As countries continue to contend with the COVID-19 pandemic, it has become clear that its impact extends far beyond public health and safety, with the ability to shape political behavior and conflict. The interplay between disease and disorder is perhaps most visible in India, which has been one of the nations worst affected by the coronavirus. Following the onset of the pandemic, ACLED records an escalation of conflict in Jammu & Kashmir (for more see this spotlight infographic from ACLED’s COVID-19 Disorder Tracker) as well as a new wave of political unrest in the northeast (for more see this ACLED report on political violence in northeast India). In contrast, ACLED data show a decline in events in 2020 related to the Naxal-Maoist insurgency, one of India’s oldest post-independence conflicts.

The restrictions surrounding the coronavirus pandemic impacted the Naxal-Maoist insurgency in two significant ways. First, the lockdown worsened already strained supply chains, preventing cadres from accessing vital resources such as rations and weaponry. Second, dwindling supplies subsequently affected operational capacity as insurgents were unable to effectively carry out their annual tactical counter-offensive campaign (TCOC). The combination of these factors has led to an overall decline of Naxal-Maoist activity in 2020, compared to the year prior. A comparative analysis of ACLED data for 2019 and 2020 reveals these trends and offer insights into the changing nature of the conflict.

Decline in Active Locations

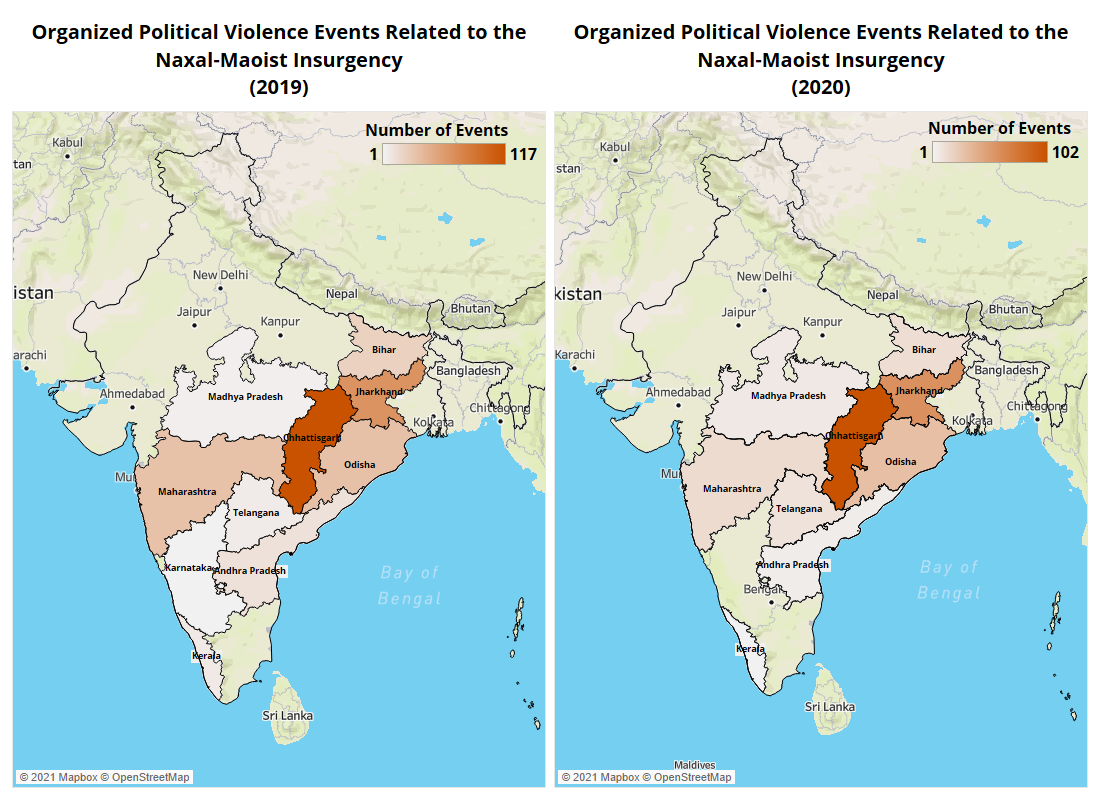

The Naxal-Maoist insurgency, which has been active since 1967, seeks to overthrow the Indian government to establish communist rule within the country. The movement gained significant momentum with the establishment of the Communist Party of India-Maoist (CPI-Maoist) in 2004. At its peak, the insurgency was active in 40% of India’s land mass, with the ‘Red Corridor’ spanning eastern, central, and southern India (South Asia Terrorism Portal, March 2012). However, in its current form, Naxal-Maoist activity has been limited to around a dozen states. In 2019 and 2020, ACLED data indicate that 80% of all Naxal-Maoist activity was concentrated in just four states — Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Odisha, and Maharashtra (see map below).

Decrease in Organized Political Violence1Organized political violence includes the following event types in the ACLED data: Battles, Explosions/remote violence, and Violence against civilians.

