Reviewing new ACLED data for the past seven months of political violence and demonstration activity across the US, this report analyzes key trends in right-wing mobilization and the potential for violence in the post-election period. Access data directly through the US Crisis Monitor. Definitions and methodology decisions are explained in the US Crisis Monitor FAQs and the US methodology brief. For more information, please check the full ACLED Resource Library.

Introduction

More than 150 million Americans cast ballots in the 2020 presidential election, setting a new record even as the COVID-19 crisis intensified (CNBC, 4 November 2020). Despite the heightened risk of political violence going into the vote (NPR, 22 October 2020), government officials, civil society organizations, and local communities organized to address the threat, with limited interference on Election Day and a peaceful resolution by the end of the week, as former Vice President Joe Biden was projected by national media to be the victor (VOA, 7 November 2020).

The results were immediately disputed. Tensions increased as it became apparent that a decisive outcome would be delayed beyond Election Day due to logistical challenges posed by the pandemic. Current President Donald Trump declared without evidence that the election was being “stolen,” prompting a surge in protests outside vote-counting centers as well as threats against election officials (PBS, 17 November 2020). On the right, tensions persist amid a combined legal and disinformation campaign to discredit the process and to overturn Biden’s victory. According to a late November poll from the Economist and YouGov, almost 90% of Trump voters believe the election result is illegitimate (Economist, 21 November 2020),1Compared to 23% of Hillary Clinton’s supporters in 2016, and 36% of Al Gore’s supporters in 2000. a finding echoed by a range of concurrent surveys (Newsweek, 10 November 2020; Politico, 9 November 2020). And just 27 of 249 Republicans in Congress — or 10% — have acknowledged Biden’s win as of early December (Washington Post, 5 December 2020). As the president refuses to concede, hundreds of ‘Stop the Steal’ protests have been organized across the country, in which militias2Around the world, ACLED defines militias, which are a large and diverse range of actors, as armed and organized violent groups that are extra-legal — meaning they are, by definition, extra-military, extra-state, non-institutional entities. While some of these groups may be pro-government, they need not be. Those which are pro-government often only have indirect links to the state, yet may mobilize and operate with the assistance of important allies, including factions within the state. “[Pro-government militias] are made possible by a political culture that allows for unaccountable agents and actions. They present a serious threat because of the support they receive from state elites allowing them to perpetrate violence on behalf of those elites with impunity” (Raleigh & Kishi, 2018). ACLED chooses to use the same terminology — the word ‘militia’ — for all regions of global coverage, particularly to underline the consistencies in the activities and incentives of such actors across geographic regions. For more on ACLED definitions, see the ACLED Codebook. and armed actors have taken an enlarged role. Members of right-wing armed groups like the Oath Keepers have announced that they will never recognize a Biden presidency, and are committed to resisting the administration’s policies (Independent, 15 November 2020).

While the legal pathways to a second term have all but entirely closed for President Trump, with recounts confirming Biden’s win and court cases producing no evidence of mass voter fraud, he has not formally conceded. Although the Trump administration has allowed the Biden team to begin the transition process, the president continues to hold rallies against the so-called “rigged election” and has called on Republican legislators in states like Georgia to appoint pro-Trump electors to the Electoral College (ABC News, 7 December 2020). Under these murky circumstances, where Trump supporters believe they have either lost the election or are at high risk of seeing the election stolen, right-wing mobilization is likely to spike relative to a clear electoral defeat and concession.

Building on the assumption that backers of a losing candidate are more likely to mobilize during the post-election period — particularly when a subset of the losing candidate’s support base is organized, armed, and has a demonstrated capacity for violence — this report analyzes the potential for persistent right-wing unrest through the inauguration and beyond. Reviewing new ACLED data3ACLED coverage of the US has now been extended to the start of May 2020. Access here. covering the past seven months of political violence and demonstration activity, the report tracks key shifts in unrest from the start of the summer to the election and its aftermath. The risk of political violence in the coming weeks will be shaped by the type and degree of organized right-wing opposition to the incoming administration, as well as the efficacy of peacebuilding and violence mitigation efforts aimed at reducing polarization, fighting disinformation, and bridging partisan divides. ACLED analysis identifies four main trajectories through which right-wing mobilization could lead to violence in the post-election period (see table):

- If right-wing demonstrations are limited largely to militia groups, especially national movements, then the risk of large-scale violence increases, namely events with multiple active shooters. This scenario is more likely in locations where mobilization is linked to local militia groups with histories of high levels of activity.

- If demonstrations primarily involve the mass mobilization of decentralized, armed individuals, then the risk of small-scale, individualized violence will increase. This is a more likely scenario in locations experiencing left-wing protests or where new gun regulations are under consideration by local or state governments.

- If demonstrations are frequently targeted by violent sole perpetrators, as seen in a rise in concurrent or post-protest car rammings, aggressive individual attackers, or ‘leaderless resistance’ modalities, then the risk of widespread individualized violence will increase. This is a more likely scenario in sites of sustained political uprisings or enduring local tension — such as areas where well-organized Black Lives Matter or leftist activism has persisted beyond the summer and into the fall.

- If demonstrations are predominantly driven by unarmed mass mobilization of broadly unaffiliated, and heterogenous right-wing protesters, then the risk of lethal violence will decrease, while the risk of street-fighting, especially brawls with counter-protesters, will increase. This scenario is unlikely to manifest for sustained periods of time, but is more likely to take hold in areas where local and national actors perceive high levels of election fraud.

Potential trajectories for right-wing mobilization and violence in the post-election period

| Trajectory | Likelihood (Short-term) | Likelihood (Medium-term) | Violence Potential | Highest Risk Locations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Militia groups | Low | Moderate | Low to Moderate | Locations where mobilization is linked to local militia groups with histories of high levels of activity (e.g. Lansing, Michigan) |

| Decentralized armed individuals | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Locations experiencing left-wing protests or where gun restrictions are under consideration by local or state governments (e.g. Richmond, Virginia) |

| Violent sole perpetrators | High | High | High | Areas that have sustained uprising activity or enduring local political tension (e.g. Portland, Oregon) |

| Unarmed mass mobilization | Very High | Very High | Low | Areas where election fraud is perceived by local and national actors (e.g. Atlanta, Georgia) |

