Since 2019, Bolivia has been in a state of political turmoil. Accusations of election fraud during the presidential election that year led to the resignation of longtime President Evo Morales. This event motivated many Bolivians, including supporters of Morales’ party, the left-wing Movement for Socialism (MAS), to demand more transparency from both government institutions and political parties. As MAS has returned to power with the election of President Luis Arce in 2020, members and supporters of the party have demonstrated to call for more open political processes. Recent mobilization has centered on the selection process for municipal candidates amid questions over Morales’ continued control of the party. Aggravating the political unrest, Bolivia now faces an unprecedented economic crisis amplified by the coronavirus pandemic (Societe Generale, 31 October 2020).

In the midst of political and economic tensions, municipal elections were carried out on 7 March 2021. Preliminary pool results indicate that MAS candidates are behind in at least 10 large cities (El Deber, 8 March 2021). Though it will take weeks to see official results for different levels of the government, the outcome will have significant repercussions for Bolivia’s political stability in the coming years.

The 2019 Political Crisis

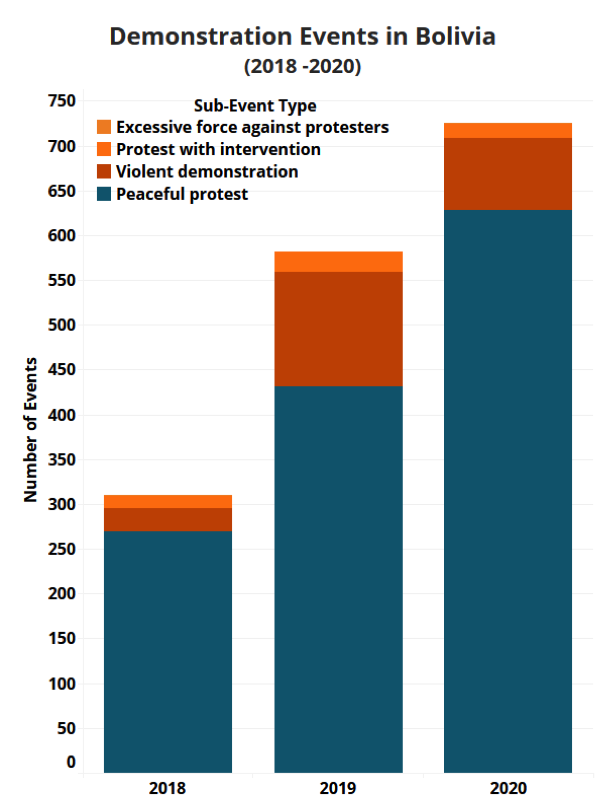

In October 2019, when former President Morales resigned and fled the country after 13 years in power, Bolivia entered a state of political crisis. Morales was accused of election fraud by the opposition, which led to widespread demonstrations against his alleged victory in the presidential elections (for more, see the Bolivia section in ACLED’s Disorder in Latin America: 10 Crises in 2019 report). The roots of the 2019 crisis date back to February 2016, when Morales ignored the results of a referendum that banned him from running for president again. Morales’ efforts to extend term limits have been perceived by some analysts as an authoritarian bid to hold onto power (Reuters, 28 November 2017). Since 2019, demonstrations over government abuses of power have increased in the country (see figure below).