Decrease in Organized Political Violence1Organized political violence includes the following event types in the ACLED data: Battles, Explosions/remote violence, and Violence against civilians.

India continues to have the second highest rate of coronavirus transmission, with over 10 million total cases by the end of January 2021 (World Health Organization, 10 February 2021). However, in March of last year, early projections were far higher, with some experts predicting up to 300 million cases (India Today, 21 March 2020). In response to these estimates, the Indian government enforced a strict lockdown beginning on 24 March, suspending all non-essential travel for 21 days, which was extended to three months with some minor relaxations (New York Times, 25 March 2020; Indian Express, 21 May 2020). While the socio-economic implications of these measures have been well documented, the impact of COVID-19 on India’s conflict landscape has received less attention.

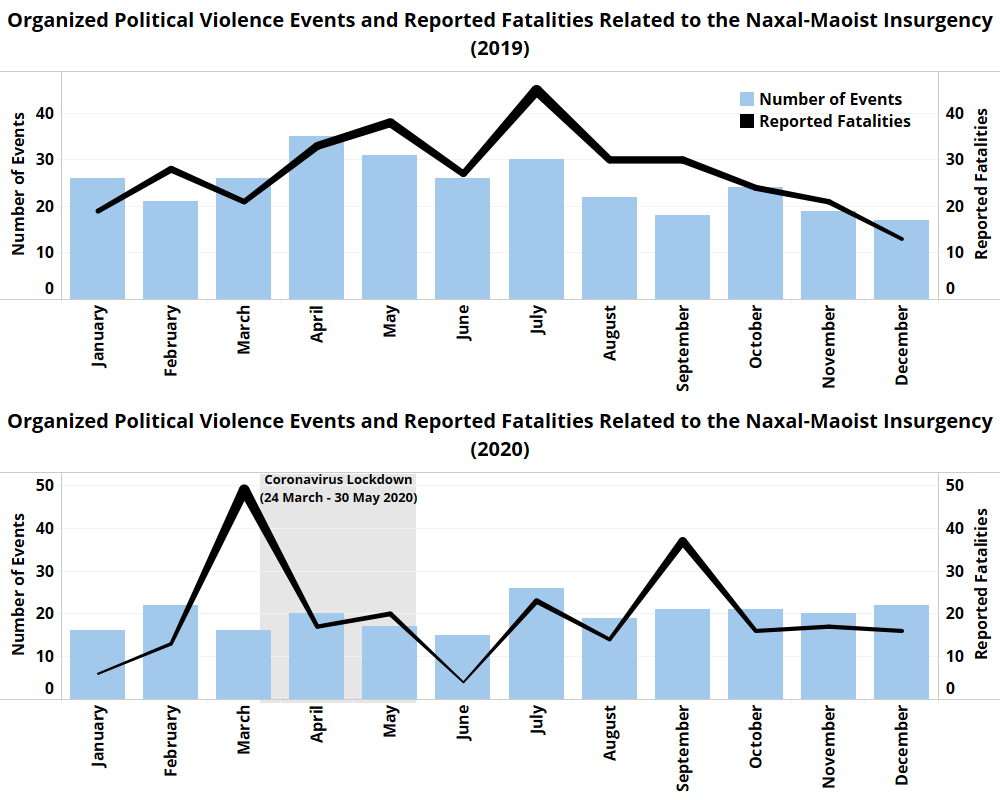

ACLED records a 20% decrease in organized political violence events involving Naxal-Maoist insurgents in 2020 compared to 2019. A total of 235 events were reported, compared to 295 events the year prior (see figure below). Explosions/remote violence events decreased by 35% and events of violence against civilians decreased by more than a quarter. Reported fatalities as a result of these events also decreased by nearly 30%, despite an event with 40 reported fatalities on 21 March 2020, when CPI-Maoist cadres ambushed security personnel in a forest area in Sukma district, Chhattisgarh (Hindustan Times, 12 September 2020).