Shifting Trends: Pre- and Post-Election

Dominant Protest Movements

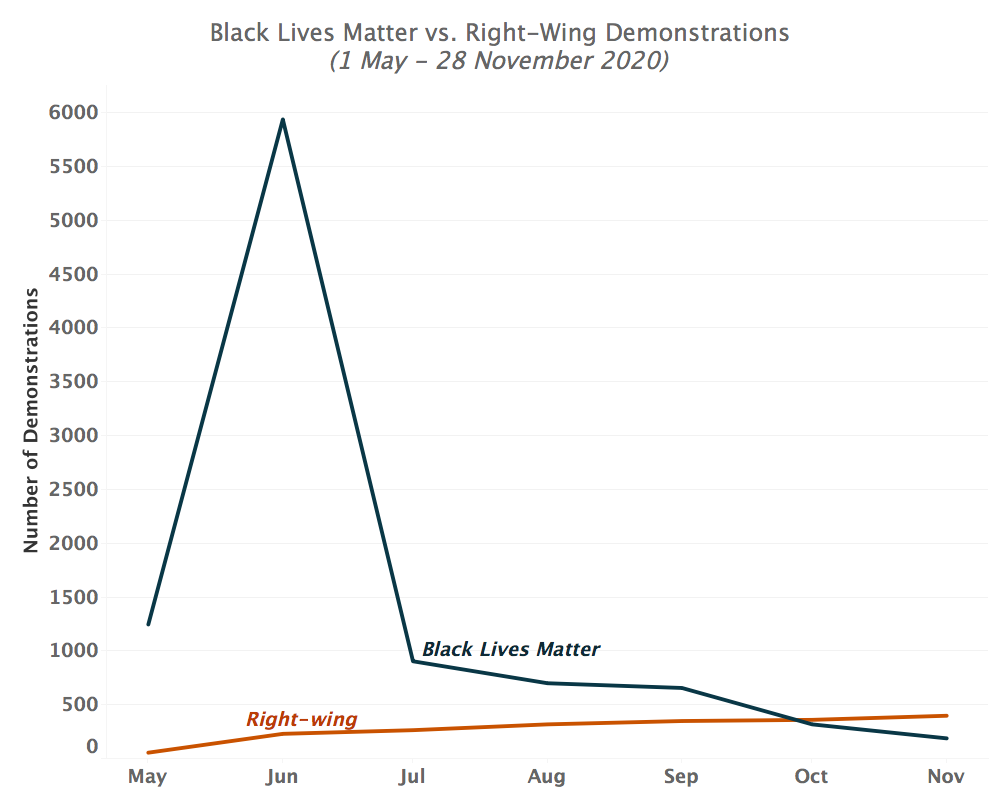

Demonstrations surged over the summer ahead of the general election, particularly in the immediate aftermath of George Floyd’s killing by police in Minneapolis. Floyd’s death at the end of May sparked a new phase of protests associated with Black Lives Matter (BLM), a movement challenging police violence and structural racism in America, which led to thousands of demonstrations around the country. While media coverage has focused on cases of looting and vandalism, fueling right-wing disinformation campaigns aimed at mischaracterizing BLM activists as “violent extremists” (ADL, 2020), the vast majority of demonstrations associated with the movement have remained peaceful. Although ACLED data indicate that 94% of these demonstrations have involved no violent or destructive activity as of late November,4This activity includes violently disruptive and/or destructive acts targeting other individuals, property, businesses, other rioting groups, or armed actors. Such demonstrations can involve engagement in violence (e.g. clashes with police), vandalism (e.g. property destruction), looting, road-blocking using barricades, or burning materials like tires, among other activities. It is important to note that this category includes events where violence may have been initially instigated by the demonstrators as well as events where violence may have been initially instigated by police or other actors engaging the demonstrators. For more information on definitions and methodology, see the US Crisis Monitor FAQs. a contemporaneous Civiqs poll measuring support for BLM found that 38% of total respondents — and 47% of white respondents — were opposed to the movement, even as support has remained high among Black and Hispanic communities (Civiqs, 29 November 2020). A similar poll in mid-September found that just 16% of White Republicans expressed support for the movement (Pew Research Center, 16 September 2020).

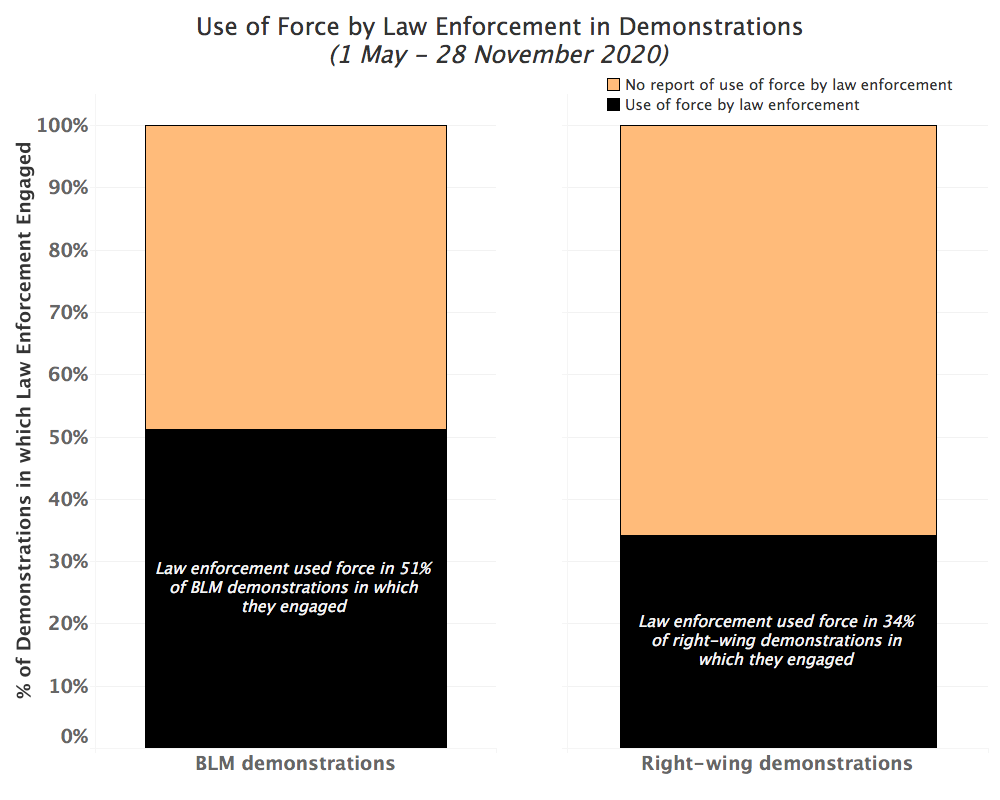

Against this backdrop, demonstrations associated with the BLM movement have been disproportionately met with government intervention compared to other types of protests. When authorities have engaged BLM-linked demonstrations, they have also disproportionately used force to disperse the demonstrators (for more information, see ACLED’s report on demonstrations and political violence trends throughout summer 2020). Thousands have been arrested in what activists have decried as a “deliberate crackdown” (Al Jazeera, 16 November 2020), with reports that those detained have faced excessive charges threatening long prison terms, a “suppression tactic” used to discourage mobilization (The Guardian, 16 August 2020).

Under pressure from the heavy-handed state reaction, the number of demonstration events associated with the BLM movement has declined in the weeks and months following Floyd’s death. Such a response — particularly the use of force against demonstrators, harsh consequences for those arrested, and intimidation by armed extra-legal actors like militia groups — can alter the incentives of participants in mass movements like BLM. Due to factors like protest fatigue, social movements are rarely able to sustain high levels of mass mobilization over time. In light of these trends, the diminished levels of BLM-linked demonstration activity since the initial spike in May is not surprising (see navy line in graph below). Nevertheless, demonstrations associated with the BLM movement continue, and have taken on a very local focus in recent weeks — such as multi-day protests in Omaha, Nebraska in response to the death of Kenneth Jones;5Kenneth Jones was a Black man shot by two Omaha police officers during a traffic stop on 19 November (NBC News, 23 November 2020). The incident occurred during a traffic stop initiated by the two officers after they spotted a car with four occupants stopped in the middle of the road without emergency flashers activated. According to police, after Jones failed to comply with verbal commands to put his hands in the air, the two officers forcibly pulled him out of the car (KETV, 24 November 2020). One of the officers then reportedly saw a gun on Jones, prompting the officers to fire four shots at him (NBC News, 22 November 2020). demonstrations in Albuquerque, New Mexico calling for a thorough investigation into the case of Rodney Applewhite;6Rodney Applewhite was an unarmed Black man killed by police on 19 November during a traffic stop while driving through rural New Mexico to his mother’s house in Arizona for Thanksgiving. Police allege that Applewhite attempted to reach for the gun of an officer, though no further details have been provided (Santa Fe New Mexican, 30 November 2020). and protests in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma calling for justice in the case of Stavian Rodriguez.7Stavian Rodriguez was a 15-year-old Latino teen killed by police after a failed armed robbery. Video of the incident appears to show Rodriguez with his hands up and his weapon on the ground when several shots were fired at him (KOCO, 25 November 2020).

