Somalia’s parliamentary and presidential elections are set to take place amidst a general climate of political tensions and violence. A constitutional crisis stoked by months of political deadlock between President Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed ‘Farmaajo’ and the opposition threatens to escalate into a violent conflict pitting federal forces against state-based militias, as well as armed clans with competing loyalties. Across the country, signs of increasing unrest have surfaced in Somalia’s federal states of Jubaland, Galmudug, and Hirshabelle, exposing the risk of a violent turn in Somalia’s political crisis.

Initially scheduled to begin in November 2020, parliamentary elections were postponed to 2021, violating the electoral timeline agreed by Farmaajo and the state presidents. With Farmaajo’s mandate expiring in February 2021 and the government failing to announce a definitive election date, the opposition now questions the legitimacy of the incumbent president ruling beyond the end of his term. Opposition leaders, including some of the state presidents such as Jubaland’s Ahmed Madobe and Puntland’s Said Abdullahi Dani, have also accused Farmaajo of manipulating local elections and staffing electoral commissions with his allies.

Across the country, these political tensions have occasionally escalated into violence. Government troops clashed with security forces affiliated with local elites in both Jubaland and Puntland, as well as in Galmudug. There are also frequent episodes of turmoil involving clans and communal groups. This is against the backdrop of the ongoing insurgency by Al Shabaab, which continues to exercise its control over large swathes of central and southern Somalia after more than a decade of civil war. The turbulent run-up to the general elections, and a contested aftermath, may provide yet another opportunity for Al Shabaab to step up its challenge to the Somali government and the ill-equipped Somali National Army (SNA).

This report draws on ACLED data to provide a general overview of election-related conflict risks in Somalia. In particular, it intends to show how ongoing tensions over the upcoming general elections have resulted in violence at the local level, involving an array of state and non-state armed groups. The focus is especially on Somalia’s federal states, which constitute distinct, yet interlocking, political environments. The report further examines different post-electoral scenarios, and how these could impact Somalia’s stability.

A Fragile Political Order

At the heart of Somalia’s instability lies a political order ridden by tensions between the central government and the federal member states of Galmudug, Hirshabelle, Jubaland, Puntland, and South West (Somaliland is a de facto independent country with limited international recognition). Since the inception of the Federal Government of Somalia in 2012, disputes have arisen over the devolution of power and the allocation of resources from the central government to the federal states. Among the states that have consistently been at odds with Mogadishu are Jubaland and Puntland. Both have long demanded greater autonomy from the center, occasionally seeking support from neighboring and regional countries and provoking backlash from the federal government. Puntland has claimed rights over offshore oil explorations, which Mogadishu claims fall under its sovereignty. Maritime border demarcation has also sparked disputes between Puntland and Somaliland, and between Somalia and Kenya.1As of April 2021, hearings over the maritime boundary dispute between Kenya and Somalia are being held at the International Court of Justice (ICJ).

The country’s political system traces its origins to the 2000 Somalia National Peace Conference held in Arta, Djibouti, which was meant to restore peace among clan-affiliated warlords. The conference established a 4.5 power-sharing system regulating the institutional representation of Somalia’s major clans. The formula prescribes that parliamentary seats are allocated at the state level and shared equally among the four main clans (Hawiye, Darod, Dir, and Rahanweyn). Half of the seats assigned to each major clan are reserved for minority groups (Menkhaus, 2007) (see Annex 1).

The influence that each clan and sub-clan exercises varies from state to state. The influential Hawiye sub-clans are prevalent in Hirshabelle, Galmudug, and the capital Mogadishu, while the Rahanweyn families (also known as Digil-Mirifle) dominate the South West. Darod sub-clans are spread across Puntland and Jubaland states. The Isaaq and Dir dominate the self-declared state of Somaliland. Instead of consolidating state institutions, the power-sharing system exacerbated the competition between Somali clans, often spiralling into retaliatory violence to avenge previous killings.

Tensions surfaced yet again in the run-up to the 2020 elections. What stoked the dispute between President Farmaajo and the opposition was the signing of a new electoral law in February, which replaced the existing indirect voting system with universal suffrage as requested by Western donors (International Crisis Group, 10 November 2020). In accordance with the 4.5 power-sharing system, delegates from the clans select the 275 members of the Lower House while federal state assemblies elect the 54 senators of the Upper House. The two houses jointly elect the president. Hence, clan elders and federal states retain considerable power under this system, and have long resisted reforming the electoral law. The opposition instead accused Farmaajo of using the electoral bill as a means to delay the vote and extend his term, while also interfering with local elections to install loyalists of the president at the helm of the states.

