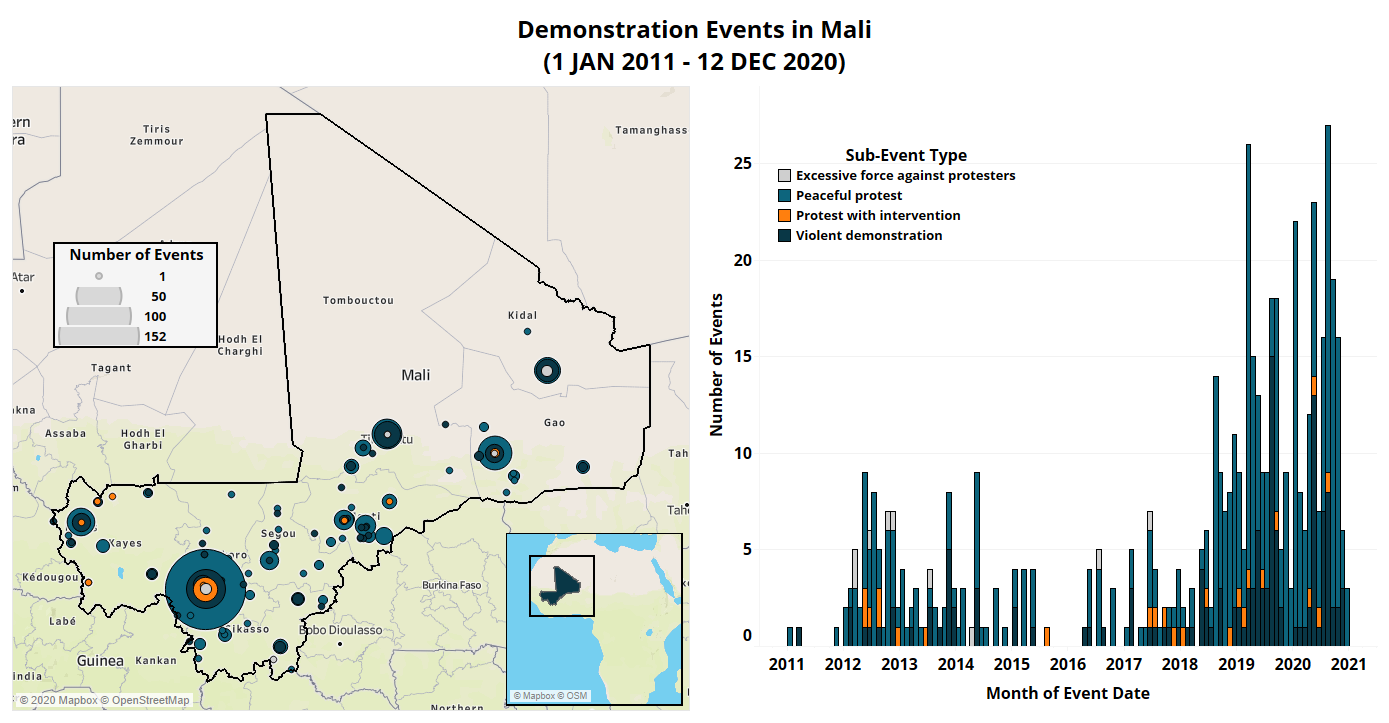

Thus far, 2020 has been the deadliest year on record in Mali. A downward spiraling trend has been observed since 2016, following the spread of violence to central Mali amid the emergence of Katiba Macina. In 2017, Katiba Macina was subsumed by the creation of the Al Qaeda-affiliated Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM), which gathered several militant factions into a Sahelian jihadi conglomerate. The rise of JNIM was accompanied by the coming to prominence of the rival Dogon-majority militia Dana Ambassagou, and jihadi competitor Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS). These developments led to an escalation in multi-directional violence through armed attacks, scaled-up military operations, and increased targeting of civilians. A military coup in August 2020 broke the prevailing and seemingly untenable status quo, and has provided opportunities to change the country’s downward trajectory as Malian politics are reshaped. However, Mali’s transitional government faces an uphill battle to build consensus and reign in the violence. As it stands, Mali remains at a crossroads of hope and uncertainty.