Meanwhile, right-wing demonstrations (see inset box for definition) have followed a different pattern, both in levels of activity and state response. Right-wing mobilization increased in the lead-up to the election and surpassed the number of BLM-linked demonstrations (see brown line in graph below). Yet right-wing demonstration activity has been met with very limited government intervention, underscoring how these events consistently face low levels of force, rare arrests, minimal legal consequences, and infrequent intimidation by armed extra-legal entities,9On 3 December, Grand Master Jay, the leader of the Not Fucking Around Coalition (NFAC), was arrested on federal charges for allegedly pointing a gun at officers stationed on a roof in downtown Louisville during his group’s gathering on 4 September (Associated Press, 3 December 2020). While the NFAC is an armed, organized, extra-legal group, it is distinct from most other militias in the US context in that it is a burgeoning Black separatist movement that, in many ways, is a direct reaction to many right-wing groups. The arrest of Jay is a rare example of an alleged ‘militia’ member being arrested for activities that took place at a demonstration in which they participated. Other arrests of predominantly white militia groups, like that of the Wolverine Watchmen, arrested for the plotted kidnapping of Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer (Associated Press, 8 October 2020), are often tied to either actuated violence or an alleged unity of purpose towards committing violence in the future. Even the armed Black movement known as BLM757 based out of Richmond, Virginia shared in a press conference in Newport News, Virginia that they were only allowed to speak without intervention outside of a police precinct because of Boogaloo Boi Mike Dunn’s militia on the scene (News2Share, 15 October 2020). Relatedly, in the same state, a mostly white gathering of 2nd Amendment activists and militia groups gathered in Richmond at the beginning of the year for a Lobby Day event organized by the far-right Virginia Citizens Defense League (VCDL) and actively broke local gun ordinances while police looked on (Reuters, 20 January 2020; MilitiaWatch, 16 April 2020). The VCDL is already planning a similar engagement in 2021, for which militia and other right-wing activists are likely to show up, this time for a car rally (Virginia Star, 30 November 2020). particularly when compared with their left-wing and BLM counterparts. Armed and violent contingents like the Proud Boys, who previously responded to President Trump’s order to “stand back, stand by” (Associated Press, 30 September 2020), have declared that the standby order has been “rescinded” in the post-election period (Forbes, 7 November 2020). Street-fighting has broken out at multiple demonstrations involving Proud Boys around the country since the election, including in North Carolina, New York, California, and Washington, DC (Daily Kos, 3 December 2020).

Demonstrations associated with the right-wing have been met with law enforcement intervention far less frequently relative to BLM-linked demonstrations: under 4% of events, compared to nearly 10% of events. When authorities have engaged demonstrations associated with BLM, they have used force — such as firing less-lethal weapons like tear gas, rubber bullets, and pepper spray or beating demonstrators with batons — more than 51% of the time, compared to only 34% for right-wing demonstrations (see graph below).10As noted above, nearly 94% of demonstrations associated with the BLM movement involved no violent or destructive activity as of late November, meaning that such activity was reported in 6% of demonstrations. It is important to note that this 6% includes both those demonstrations in which demonstrators may have engaged in such activity, and were then met with use of force by authorities, as well as cases in which law enforcement used force against peaceful protesters who only responded violently as a result of police engagement. Provocative activity by law enforcement — such as showing up to peaceful events with riot gear, or using tactics like kettling in which protesters are cornered — has been common. ACLED does not systematically code these dynamics, including who initiated violence, given the limitations and biases in reporting on these factors (though available information is included in the ‘Notes’ section in ACLED data). Notably, even if all demonstrations in which BLM-associated demonstrators reportedly engaged in looting, vandalism, or violence are excluded from analysis — if the assumption were to be that the use of force by authorities under such circumstances is ‘warranted’ — nearly 5% of all peaceful BLM-linked protests were met with law enforcement intervention, and over 37% of these events saw the use of force by authorities. In comparison, less than 3% of peaceful right-wing protests were met with law enforcement intervention, and only 18% of these events saw the use of force by authorities. These trends suggest that government intervention and use of force are not merely set responses to demonstrator behavior, but rather part of a broader attitude, policy, or strategic approach to different types of mobilization in different local, state, and national contexts.

Armed Group Activity

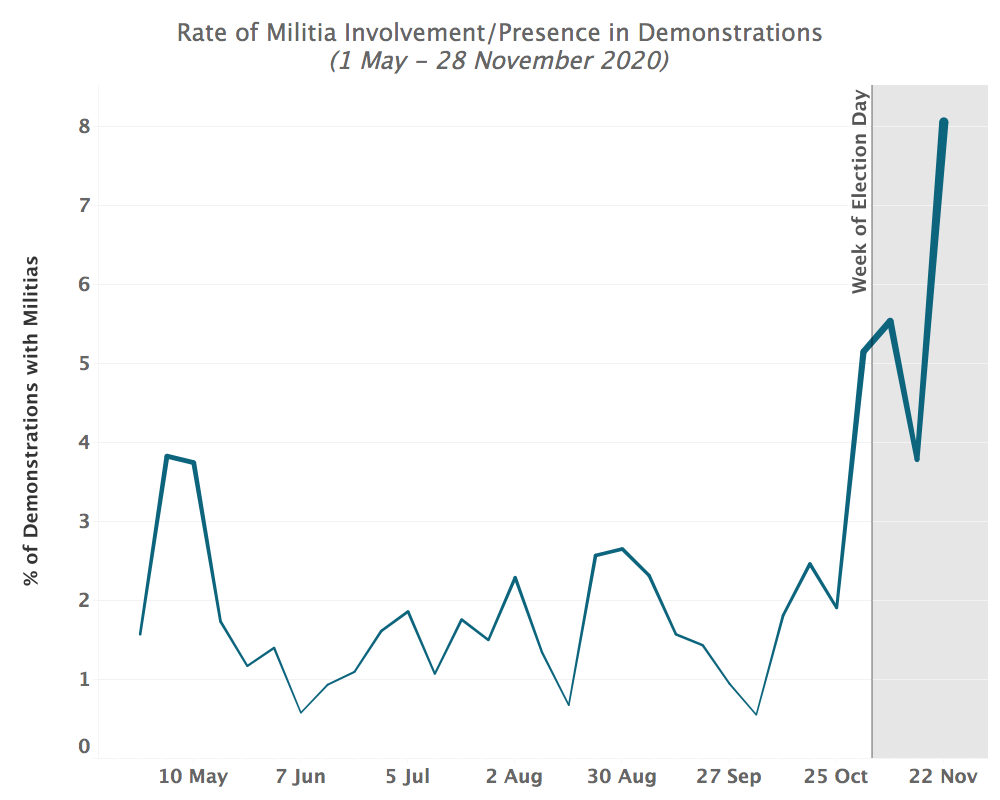

Militias and street movements have become increasingly active in right-wing demonstrations this year. Over the summer, right-wing militias primarily mobilized in response to the BLM movement and pandemic-related public health restrictions. In the run-up to the election, militias additionally organized around perceived threats to the sanctity of the election such as mass voter fraud, with groups like the Oath Keepers warning that they would arrive at polling stations and use violence if necessary to “protect” the vote from being “stolen” (Media Matters, 28 October 2020; NPR, 31 October 2020). A proactive approach by civil society groups and government officials aimed at preventing the threat of armed intimidation at the polls — including an “extremism crackdown” by federal law enforcement in Michigan (Detroit News, 29 October 2020) and the arrest of a Proud Boys member who threatened to blow up a polling location in North Dakota (Daily Beast, 30 October 2020) — may have reduced the risk of violence and resulted in limited militia activity on Election Day (USA Today, 3 November 2020).

