In late January 2020, an apparent United States drone strike targeted a car in Yakla, a mountainous area situated across Yemen’s Al Bayda and Marib governorates. Inside the car were Qasim Al Raymi and Abu Al Baraa Al Ibbi, the emir and a senior jurist, respectively, of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), the local branch of al-Qaeda’s global franchise (Al Masdar, 2 February 2020). A veteran jihadist militant from the Afghanistan wars and one of AQAP’s founders in 2009, Al Raymi became emir in June 2015 after another US drone strike had killed his predecessor, Nasir Al Wuhayshi, in Mukalla. Less than a month after Al Raymi’s death, AQAP announced Khalid Batarfi as the new emir. Also known by his nom de guerre Abu Al Miqdad Al Kindi, Batarfi is a Saudi-born Yemeni militant who rose through the ranks of AQAP as a prominent and charismatic ideologue (The National, 23 February 2020).

Al Raymi’s death has marked a turning point in AQAP’s decade-long history. Al Raymi oversaw AQAP’s expansion in southern Yemen, where the group held the third biggest port city in the country, and its eventual retreat into the mountains of central Yemen. Within the Islamist camp, AQAP also faced fierce competition at the hands of the Islamic State in Yemen (ISY), which escalated into months of fighting between the two groups between July 2018 and February 2020. Batarfi’s appointment came at a moment when AQAP was suffering from fragmentation and low morale, two factors that negatively affected its operational and mobilization capabilities (Al Araby, 22 March 2020). Today, AQAP appears to be in a transitional phase, as it redirects its weakened military force towards fighting against the Houthis.

Drawing on recently updated ACLED data, this report examines AQAP’s activity in Yemen from 2015 to the present.1We thank Yemen analyst Joshua Koontz (@JoshuaKoontz__) for his work geolocating AQAP activity via open-source intelligence and publishing the results on Twitter, which in turn facilitated ACLED’s granular recording of location data. In assessing the organization’s geographic outreach and its relations to other armed actors, the report identifies three phases of AQAP’s wartime activity: AQAP’s expansion (2015-2016), its redeployment and infighting with ISY (2017-2019), and the current retrenchment in Al Bayda (2019-2020). The report shows that following its territorial expansion in 2015-2016, AQAP has suffered major setbacks that have hampered its operational capabilities. The group currently operates in isolated pockets of territory along with a variety of anti-Houthi forces, a context that has forced AQAP to adapt its strategy amid a changing situation. Yet, AQAP has not been fatally defeated, and may take advantage of anti-Houthi sentiments to boost its insurgency yet again.

Expansion (2015-2016)

AQAP was formed in 2009 from the merger of the Saudi and Yemeni branches of al-Qaeda. Al-Qaeda affiliates in Yemen were responsible for the USS Cole bombing in 2000, and for several deadly attacks targeting foreign tourists as well as security and energy interests. Despite a Yemeni government crackdown on jihadist organizations inspired by the Bush administration, al-Qaeda staged a comeback in 2006 following a prison escape allegedly facilitated by elements of the Ali Abdullah Saleh regime (Johnsen, 5 March 2020). Among those who escaped were future AQAP leaders Nasir Al Wuhayshi and Qasim Al Raymi. AQAP gained notoriety among intelligence communities worldwide after claiming responsibility for the attempted bombing of Northwest Airlines Flight 253 on Christmas Day 2009 (UN Security Council, 19 January 2010). The group, however, thrived on the political instability that followed the 2011 Yemeni uprising. Operating under the semi-political mantle of Ansar Al Sharia, AQAP took advantage of the fragmentation that tore apart the Yemeni army to take control of several towns in southern Yemen, where it declared small Islamic emirates between 2011 and 2012 (International Crisis Group, 2 February 2017). These included Zinjibar, the capital of Abyan governorate, which fell under AQAP’s control with little or no resistance from the security forces.

In 2015, the outbreak of the war gave yet another boost to AQAP’s fortunes in Yemen. Amidst the fragmentation of the Yemeni armed forces, the Hadi government and the Saudi-led coalition saw AQAP as an indispensable bulwark to prevent Houthi-Saleh forces from advancing into central and southern Yemen. In fact, AQAP fighters actively cooperated with other anti-Houthi forces, agreeing to end confrontations with the government and joining “popular resistance” fronts that were formed in Abyan, Aden, Al Dali, Lahij, Shabwah and Taizz (Cigar, June 2018: 15). Nowhere was AQAP’s participation in the conflict more pronounced than in the mountains of Al Bayda, where the group mounted a fierce resistance against the Houthis from as early as 2014. The Houthis moved into Al Bayda in the last quarter of 2014 under the pretext of fighting ISY, and within one year took control of the province.

