Protesters have been gathering in front of the former Japanese Embassy in Seoul, South Korea every Wednesday since January 1992. They call on the Japanese government to officially apologize to Korean victims who were coerced to render sexual services to Japanese military personnel before and during World War II (The Korean Council, 2021). The surviving victims and their supporters advocate for a just resolution to the sexual violence against ‘comfort women’ — those women forced to provide sexual services to Japanese officers and soldiers (Asian Women’s Fund, 2021). As one of the longest-running protest movements in South Korea, the ongoing demonstration movement has gathered broader support over time; has expanded geographically; and, despite obstacles, has continued to be a barometer for Japan-South Korea relations. This report examines five key elements of these demonstrations between January 2018 and December 2020, including the leading role of the Korean Council, the other main actors involved in the movement, the geographic spread of the demonstrations, increased counter-protests, and rising anti-Japan sentiment. As the issue of ‘comfort women’ remains unresolved despite nearly three decades of demonstrations, the movement is likely to persist due to broad support across Korean society, resilience in the face of counter-protest movements, and tense relations between Japan and South Korea.

Pivotal Role of the Korean Council

Since its first peaceful protest in Seoul in 1992, the Korean Council has served as the main organizer of the weekly ‘comfort women’ demonstrations over the past 29 years (The Korean Council, 2021). From the start of ACLED’s coverage of South Korea in January 2018 to the end of December 2020, the Korean Council has participated in at least 161 demonstrations — approximately 69% of all events related to ‘comfort women’ in the country. These demonstrations predominantly focus on: demanding an official apology from the Japanese government; criticizing the passive and evasive attitude of the South Korean government on settling the ‘comfort women’ issue; and condemning a revisionist history of the situation pushed by certain professors, historians, and conservative civil groups. The Korean Council has raised awareness of the ‘comfort women’ issue through these weekly demonstrations. This has in turn driven other civic groups to host, sponsor, and attend events to express solidarity with the movement and to support their demands, which is what has made the role of the Korean Council pivotal.

Diverse Groups of Protesters

While the Korean Council has remained at the forefront of organizing these demonstrations, a range of other social groups and the public at large have also advocated for justice for the victims. Of note, 80 events — 34% of total ‘comfort women’ demonstration events — were attended by student groups between 2018 and 2020. These students, ranging from K-12 to university students, have both participated in demonstrations led by others and have also independently organized their own. The active participation of younger generations in the movement points to its potential for continuity for generations to come if grievances are not resolved.

Additionally, politicians, the religious community, labor groups, and other civil society groups have also organized and attended ‘comfort women’ demonstrations. Surviving victims and their families from South Korea and other similarly affected countries, like the Philippines, have been active in demonstrations as well. Protesters from China, Japan, Indonesia, the United States, and the United Kingdom have joined the demonstrations to show support. The wide array of supporters points to the ability of the movement to cross-cut numerous groups, which allows for a wider support base. That, coupled with international support, also points to the long-term sustainability potential of the movement.

