Six years after the coup that ousted President Abdrabbu Mansour Hadi and his government, the Houthi movement, otherwise known as Ansarallah, has strengthened its grip on northern Yemen. It currently rules over approximately 70% of the country’s population, and in 2020 mounted new military offensives in Al Jawf, Marib and Hodeidah. Domestically, the group has suppressed dissent and won complete control of what is left of the Yemeni state, appointing loyalists in civilian and military bodies and transferring powers from government institutions to a shadowy network of Houthi supervisors. A pervasive security apparatus, built on the ashes of Ali Abdullah Saleh-era intelligence bodies (UN Panel of Experts, 27 January 2020: 9), has focused on protecting the Houthi regime and monitoring the movements of suspected enemies, including humanitarian organizations. Among the successes boasted by Houthi officials is the restoration of security and stability in Houthi-controlled regions, which they contrast with the mayhem plaguing the areas under the authority of the internationally recognized government and allied coalition forces (Yemen Press Agency, 21 December 2019; Al Masirah, 21 July 2020; Ansarollah, 2 January 2021).

Yet despite these repressive efforts, tensions continue to rise in northern Yemen. From the failed uprising incited by former president and erstwhile Houthi ally Ali Abdullah Saleh to sporadic tribal rebellions and infighting within Houthi ranks, localized resistance to Houthi rule has turned violent in several provinces. Confronted with the outbreak of dissent, the Houthis have accused “foreign-armed forces” of terrorist activities, and have used violence to force internal opponents into submission. However, the roots of these incidents are largely domestic in nature. Not only do they highlight the unstable and violent nature of governance in Houthi-controlled territories, their occurrence also challenges the very essence of the wartime political order based on the acquiescence and collusion of societal groups with the Houthi-dominated state authorities (Staniland, 2012).

This report draws on ACLED data to examine patterns of infighting and repression in Houthi-controlled Yemen from 2015 to the present. It shows that behind the purported projection of unity in the face of the ‘aggression,’ local struggles within the Houthi movement, and between the movement and the tribes, are widespread across the territories under Houthi control. This geographic diffusion, however, has not translated into a unitary front against the Houthis; it rather reflects localized resistance to Houthi domination and encroachment in tribal areas which has stood little chance against the Houthis’ machine of repression.

Infighting

Despite their ostensible cohesion, the armed forces loyal to the Houthis consist of a heterogenous assortment of militants and professional soldiers. These forces are composed of approximately 200,000 troops, two thirds of which have been recruited since the start of the war according to a recent report (Al Masdar, 3 January 2021). Alongside the regular army, special military units and armed militias operate under the command of high-ranking Houthi officials, loyal tribal shaykhs, and other prominent figures capable of rallying support locally. While expected to show ideological commitment to the Houthi cause, local commanders also enjoy relative autonomy, operating as a network of militias that are involved in the extraction of levies and the recruitment of fighters in support of the war effort (Diwan, 25 November 2020).

This “cartel-like” structure (Shiban, 4 December 2020), however, is prone to stoking tensions within the movement. Rival factions are reported to exist among senior Houthi officials competing over access to positions of power and control of rents. While these are rarely — if ever — acknowledged in public, concerns over balancing their relative influence on decision-making are said to determine the allocation of regime posts and resources (Al Araby, 19 July 2019; Marib Press, 28 December 2019). Across Houthi-controlled territories, tensions have occasionally arisen between local Houthi ringleaders, derogatively known as mutahawwithin (ACAPS, 17 June 2020), and militia commanders hailing from Yemen’s northern governorates, the cradle of Ansarallah. Such hostilities have emerged in response to the latter’s encroachment in central Yemen at the expense of local Houthi elites who face increased marginalization in political and security institutions.