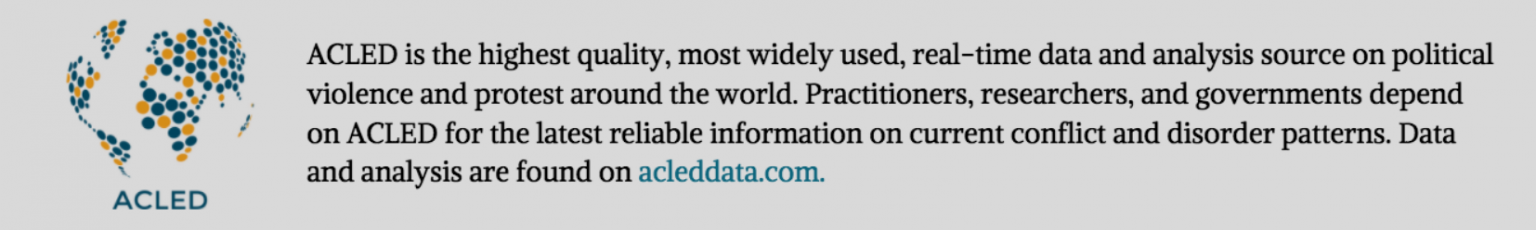

Since 2015, AQAP’s activity has largely concentrated in the southeast and northwest of the governorate (see Figure 1). In the southeast, the group’s training camps, situated in the districts bordering Abyan and Shabwah governorates, have been the target of several US drone strikes. Clashes with Houthi forces have clustered in Dhi Naim and Az Zahir districts, and in the northwestern region of Qayfa, a tribal area comprising Wald Rabi’, Al Quraishyah, and Rada’ districts. Qayfa is also home to ISY, and became the hotbed of the infighting between the two jihadist groups in 2018-2019.

While the Hadi government and the Saudi-led coalition were preoccupied with the advance of Houthi-Saleh forces in central and southern Yemen, AQAP took advantage of the situation to capture Mukalla, the capital of Hadramawt governorate and Yemen’s fifth largest city. Upon entering Mukalla almost without a fight on 2 April 2015, the group staged a mass jailbreak which freed 150 fighters – including the current AQAP emir Batarfi – from the central prison, looted approximately 100 million USD from the local branch of the Central Bank, and seized military equipment (Radman, 17 April 2019). During its year-long occupation of the city, AQAP developed governance practices that turned its Islamic emirate into a proto-state. Through its surrogate group Abna Hadramawt (“Sons of Hadramawt”), AQAP activated dispute resolution mechanisms, abolished taxes for local residents, promoted infrastructure projects, and organized festivals to bolster its support among the population (Kendall, July 2018: 8). Until April 2016, when an Emirati-led offensive drove AQAP out of Mukalla, the group collected an estimated two million USD every day in customs fees levied on goods and fuel entering the port.

