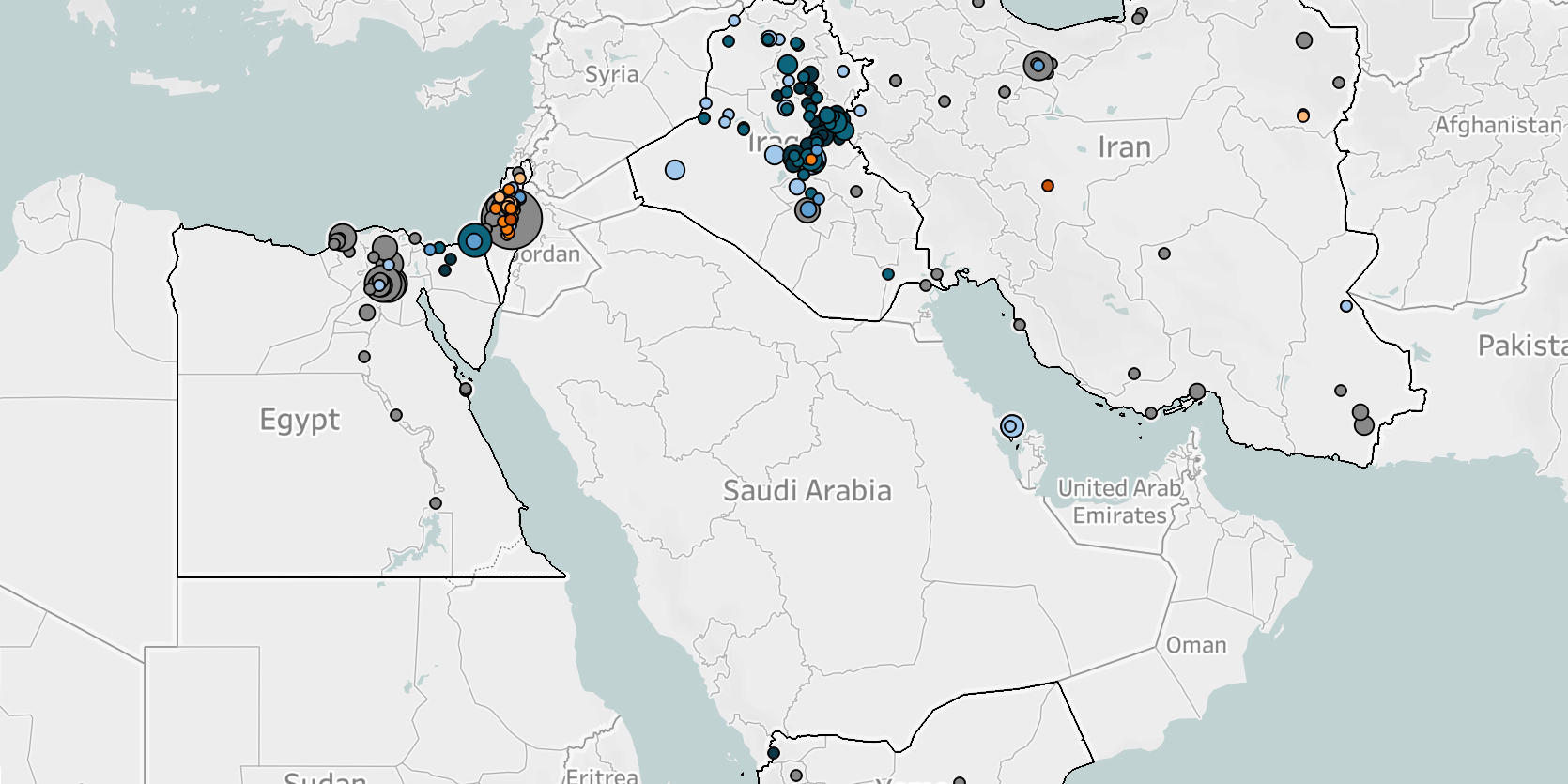

In the past month, the situation in Bahrain was marked by reactions from the Shiite population to a royal decree issued in January that changed the administration of the religious endowments directorates. The Bahraini Shiite community was also targeted for their religious practices. In Egypt, the repression of Muslim Brotherhood members and the use of the Muslim Brotherhood affiliation to repress activists who are unlikely to have any relationship with the organization took place on a weekly basis. In Iran, repression of religious minorities continued, including cases that made international headlines. In Iraq, Shiite militias targeted places like liquor stores and massage centers on a weekly basis in Baghdad. In Israel, the easing of coronavirus restrictions led to a drastic decrease in the dispersal of Jewish gatherings by police forces. Haredi Jews, however, continued to hold demonstrations against perceived attacks on their faith. In Palestine, tensions flared around the Al Aqsa compound in Al Quds city, with a notable spike around the Jewish Purim holiday. In Yemen, pro-Houthi forces and authorities have imposed religious norms and practices across the territories under their control. Meanwhile, pro-Southern Transitional Council (STC) forces seem to have launched a new campaign targeting alcohol production in the south of the country in late February.