On 18 August 2020, Mali’s crisis took a dramatic turn when a group of mutinous senior officers based in the garrison town of Kati ousted former President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta (commonly referred to by his initials IBK) in a coup d’état. The coup numbered the fourth since Mali’s independence, coups which have been dovetailed by as many Tuareg-led rebellions. Parallels were quickly drawn to the military coup in 2012 that removed IBK’s predecessor, Amadou Toumani Touré, from power. The 2012 collapse of the Malian state paved the way for jihadi militants — piggybacking on a Tuareg rebellion — to take over the country’s north. The French military intervention in 2013 ousted the militants, who then diffused across the subregion.

However, the present context differs considerably from that in 2012. Mali currently hosts the intersecting missions of UN peacekeeping, EU capacity building to train local security forces, the French-led counterterrorism effort (Operation Barkhane), and the regional G5 Sahel Force. Nevertheless, the presence of many international troops to stabilize the West African nation did not prevent a military coup, which came amid months of socio-political upheaval.

Unrest Boiling Over

The Movement of 5 June-Rally of Patriotic Forces (M5-RFP) was a self-proclaimed protest movement in the wake of a 5 June mass rally in Bamako, which channeled popular discontent over poor living conditions, corruption, widespread insecurity, and disputed election results (RFI, 2020). A coalition of religious leaders, opposition figures, and civil society, spearheaded by the influential imam Mahmoud Dicko, staged frequent mass demonstrations and called for civil disobedience to force IBK’s resignation. The health crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and countermeasures imposed by the government further exacerbated popular discontent. The abduction of opposition leader Soumail Cissé placed additional pressure on the regime. Controversial elections held in March and April during the pandemic amid rampant violence were subsequently disputed when the constitutional court overturned the results in favor of IBK’s ruling party, Rally for Mali (RPM). All this sharpened public discontent (ECFR, 2020).

IBK’s entourage was involved in numerous corruption scandals during the years of his reign (Bamada, 2020). IBK was repeatedly accused of nepotism after he put family members in key positions (Sahelblog, 2020). Demonstrators saw his administration as the embodiment of ineptitude and abuse of power. In part, the coup represents a response to the refusal of a regime — incapable of managing a protracted and escalating crisis — to step down (aBamako, 2020). The IBK regime either underestimated people’s grievances or remained disoriented, with responses ranging from neglect to the use of force.

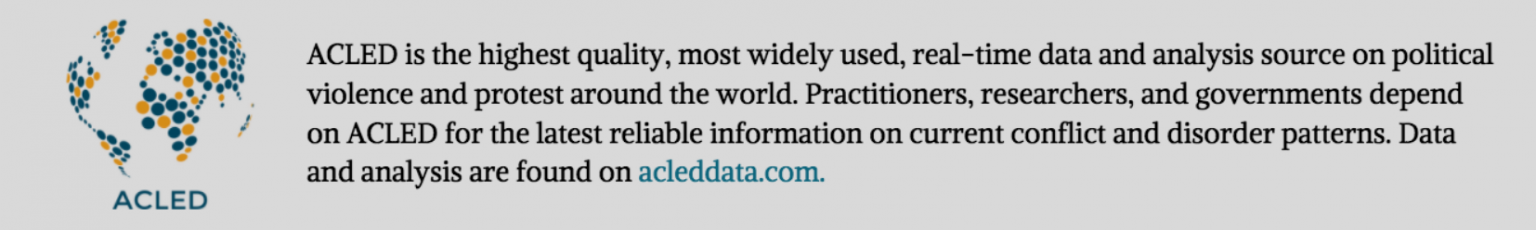

Mali’s public discontent fits into a larger nationwide civil unrest pattern for the past four years (see figure below). This unrest results from a range of socio-economic and socio-political issues primarily concentrated in the capital of Bamako and the peripheral cities of Kayes, Tombouctou, Gao, and Kidal. Demonstrations in Bamako and Kayes have centered around more general popular grievances: poor infrastructure, road degradation along major transit routes surrounding the capital, the dysfunction of key public services — most notably the health and education sectors, and poor working and living conditions. In Gao and Timbuktu, local security issues related to banditry and militancy have been at the forefront of unrest, often escalating into violent demonstrations and vigilante and intercommunal violence, usually with an ethnic dimension. In Kidal, the presence of international forces has frequently sparked demonstrations. A recent episode in late October and early November came in reaction to statements by French President Emmanuel Macron regarding the publication of caricatures of Prophet Muhammad (Menastream, 2020).