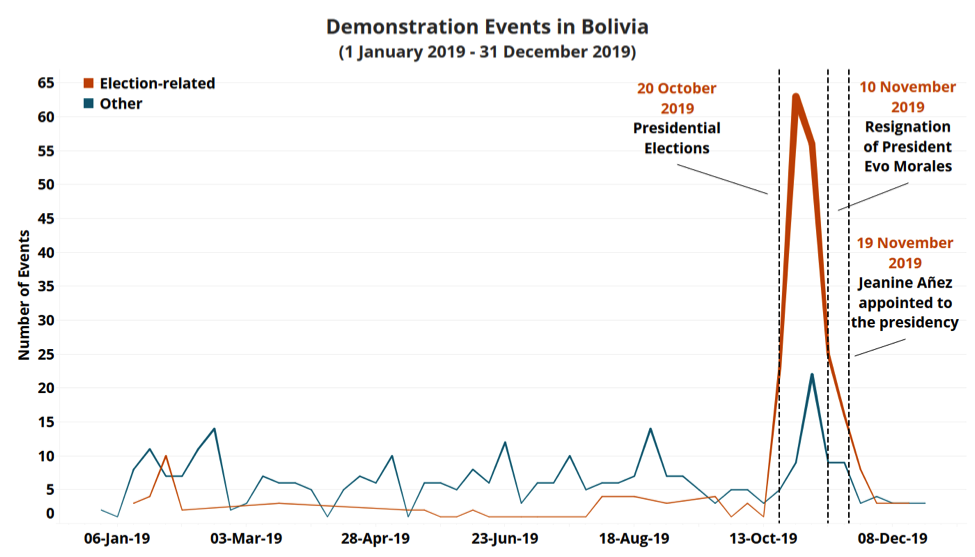

After the election fraud accusations, long-time supporters who began questioning Morales in 2016 rejected his attempts to hold onto power. Approximately 70% of all demonstrations recorded in Bolivia during 2019 occurred in the immediate aftermath of the October elections, with demonstration events peaking during the first weeks of November (see figure below). Jeanine Añez, who was the second vice president of Bolivia’s Senate, was appointed as interim president on 19 November 2019, with the stated objective of carrying out new presidential elections. However, her rise to power was also met with protests, with demonstrators claiming that her right-wing government was persecuting political opponents and trying to use the pandemic as an excuse to retain power (Guardian, 1 June 2020) (for more on this, see ACLED’s Political Limbo: The 2020 Bolivian General Election infographic).

The 2020 Presidential Elections

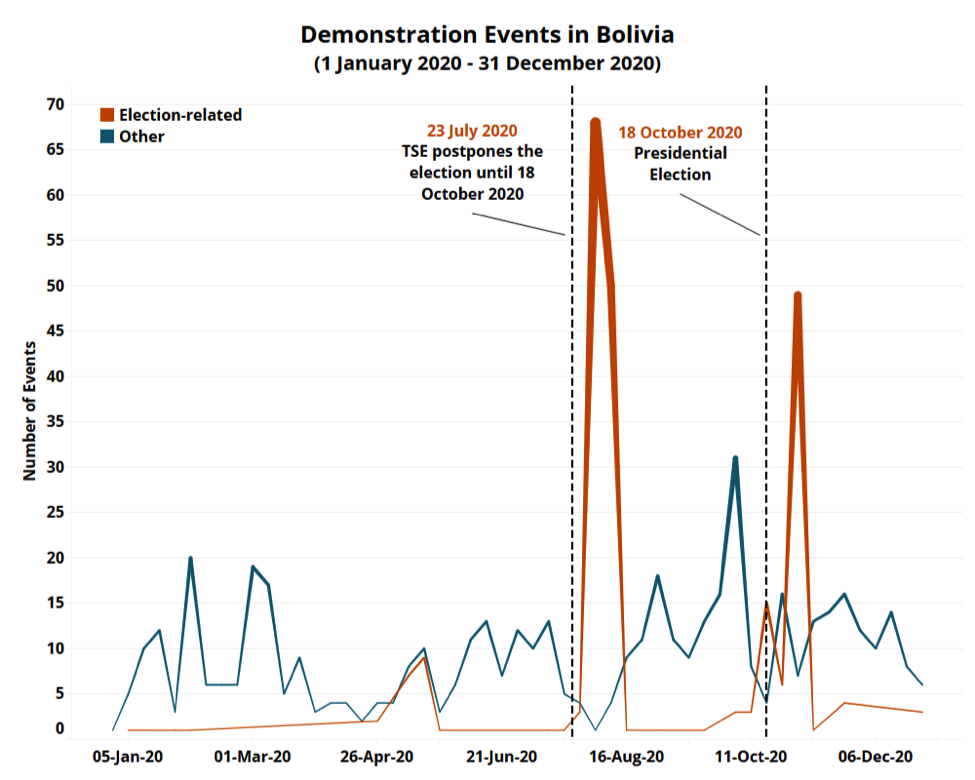

In 2020, the Añez government faced new challenges. The economic and health impacts of the coronavirus pandemic complicated the interim government’s decision to select a suitable date for the presidential elections. With the need to implement effective social distancing measures, the election was ultimately postponed three times (BBC, 23 July 2020). Elections were first expected to take place on 3 May, but were postponed by the Supreme Electoral Tribunal first to 17 May, and later to 6 September. A final postponement set the polls for 18 October.

The postponements sparked multiple demonstrations throughout the year, with events peaking between June and August 2020, when the government announced the final date for the elections (New York Times, 7 August 2020) (see figure below). On 18 October, Luis Arce, Bolivia’s former Economics and Finance Minister, won the presidential election with 55% of the vote (BBC, 20 October 2020). As the MAS candidate, Arce’s victory meant that Bolivians chose to return Morales’ party to power after the 2019 crisis. This is partly because of the general public’s trust and confidence in Arce based on his previous work as minister. During his tenure from 2006 to 2017 and later during 2019, Arce was responsible for policies that led to the biggest economic boom in the country’s history (Deutsche Welle, 12 July 2019).