In Bahrain, a number of Shiite leaders denounced the recent royal decree that created new boards of directors for the religious endowments directorates on 20 January 2021. Although the decree targets both the Sunni and Jaffaria Endowment Directorates, it has been decried by many Shiite activists as an attempt to further increase the government’s control over Shiite religious affairs (Twitter, 6 February 2021). The move was denounced as “illegitimate” and a “sinful violation” on 6 February by Ayatollah Sheikh Isa Qassim, who was stripped of his Bahraini citizenship in 2016 and now resides in Iran, yet remains a spiritual leader for much of the Bahraini Shiite population (Bahrain al Youm, 7 February 2021).

Bahraini authorities also targeted Shiite citizens for their religious practices last month. Notably, Shiite citizens were arrested and sentenced for their participation in the 2020 Ashura commemorations that took place last August. During Ashura, Shiite worshippers gather in congregation halls to commemorate the martyrdom of Imam Husayn in the battle of Karbala. Although restrictions around Ashura have been particularly strict this year due to the ongoing pandemic, Bahraini authorities are reported to systematically target the Shiite population during these annual events (Bahrain Interfaith, 10 November 2014).

In Egypt, judiciary authorities have built cases on charges of affiliation with the Muslim Brotherhood to quell any form of opposition to the regime on a weekly basis. More than seven years after the fall of the Morsi government in 2013, they are notably still prosecuting Morsi era politicians. On 20 February, for instance, a criminal court ordered that 21 individuals, including an adviser to former President Morsi, be added to the “terrorist list” for a period of five years on accusations of taking part in “terrorist activities” for their affiliations with the Muslim Brotherhood (El Fagr News, 20 February 2021). In addition, they have accused a number of political leaders, activists, journalists, and lawyers of taking part in the activities of the Muslim Brotherhood. The charges of all of these cases, however, have been challenged by human rights organizations. These cases include those for leaders of the Civil Democratic Movement, the April 6 Youth Movement, and the Strong Egypt Party.

In Iran, the death of Sufi Gonabadi Dervish Behnam Mahjoobi in mid-February, after he was reportedly denied access to adequate medical care in prison, attracted media attention. Mahjoobi’s death was used by some organizations to remind the public of the repression of religious minorities in Iran (USCIRF, 24 February 2021). He was initially arrested for taking part in the 2018 Dervish protests, during which a number of Gonabadi Dervishes denounced the arrest of a member of their community in Tehran. These escalated into clashes with police forces over several days, resulting in a number of deaths on both sides, and the subsequent arrest of more than 300 dervishes (Al Jazeera, 27 February 2018).

As well, among several events targeting Baha’is in Iran, two properties belonging to Baha’i citizens were confiscated in Hormozgan province in late February, shedding on the latest prominent case. Last October, a court order was issued for the confiscation of all Baha’i residences in the village of Ivel in Mazandaran province, with debates reemerging about the legality of such cases (IranWire, 18 February 2021). Some ayatollahs argue that Baha’is are “infidels and have no right to property” (IranWire, 18 February 2021).

With regards to the legal environment around religion in Iran, President Hassan Rohani signed two new provisions to Iran’s Islamic Penal Code on 18 February that punish anyone who “insults the legally-recognized religions and Iranian ethnicities” (Article 19, 19 February 2021). Due to the ambiguity of the full wording, some believe that these will provide a “fertile ground for arbitrary arrest” and will “disproportionately impact individuals belonging to religious and faith-based minorities and ethnic groups” (Article 19, 19 February 2021).

In Iraq, Shiite militias have increasingly been claiming responsibility for attacks targeting liquor stores and massage centers with explosives in Baghdad. In a number of instances, however, the perpetrators remain unknown, and the reasons behind the attacks remain unclear. Some explanations emphasize the Christian and Yazidi identities of the store owners. Others, argue that these attacks are part of a territorial conflict vying for influence since Muslim citizens are allowed to own such stores and compete with the traditional Christian and Yazidi owners (France 24, 16 December 2020).