Nationwide Demonstrations

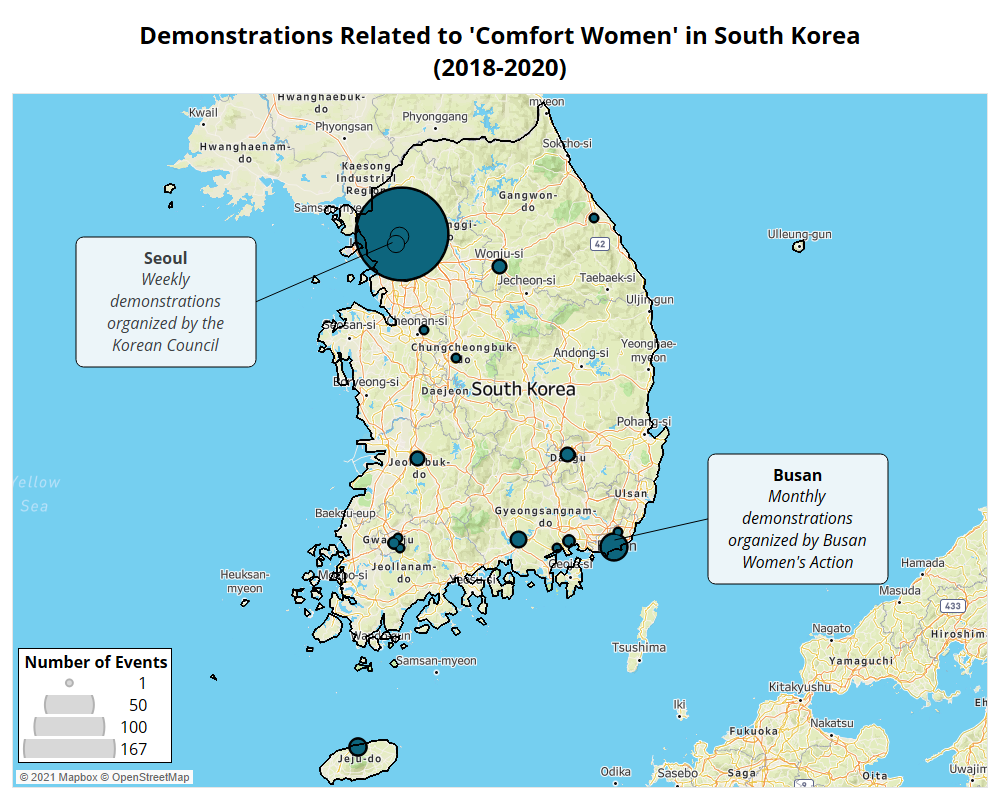

Demonstrations about the ‘comfort women’ issue have occurred across the country and have attracted local activists as well. While most of these demonstrations have taken place in Seoul, about 20% have been organized outside of the capital city, regularly reported in a range of different localities (see map below). Women’s organizations, human rights groups, labor groups, and local civic groups based outside of Seoul have been active in organizing these demonstrations. For example, the Busan Women’s Action group, composed of about 10 local women’s organizations, has held Wednesday demonstrations in front of the Japanese Consulate in Busan on the last Wednesday of every month since January 2016. The geographic scope of these demonstrations is another example of how deep-seated and widespread the issue is across the Korean society and landscape.