In this context, Mali’s main jihadi militant coalition, JNIM, has, together with other Al Qaeda-affiliated groups across the globe, coordinated a media campaign to incite demonstrations and attacks against France and Macron. At the national level, JNIM geared its official propaganda to exclusively portraying itself as an “expeller” of foreign forces, which it demonstrated on 30 November through simultaneous rocket attacks against military bases harboring international forces in the towns of Gao, Kidal, and Menaka (Ouest France, 2020; Twitter, 2020).

The Quest to Legitimize the Coup

Key stakeholders within the international community condemned the coup amid concerns that Mali would slide further into chaos. The military junta, monikered the National Committee for the Salvation of the People (CNSP), quickly articulated its willingness to maintain existing agreements and cooperate with international forces in order to calm both international and national stakeholders (France 24, 2020).

While the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) imposed sanctions, other key actors’ statements were more ambiguous and appeared to balance between constitutional legality and the lack of legitimacy IBK enjoyed at the national level. Thus, these statements reflected an understanding that it was unrealistic to demand the IBK regime’s return, as it was now considered illegitimate. It was from the perceived illegitimacy of the former regime that the coup-makers claimed to have drawn their popular legitimacy (Jeune Afrique, 2020). Calls for elections and a quick return to constitutional order were seen as recycling impractical recipes, serving short-term fixes for often deep-seated structural issues (OrientXXI, 2020). Often described as a model of democracy in a volatile region (The Broker Online, 2014), Mali’s presumed state of democracy has been increasingly disemboweled. Elections are regularly delayed and characterized by violence and contestation (Sipri, 2016). There are accusations of electoral fraud, and voter turnout remains in the bottom percentile by regional standards (IDEA database).

The Difficulty of Militarizing the Regime and Building Consensus

A transitional government was put in place in early October amid pressure from ECOWAS and talks with national parties to transfer power to civilians (France 24, 2020). However, the junta has clung onto power (ECFR, 2020) by giving its members key posts and asserting influence over the interim government’s composition (Le Point, 2020). The junta has taken further steps to militarize the administration by designating 13 out of 20 governor posts to military officers (DW, 2020), at a time when civilian administrators are on strike (Maliweb, 2020). The strike by civilian administrators was preceded by an October demonstration in which prefects and subprefects demanded the state provide them with protection and secure the release of their colleagues held in captivity by armed groups. Their ongoing captivity was viewed as an expression of neglect following the negotiated release of opposition leader Soumaila Cissé (Africa Radio, 2020). Unprecedentedly, the signatories of the 2015 Algiers Peace Agreement — the ex-rebel bloc, Coordination of Azawad Movements (CMA), and the pro-government militia coalition, Platform — received two ministerial portfolios each (l’Opinion, 2020). However, the M5 protest movement — which was instrumental in bringing down the IBK regime by exerting popular pressure and mobilizing support during the coup — felt relegated to the sideline without any direct representation in the new government (RFI, 2020). The National Transitional Council (CNT), the equivalent of a transitional parliament and legislative body until the next elections are held, was put in place as part of the transition roadmap (Anadolu Agency, 2020). The composition and process of putting together the assembly have been heavily criticized by the political class, civil society, and armed groups, due to the overrepresentation of the military, exclusion of some parties and armed groups, and allocation of seats (The Africa Report; DW; Maliweb, 2020).

Disunity Among Insurgents and Engaging a Controversial Key Armed Actor

Beyond appeasing a range of actors by distributing patronage resources and building consensus, the transitional government is facing profound challenges in steering the country on the right track. They continue to grapple with the legacy of a near-decade-long period of major instability which has continuously escalated over the past four years. The upswing in violence correlates with the emergence of JNIM, which plays a central role in the current unrest. JNIM accounts for an estimated 75% annual average of fatalities attributed to jihadi violence and nearly 30% of the overall fatalities resulting from organized political violence in 2017-2020. At the time of its creation, JNIM presented a politico-military-religious alternative, transcending ethnopolitical fault lines (Jihadology, 2017). In hindsight, the strategic value of the alliance formation showed that it significantly increased and widened the geographic scope of violent activities when compared to its constituent groups combined (African Affairs, 2020).