An agreement outlining the electoral process was brokered in September 2020. The deal introduced some changes to the process but, crucially, maintained the indirect voting system (Somalia Dialogue Platform & Somali Public Agenda, December 2020). Despite initial hopes to move ahead with the parliamentary elections in December, both the government and the federal states missed the deadlines to form federal and regional electoral commissions, select the delegates, and eventually hold the ballot. In December, President Farmaajo escalated a dispute with Kenya, severing diplomatic ties and accusing Somalia’s southern neighbor of inciting sedition in Jubaland. Seen as yet another attempt to delay the vote by stoking nationalist sentiments, opposition leaders announced in February they would no longer recognize the incumbent after his term expired and “demand a peaceful transfer of power” (Al Jazeera, 8 February 2021).

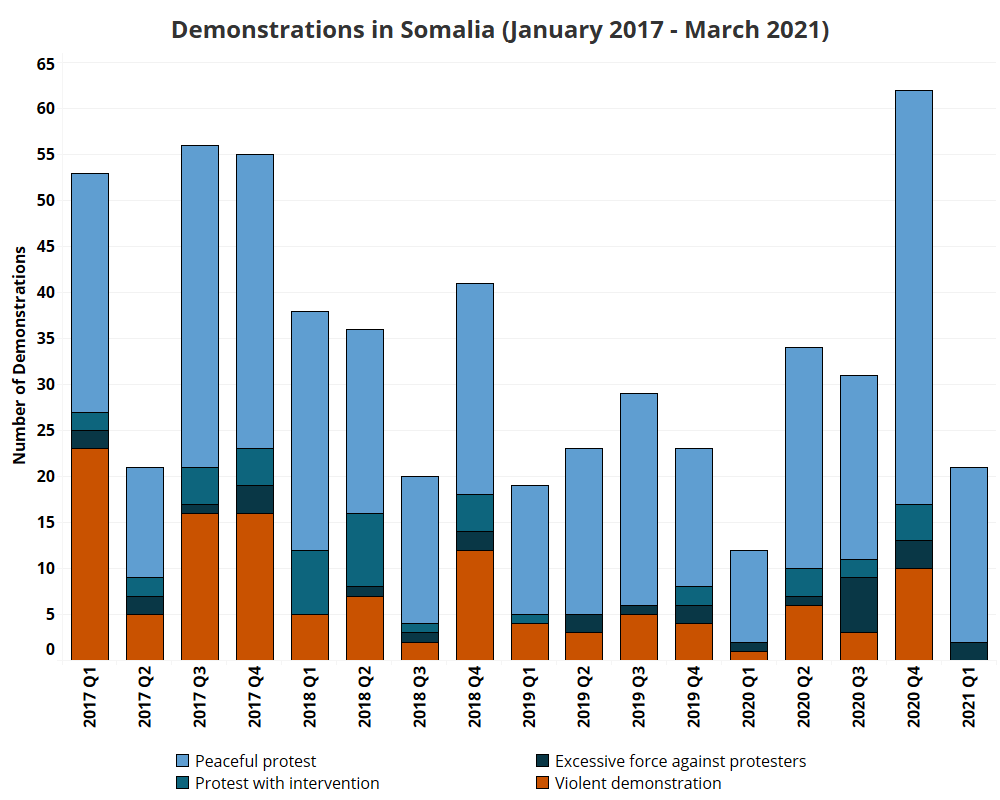

Reflective of election-related tensions, demonstrations were held across Somalia in 2020 and in early 2021 despite government-imposed restrictions to contain the spread of coronavirus (see figure below). There are already signs that, in a context of heightened electoral mobilization, demonstrations could become violent. Street clashes erupted in Mogadishu on 19 February 2021 after Somali government troops shot into the crowd at a peaceful demonstration attended by opposition leaders, including presidential candidate and former Prime Minister Hassan Ali Khaire. Security forces exchanged gunfire with armed opposition supporters, which reportedly included soldiers hailing from opposition-friendly clans (Reuters, 19 February 2021).