Rise of Counter-Protests against Wednesday Demonstrations and the Korean Council

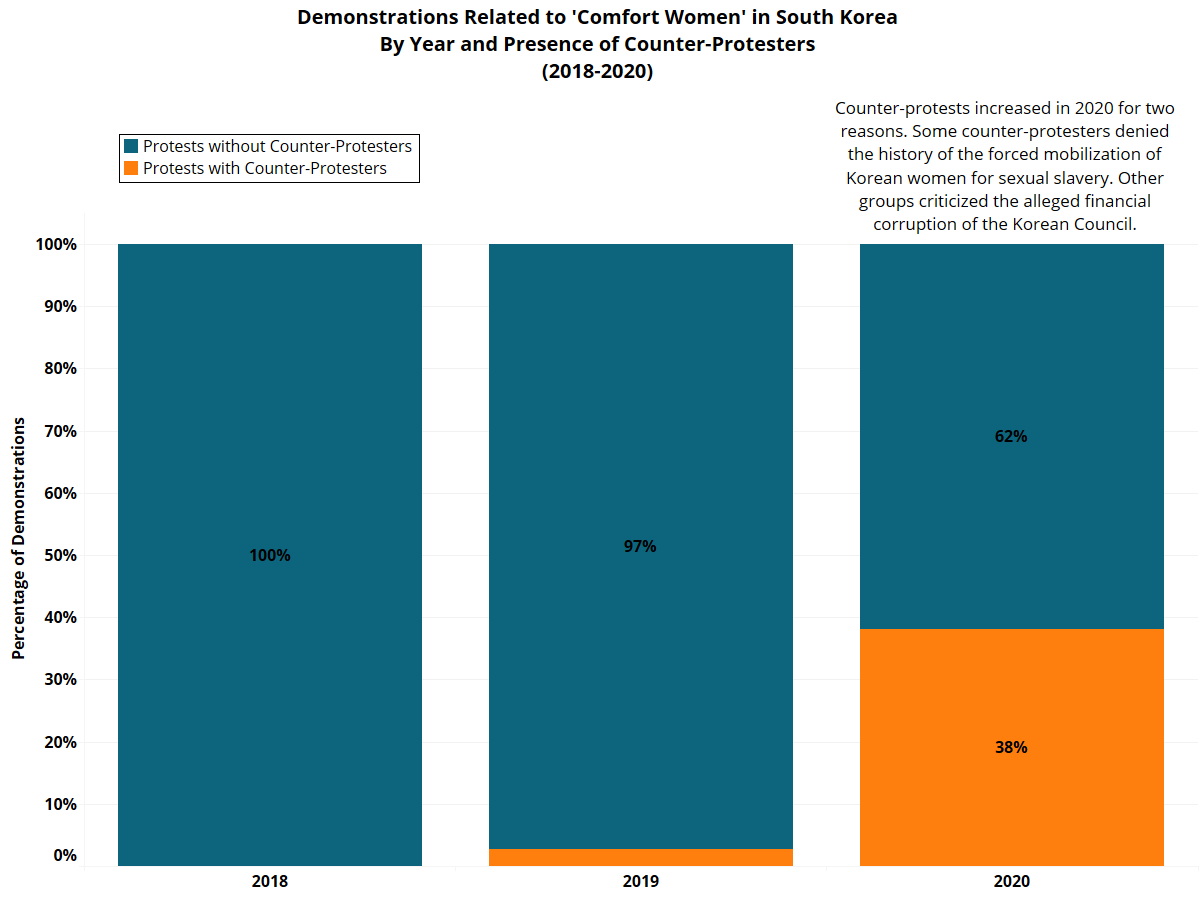

As demonstrations over the ‘comfort women’ issue have risen, leading more people to become interested in and educated on the subject, counter-protest groups have emerged. Counter-protesters increased their activity in 2020 relative to the year prior. While in 2018 and 2019 there were more one-sided demonstrations, over a third of demonstrations were met by counter-protests in 2020 (see graph below).

The counter-protesters can be categorized into two groups based on their demands. The first are comprised of far-right groups who deny the history of the forced mobilization of Korean women to provide sexual services (Hankyoreh, 21 May 2020). They claim that ‘comfort women’ participated in the system voluntarily (Nikkei Asia, 26 December 2019). The publication in mid-2019 of the book Anti-Japan Tribalism co-authored by Lee Woo-yeon, a research fellow at the Naksungdae Institute of Economic Research, caused strong reactions from both pro- and anti-Japanese groups (Nikkei Asia, 26 December 2019). The book challenged some of the widely agreed upon interpretations by South Koreans of Japan’s colonial rule. Lee started to protest against the weekly ‘comfort women’ demonstrations in December 2019. Also, from late-December 2019, two groups — the Joint Action Committee for Investigating Anti-Japanese Statues, and the Korean Modern and Contemporary History Research Council — started organizing demonstrations next to the Wednesday demonstrations, demanding that the Wednesday demonstrations stop and that the Statue of Peace be demolished.1The Statue of Peace, erected in front of the Japanese Embassy in Seoul in 2011, is a symbol representing the women who were coerced to provide sexual services during World War II.