Two factors play to the advantage of the junta: first, the coup came during the rainy season and hence during a period characterized by a temporary decline in violence following the patterns of preceding years. Nonetheless, the relative calm (see figure below) should not be interpreted as directly related to the coup per se.

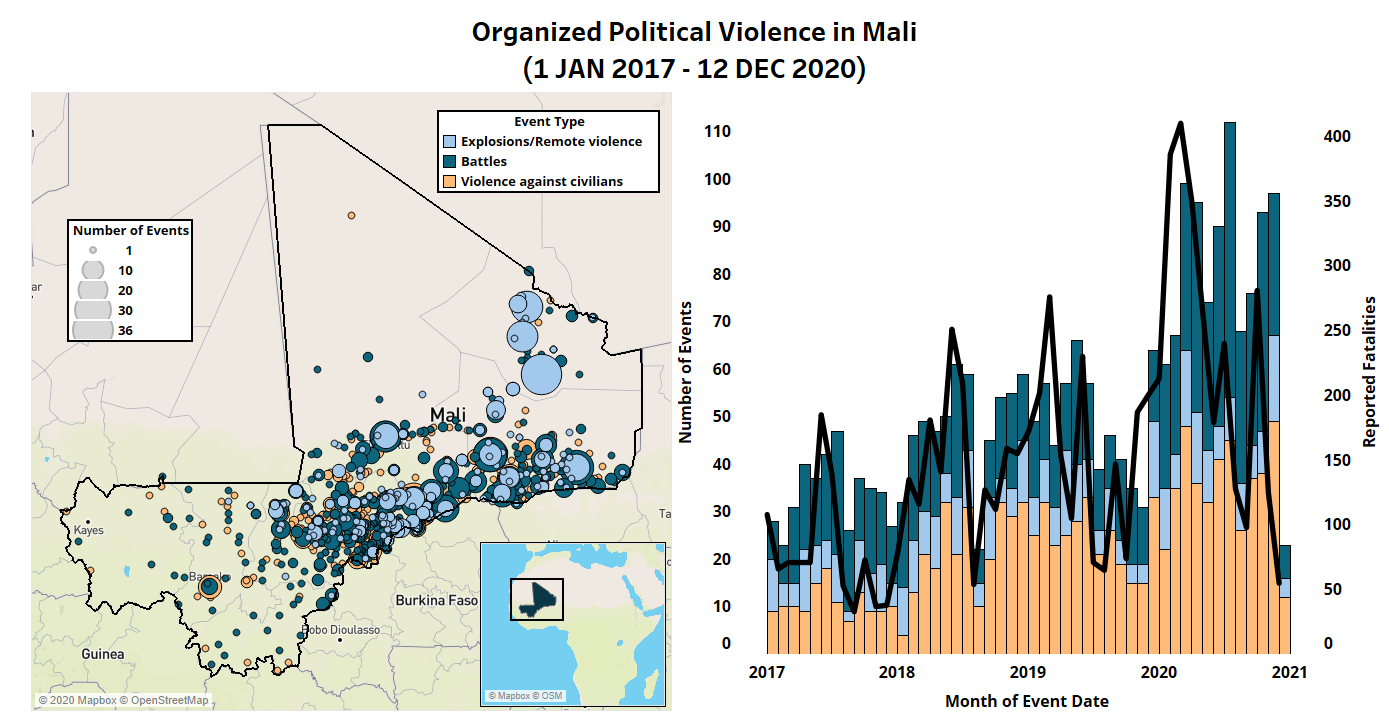

Second, disunity within the insurgency — including the descent into open warfare between JNIM and ISGS — has temporarily weakened it. Hence, jihadi militants are currently contesting influence and territory between themselves rather than the states they have declared their enemies. Fighting between the organizations concentrated in the Inner Niger Delta and the Malian side of the “tri-state border” region has led to an estimated 415 fatalities this year (see figure below), which accounts for a significant portion of the increase in deaths recorded so far in 2020. One of the key divergences between the two jihadi franchises is JNIM’s openness to negotiate with the Malian government (CTC Sentinel, 2020).