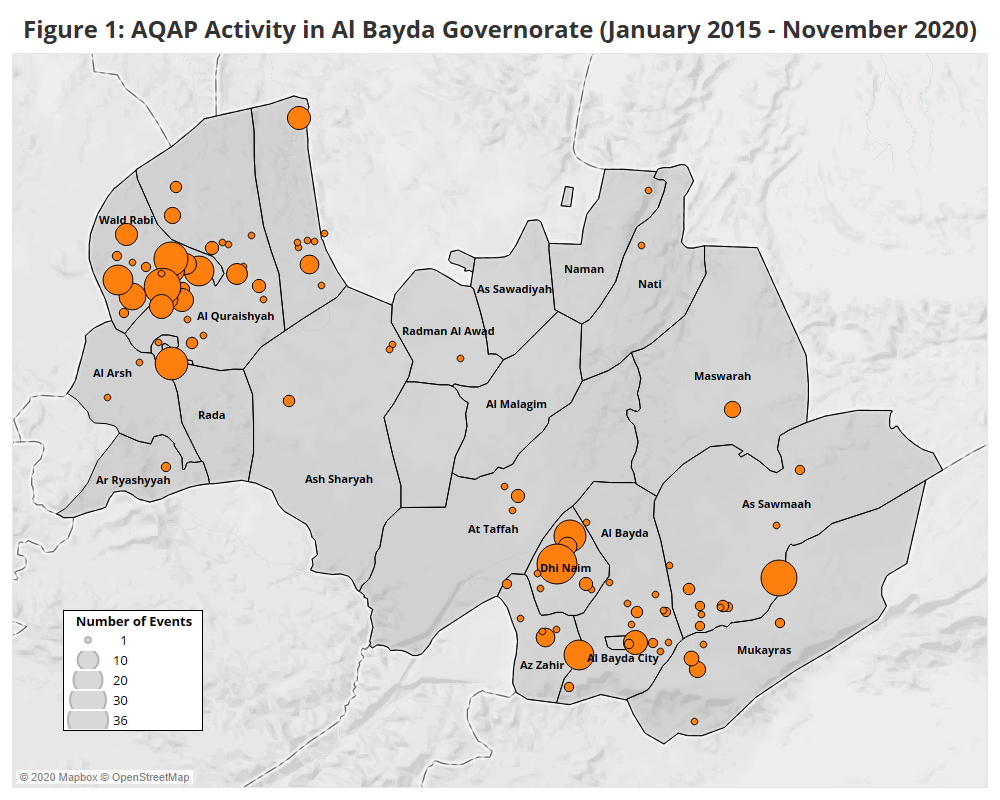

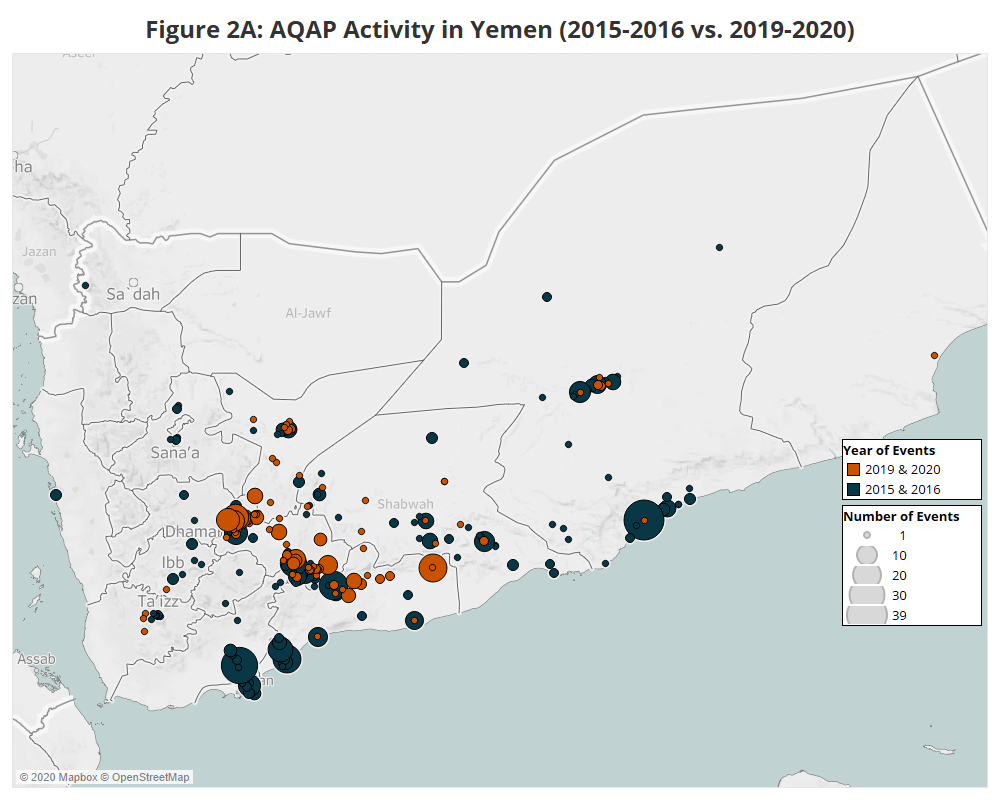

The inclusion of AQAP fighters in anti-Houthi popular fronts, along with the financial resources and military equipment acquired during the occupation of Mukalla, greatly contributed to the group’s expanding activity (Bayoumy, Browning and Ghobari, 8 April 2016). At its apogee in 2015-2016, AQAP was reported to be active in 82 of Yemen’s 333 districts. Four years later, the number has decreased to 40 (see Figure 2A and 2B). AQAP established a strong presence in Aden, taking advantage of its leading role in expelling Houthi-Saleh forces from the city’s northern directorates of Mansura and Sheikh Othman. Until a counterterrorism campaign coordinated by the United Arab Emirates (UAE) rooted AQAP out of Aden, the group carried out a string of assassination attempts targeting government officials which plunged Aden into a state of chronic instability (Salisbury, March 2018). In Mukalla, despite claims that it suffered a resounding defeat at the hands of a coalition-backed tribal alliance in April 2016, AQAP was allowed to transfer its forces out of the city and relocate to Shabwah and Abyan (Horton, 14 October 2016).