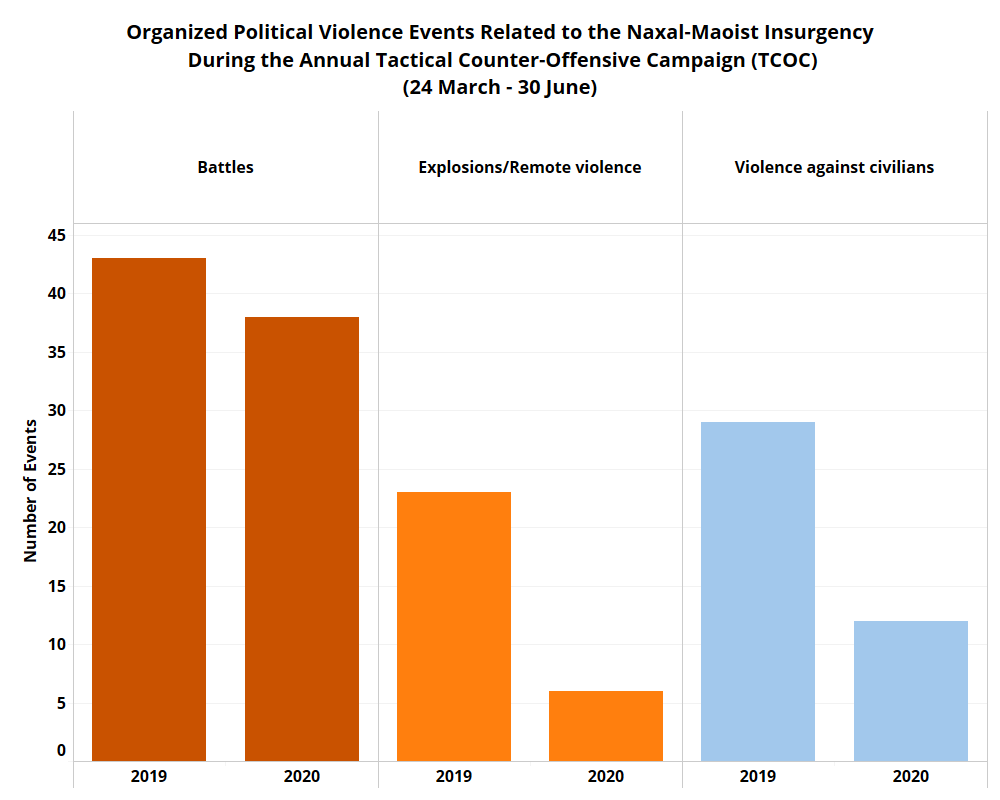

The decrease is particularly notable between the months of March and June, which is when Naxal-Maoist rebels have historically carried out their annual TCOC, which forms the core of Naxal-Maoist battle strategy. The TCOC involves carrying out a quick succession of small and large attacks, often luring security forces into the forests (Diplomat, 31 August 2020). The period coincided with the onset of coronavirus lockdown restrictions at the end of March 2020 and gradual reopening in June 2020. Between 24 March and 30 June 2020, ACLED records a more than 40% decrease in violent events compared to the same period in 2019 (see figure below).

The nationwide lockdown significantly impacted already strained Maoist supply chains, which further weakened their strength and operational capacity (Print, 21 April 2020). Unlike other insurgent movements in India, the Naxal-Maoist movement is people-centric, with a heavy dependence on grassroots supply chains. In order to obtain essential commodities such as food and medicine, militia cadres typically take rations from local haat bazaars or village markets held in remote areas (Economic Times, 18 April 2020). The closure of these markets amid the pandemic lockdown has drained the Naxal-Maoist insurgency of key resources. This is best exemplified in the Maoist stronghold of Bastar district in Chhattisgarh state, where, due to the three-week forced closure of 480 haat bazaars in March and April, rebel forces were targeting the public distribution system meant for villagers to gain access to food supplies (New Indian Express, 15 April 2020).

The heightened restrictions on movement also contributed to a lack of access to resources, specifically in terms of weapons procurement. Weapons and ammunition are typically sourced from a combination of manufacturing arms in factories within Naxal-Maoist strongholds, and procuring arms by bribing or coercing local security forces and villagers (OneIndia, 30 May 2018, Times of India, 28 September 2020). With increased internal checkpoints established by security forces at interstate and inter-district borders, as well as the subsequent suspension of movement of goods, it is likely that the insurgency’s operational capacity was impinged. This subsequently led to a loss of tactical momentum during the strict lockdown imposed in the first half of the year (Times of India, 12 September 2020).

Regionally, Chhattisgarh remained the central stronghold for the Naxal-Maoist insurgency in 2019 and 2020 (see map above). Still, the state saw a 13% decrease in events in 2020 compared to the year prior. Similarly, the number of events in Maharashtra, Bihar, and Andhra Pradesh combined decreased by 55%. While these trends re-affirm aforementioned factors like disrupted supply chains and loss of tactical momentum, they may also point towards a gradual decline of Maoist influence in the region due to the regular loss of lower rung cadres and increased surrenders due to “disillusionment over a hollow ideology” (Times of India, 12 September 2020; Hindustan Times, 27 January 2021). During the lockdown period, it was also reported that rebels have been using the time to regroup in traditional strongholds such as Bastar district in Chhattisgarh, and recruit new cadres from neighboring states (Outlook, 16 April 2020).

Resurgence of Violence and Future Trends

Despite the overall decline in Maoist violence in 2020, ACLED records a significant uptick of Maoist activity during the second half of the year: 55% of all violent events involving Naxal-Maoist actors were reported in the second half of 2020, from July to December, coinciding with the gradual reopening beginning in June. Between July and December 2020, in Odisha and Jharkhand state, the number of events surpassed those recorded during the same period in 2019. While this could indicate a normalization of operations, there has also been an increase in mass surrenders by cadres in late 2020 and early 2021. With this in mind, it is unclear if the influence and operational strength of the Naxal-Maoist insurgency has significantly shifted as a result of pandemic restrictions. The impending TCOC offensive in the coming summer months will be indicative of the insurgency’s vigor in 2021.

Decrease in Organized Political Violence

Decrease in Organized Political Violence