Compounding the effects of increased attention and preventative measures aimed at mitigating the risk of militia activity at the polls, the strategic incentive for these groups to ramp up operations on Election Day itself decreased as the vote approached, particularly compared to the pre- and post-election periods. This is in part due to their overriding focus on perceived attacks against the sanctity of the election, such as ‘deviations’ like mass mail-in voting during the pandemic. Large-scale violence against polling centers on Election Day would undermine that sanctity and challenge the right-wing narrative that in-person voting was more valid than mail-in voting — a narrative pushed by the Trump administration, which actively discouraged voting by mail based on debunked allegations that the process is exceptionally vulnerable to fraud (Washington Post, 11 September 2020). Trends suggest that those voting in person on Election Day were disproportionately Republican supporters, with Democrats being more likely to have taken advantage of mail-in or early voting (FiveThirtyEight, 28 August 2020; The Hill, 15 September 2020), diminishing the incentive for militia groups to target polling centers filled with ‘legitimate’ right-wing voters on Election Day.

ACLED analysis of militia activity during elections around the world finds that these incentives change over the course of the electoral period: before the vote, armed groups have an incentive to intimidate and suppress voters, while afterward this incentive shifts to challenging election results and ballot counting. Joint research conducted by ACLED and MilitiaWatch prior to the US election outlined multiple factors that raise the risk of militia activity before, during, and after the vote, including perceptions of leftist coup activities — i.e. ‘stealing’ an election — as well as highly competitive votes in swing states — i.e. states where vote counting appears to be very close or delayed (for more, see the ACLED and MilitiaWatch joint report). Many of these drivers emerged on or after Election Day, contributing to the rise in right-wing protest activity in the aftermath of the vote and the increased role for militia groups within these demonstrations.

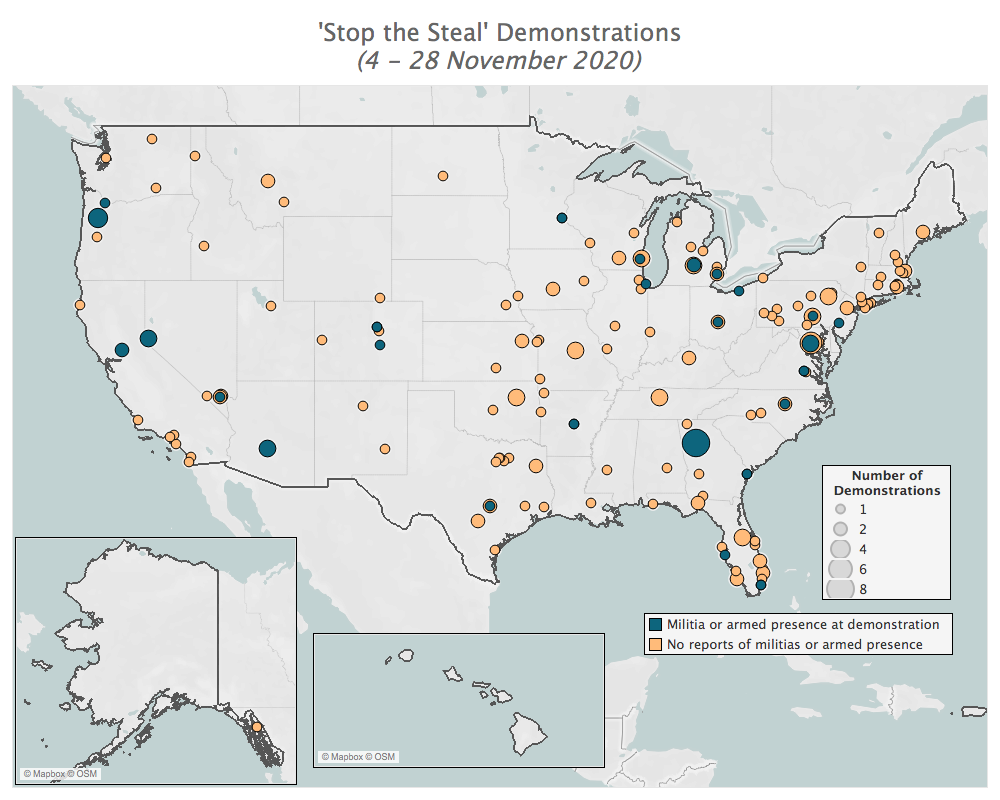

Late on the night of the election, when the preliminary results began to indicate that President-elect Biden was likely to win, President Trump sent out a tweet claiming that the vote was being “stolen,” without presenting evidence (Vox, 4 November 2020). In response, a ‘Stop the Steal’ demonstration campaign quickly took form, with participants demanding the rejection of votes perceived to be illegitimate, such as predominantly Democratic mail-in ballots (see map below). These demonstrations, encouraged by the executive branch and many right-wing media outlets, rapidly spread across the country, often met with counter-protesters calling on officials to ‘Count Every Vote.’11Many ‘Count Every Vote’ rallies were pre-planned ahead of election week in anticipation of a long vote-counting period, while others emerged as counter-protests to ‘Stop the Steal’ demonstrations. Militias and armed individuals have been disproportionately active in ‘Stop the Steal’ demonstrations compared to other demonstrations.

While demonstrations involving militias peaked in June in terms of gross numbers and then declined, they have since surged to roughly the same level in November. Right-wing mobilization is often posited as ‘reactive,’ in that it occurs in response to mobilization by the left. In June, the increase in involvement by right-wing militias in demonstrations can be seen as a reaction to the mass mobilization of the BLM movement (i.e. ‘leftist organizing’) — demonstrations associated with the BLM movement were at their height in the weeks following Floyd’s killing at the end of May. Meanwhile, in November, the spike in right-wing militia involvement in demonstrations can be seen as a reaction to perceived ‘leftist coup behavior’ in the form of an attempt to ‘steal the election.’

Unsurprisingly, ‘Stop the Steal’ demonstrations have been disproportionately competitive compared to other types of demonstrations, meaning that a high number of counter-protests, such as ‘Count Every Vote’ rallies, have also been present. Nearly one-third — or 32% — of ‘Stop the Steal’ demonstrations have involved counter-protests.12If two protests occur at the same time, in the same place, and they are essentially ‘counter’ to one another, then the events are coded as a single event instead of as two separate events. While ACLED will code the two parties, ACLED does not code which side may have shown up first, or who is countering whom. Such information is limited and often biased in reporting. To the extent such information is noted in sources, it will be noted in the ‘Notes’ section of the data for users. Discussion of ‘counter-protests’ here refers to cases in which ‘Stop the Steal’ demonstrators showed up to protest and ‘counter’ another group as well as cases in which ‘Stop the Steal’ demonstrators were protesting and others showed up to ‘counter’ them. It is a measure of how ‘competitive’ such demonstrators can be, especially relative to demonstrations around other issues. Sometimes, other parties, such as police, may get involved in counter-protests — on behalf of one side or the other, or to ‘keep the peace.’ In such cases, police may be coded as one of the primary actors; ACLED defaults to coding the more important engagement in each event. Nevertheless, all events that capture a counter-demonstration include a ‘tag’ in the ‘Notes’, stylized as “[counter-protest]”, which can be used to identify all counter-demonstrations. For answers to frequently asked questions about ACLED coding methodology in the US context, see these FAQs. This contrasts with only 9% of all ‘Count Every Vote’ demonstrations, less than 6% of demonstrations associated with the BLM movement, and just over 5% of demonstrations at large.