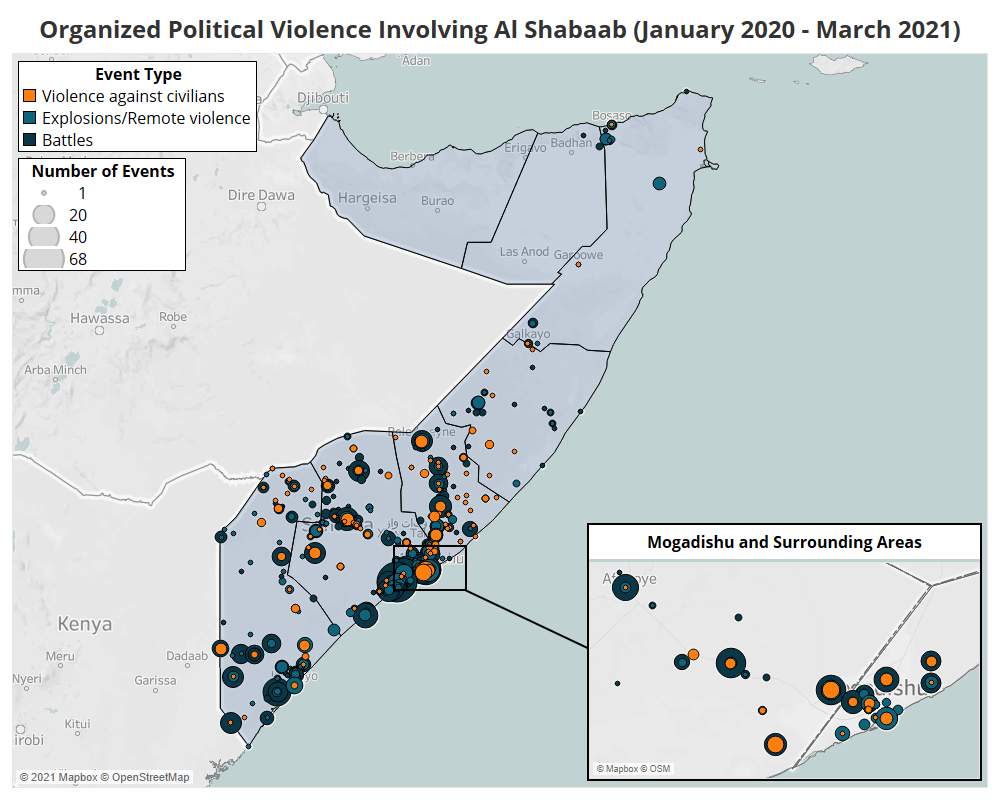

This political turbulence has negatively affected the government’s response to the Al Shabaab insurgency. In 2020, Al Shabaab continued to conduct high-profile attacks against government forces and international troops across much of central and southern Somalia (see figure below). Occasional setbacks, such as government forces retaking the town of Janaale in March (Garowe Online, 17 March 2020), did not prevent the militant group from reorganizing to prevent defections, establishing new makeshift training camps, and conducting attacks on Mogadishu (United Nations Security Council, 13 August 2020: 3). With the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, Al Shabaab has also engaged in service delivery activities in the territories under its control, providing basic goods to the local population and boosting its recruitment strategy (UNSC, 3 February 2021: 11). Over a decade since the start of the insurgency, Al Shabaab is estimated to collect nearly as much tax as the Somali government according to a recent report (Hiraal Institute, October 2020).

Political Violence in Somalia’s Federal States

Ahead of the February 2017 elections, Somalia experienced considerable violence. Over 1,100 civilians were reported killed across the country between February 2016 and January 2017, while the number of overall fatalities in 2016 was the second highest over the past decade after 2017. During the current pre-electoral period (February 2020 – January 2021), conflict-related civilian fatalities decreased by roughly one third, yet electoral disputes continue to fuel instability across the country.

Jubaland

Jubaland has long been a hotbed of clan-related disputes. The current state capital and Somalia’s second-largest port, Kismayo, was contested between Somalia’s major clans until 1994, when the Darod wrested control of the city from the Hawiye. Since then, Darod sub-clans including the Ogaden, the Majerteen and the Marehan have competed to control the region now falling under the authority of the Jubaland state administration.2The Somali Patriotic Movement led by General Aden Abdullahi Nur Gabyow (Ogaden) and General Mohamed Siad Hersi ‘Morgan’ (Majerteen) controlled Kismayo from 1994 to 1999. Between 1999 and 2006, Kismayo fell under the authority of the Juba Valley Alliance led by Colonel Barre Adan Shire Hiiraale (Marehan). The Marehan, the Ogaden, and the Majerteen continued to alternatively rule over the city until 2009, when Al Shabaab took over Kismayo. The Raskamboni Movement commanded by Ahmed Madobe from the Ogaden clan eventually recaptured the city in 2012.