Meanwhile, other groups of counter-protesters have criticized the alleged financial corruption of the Korean Council. Allegations that the Korean Council exploited the surviving victims and misappropriated donations sparked another wave of counter-protests in May 2020 (The Korea Herald, 20 May 2020). The Prosecutor-General ordered an investigation into the Korean Council’s affairs following the allegations (Hankyoreh, 26 May 2020). The Korean Council’s former head, a current member of the Korea’s National Assembly, was indicted in September 2020 on charges including fraud, embezzlement, and breach of trust (Reuters, 14 September 2020), and is still on trial as of March 2021. Nevertheless, the event negatively impacted the image of the organization and has contributed to a rise in counter-protests against the movement. Politically conservative groups — such as People’s Solidarity of Liberty, Freedom Korea National Defense Corps, and Platoon of Moms — which are rarely seen at the demonstration sites for ‘comfort women’ issues, protested against the Korean Council’s alleged corruption scandal on top of existing demands.

Despite the increasing number of counter-protests in 2020, the ‘comfort women’ protest movement has not been undermined. This is largely a result of the proliferation of the national and global advocacy movement for the ‘comfort women’ issue. When the Korean Council was publicly denounced by the alleged embezzlement of public donations, students and civil solidarity groups continued to show support by attending weekly demonstrations organized by the Korean Council (Hankyoreh, 24 May 2020; Hankyoreh, 21 May 2020). The global advocacy movement’s fight to keep the Statue of Peace also helped to call people’s attention back to resolving the ‘comfort women’ issue (The Korea Herald, 14 December 2021).

‘Comfort Women’ Demonstrations amid Growing Anti-Japan Sentiment

The number of attendees of ‘comfort women’ demonstrations skyrocketed in 2019 alongside the general public’s increasing anti-Japan sentiment. In August 2019, the Japanese government implemented a decision to remove South Korea from the ‘white list’ for preferential trading (Xinhua, 28 August 2019). With rising trade and diplomatic tensions between South Korea and Japan, the South Korean public began to protest against Japan’s economic retaliation, initiating a nationwide boycott of Japanese products. These large-scale anti-Japan rallies were not limited to demonstrating solely against Japan’s economic policy, but they also invoked unresolved history between the two countries.

As a result, there was a surge in the number of protesters attending ‘comfort women’ demonstrations and the number of anti-Japan rallies in August 2019 specifically. While the number of protesters participating in the ‘comfort women’ events is typically in the hundreds or fewer, the number spiked to tens of thousands during this time period (AP, 3 August 2019; Yonhap News Agency, 7 August 2019; TBS, 14 August 2019). Protesters demand that Japan express a sincere apology for past atrocities during Japanese colonial rule, including for the ‘comfort women’.

Conclusion

As the main driver of the movement, the Korean Council has pushed forward with continued demonstrations and has maintained deep-rooted support across the country, despite corruption allegations levied against its former leadership. Simultaneously, the public’s widespread anti-Japan sentiment amid worsening bilateral relations between South Korea and Japan has spurred many to participate in the movement.

In early 2021, a South Korean court ruled that the Japanese government should compensate Korean women who were forced to provide sexual services before and during World War II. However, the Japanese government has rejected the ruling, claiming that the situation has already been “resolved completely and definitely” (South China Morning Post, 8 January 2021). Recently, South Korean President Moon Jae-in stated that his administration “is ready to sit down and have talks with the Japanese government anytime” to solve longstanding historical disagreements (The Korea Herald, 1 March 2021). However, tensions persist between the two countries and, when they heighten, the ‘comfort women’ issue rise to the forefront. These demonstrations are expected to spike in line with increased tensions between the two countries going forward. Despite challenges faced by the actors leading the movement, the issue remains deeply entrenched across the country and among a diversity of groups in Korean society. As long as a meaningful resolution is not achieved to address such deep-seated grievances echoing from the horrors of World War II, the movement is likely to continue.