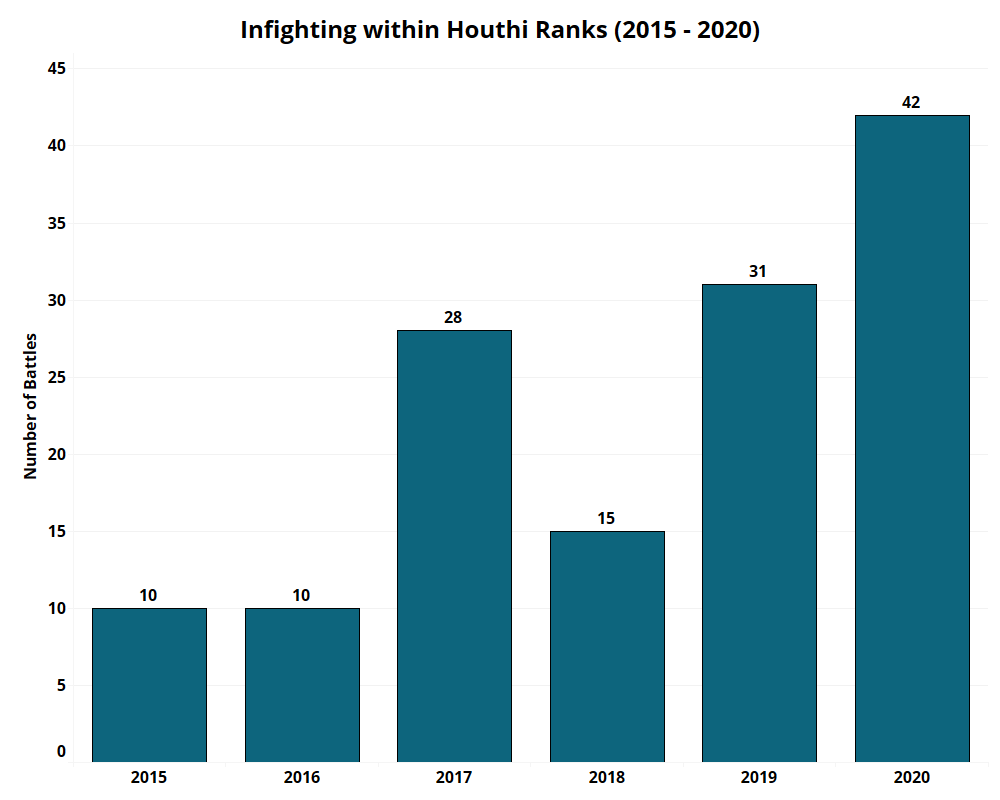

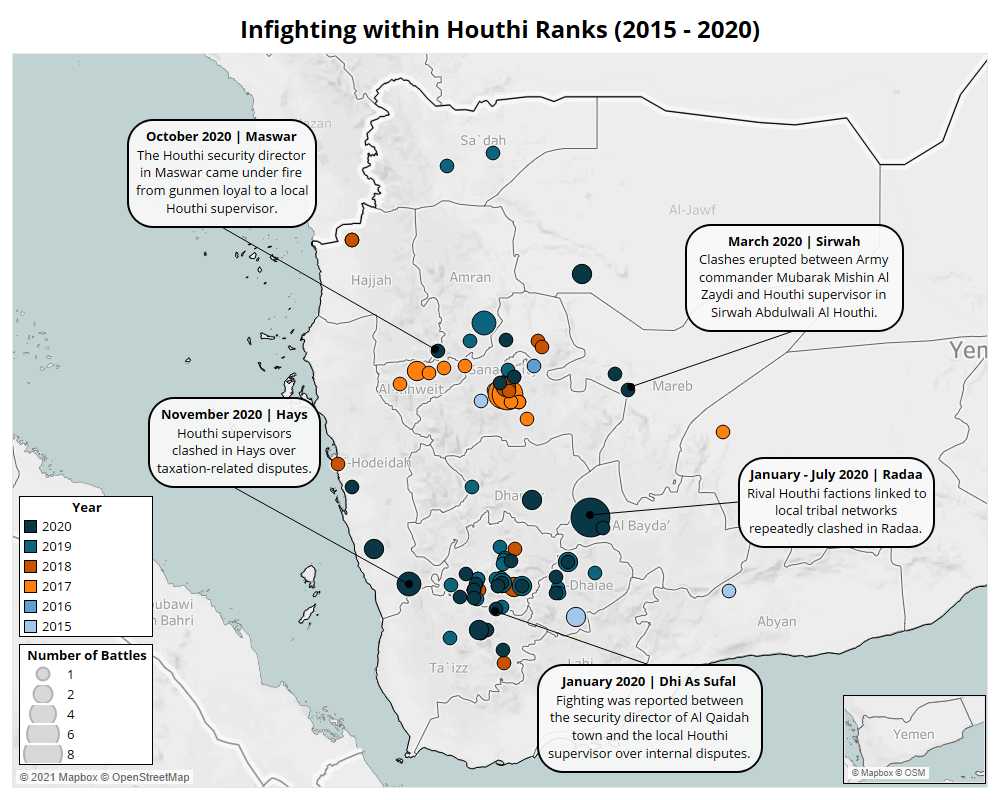

Data recorded by ACLED reveal that infighting within Houthi ranks reached a new peak in 2020 (see figure below). In 2020, more than 40 distinct battles between opposing Houthi forces were recorded in 11 governorates, compared to the 15 battles distributed across six governorates in 2018 and the 31 battles across seven governorates in 2019. Since 2015, confrontations have involved a wide range of actors within the Houthi camp, including regular army troops, Republican Guard soldiers loyal to Ali Abdullah Saleh and his nephew Tareq (who now leads the anti-Houthi forces on the western front), and local Houthi supervisors, or mushrifin. With the notable exception of events in December 2017 — when the spike in infighting was a direct result of the collapse of the Houthi-Saleh alliance — what has since been driving this internecine violence is a multitude of locally situated struggles among elements of the Houthi regime over land property, checkpoint control, and taxation.

Despite a relative decrease from the record high of 2019, Ibb remains the ‘hotbed of infighting’ in Houthi-controlled areas with nearly one fourth of the total events recorded by ACLED in 2020 (see figure below). Since 2017, tensions between the local security director Abdulhafiz As Suqqaf — a former ally of Saleh and an enabler of the Houthi advance in Ibb — and the loyalist Houthi faction from Saada escalated into heavy clashes, involving their allied tribal networks and plunging the governorate into instability (for more, see ACLED’s report on Houthi infighting in Ibb). In