At the heart of AQAP’s success in 2015-2016 was its pragmatism. Contrary to the uncompromising sectarian narrative of ISY, AQAP has calibrated its message to local audiences, winning the support of local tribes who were largely concerned with protecting their homeland from the Houthis. AQAP shied away from imposing sharia laws or hastily creating a self-styled Islamic State, which would likely face backlash from local communities. Instead, it capitalized on widespread resentment over government neglect and Houthi oppression, while nurturing kinship and economic ties with the tribes (Radman, 17 April 2019). There is no doubt that tribal notables have occasionally coordinated with AQAP, nor that some areas were more receptive to its sectarian message. However, tribes have long been wary of AQAP, fearing that the group’s presence in tribal territory would elicit counterterrorism operations and further disrupt tribal orders (Al-Dawsari, June 2018).2 As early as 2012, local tribes resisted AQAP’s attempt to take control of the town of Radaa in Al Bayda (Mareb Press, 20 January 2012). The history of the Al Dhahab clan – a leading tribe from Qayfa, some of whose members have been associated with AQAP – reveals how ideology drives the preferences of tribes less than personal rivalries, internal succession disputes, and survival concerns (Van Veen, 29 January 2014; Abaad Studies, 10 October 2020).

Redeployment and Infighting with ISY (2017-2019)