한국의 ‘위안부’ 집회에 대한 다섯 가지 이해: 2018-2020

위안부 집회의 시위대는 1992년 1월부터 매주 수요일마다 주한 전 일본 대사관 앞에 모였다. 그들은 제2차 세계 대전 전후 일본 정부에 의해 자행된 종군 위안부 운영에 관한 공식적 사과를 촉구해왔다 (The Korean Council, 2021). 살아남은 피해자들과 그들의 지지자들은 ‘위안부’를 대상으로 한 성폭력에 대한 정당한 결의안을 옹호한다. 그들에 따르면, 위안부 여성들은 전후 기간 일본 장교와 군인들에게 ‘성’을 제공하도록 강요당했다 (Asian Women’s Fund, 2021). 한국에서 가장 오래 지속되고 있는 시위 중 하나인 위안부 집회는 시간이 흐름에 따라 더 많은 지지를 얻고 있고, 지리적으로도 시위의 범주가 확장되는 경향을 보이고 있다. 수많은 난관에도 불구하고 집회는 한일 관계의 지표 역할을 해왔다. 이 보고서는 2018년 1월부터 2020년 12월까지의 시위를 5가지 방향, 정의기억연대 (정의연)의 주체적 역할, 다양한 주체의 시위 참여, 시위의 지리적 확산, 반대 시위의 증가, 그리고 반일 감정 확산의 맥락에서 분석하려 한다. 위안부 문제가 해결될 기미가 보이지 않음에도 불구하고, 집회는 거의 30년 동안 지속되었다. 하지만 한국 사회 전반의 지지를 받고 있는 시위는, 한일관계의 긴장 속 반대 시위에 대한 회복력을 보이며, 꾸준히 지속될 것으로 보인다.

정의연의 주체적 역할

첫 평화로운 시위가 1992년에 서울에서 열린 이후, 정의연은 29년이 넘는 세월 동안 수요집회를 주최해왔다 (The Korean Council, 2021). Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED)의 2018년 1월부터 2020년 12월 말까지의 데이터에 따르면, 정의연은 전국 위안부 관련 집회의 약 69%에 해당하는 161회의 시위에 참여했다. 이러한 집회는 주로 다음 주제들에 중점을 둔다: 일본 정부의 공식적인 사과 요구, 위안부 문제 해결에 관한 한국 정부의 수동적이고 회피적인 태도 비판, 그리고 특정 교수, 역사가, 보수적 시민단체에 의해 추진되는 수정주의 역사에 대한 비판. 정의연은 매주 열리는 수요집회를 통해 위안부 문제에 대한 인식을 높여왔다. 이를 통해 다른 시민단체들이 행사를 주최, 후원 및 참석하게 하여 운동과 연대하도록 유도하기도 했으며, 위안부 시위에서 중추적 역할을 담당하게 되었다.

다양한 주체의 시위 참여

정의연이 위안부 집회를 조직하는데 앞장서 왔지만, 다양한 사회단체와 일반 대중도 피해자에 대한 정의를 옹호했다. 특히 2018년부터 2020년까지 총 80개의 시위 이벤트에 (전체 위안부 관련 시위의 34%) 학생들이 참석했다. 초중고 학생부터 대학생에 이르기까지, 학생들은 다른 주체들이 주최하는 시위에 참석하거나 본인들이 시위를 조직하기도 했다. 젊은 세대가 운동에 적극적으로 참여하는 것은, 위안부 문제가 해결되지 않는 이상, 이 시위가 다음 세대에서도 지속될 수 있음을 시사한다.

또한 정치인, 종교 단체, 노동 단체 및 기타 시민 사회 단체들도 위안부 집회를 조직하고 참석했다. 한국과 같은 역사를 공유하는 필리핀과 같은 나라에서 살아남은 피해자와 그 가족들도 시위에 적극적으로 참여하는 모습을 보였다. 중국, 일본, 인도네시아, 미국, 영국에서 온 시위대가 시위에 참여했고, 위안부 문제에 지지를 표명했다. 수많은 그룹에서 참여한 다양한 결의 지지자들은 더 넓은 지지기반을 동원해내는 집회의 가능성을 보여준다. 이는 국제적 지원과 함께 집회의 장기적 지속 가능성을 드러낸다.