When the junta came to power, a pre-existing effort to secure the release of Malian opposition leader Soumaila Cissé was seemingly fast-tracked. Cissé was abducted in late March 2020 by presumed Katiba Macina militants, who are part of JNIM. He had been campaigning during elections in his home district of Niafunke in the Tombouctou Region. Cissé was held in captivity until early October when he, alongside three foreign hostages, were released in exchange for more than 200 suspected militants and ransom money reported to be at least 10 million Euros.

By securing the release of Cissé, the junta demonstrated that it could take action and deliver, albeit at a heavy price. The prisoner swap was perceived as a major victory on the part of JNIM and a boost to the group’s prestige at the social, military, and political level (Le Monde, 2020). Further, the deaths of several senior Algerian leaders of Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) may have provided the JNIM leader and long-serving Tuareg rebel commander, Iyad Ag Ghaly, more room to maneuver as well as local ownership of the insurgency to enact JNIM’s agenda. In the wake of the prisoner exchange, the African Unions’ Commissioner for Peace and Security, Smail Chargui (Le Temps, 2020), and the Secretary-General of the United Nations, Antonio Guterres, expressed openness to dialogue with jihadi militants in the Sahel (Le Monde, 2020).

This suggests a gain of political capital by JNIM amid the prisoner exchange given the timing of both Chargui’s and Guterres’ statements. Chargui’s and Guterres’ positions reflect an understanding of the need to engage key armed actors in dialogue to curb the violence, regardless of their ideological beliefs. Hence, the prisoner swap opened the possibility of a broader negotiation effort between the junta-led transitional government and JNIM, with the larger aim of achieving stability in the conflict-ridden country.

Despite the importance of dealing with armed non-state actors in the conflict, negotiations with jihadi militants remain controversial. This is evidenced by the different positions of Malian and French authorities (OrientXXI, 2020). French President Macron and Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian have publicly rejected talks with jihadi groups (Le Figaro; VOA Afrique, 2020). Contrarily, the Prime Minister of Mali’s transition government, Moctar Ouane, stated that it was the will of the Malian people to engage in dialogue (France 24, 2020). Nevertheless, the French discourse on the matter has cautiously evolved and become more nuanced. In a recent interview, the French chief of staff, General François Lecointre, mentioned the possibility of holding dialogues with the enemies of French and Malian forces, while emphasizing that the counterpart needs to be representative and legitimate (Africa Radio, 2020).

The intentions of groups such as JNIM are unclear, and the outcomes uncertain (ICG, 2019; War On the Rocks, 2020). Nevertheless, the all-security approach favored by national, regional, and international military actors in the Sahel has shown its limits and even dangers as reflected by the escalation in violence in recent years. Therefore, exploring such avenues is unlikely to worsen the crisis which reaches a new high-water mark each year.

A negotiation process would be fragile and could easily be disrupted by both internal and external influences. Such a process may involve escalation in violence as the parties make bids to advance their bargaining strength. Potential spoilers include excessive French military operations that may shatter any goodwill built up between JNIM and the Malian government. JNIM’s Islamic State counterpart, ISGS, has previously exploited internal JNIM dissent by poaching members, and could attract those who do not support dialogue with Malian authorities. Unrestrained and uncontrolled violence by government forces could also derail negotiation efforts, just like local outbursts of violence could escalate and complicate such engagements.

Hence, both the junta-led transitional government’s capacity to intervene and mediate as a neutral arbitrator while managing the military will be called into question. For instance, an embargo imposed and sustained by jihadi militants since early October on the village of Farabougou demonstrates such concerns as the Malian armed forces have not been able to lift the siege (RFI, 2020). Presumed Katiba Macina militants accuse Bambara Donsos of abuses against the Fulani community. They are now pursuing a punishment and subjugation campaign against Bambara farmers and Donsos in the Niono Cercle, similar to a protracted and still ongoing military campaign in “Dogon Country” against the Dogon-majority Dana Ambassagou militia and its perceived constituencies.

There is a high degree of uncertainty regarding what the future holds for Mali. If the military junta broke the prevailing status quo, a sober assessment is that the result of the coup will engender a return to the status quo ante (Sahel Blog, 2020). More optimistically, the transition provides a window to reshape Malian politics and reassess how to engage key armed actors and explore paths that positively impact conflict dynamics in order to achieve stability and give respite to communities affected by violence through a locally negotiated system of hybrid governance.