Arce’s victory, however, was met with dissatisfaction by citizens who opposed MAS in several departments, including Cochabamba, Santa Cruz, and La Paz, which are the three most populous of the country’s nine departments (National Institute of Statistics of Bolivia, 2012). Citizens opposing MAS’ return to power demanded an audit of the election process to verify Arce was the legitimate winner. Additionally, one day before outgoing congressional representatives were to leave their positions, Bolivia’s Congress approved a law that annulled the two-thirds vote requirement in the Assembly and Senate to pass a bill (CNN Español, 29 October 2020). The new law allows the government to pass legislation with a majority, jeopardizing the opposition’s ability to block laws.

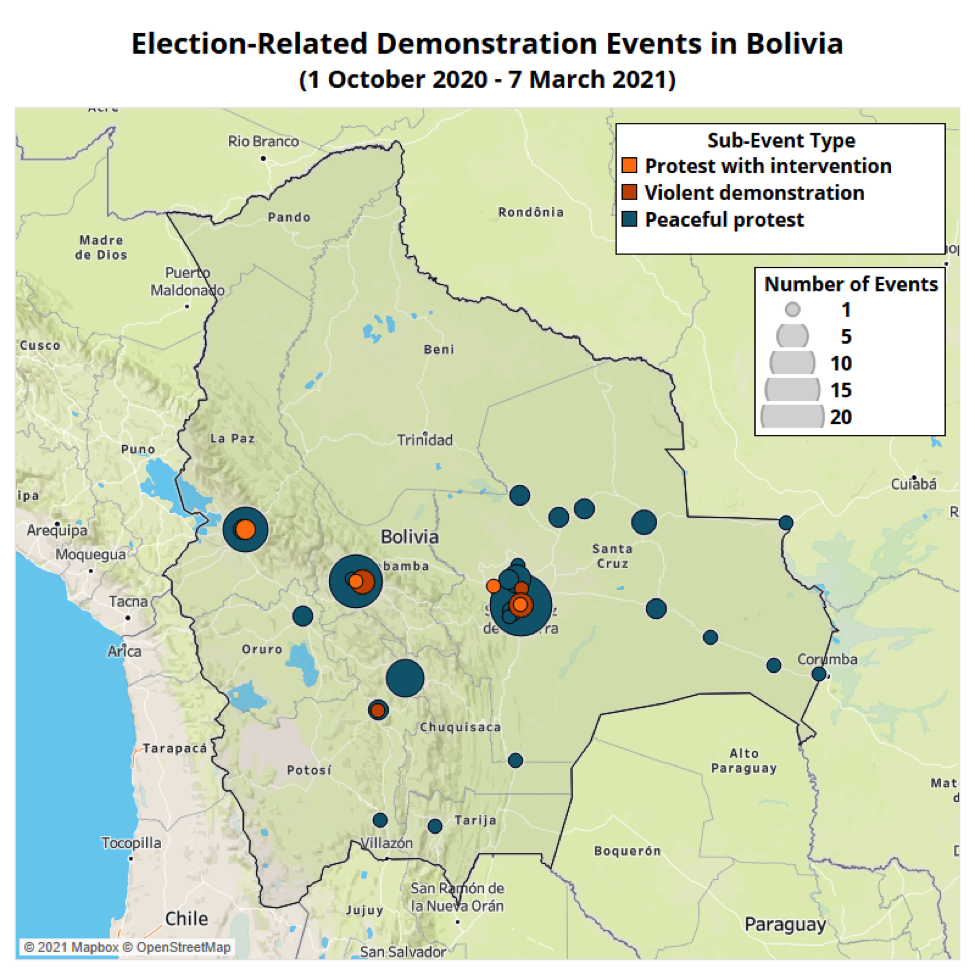

During the first week of November, most demonstrations were carried out in the aforementioned regions, accounting for approximately 50% of the events registered during the month (see map below). While Cochabamba is a long-time stronghold of MAS, and the department where the party originated, the population in Santa Cruz is known to oppose MAS. Santa Cruz is also where the headquarters of the main right-wing political alliance — the ‘We Believe’ coalition (Creemos, in Spanish) — is located. Meanwhile, La Paz, the administrative capital of the country, tends to lean towards left-wing parties, including MAS and the ‘Civic Community’ coalition (Comunidad Ciudadana, in Spanish). The main demand of protesters across departments was transparency in the political and electoral processes. They claimed they would not accept results without an audit. Nevertheless, the audit was not approved by the Supreme Electoral Tribunal, and Arce’s victory was ultimately backed by the institution (Europa Press, 4 November 2020).

