presence of militias with competing agendas portend a turbulent future for Ethiopia’s Tigray region and the country at large.

Tigray Regional Governance

One of the most immediate issues facing the Ethiopian government is the governance of Tigray region. With the removal of the TPLF, nearly all administrators will need to be either replaced or re-structured, posing potential issues with local alignment and resistance.

This is complicated by the fact that the TPLF’s popularity in Tigray region is difficult to gauge. Elections held by the TPLF in defiance of the federal government in September of 2020 resulted in a victory for the party, which claimed an incredible 98% of the votes (BBC, 11 September 2020). Although this certainly points towards the TPLF’s prowess at organizing an electoral victory, it does not necessarily prove popularity as there were no real opposition contenders. In fact, available studies on local governance in Ethiopia suggest that local administrators in Tigray region are little more than extension arms of the TPLF1Fiseha, A. (2020). Local Level Decentralization in Ethiopia: Case Study of Tigray Regional State, Law and Development Review, 13(1), 95-126. doi: https://doi.org/10.1515/ldr-2019-0006 and thus able to easily facilitate electoral success. This vertical structuring of the TPLF down to the local levels will require a complete change in personnel — at least in allegiance — all the way through to the bottom levels of governance.

Some local administrators may be simply recycled and asked to continue their duties as members of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s Prosperity Party, while others may be dismissed. At higher levels, the removal of TPLF officials from their offices began during the first week of the conflict with the stripping of TPLF leaders’ immunity and the appointment of a new regional president (VOA News, 13 November 2020). Initial reports indicate that Amhara administrators and security forces are being utilized as interim directors in areas of Western Tigray, a historically disputed part of the region (France24, 23 November 2020). Their presence could exacerbate already fraught ethnic tensions, and provides a dangerous precedent. Following the massacre of 500 Amhara civilians in Mai Cadra by an ethnic Tigray militia, the Amhara in control of these localities likely see themselves as there to protect their co-ethnic populations rather than uphold the federal strategy and narrative of re-integration (EHRC, 24 November 2020). Any request to return control of these areas to Tigray or federal government control will be met with resistance.

Media Blackout and Insurgency

A general media blackout across Tigray means that international actors know little about the federal government’s strategies for governing the region. It also conceals the damage that may or may not have occurred to civil infrastructure and private homes, and repressive measures taken by security forces against TPLF-linked individuals. Certainly, however, collective punishment of TPLF-linked administrators across the region would generate an engine of anger, resentment, and backlash — which could feed an insurgency.

While international outlets have predicted a large insurgency led by the TPLF, the likelihood of said insurgency is speculation. Despite having preparation, experience, and weaponry, the TPLF have proved to be significantly weaker than the federal government throughout the conflict. The federal government’s ability to use significantly more advanced weaponry including drones, airplanes, and guided missiles appears to have given them a significant advantage. It should also be noted that the Sudan and Eritrea border — used as a major asset during the last TPLF victory in the 1990s — is no longer available, as both countries are allies with Abiy’s central government.

Yet, there remains a more durable threat. Ethnic nationalism is on the rise throughout the country, and there are many armed Tigrayan militias operating in the region who will undoubtedly resist rule by the federal government. As indicated in Mai Cadra, Samri youth militias are capable of serious atrocities, and governing structures appear to hold little control over them. More than a sustained insurgency led by the TPLF, the Ethiopian government is likely to face a long and costly occupation where it competes with militias for control of localities. Imposed administrators in the Tigray region will likely not possess the political leverage and communal control that their TPLF predecessors did, meaning that they will require significant federal assistance in maintaining stability.

The ability of the government to sustain a lengthy occupation is complicated by the multiple separate insurgencies that are occurring in Ethiopia. Although these see little international press, armed clashes in remote regions of the country threaten to spread government security resources thin. Last week, armed conflict in Konso lead to the displacement of 94,000 people (Addis Standard, 23 November 2020). The government holds little control in West Wollega, where it is battling members of the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA). Communal clashes in Gujji have killed hundreds, and armed ethnic militias continue to attack civilians in Metekel despite the presence of federal troops in the area (Africa News, 16 November 2020).

The next few months will be critical in shaping Ethiopia’s future. The federal government faces many threats, including armed insurgencies across multiple locations in the state. As the country gears up for the scheduled 2021 elections, Abiy’s leadership will be questioned by many of those around him. His response to these crises will affect his ability to succeed in the upcoming vote, as well as the viability of the federal government’s continued control over the country.