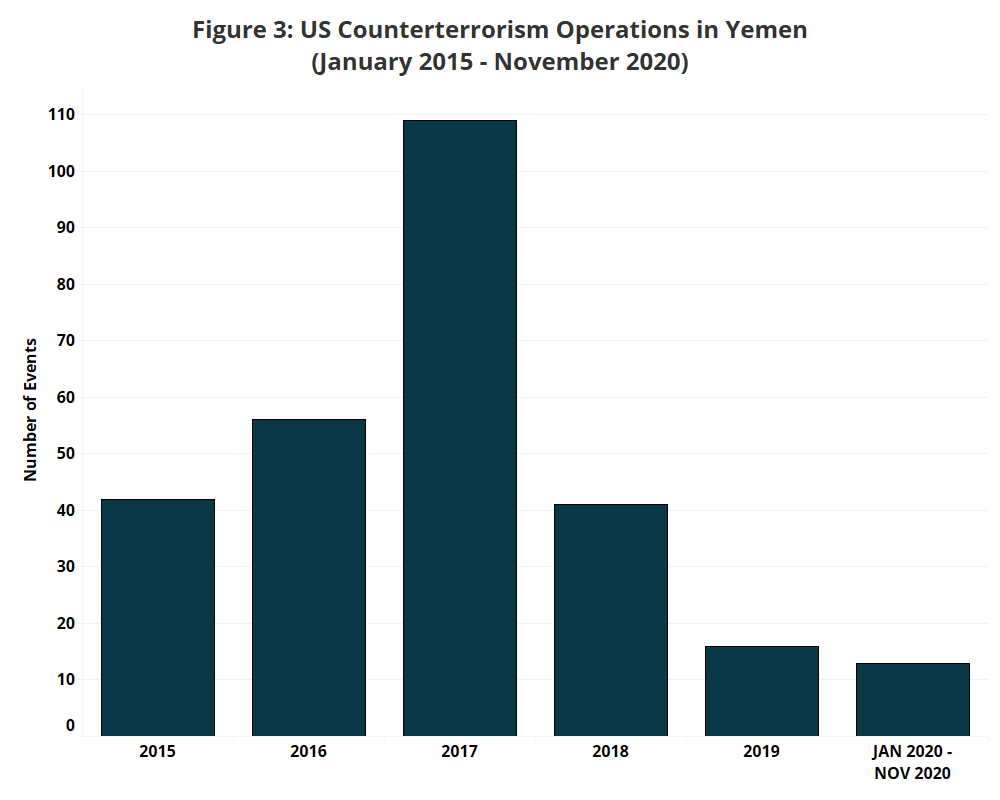

For over 12 months after leaving Mukalla, AQAP remained capable of carrying out deadly attacks against security forces and holding territory. Yet, following their sweeping successes in 2015-2016, AQAP suffered major setbacks that forced the group into redeploying its forces. At least four sets of factors explain AQAP’s crisis. First, the inauguration of the Trump administration coincided with a dramatic increase in the number of air and ground operations authorized by the United States (New York Times, 12 March 2017). Upon declaring the provinces of Abyan, Al Bayda, and Shabwah “areas of active hostilities,” an unprecedented series of air and drone strikes targeted positions assumed to belong to AQAP in March 2017 (see Figure 3). Though aligned with nearly a decade of counterterrorism operations conducted on Yemeni soil, the military-heavy approach endorsed by the Trump administration inflicted several losses to AQAP and ISY, while also exacting a heavy civilian toll. In January 2017, a botched Special Operations raid in Yakla area targeting AQAP emir Qasim Al Raymi killed instead several members of the Al Dhahab clan, including a pro-government tribesman whom the US mistakenly believed to be an AQAP operative (Al-Muslimi, 26 June 2019). It was estimated that at least 25 civilians, including women and children, have died in US ground raids launched between January and May 2017 (The Bureau of Investigative Journalism, 9 February 2017; The Intercept, 28 May 2017).

A third factor concerns the arrest and sanctioning of individuals with alleged ties to AQAP and ISY. International sanctions introduced in 2017 targeted Adil Al Dhubhani aka “Abu Al Abbas,” a UAE-backed Salafi militia leader from Taizz, Nayif Salim Salih Al Qaysi, a tribal notable from Al Bayda who served as governor from December 2015 to July 2017, as well as Sheikh Hashim Al Hamid and the Marib governor’s brother, Khalid Al Aradah (US Department of Treasury, 19 May 2017; 25 October 2017). Abdulwahhab Al Humayqani, an advisor to President Hadi who hails from a pro-government tribe in Al Bayda, has likewise been subject to sanctions by the US Department of the Treasury since 2013. The designation of political, tribal, and militia figures as “terrorists” was not without contestation (Washington Post, 16 February 2014; Yemen Shabab, 20 May 2017; Washington Post, 29 December 2018). In fact, it highlights the “amorphous” societal nature of AQAP, an organization in which affiliation is defined “by degrees and circumstances, rather than official status” (Baron and Al-Muslimi, 27 March 2017). Yet, sanctions have likely hampered the group’s infrastructure, as testified to by reports highlighting the increasing involvement of AQAP militants in smuggling networks and organized crime (Kendall, July 2018: 17).

Finally, the heightened pressure on AQAP has weakened the organization’s ability to maintain its internal cohesion. Drone strikes and ground operations have decimated AQAP, forcing its leadership into hiding and cutting communications. Falling short of new recruits and suffering from weak leadership, AQAP turned its public messaging against internal spies (Kendall, 14 February 2020). In Taizz, a string of disloyal elements accused of factionalism were disowned and expelled (UN Panel of Experts, 26 January 2018: 23). The main beneficiaries of AQAP’s fragmentation were Salafist militias variously aligned with the Hadi government or the Southern Transitional Council (STC), as well as ISY which aggressively boasted about its ideological purity.