Potential Trajectories

The current trends in political violence and demonstration activity in post-election America are not a direct continuation of the trends identified over the summer: there has been a significant shift in the leading protest actors, the involvement of armed groups and individuals, and how they are in turn met by the authorities. Likewise, ACLED data do not indicate that these current trends will remain static through to the inauguration and initial stages of the next administration. The risk of political violence and unrest in the coming weeks will be shaped by the type and degree of organized right-wing opposition to the incoming administration, as well as the efficacy of peacebuilding and violence mitigation efforts aimed at reducing polarization, fighting disinformation, and bridging partisan divides. ACLED analysis identifies four main trajectories through which right-wing mobilization could lead to violence in the post-election period:

- If right-wing demonstrations are limited largely to militia groups, especially national movements, then the risk of large-scale violence increases, namely events with multiple active shooters. This scenario is more likely in locations where mobilization is linked to local militia groups with histories of high levels of activity.

- If demonstrations primarily involve the mass mobilization of decentralized, armed individuals, then the risk of small-scale, individualized violence will increase. This is a more likely scenario in locations experiencing left-wing protests or where new gun regulations are under consideration by local or state governments.

- If demonstrations are frequently targeted by violent sole perpetrators, as seen in a rise in concurrent or post-protest car rammings, aggressive individual attackers, or ‘leaderless resistance’ modalities, then the risk of widespread individualized violence will increase. This is a more likely scenario in sites of sustained political uprisings or enduring local tension — such as areas where well-organized Black Lives Matter or leftist activism has persisted beyond the summer and into the fall.

- If demonstrations are predominantly driven by unarmed mass mobilization of broadly unaffiliated, and heterogenous right-wing protesters, then the risk of lethal violence will decrease, while the risk of street-fighting, especially brawls with counter-protesters, will increase. This scenario is unlikely to manifest for sustained periods of time, but is more likely to take hold in areas where local and national actors perceive high levels of election fraud.

(1) Demonstrations limited largely to militia groups

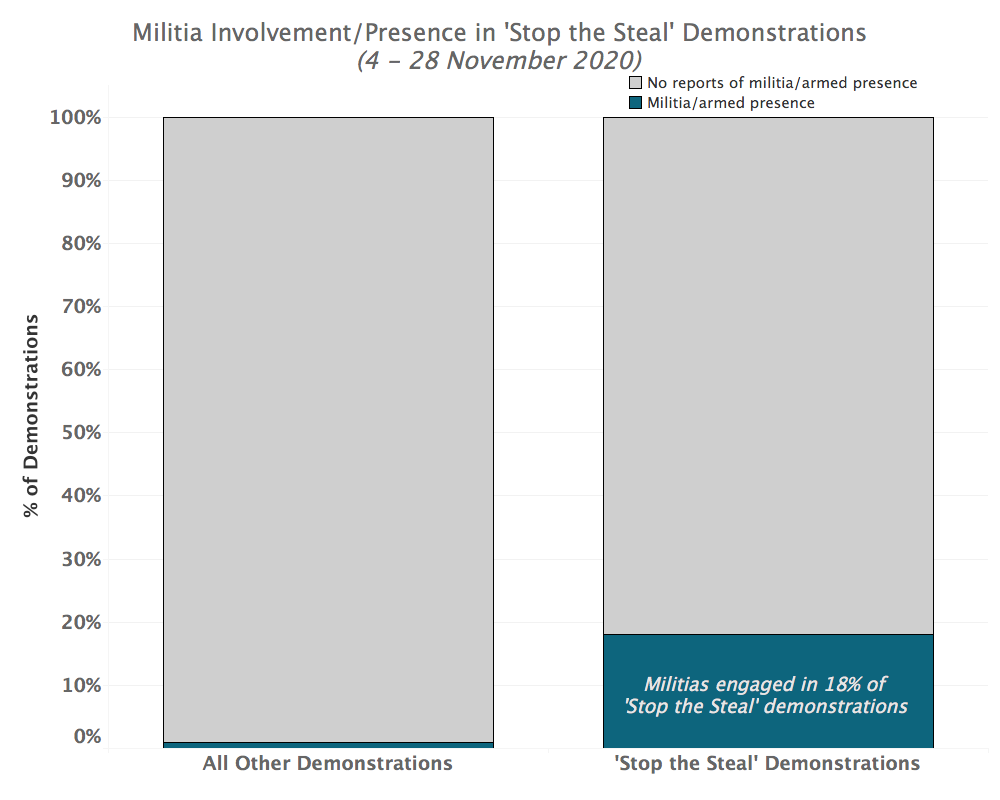

If right-wing demonstrations are limited largely to militia groups, then there will be a higher risk of mass violence.13A higher risk is not equivalent to actual occurrence and does not convey certainty. Rather, the assessment indicates that there is a higher possibility or probability of an occurrence. Looking to lessons learned from contexts elsewhere in the world, large numbers of highly organized, mobilized, and armed individuals will increase the likelihood of mass violence. This is especially the case if national movements become increasingly involved in demonstration activity. National groups, especially relative to local, non-affiliated movements, tend to be more extreme ideologically among their members. With ‘Stop the Steal’ demonstrations, there has already been disproportionate engagement by militia groups relative to other protests: militia groups have participated in 18% of all ‘Stop the Steal’ demonstrations, while they have engaged in less than 1% of all other demonstrations (see graph below).14While the trend is already clear, it is surely an undercount: many militia groups are organizing and attending these demonstrations outside of the mantle of their ‘public militia affiliation’ and instead as more quotidien unarmed protesters. This is likely due to a mix of reasons, from the additional organizational energy required to show up as a militia group, individual interests to show up at a protest not solely as an armed supporter, and the perceived urgency to join street or caravan movements. One other reason for this is the existence of ‘gun-free’ zones or areas that do not allow open carry — areas that without major organizing usually dissuade people from showing up armed to protest. For example, the day after the election, in Phoenix, Arizona, a member of AZ Patriots entered the Maricopa County Recorder’s Office by impersonating a member of the press, live-streaming an allegation that the county had used a sharpie to invalidate ballots before being removed from the building. Following this allegation, more than 200 people — including members of AZ Patriots and III%ers, among others — rallied outside the ballot-counting facility in support of President Trump, alleging that some ballots had been improperly counted (Washington Post, 5 November 2020). The following day, Proud Boys were reportedly present at a ‘Stop the Steal’ protest in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (WHYY-FM, 5 November 2020; Twitter, 5 November 2020).

In addition to engagement in demonstrations, the number of recruitment and training events involving militias also remains higher than average relative to the last seven months. As some militia groups have involved themselves directly in the ‘Stop the Steal’ movement — such as the III% Security Force and the Oath Keepers — this concurrent rise in recruitment and training is to be expected given its strategic advantage.