In early February, the Peace Companies, a paramilitary group answering to Shiite cleric Muqtada al Sadr, engaged in the repression of activists in Najaf province following a demonstration against their leader (Rudaw, 7 February 2019). On 8 February, they deployed tens of thousands of men in the cities of Baghdad, Karbala, and Najaf claiming to be acting on intelligence about a plot against holy sites. During these deployments, they reportedly raided the houses of protesters. At least one activist was reportedly abducted and tortured in Najaf (Iraqi Center for Documenting War Crimes, 14 February 2021; Twitter, 14 February 2021). While Al Sadr initially sided with anti-government protests in the October 2019 uprising, he dissociated himself from the movement in February 2020, and his forces have since turned against protesters on a number of occasions (Al Jazeera, 27 November 2020).

In Israel, the first part of February was marked by a number of police operations targeting Jewish gatherings held in violation of coronavirus restrictions across the country — in particular weddings and religious educational institutions. The Haredi city of Bnei Brak was notably targeted. A number of Haredi Jews have indeed denounced and refused to adhere to coronavirus restrictions, claiming that the restrictions prevent them from practicing core elements of their religious identity (Israel Democracy Institute, 13 April 2020). On 9 February, for instance, thousands of Haredi Jews violently demonstrated in Jerusalem against the closure of synagogues and religious educational institutions, as well as the perceived targeting of their community (Kikar HaShabbat, 9 February 2021).

In the second half of February, however, these events decreased drastically, coinciding with the general reopening of the country, though a number of restrictions around religious celebrations remain. Authorities, for instance, closed the tomb of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai from 18 to 21 February over the commemoration of Moses’ death (Seventh of Adar). They also implemented a nationwide curfew for three days on 25 February around the Jewish Purim holiday. The country’s vaccination strategy against the coronavirus has granted it the status of “world leader,” with around 40% of its population already fully inoculated (The Guardian, 3 March 2021; France 24, 7 March 2020). However, it has also received heavy criticism for providing very few doses to the Palestinian population living under Israeli control (The Guardian, 3 March 2021).

In Palestine, much of the religious tension is concentrated in Al Quds city, where the Al Aqsa compound reopened to Muslim worshippers after a 45-day closure on 12 February (Times of Israel, 12 February 2021). This closure, however, did not prevent Israeli settlers from entering the site and practicing Talmudic rituals, which is forbidden according to the status quo affirmed in 1967 (Al Jazeera, 14 September 2020). Moreover, the number of settlers who entered the compound increased significantly after Orthodox organizations called to intensify Jewish access to the site on 27 February, as part of the Jewish Purim holiday. In the largest incursion recorded, as many as 230 settlers entered Al Aqsa on 28 February.

In Yemen, pro-Houthi forces have been imposing religious ideology on different subsets of the population living in their territory. Examples include forced attendance of so-called ‘sectarian courses’ for doctors, nurses, university professors, school directors, and shop owners. These are often accompanied by threats of dismissal from their positions if they do not attend, which have sometimes been carried out. Targeting women, pro-Houthi forces also raided several restaurants for continuing to employ women as waitresses. In late January, pro-Houthi authorities initiated a campaign against gender-mixing in restaurants, on the basis that it was against the “Yemeni religious identity” (Al Mashhad al Yemeni, 28 January 2021; Khabar News Agency, 28 January 2021).

On several occasions, this attempt at imposing religious beliefs reached places of worship. On 19 February, pro-Houthi authorities closed a number of mosques in the Sanhan district of Sanaa in an attempt to force worshippers to attend Friday sermons in mosques run by preachers following the Houthi ideology. On 5 March, a Houthi supervisor also expelled worshippers from a mosque in Ibb governorate after they refused to listen to his sermon. In both instances, worshippers reportedly organized prayers in outdoor areas as a sign of protest (Al Mashhad al Yemeni, 19 February 2021; Al Mashhad al Yemeni, 6 March 2021)

In Southern Yemen, pro-STC forces have launched a campaign targeting alcohol producers in Aden in late February, explicitly enforcing Sharia. From 26 February to 2 March, five supposed alcohol production locations were thus raided in the city and a number of vendors were arrested. The forces leading the campaign claim that they are getting rid of “destructive elements that are prohibited by Sharia and the law of the state,” and which “disrupt the stability and security of the region” (Hadramawt 21, 28 February 2021). The frequency of these events could intensify in the coming weeks.

All ACLED-Religion pilot data are available for download through the ACLED-Religion export tool. Explore the latest data with the interactive ACLED-Religion dashboard.