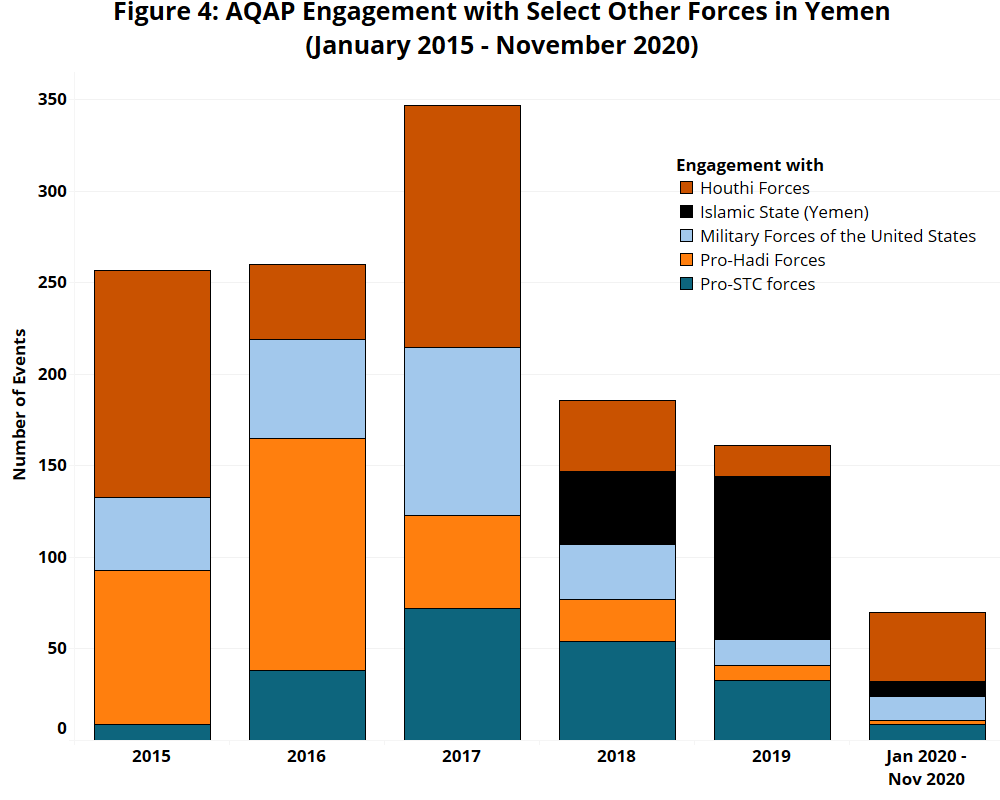

The four factors plunging AQAP into a major crisis coincided with the evolution of the jihadi “cold war” with ISY into a hot war in July 2018 (Hamming, 7 November 2018), which lasted until February 2020. In 2019, during the hottest phase of the jihadi infighting, more than 50% of AQAP activities targeted ISY (see Figure 4), and resulted in the killing of at least a hundred fighters. Local and national factors likely ignited the armed confrontations between the two groups, rather than ideological disputes on a transnational scale (Hamming, 7 November 2018).3French journalist Wassim Nasr finds that the killing of mediators Nabil Al Dhahab and Mamum Haten in 2014 and 2015, respectively, contributed significantly to widening the AQAP-ISY rift, although it is not clear why it took three more years for the infighting to break out (Nasr, 7 November 2018). The focus of AQAP on routing ISY from Qayfa began from mid-2018 onwards, at a moment of AQAP’s dwindling activity and structural weakness. Decimated by drone strikes and counterterrorism operations in Abyan, Marib, and Shabwah governorates, AQAP redeployed into Al Bayda, where it had a long-established presence. This shift, however, led AQAP to clash with ISY, its primary ideological competitor and strategic enemy (Perkins, 21 September 2018; Washington Post, 14 April 2019). As long as ISY is strong enough, its presence will increase the vulnerability of AQAP. There are several reasons for this. First, group cohesion is more difficult to enforce when a second group is continuously trying to undermine it. Second, a strategic competitor decreases the stability of AQAP’s local embeddedness with local tribes. Third, an increased number of interactions, even if non-violent, increases their activity on the radar of other declared enemies such as the US, and exacerbates the vulnerability of AQAP towards drone strikes.

Retrenchment (2019-2020)

After the jihadi cold war turned violent in July 2018, the jihadi infighting subsequently cooled off again in February 2020. As of November 2020, no clashes between AQAP and ISY have been reported in the last nine months as AQAP started its shift from redeployment to retrenchment. As shown in Figure 4, overall AQAP activity since January 2020 has also slumped.

This is due to a variety of reasons. First, as noted, a US airstrike killed then AQAP emir Qasim Al Raymi in January 2020 and led to the destruction of organizational capabilities. Second, a Houthi offensive in the Qayfa tribal areas this year led to a significant defeat of both AQAP and ISY at the hands of Houthi forces (Kendall, 25 August 2020). This necessitated a re-grouping. Third, AQAP’s media manager was reportedly killed by US drone strikes in May 2020 (Kendall, 23 June 2020). This might have resulted in an incapacity to publish claims for attacks, evidenced by the fact that recent attack claims lack the standard elements of past claims (Kendall, 16 November 2020). The most recent attack claim in November was published via text on Telegram and does not yet contain visual evidence of the claim.