fact, these clashes are a testament to the local resentment existing among groups that had been acquiescent over, or had actively supported, the Houthi takeover across central and northern Yemen in 2014 and 2015, and were later disposed of by Houthi loyalists. More recently, sporadic outbursts of violence between rival Houthi factions continued through the first half of 2020, resulting in at least eight deaths between January and July.

Other governorates experienced a marked increase in internecine violence in 2020. In Al Bayda, the town of Radaa, which had fallen under the control of Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula in 2012 (Van Veen, 29 January 2014), was the site of several violent confrontations between rival Houthi factions linked to the local tribal networks of Riyam and Al Jawf Al Qayfa (Hafryat, 12 January 2020; Al Masdar, 19 July 2020). The conflict thus combines tribal grievances over land disputes and revenge killings with factional hostilities between Houthi ringleaders in Radaa. In Al Hodeidah, clashes broke out in the southern districts of Tuhayat and Hays over the distribution of levies among local Houthi leaders, pitting local mutahawwithin commanders from the Tihama plains both against Houthi supervisors from Amran and each other (Al Arabiya, 12 February 2020; Al Ayyam, 28 November 2020). Similar incidents were also reported north of Sanaa (Khabar Agency, 19 October 2020), in Taizz (Yemen Shabab, 28 March 2020), and in Marib — the latter being particularly notable due to the involvement of the Third Military Region commander Mubarak Mishin Al Zaydi (Al Mashhad Al Yemeni, 26 March 2020).