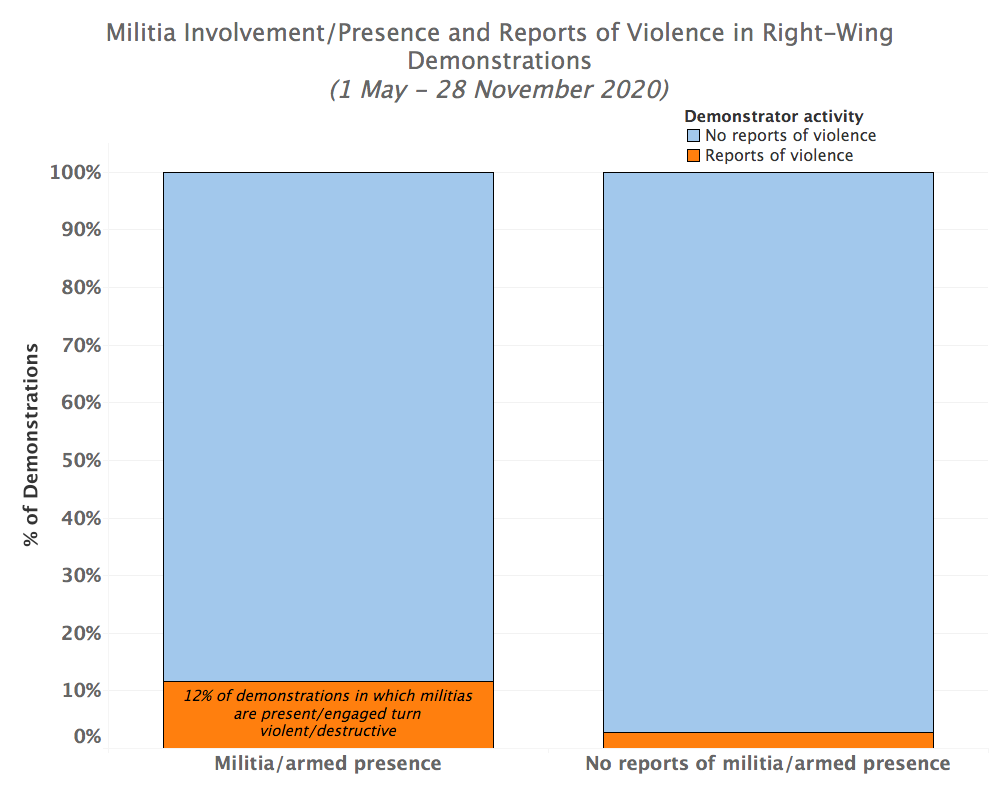

Current trends indicate that when militias are involved in right-wing demonstrations, the demonstrations tend to turn violent or destructive more frequently — 12% of the time — relative to other right-wing demonstrations in which militias are not directly involved — less than 3% of the time (see graph below). In this sense, the presence of a militia at a demonstration increases the risk of violent or destructive activity even before the event begins.

There are signs that this pattern could change. ‘Stop the Steal’ demonstrations, and election-related demonstrations more largely, are attracting multiple militia groups, with participants either organizing in tandem or organically responding to the same event as a mobilizing factor. New coalitions are likely already being built during these rallies — which have put online fascists and militia leaders in the same organizing space once more (see section below on Unarmed Mass Mobilization). Online communications on and around local and national elections for many of these communities have been rife with call-to-action posts and discussion of the need to ‘get organized,’ and their adherents are highly electrified at the possibility of a ‘leftist coup’ (see section below on Mass Mobilization of Decentralized, Armed Individuals).

(2) Mass mobilization of decentralized, armed individuals

If demonstrations involve the mass mobilization of decentralized, yet armed, individuals, then there will be a higher risk of small-scale, individualized violence. This is especially the case if mobilization increasingly takes the form of ‘muster calls’ or armed ‘calls to action.’ Cases where armed and primed individuals have responded to networked calls to action have resulted in multiple shooting incidents targeting opposing demonstrators in recent months. Examples include Kyle Rittenhouse’s response to a muster call by the Kenosha Guard in Wisconsin in late August (New York Times, 16 October 2020), or Steven Ray Baca’s response to a muster call by the New Mexico Civil Guard in Albuquerque, New Mexico in June (The Guardian, 17 June 2020). While such violence has so far been small in scale and scope, it has proven lethal.

While this type of lethal violence has yet to become a feature of the post-election period, the risk of escalation is significant. Since the election, armed individuals have demonstrated the willingness to respond to calls to ‘stop the steal’. For example, two armed QAnon supporters were arrested outside a vote-counting center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania for carrying handguns without a license after driving there from Virginia two days after the election. Some reports indicate that they intended to deliver fraudulent ballots to the center (CNN, 7 November 2020). Their traveling from a distance to ‘support the cause’ highlights the draw of broad calls to action.

The following day in Detroit, Michigan, police investigated a bomb threat outside of a voting center where absentee ballots were being counted amidst rival pro-Trump and pro-Biden demonstrations (FOX2 Detroit, 6 November 2020). A similar incident was also reported in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on 6 November (The Independent, 6 November 2020), as well as death threats targeting election officials with reminders that “this is what the Second Amendment is for” (Philly Voice, 9 November 2020).15Violent threats against poll workers and election officials have continued well past the vote in key swing states. According to a PBS investigation in mid-November: “The exact number of incidents of poll-worker intimidation is unknown. But a FRONTLINE review, based on questions to a dozen election and law enforcement agencies in five swing states, as well as local media reports, found examples of threats or acute security risks to election workers in Pennsylvania, Nevada, Michigan, Arizona and Georgia” (PBS, 17 November 2020). Such incidents underline how calls to action can inspire those not formally affiliated with organized groups. Similarly, in mid-November, a number of people, including some armed with assault rifles and handguns, gathered in Johnson Square in Savannah, Georgia for a ‘Stop the Steal’ event (Savannah Now, 21 November 2020). Despite no reports suggesting these individuals were part of an organized militia, local or otherwise, the call to ‘stop the steal’ still served to inspire them to take up arms and ‘join the fight.’

In the past, this type of mobilization has typically occurred around ‘Second Amendment Rallies,’ wherein supporters are asked to show up armed to a demonstration, often on the steps of a capitol building or in direct response to policy, proposed or otherwise. For example, this year, a series of pro-Second Amendment, pro-militia, and anti-lockdown protests have been reported in and around Lansing, Michigan. These began in the early days of the coronavirus pandemic, in response to public health restrictions, and have continued through the election period. These types of mobilizations provide an important on-ramp for recently radicalized individuals, or those who have become prone to commit violence without the social accountability of a more organized group, even if such accountability structures are typically weak. Many actors in this space also consider local law enforcement as at least tacit allies in their efforts to ‘quell riots’ or ‘protect property.’ These actors range from militia groups like the Oath Keepers, who showed up in Louisville, Kentucky to ‘assist’ police and ‘guard’ gas stations around protests over the Breonna Taylor case,16Police killed Breonna Taylor, a 26-year-old Black woman and paramedic, in Louisville, Kentucky last March during a botched raid on her apartment (New York Times, 1 September 2020). The lawsuit filed by Taylor’s family alleges that police raided the “wrong house,” and the targeted suspect had already been located elsewhere, while authorities have maintained that their warrant allowed them to search the premises as well and claim the raid in question was intentional (AP, 7 July 2020). The search warrant application is currently under investigation by the FBI. to more local groups like the gathering of armed vigilantes in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho ahead of fears of a rumored Antifa action.

Importantly, this trajectory focuses on networked ‘calls to action,’ though is in line with a more decentralized response system. Muster calls, lobby days, declarations of restitution, and other calls to action tend to precede these events. This serves to make such incidents more predictable for policymakers and local law enforcement. In this way, it is distinct from the trajectory described below (Increasing Attacks by Violent Sole Perpetrators). The latter is more sporadic and less predictable, making its likelihood in both the short- and medium-term — as well as its potential for violence — higher.