Instead of fighting ISY, AQAP has ramped up its anti-Houthi rhetoric, in an attempt to reclaim its role as the main enemy of the Houthis. This is not a new AQAP strategy. It actively pursued such a strategy as early as 2014 in Al Bayda when the Houthis started to penetrate the province.4 In 2015, ISY attempted to pursue a similar strategy through media messaging, evidenced i.a. by the contents of the video “Soldiers of the Caliphate” (Hamming, 7 November 2018). For example, a recent video published by the AQAP media arm in November 2020 shows former Houthi prisoners from different areas of Yemen who seem to have been severely affected by their time in prison. Moreover, contrary to the phase of jihadi infighting with ISY between July 2018 and February 2020, attacks in recent months now primarily target Houthi forces. Almost 50% of AQAP interactions in 2020 are with Houthi forces (see Figure 4).

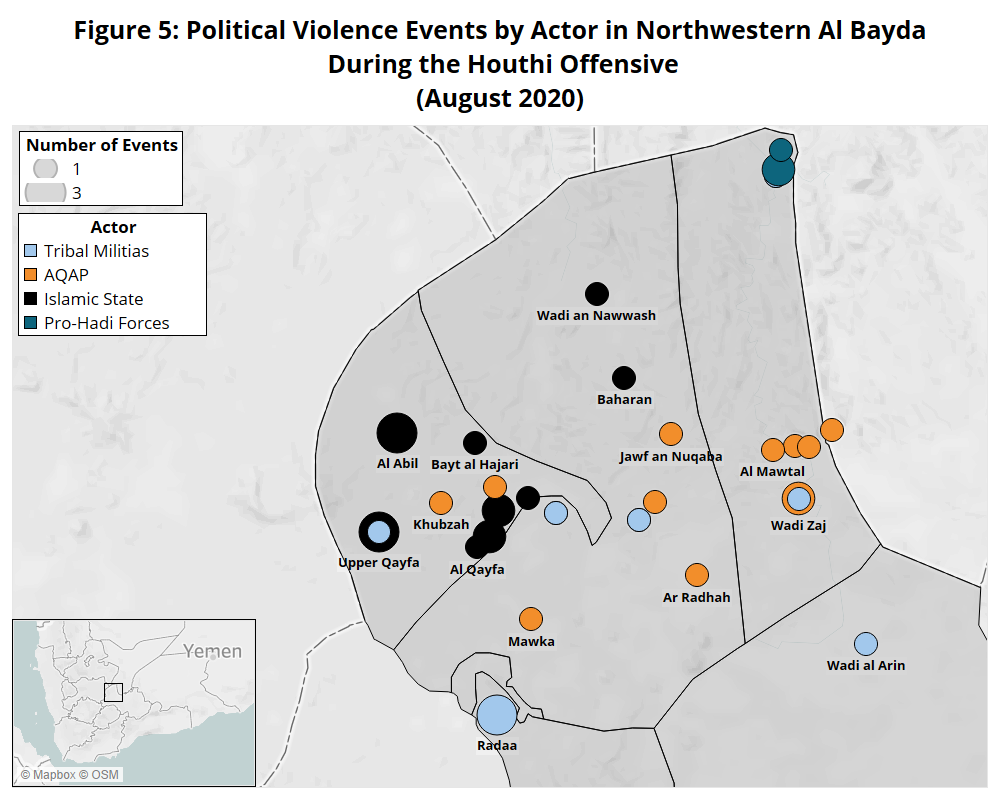

Although hostile ISY rhetoric towards AQAP persists (Kendall, June 19 2020; Kendall, 12 May 2020; Kendall, 29 April 2020; Koontz, 22 August 2020), violent confrontations between the two groups are rare. Some reports even allege the implicit cooperation of AQAP and ISY in fighting Houthi forces alongside Al Bayda tribesmen in August 2020 (Al Nasi, 9 August 2020; Mareb Press 9 August 2020; The National, 28 June 2018). These loose alliances are reminiscent of the popular fronts that emerged in Al Bayda in the wake of the 2014 Houthi offensive (Al-Dawsari, 11 January 2018). Figure 5 illustrates the overlap between areas of operations of anti-Houthi actors during the Houthi offensive in August 2020, indicating that these forces might have cooperated on informal terms against a common enemy. Yet, the Houthis have retained the upper hand in the battles and succeeded in ousting AQAP elements from several areas in Qayfa. The Houthi offensive has heavily weakened AQAP in northwestern Al Bayda, with no events attributed to the group in this area since September 2020. AQAP cells instead continue to operate in the southeastern parts of Al Bayda, where the group has since claimed over 10 attacks.