This disparate sequence of events across Houthi-controlled territories reflects the tensions running between the center and the periphery of the movement. In some territories, the centralization of power in the hands of an inner circle consisting of Houthi loyalists is facing opposition from local factions that risk losing authority. Occasionally, factional infighting has merged with communal disputes, leading local Houthi ringleaders to mobilize their respective tribal supporters (Al Mashhad Al Yemeni, 13 January 2020). Indeed, relationships between the Houthis and the tribes have grown increasingly strained in much of northern Yemen, with rising levels of tribal resistance and Houthi repression.

Tribal Disorder

Since 2015, tribes have spearheaded the military campaign against the Houthis in several battlefronts across Yemen, although intermittent or inadequate support from the armed forces of the Yemeni government and the Saudi-led coalition has been a frequent cause of frustration. Over the past year, the Murad tribe mounted a fierce resistance against the Houthi offensive in Marib amidst a spectacular failure of the army to coordinate and lead the fighting (Nagi, 29 September 2020). Likewise, tribal fighters and shaykhs have been enlisted to join brigades associated with the government and the coalition, such as the powerful Second Giants Brigade deployed on the western front and dominated by the Al Subayha tribe (Al Masdar, 3 January 2021). Beyond mere fighting, tribal mediation has also succeeded in achieving several prison swaps between the government and the Houthis, often outperforming UN-brokered mediation efforts (Al Masdar, 9 December 2019; Al Dawsari, 10 November 2020).

Inside Houthi-controlled territories, tribal coexistence with Ansarallah has been mixed. Under the umbrella of the Tribal Affairs Authority, the alliance with Ali Abdullah Saleh enabled the Houthis to secure the support — or at least the acquiescence — of tribal shaykhs co-opted by the former president (ACAPS, 13 August 2020). Shaykhs were offered positions in national and local government institutions, and were key to preserving the stability of the alliance at the local level. In December 2017, Saleh failed to mobilize his tribal network after splitting with Ansarallah, suggesting that some tribes had pragmatically shifted towards the Houthis. Signs of tribal disorder have since increased in central and northern Yemen. This may reflect Saleh’s ability to hold together “a broad, trans-sectarian network of tribal alliances” (Al-Deen, 23 April 2019) that stretched beyond the traditional geographical and sectarian areas of Houthi influence, in absence of which discomfort over Houthi domination has surfaced.