시위의 지리적 확산: 전국적 시위

위안부 집회는 전국적으로 열렸고, 수많은 지역활동가들도 시위에 참여했다. 집회의 대부분은 서울에서 개최되었지만, 약 20%는 서울 외의 지역에서 조직되었으며 다양한 지역에서 정기적으로 보고되었다 (아래 지도 참조). 여성 단체, 인권 단체, 노동 단체, 서울 외 지역의 시민 단체들이 이러한 집회를 조직하는 데 적극적으로 참여해왔다. 예를 들어, 약 10개의 지역 여성단체로 구성된 부산 여성 행동은 2016년 1월부터 매월 마지막 수요일 부산에 있는 일본 영사관 앞에서 수요 집회를 열고 있다. 이러한 시위의 지리적 범위는 위안부 문제가 한국 사회 전반에 얼마나 깊고 널리 퍼져 있는지를 보여주는 또 다른 예이다.

반대 시위의 증가: 반 위안부-정의연 집회 (반대 집회)의 출현

위안부 문제에 대한 집회가 증가하면서 더 많은 이들이 주제에 관심을 두게 되었고, 이에 따라 집회에 반대하는 집단들 또한 등장했다. 반대 집회 시위대는 2020년에 활동이 증가했다. 2018년과 2019년에는 일방적 (반일) 위안부 집회가 대부분이었지만, 2020년 집회의 1/3 이상에 반대 집회가 펼쳐졌다 (아래 그래프 참조).

일본을 규탄하며 위안부 문제 해결을 요구하는 집회가 전국에서 일어나는 동안 (위 그래프 참조), 반대 집회들은 모두 서울에서만 보고되었다. 위안부 집회는 다양한 사회 집단의 지지를 받았지만, 반대 집회는 지지자의 다양성이 제한적인 것으로 보이며 주로 보수 집단과 연계된 활동가들이 주도했다. 이러한 사실은 집회의 제한된 지리적 확산과 지원 기반을 나타내며, 반대 집회의 성공 가능성을 더욱 제한하고 있다.

반대 집회의 참가자들은 요구에 따라 두 그룹으로 나눌 수 있다. 첫 번째는 위안부의 역사를 부정하는 극우 단체들이다 (Hankyoreh, 21 May 2020). 그들은 위안부가 자발적으로 매매춘에 참여했다고 주장한다 (Nikkei Asia, 26 December 2019). 낙성대경제연구소 이사장인 이영훈 등이 공동 집필한 반일 종족주의는 2019년 중반에 출판되며 친일 반일 그룹의 강한 반응을 불러일으켰다 (Nikkei Asia, 26 December 2019). 이 책은 일본의 식민 통치에 대한 한국인들의 이해에 전면적으로 도전했다. 책의 공저자들은 2019년 12월부터 반대 집회를 열기 시작했다. 또한, 2019년 말에는 반일 동상 진실 규명 공동 대책 위원회와 한국 근현대사 연구회가 조직되어 수요 집회 옆에서 반대 집회를 열기 시작했다. 그들은 반대 집회를 통해 수요 집회를 중단하고 평화의 소녀상을 철거할 것을 요구했다.

한편 다른 반대 집회의 시위자들은 정의연의 후원금 유용 의혹을 비판했다. 정의연이 살아남은 위안부 피해자들을 착취하고 후원금을 유용했다는 주장은 2020년 5월 또 다른 반대 집회의 물결을 촉발했다 (The Korea Herald, 20 May 2020). 검찰은 혐의에 따라 정의연의 업무에 대한 수사를 명령했다 (Hankyoreh, 26 May 2020). 정의연의 전 대표이자 더불어민주당의 국회의원으로 당선된 윤미향은 2020년 9월 사기, 횡령 등 혐의로 기소되었으며 (Reuters, 14 September 2020), 2020년 11월 재판이 시작되었다. 이 일련의 사건은 정의연의 이미지에 부정적 영향을 미쳤고, 반대 집회의 자양분이 되었다. 위안부 관련 시위에서 전혀 볼 수 없었던 자유 연대, 자유대한호국단, 엄마부대와 같은 보수단체들이 정의연의 부패 스캔들에 항의하며 반대 집회의 정면에 나섰다.