The Houthi assault on Al Bayda is likely a contributing factor in AQAP’s strategic shift from fighting ISY to spearheading the anti-Houthi front in Al Bayda (Al-Madhaji, 4 June 2020). Several tribal areas that had until recently remained largely neutral amidst the civil war were taken over by the Houthis in recent months. Among these events is the failed Awadh tribal revolt, which culminated in violence after months of simmering tensions between local tribesmen and the Houthis. Houthi forces crushed the rebellion and, by June, completely took over Awadh territory (Al-Dawsari, 22 June 2020). AQAP has long taken advantage of tribal grievances towards the Houthis by positioning itself at the epicenter of Houthi opposition in Al Bayda, and therefore presenting itself as a potential partner for tribal resistance movements. Indeed, elements of the Suraymah tribe seem to validate this hypothesis as there are some tribe members fighting with the government while others are with AQAP, including the AQAP emir of Qurayshiah (Yemen News Portal, 12 August 2020; Debriefer, 17 August 2020). According to Abaad, the Suraymah tribe has taken over leading the Qayfa tribes since the Al Dhahab were decimated by airstrikes and vendettas (Abaad, 10 October 2020). Unsurprisingly, the current role of the Suraymah tribe is reminiscent of the role of the Al Dhahab clan in Al Bayda.

As noted above, the strategy of installing itself at the helm of a “common anti-Houthi front” replicates what AQAP successfully did to counter Houthi advances in 2014-2015. As Bayda tribes fear occupation from the Houthi forces, AQAP steps in as a temporary partner for the tribes. AQAP is then able to develop strong capabilities, and, in turn, take over significant territories in Yemen. What might be different in 2020 from 2014 is the more consolidated role of the pro-STC forces, as well as UAE-supported counterterrorism forces in Shabwah and Hadramawt, which seems to pre-empt a flawless take over of territories.

The designation of Khalid Batarfi, a Saudi national anchored in Yemen for years, as successor to Al Raymi, an Afghan war veteran, is another potential factor for the re-orientation of “declared enemies.” The choice of Batarfi was not straightforward, as other candidates had similar credentials. Batarfi, however, could boast a unique profile, including local links due to his Hadhrami roots and marriage to a Yemeni woman (Johnsen, 22 March 2020). He likewise had a religious reputation as a strong and charismatic AQAP ideologue, and had a veteran role in the organization (The National, 23 February 2020).

Altogether, 2020 has been a year of retrenchment for AQAP. Today, AQAP is less active than in previous years. Despite a recent uptick in activity between August and October 2020, which could indicate a slow consolidation of capabilities following the drone strike that killed both its Emir Al Raymi and senior jurist Al Ibbi in January, AQAP’s activity plummeted in November.

It is yet to be seen how the group can mingle with elements in Al Bayda’s tribal society, which depends on the ideological and strategic choices of tribes towards the Houthis. Grievances have certainly increased after formerly neutral tribal territories have been taken over by the Houthis. A certain kind of opportunity window, however, could be exploited by the militant jihadi group. What is more, if AQAP manages to re-consolidate itself in Yemen, the threat it poses towards its ‘distant’ enemies, such as the United States, could increase as well. This is the driving force behind the US attempts to contain AQAP in Yemen (CNN, 8 April 2015).

Conclusion

This report has categorized the evolution and devolution of AQAP into three different phases: expansion (2015-2017), redeployment (2017-2019), and retrenchment (2019-2020). Drawing on ACLED data, it has shown how AQAP expanded in the first two years of the civil war and how it exploited the initial fragmentation of the security landscape in Yemen. The report has then illustrated how AQAP was weakened by an extensive campaign of US drone-strikes, coalition campaigns (i.e. the build-up of ‘local’ counter-terrorism forces), and a heavy phase of infighting with ISY. This phase, the ‘phase of redeployment’ from different parts of Yemen towards Al Bayda, lasted from 2017-2019. Finally, as a result of the jihadi infighting and the killing of AQAP Emir Qasim Al Raymi, this report has shown the last phase of AQAP’s retrenchment in Al Bayda in 2019-2020, along with the steady rebuilding of capabilities, tribal embeddedness, and group cohesion. It remains to be seen whether AQAP will manage to capitalize on the many security vacuums in Yemen, and if it can herald a new phase of expansion by replicating its 2014 strategy of taking advantage of tribal grievances to install itself at the helm of a common “anti-Houthi front” in Al Bayda’s tribal areas.