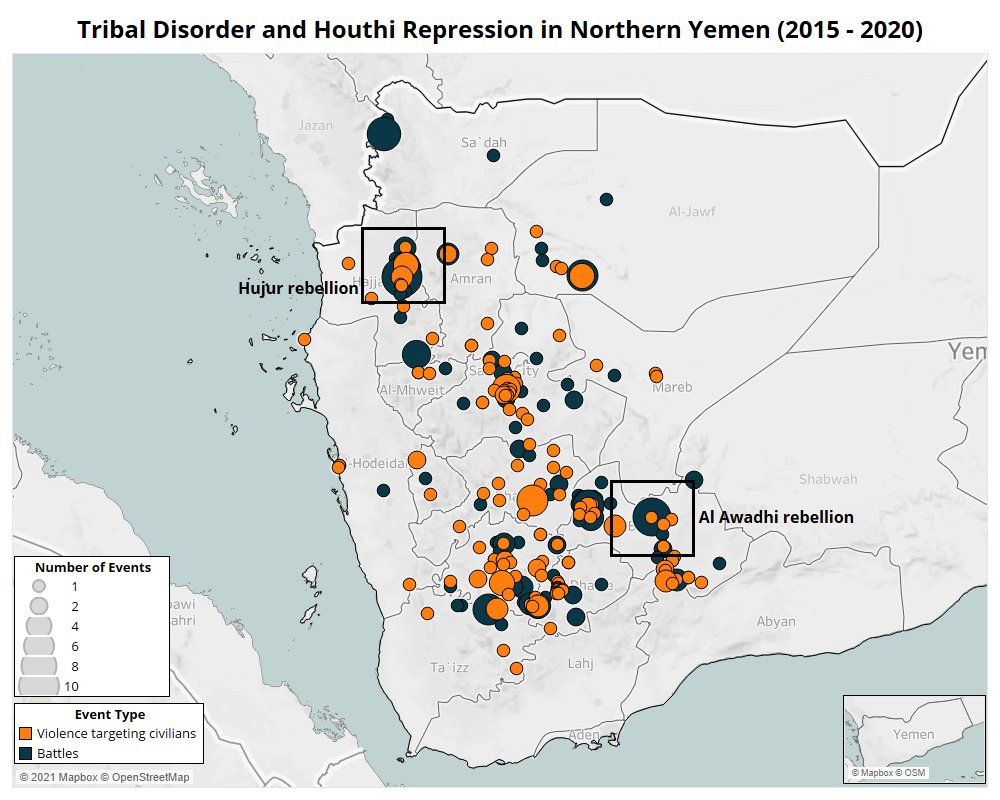

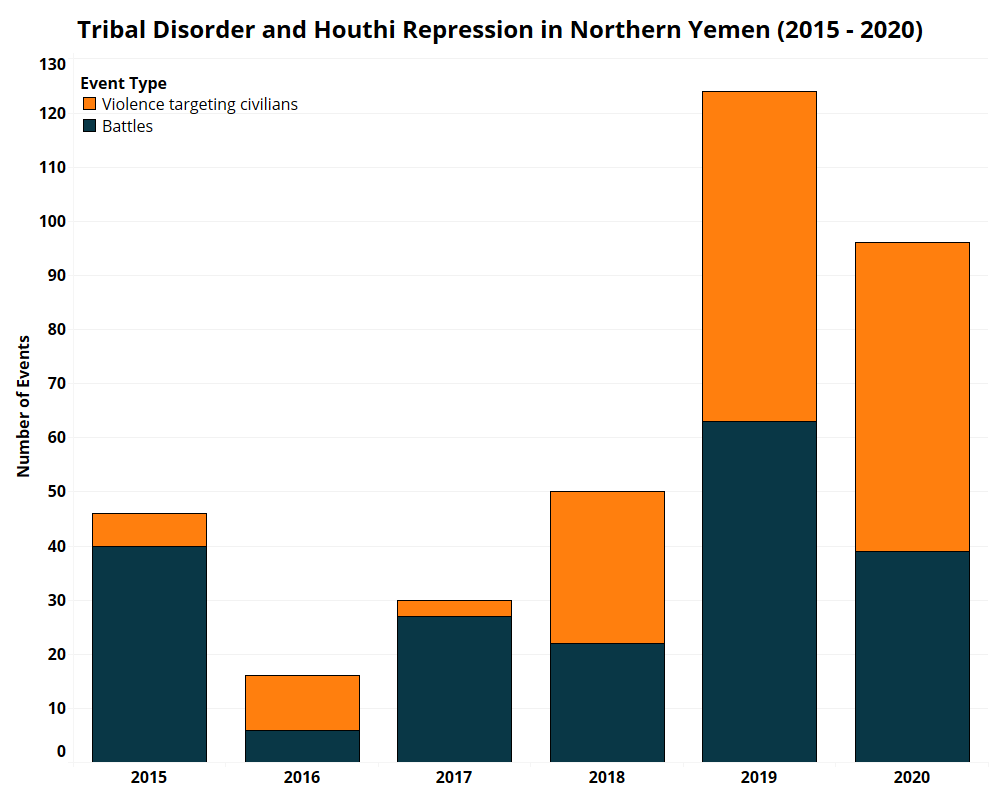

Data collected by ACLED on tribal disorder seem to confirm these trends. In order to delimit the concept of tribal disorder, these data only comprise organized violence events occurring in Houthi-controlled territories, and deliberately exclude the targeting of tribal communities and confrontations with government or coalition-backed tribes along the battlefront. With this in mind, the figure below shows that violent confrontations between Houthi forces and armed tribes peaked in 2019, increasing threefold from the previous year and slightly subsiding in 2020. The increase, however, had already begun in 2018, following the split between Saleh and the Houthis. The figure also reveals that violence targeting unarmed tribespeople and communal groups has substantially increased over the past two years, a reflection of growing Houthi repression.

Tribal disorder has been most intense in Hajjah and Al Bayda, sites of two uprisings launched by the Hujur and Al Awadh tribes in 2018 and 2020. Despite their local character, the dynamics of the two rebellions share remarkable commonalities. Tribal shaykhs from both the Hujur and Al Awadh sided, albeit uncomfortably, with the Houthis in the aftermath of the Saudi-led intervention in 2015 (Al Yaman Al Araby, 18 January 2017; Al Mashhad Al Yemeni, 11 March 2019). Yet, after the killing of Ali Abdullah Saleh, discontent over the repeated incursions in tribal territory and the violations of tribal customs was used to mobilize tribal communities against the Houthis (Al Ayyam, 19 February 2019; ACAPS, 13 August 2020). In response, the Houthis accused influential tribal leaders aligned with the General People’s Congress (GPC) — shaykhs Fahd Dahshoush and Yasser Al Awadhi — of inciting sedition and colluding with foreign forces, in a significant blow to local mediation efforts to prevent the escalation of the conflict (Ansarollah, 1 December 2019; Al Araby, 17 June 2020). Lacking any considerable military support from the government and the coalition, tribal mobilization did not match the greater military capabilities of the Houthis, which eventually succeeded in isolating the tribes and crushing the uprisings (Al Masdar, 29 April 2020; Al-Dawsari, 22 June 2020). In addition to battling with the tribes, Houthi forces were also reported to have looted and shelled tribal villages indiscriminately.