2020년에 정점을 찍은 반대 집회의 등장에도 불가하고 위안부 집회의 불씨는 사그라지지 않았다. 이는 주로 위안부 문제에 대한 전국적 및 세계적인 우호 여론이 확산된 결과이다. 후원금 유용 혐의로 정의연이 공개적 비난을 받았을 때, 학생들과 시민 단체들은 정의연의 수요 집회에 참석해 지속적인 지지를 보냈다 (Hankyoreh, 24 May 2020; Hankyoreh, 21 May 2020). 평화의 소녀상을 지키기 위한 세계 각국 활동가들의 지지와 지원도 위안부 문제 해결에 다시 사람들의 관심을 불러일으켰다 (The Korea Herald, 14 December 2021).

반일 감정 확산: 반일 감정 확산에서의 위안부 집회

2019년 위안부 집회의 참석자 수는 일반 대중의 반일 감정 확산과 함께 급증했다. 2019년 8월 일본 정부는 한국을 수출 과정에서 우대해주는 화이트 리스트에서 제외하기로 결정했다 (Xinhua, 28 August 2019). 한일간 무역과 외교적 긴장이 고조되었고, 한국 국민들은 일본의 경제적 보복에 항의하며 일본 제품에 대한 전국적인 불매운동을 시작했다. 이러한 대규모 반일 집회는 오로지 일본의 경제 보복에 대한 시위에만 국한된 것이 아니라 양국 간의 해결되지 않은 역사에서 촉발되었다.

그 결과 2019년 8월 위안부 집회와 반대 집회가 급증했다. 위안부 집회에 참여하는 시위자의 수는 일반적으로 수백 명 이하였지만, 이 기간엔 수만 명으로 급증하는 경향을 보였다 (AP, 3 August 2019; Yonhap News Agency, 7 August 2019; TBS, 14 August 2019). 집회 참여자들은 일본이 위안부 문제를 포함해 일제 식민지 시대의 잔혹한 행위들에 대해 진심으로 사과할 것을 요구했다.

결론

정의연은 전 지도부의 부패 혐의에도 불구하고, 지속적인 집회를 통해 위안부 집회의 주된 동인으로서 전국적인 지지를 받아왔다. 동시에 한일 양국 관계가 악화되고 있는 가운데 대중의 반일 정서가 확산되면서 많은 사람들이 위안부 집회에 참여하게 되었다.

2021년 초, 한국 법원은 일본 정부가 위안부에게 보상해야 한다는 판결을 내렸다. 그러나 일본 정부는 상황이 이미 ‘완전하고 확실하게 해결되었다’며 보상을 거부했다 (South China Morning Post, 8 January 2021). 이 상황에도 불구하고 최근 문재인 대통령은 오랜 역사의 불화를 해결하기 위해 ‘언제든지 일본 정부와 대화를 나눌 준비가 되어있다’고 밝혔다 (The Korea Herald, 1 March 2021). 그러나 양국 간 긴장감이 고조되면서 위안부 문제가 또다시 대두되고 있다. 이러한 시위는 앞으로 양국 간의 긴장이 고조됨에 따라 급증할 것으로 예상된다. 운동을 주도하는 주체들이 직면한 도전에도 불구하고, 이 문제는 전국적으로, 그리고 한국 사회의 다양한 집단들 사이에서 깊숙이 자리 잡고 있다. 제2차 세계 대전의 잔상에서 울려 퍼지는 이러한 깊은 비극의 분쟁이 해결되지 않는 한, 위안부 집회는 계속될 것이다.