(3) Increasing attacks by violent sole perpetrators

If demonstrations increasingly come under attack by violent sole perpetrators, there will be a higher risk of widespread individualized violence and disorder. This type of incident — including car rammings, individual assaults, or ‘leaderless resistance’ modalities — have become more common since May, and especially in support of President Trump around the election.

Car-ramming attacks have become increasingly common in the US, especially relative to other countries (NPR, 21 June 2020) — a trend that is at particularly high risk of intensifying given encouragement online (e.g. “All Lives Splatter” memes) (Bloomberg, 3 June 2020) and the major emphasis on ‘Trump train’ and caravan/convoy demonstrations in recent right-wing mobilization. In these types of demonstrations, supporters, usually in pick-up trucks, drive into and through towns, often making threats from their vehicles or online, and sometimes even intentionally ramming counter-protesters. Those engaging in these demonstrations are also often armed, which heightens the risk of violence (Vanity Fair, 7 December 2020; Washington Post, 1 November 2020). For example, two days before the election, a pro-Trump car caravan rally was held in Richmond, Virginia, with counter-protesters also present nearby (Richmond Times-Dispatch, 2 November 2020). While no injuries were reported, violence ensued. Some pro-Trump supporters sprayed chemical irritants at the counter-protesters. Witnesses report shots being fired, with at least one pro-Trump supporter allegedly firing a gun at a counter-protester. Another counter-protester stated that he narrowly avoided being run over by one of the vehicles participating in the caravan.

While car rammings have not been a tactic used exclusively by the right-wing — for example, in late July, several demonstrators taking part in a ‘Defend the Police’ rally, organized by the Northern Colorado Young Republicans, were hit by an SUV in Eaton, Colorado (Greeley Tribune, 25 July 2020) — they have disproportionately targeted the left.

‘MAGA Drag’ events, as they are often termed around and beyond the election, have resulted in several high-profile events, aside from individual car-ramming attacks. For example, the week before the election, a group of drivers supporting President Trump surrounded a Biden/Harris campaign bus on a stretch of highway outside of Austin, Texas. Pro-Trump supporters, many of whom were armed, surrounded the bus on the interstate and attempted to drive it off the road (CNN, 1 November 2020). One of the drivers hit a Biden campaign staffer’s car. The event, which caused the Biden campaign to cancel an event in nearby Pflugerville due to safety concerns (Texas Tribune, 31 October 2020), was “celebrated” by President Trump, who tweeted his support for those who had swarmed the bus (NPR, 1 November 2020). Since the vote, in mid-November, during a protest against the president while he was golfing at Trump National Golf Club in Sterling, Virginia, a pro-Trump counter-protester forcefully exhaled on two women demonstrators after they commented that he was not wearing a face mask during the pandemic. The Trump supporter was later charged with misdemeanor assault amid coronavirus concerns (Politico, 23 November 2020).

Individualized violence and intimidation is also common outside of these contexts, in the form of hate crimes. In recent weeks, ACLED has recorded multiple cases of property destruction targeting specific ethnic, religious, and political groups. In Alabama, unidentified assailants perpetrated an arson attack against a business owned by the leader of the local BLM chapter (WBRC, 12 November 2020), though there were no reports of anyone hurt in the incident. In Texas, the mailbox of a pro-Biden couple was spray-painted with swastikas weeks after all of their Biden-Harris signs were destroyed (KLTV, 16 November 2020). Likewise, a swastika painted on a newspaper was left outside the office of a left-leaning news outlet in Kentucky. Furthermore, the Jewish Center at the University of Kentucky was vandalized after the Rabbi claimed to have received death threats. In November, the FBI reported that hate crimes in the US rose to their highest levels in over a decade last year (AP, 16 November 2020).

Importantly, this trajectory focuses on how individual actors, outside of more ‘firm networks,’ may use gatherings to commit violence or to intimidate political rivals. Such gatherings can serve as a platform or area of operations for individuals prepared to commit violence or disorder to follow through on their ideation, often as people are leaving marches or after protests disintegrate. In this way, this trajectory is distinct from the one described above (Mass Mobilization of Decentralized, Armed Individuals). It is more sporadic and unpredictable, making its likelihood in both the short- and medium-term, as well as its potential for violence, higher than the former, which relies on networked ‘calls to action’ through a more decentralized response system.