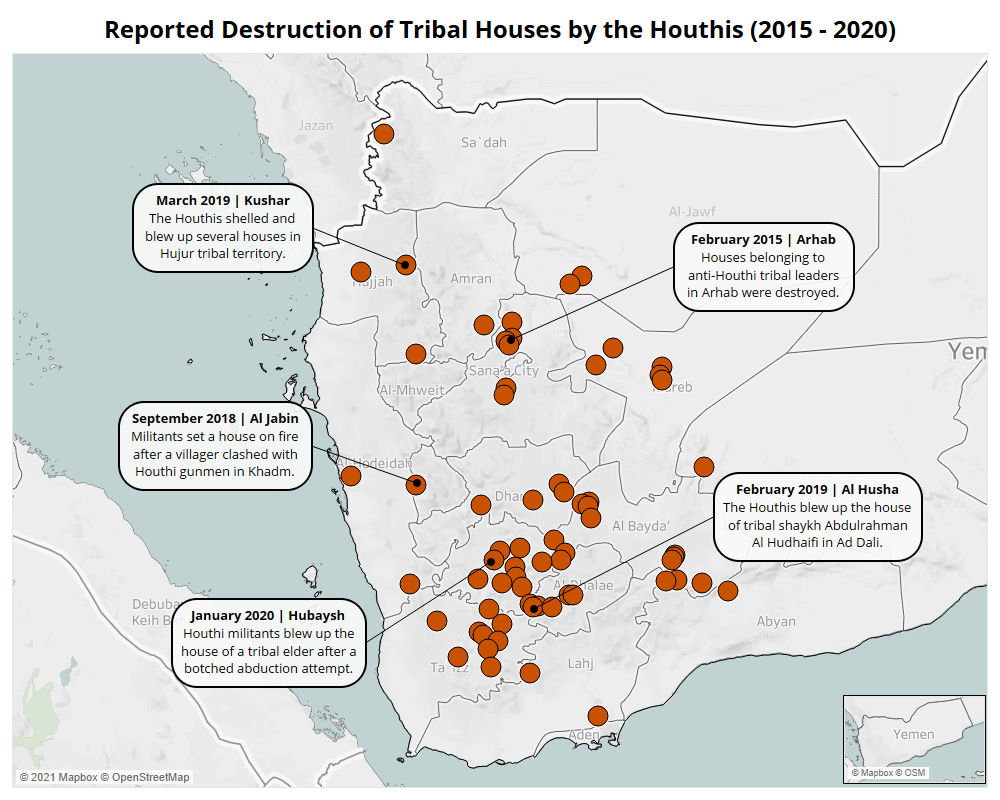

Another element in common between the two uprisings is the reported destruction of tribal homes by the Houthis. According to tribal customs, the house is a sacred space, and any violation or insult to its sacred nature must be compensated (ACAPS, 13 August 2020). Yet, the destruction of a house represents a physical and symbolic humiliation, which can deprive a tribal shaykh of power and respect among his community and beyond. In February 2014, the Houthis blew up the house of the Al Ahmar family in Amran, a warning sign for other tribal shaykhs planning to oppose the Houthi advance in Hashid territory (Al-Dawsari, 17 February 2020). This event was not the last one, and the use of these tactics has in fact intensified throughout the war: data collected by ACLED reveal that the Houthis blew up, burnt, or shelled houses belonging to tribal, community, and party leaders in at least 51 districts across 17 governorates (see figure below).1Events involving the destruction of tribal houses are coded by ACLED either as “Strategic developments” (if involving looting and burning) or as “Explosions/Remote Violence” (if involving the use of shelling, bombs, or other remotely activated devices). The deliberate destruction of tribal houses has typically occurred in response to the emergence of local opposition to Houthi rule, and has been intended to subjugate the insurgents and intimidate potential dissidents (The National, 13 February 2019; Rights Radar, June 2019; Yemen Window, 20 July 2019).

Relationships between the Houthis and the tribes have become increasingly tense since the violent demise of Ali Abdullah Saleh. Without the former president alive to oversee his patronage network and assuage tribal concerns over his allies’ intentions, some tribes of central and northern Yemen have broken ties with the Houthis, sparking short-lived rebellions. The Houthis have responded to mounting tribal opposition with severe repression, resulting in higher levels of violence targeting civilians and breeding further anxiety among the tribes.

Conclusion

While spared by the fragmentation and insurgencies that characterize much of southern Yemen (for more, see ACLED’s analysis series mapping little-known armed groups in Yemen, as well as our recent report on the wartime transformation of AQAP), infighting and repression constitute two major sources of instability in Houthi-controlled territories, and a potential challenge to the survival of the Houthi regime in the coming years. Within Ansarallah, factional infighting has pitted local Houthi commanders against loyalists hailing from the northern governorates, reflecting resentment over the centralizing trends sponsored by the movement’s leadership. The co-option of tribal shaykhs as security or political officials in local government structures has nonetheless brought communal disputes over revenge killings or land property inside the movement itself. Overall, relationships between the Houthis and the tribes have considerably worsened since Ali Abdullah Saleh was assassinated in December 2017, igniting a cycle of revolts and repression.

Yet, this widespread disorder at the local level has not escalated into mass defections from the regime. Divide-and-rule strategies, exemplified by the selective co-option of tribal shaykhs in governance structures, together with the pragmatic considerations of the tribes that are wary of antagonizing Ansarallah, have allowed the movement to navigate these turbulences almost unscathed. Without external support for domestic groups or a collective uprising against Houthi rule — both of which are highly unlikely in the current context of a prolonged war of attrition — there is little chance that these uprisings could turn into a wider challenge for the regime. More likely, infighting and repression will continue to permeate relations between the Houthis and other groups at the local level.