The 2021 Municipal Elections

After spending one year in exile in Argentina, Morales returned to Bolivia on 9 November 2020, after MAS regained power. With municipal elections scheduled for March 2021, Morales reasserted influence over the party by leading the selection and appointment of MAS candidates. On 7 March, citizens chose the representatives of regions, departments, and municipalities of Bolivia. The implications of Morales appointing candidates, however, were noticed by MAS followers, who rejected said candidates, claiming that the selection process was biased in favor of the former president’s preferences. MAS supporters became divided into followers of Morales, on one hand, and another group seeking new leaders to advance the party’s policies, on the other. Similar to the renewal at the national level, with Arce as president, many MAS supporters called for new leadership to represent the party when competing for different local government positions.

During a candidate announcement meeting led by Morales in Shinahota city in the Cochabamba department, MAS supporters were outraged by the candidate selected for mayor. They claimed the candidate was a protegé of Morales and did not represent the locals’ demands. The event escalated violently, and rioters threw objects and a chair at the former president and other heads of the party (Correo del Sur, 15 December 2020). The rejection of the candidates selected by Morales was not limited to Shinahota, but also occurred in Betanzos, Colcapirhua, and El Alto cities, among other locations where the candidates chosen were rejected by MAS supporters and members.

Both average MAS supporters and loyal representatives backed an unbiased selection process. This included Eva Copa, the former Congress president and an important figure in the party. After being excluded as candidate for Mayor of El Alto city, she claimed that party leaders were biased against her, choosing another candidate despite the endorsement of her appointment by several local social organizations. This led Copa to leave MAS and join another left-wing party, the Jallalla La Paz, with the support of social organizations backing her candidacy (El Deber, 28 December 2020). The Ponchos Rojos movement, which was known to support Morales, also rejected the selected candidates, and asked the party to give opportunities to new people (Correo del Sur, 15 December 2020). While both Copa and the Ponchos Rojos movement share the left-wing ideology of MAS, they ultimately rejected the heads of the party and the candidates selected.

Additionally, the MAS presidential victory influenced its supporters to take control of the management of social and workers’ funds, which they claimed should be managed by members of their political party, and not by people chosen during the previous Añez government. These public funds work as social and health insurance for unionized workers who financially contribute to the funds’ local offices. They are often managed by appointees from the government, which can lead to disputes on the grounds that they favor whoever is in power. Workers therefore have a serious incentive to participate in the decision-making process and management of these institutions.

In this context, there were attempts mainly led by MAS supporters to take over the control of the offices of several public funds, including the Coca Producers Department Association (ADEPCOCA), the Oil Industry Health Fund of Santa Cruz, and the Health Fund of Roads offices. The occupations were often violent. At least five events have been reported across the country. They are likely to continue after a judicial decision appointed a member of MAS as president of ADEPCOCA on 17 February (Pagina Siete, 17 February 2021). Rioters tried to occupy ADEPCOCA offices by force several times without success. The occupation attempts were repudiated by those opposed to MAS, which included some of the managers in charge of the funds. The riots to occupy public funds offices accounted for approximately 11% of all riot events reported in the country from November 2020 to February 2021.

While the official results of the municipal elections will take weeks to be released, preliminary pool results indicate that the candidates selected by Morales and the heads of the MAS party are behind in at least 10 large cities (El Deber, 8 March 2021). This reinforces the previous trend of demonstrations being held against the running MAS candidates. For instance, preliminary results indicate a victory for Eva Copa, who, as noted, left MAS following disagreements with leaders (Correo del Sur, 8 March 2021).

Tensions have also increased in the country in the past week, with the arrest of former interim President Áñez, on the grounds that she was part of a coup to remove Morales from power in 2019 (The Guardian, 14 March 2021). It remains to be seen how both MAS and the opposition will react to this development.

Conclusion

Analysis of recent demonstration patterns gives an indication of how Bolivians want to be governed, and how they perceive the role of the government. Following Arce’s victory, it is evident that the left-wing project is backed by more than half of the country’s population. However, many on the left call for more transparency and legitimacy for political processes in a departure from the way that Morales has led the country in the past. This is a trend observed by the recent rejection of candidates appointed by Morales for MAS, together with the demands for changes in the local management of social and workers’ organizations. Recent demonstration trends show that, if the wishes of the citizens and supporters of the party are not heard, there will likely be more social unrest.