(4) Unarmed mass mobilization

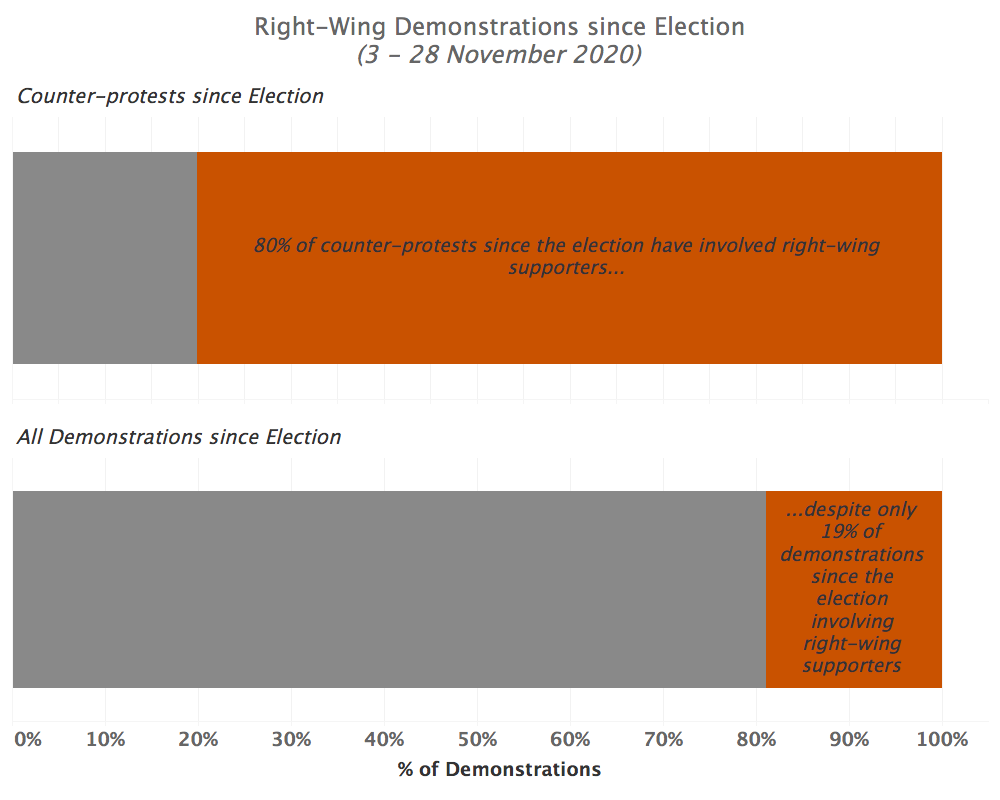

If demonstrations represent mass mobilization of unarmed, non-militia — or otherwise broadly unaffiliated — and heterogenous right-wing individuals, then there will be a lower risk of lethal violence, and yet a higher risk of street-fighting, especially brawls with counter-protesters. Right-wing demonstrations are highly competitive, and counter-protests disproportionately involve right-wing supporters. Approximately 19% of all demonstrations in the US since the election have been right-wing, but right-wing activists have participated in more than 80% of all counter-protests during the same period (see graph below).17It is important to remember that not all demonstrations can be categorized as right- or left-wing (i.e. the fact that less than 19% of demonstrations since the election have been right-wing does not mean that over 81% have been left-wing). For example, a large proportion of demonstrations in recent weeks have been related to the coronavirus pandemic (for more, see this recent infographic from ACLED’s COVID-19 Disorder Tracker). While some of these can be categorized as right-wing (e.g. those involving armed right-wing groups challenging the state’s authority to mandate mask-wearing) or as left-wing (e.g. those admonishing the Trump administration’s handling of the pandemic), others cannot be easily categorized as such. For example, a protest involving restaurant staff advocating against coronavirus restrictions so that they can get back to work is not necessarily ‘right-wing,’ and a protest involving healthcare workers advocating for more access to personal protective equipment (PPE) to keep them safe is not necessarily ‘left-wing.’ Many of these types of demonstrations do not cite involvement by a right- or left-wing group, and sources do not report protesters making right- or left-wing claims. As such, the specific political stance of such protests cannot be definitively known — and is hence not grouped into right-wing or left-wing categories for this analysis. For definitions and methodology information about counter-protest events, see footnote 12 or the US Crisis Monitor FAQs.

In addition to a space to protest, these demonstrations also provide networking and recruitment opportunities. A collection of right-wing ideologies have been present at these demonstrations: a coalition of convenience and common purpose. It includes the likes of InfoWars, a right-wing conspiracy news site headed by Alex Jones, who has a history of involvement in street rallies; to the Groyper Army, Nick Fuentes’ most recent evolution of the America First traditionalist, neo-fascist movement; to viewers of One America News Network (OANN), a far-right media outfit friendly to Trump and pro-Trump writers; to QAnon, the conspiracy theory originating from 4Chan users, detailing Trump’s fight against the ‘deep state’ that opposes Trump and connects to theories that powerful Democrats run a secret pedophilia ring for the world’s elite; to Proud Boys and other armed groups; and beyond.

These groups have already come together at protests since the election. On 14 November, thousands of Trump supporters made the trek to Washington, DC to participate in a large ‘Stop the Steal’ event called the ‘Million MAGA March.’ Attendees included hundreds of unarmed, unaffiliated protesters as well as groups like the Proud Boys, the Oath Keepers, Boogaloo Bois, the III%ers, QAnon, and the American Guard, among others, who were in turn met by counter-protesters, including BLM supporters and antifascists, among others (BuzzFeed, 15 November 2020). While the march during the day was largely peaceful, rioting and fighting between the right and left was reported both before and after the march, including fist fights; use of clubs and projectiles; setting off fireworks; spraying of irritants; multiple stabbings; and a car-ramming attack (Washington Post, 15 November 2020). Days later, a multi-day protest was held in Atlanta, Georgia, attracting hundreds of people. Right-wing influencers like Alex Jones of InfoWars, Nick Fuentes of Groypers, and Enrique Tarrio of the Proud Boys, among others, were in attendance. Demonstrators marched into the state capitol as part of a ‘Stop the Steal’ event amid Georgia’s high-profile recount (Daily Mail, 18 November 2020). Several participants held ‘We are Q’ signs, in support of QAnon, and ‘thin blue line’ flags, expressing support for law enforcement. The group was met by a small group of counter-protesters, including BLM and Antifa supporters, among others (11Alive, 21 November 2020).

Such networking and recruitment across group identities has the potential for further ideological escalation into the future. Given the local nature of these protests, local politics also serve to impact the political inclinations of the demonstrators, in turn creating space for coalition building and cross-pollination among the participating movements. The ‘Stop the Steal’ mobilizations have moved from grassroots-organized protests in places like Arizona towards more centrally organized and nationally orchestrated mobilizations with a dedicated political action committee, such as the ‘Million MAGA March’. With this national attention, a broader coalition of right-wing actors and ideologies have been mobilized and engaged in demonstrations, from militia groups and white nationalists to conspiracy theorists and internet trolls.

Conclusion

Pro-Trump and right-wing organizing has changed significantly since the election, and analysis of ACLED data indicates that it will likely continue to evolve going into the inauguration and initial stages of the Biden administration. Demonstrations have increasingly involved organized, armed militia groups. They have also involved armed, decentralized, and potentially violent individuals, especially those who may respond to ‘muster calls’ or travel from a distance to take action. And they have involved unarmed mass mobilization as well — all while sporadic attacks by sole perpetrators have become more common.

Right-wing groups and militias are already planning events on and around Inauguration Day, shifting in recent weeks from viewing the ‘Stop the Steal’ movement as the ultimate form of mobilization towards contesting the election with the assumption that the result cannot be changed before Biden takes office. The emergence of new groups and organizing parties indicates that militias and armed groups are not going away after the end of the election period. Given the resurgence of the modern militia movement in 2009, following the election and inauguration of former President Barack Obama, similar patterns are already beginning to replicate themselves — from militia recruitment to Tea Party-style political organizing.

Even as key trends in activity have changed, many of the same political strains that have impacted social movements, mobilization, and violence over the summer have persisted through the election and will continue into the near future. This includes the coronavirus crisis, which has worsened during the election and post-election period. Spikes in COVID-19 deaths have been highly correlated with demonstrations linked to the pandemic (for more, see this recent infographic from ACLED’s COVID-19 Disorder Tracker) — both those demanding a stronger government response to curb the pandemic, as well as those opposed to public health restrictions. With cases and deaths surging (Washington Post, 7 December 2020), officials are likely to take further steps to slow the spread of the virus, such as the renewed stay-at-home order put in place in California (The Guardian, 7 December 2020). In December, President-elect Biden stated that he will ask Americans to wear face masks for the first 100 days after he takes office (CNN, 3 December 2020). A more forceful government response to the pandemic, especially at the national level, could lead to a major increase in counter-mobilizing on the right.

The future of right-wing mobilization will also be impacted by changes in gun regulation. Many on the armed right are extremely worried about President-elect Biden or other newly elected Democrats implementing gun restrictions (CNN, 12 November 2020). Concerns are primarily focused on potential AR-15 or high-capacity magazine bans, both of which would likely drive major armed right-wing mobilization to state capitols and Washington, DC (CBS News, 12 November 2020; Vox, 20 August 2020). The risk of armed unrest around the gun regulation debate is likely to grow, as increasingly militant pro-Second Amendment organizations have continued to thrive throughout 2020 (Mother Jones, 2 December 2020).

Lastly, core drivers of left-wing mobilization — which is also a major motivator of reactive right-wing counter-mobilization — largely remain in place. From unmet promises for social and racial justice, to COVID-19’s massive economic impact, especially on marginalized communities, to persistent inequities in the healthcare system, the US has failed to meet many of the needs identified by these movements. The intersection of future spikes in left-wing protest activity and the right-wing mobilization patterns outlined above could constitute significant flashpoints for violence and unrest.

President Trump’s continued refusal to concede, support for disinformation campaigns aimed at delegitimizing the incoming administration, and reported preliminary planning to launch a 2024 bid to retake the White House on Inauguration Day (NBC News, 1 December 2020) — in addition to the potential for stronger public health restrictions, new gun regulations, and resurgent left-wing activism under President Biden — are among the range of drivers that could activate and shape the trajectories identified in this report. Monitoring these risk factors will be critical for efforts to prevent peaceful mobilization from devolving into political violence, and mitigating the threat of violent instability through the inauguration and beyond.