Jubaland President Ahmed Mohamed Islam, also known as Ahmed Madobe, has emerged as a prominent figure in the opposition against Farmaajo. Madobe led Kenya-backed Somali militias to retake Kismayo in 2012, before being elected Jubaland president in 2015 (Reuters, 22 August 2019). Madobe and Farmaajo, who hail from the Ogaden and the Marehan clans of the Darod respectively, parted ways in 2019, when the incumbent president defeated the candidate backed by Mogadishu in the Jubaland state elections (The East African, 9 December 2019). Opposition candidates who were barred from running held a separate election process in Kismayo, electing Abdirashid Mohamed Hidig. The federal government rejected both outcomes.

The government retaliated against the Jubaland state administration, requiring flights from and to Kismayo to stop in Mogadishu. In August 2019, Jubaland security minister Abdirashid Hassan Abdinur, also known as Abdirashid Janan, was arrested in Mogadishu’s Aden Adde International Airport on charges of serious human rights violations in Jubaland’s Gedo region (Radio Dalsan, 2 September 2019). Months later, the central government’s decision to deploy 700 SNA troops in Gedo, a Marehan-majority region and a stronghold of President Farmaajo, sparked new tensions between Mogadishu and Kismayo (Garowe Online, 25 February 2020). The standoff escalated in late February 2020, when Janan escaped from a detention center in Mogadishu seeking refuge in Kenya. As a result, the Somali government accused Kenya, which sees Jubaland key to its domestic security, of providing shelter to Janan and undermining Somalia’s stability. This event precluded Somalia’s decision to expel the Kenyan ambassador in November and suspend diplomatic relations with Kenya in December, months before the ICJ was called to adjudicate on the maritime boundary dispute (New York Times, 15 December 2020).

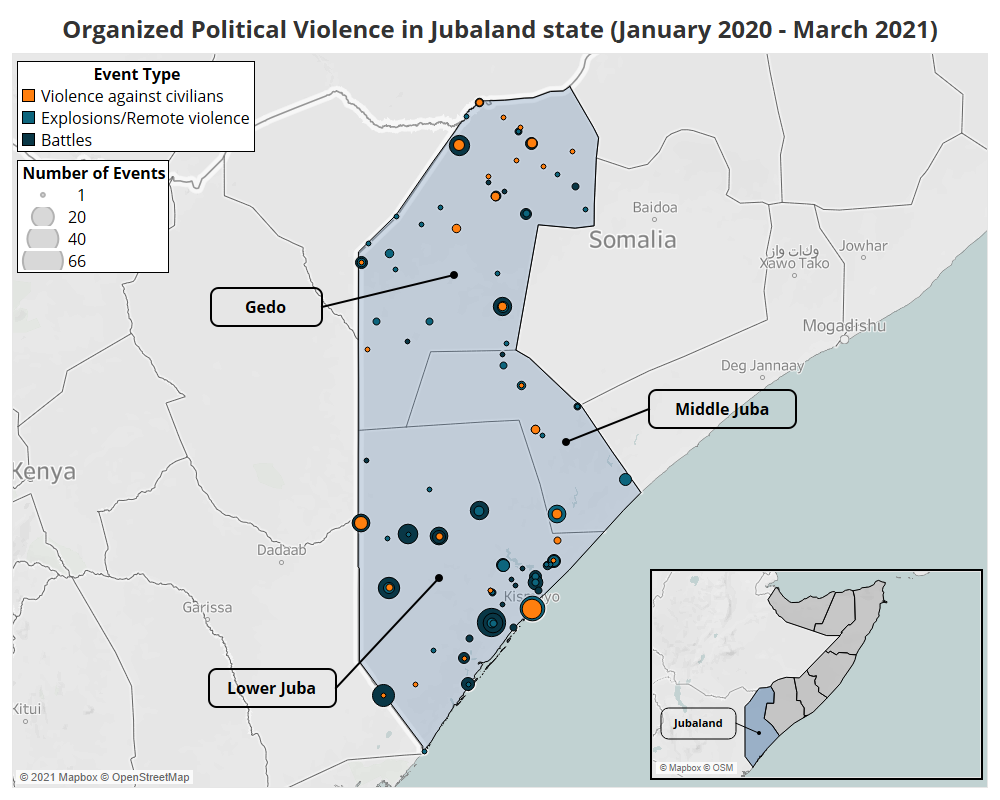

The tug-of-war between Mogadishu and the Jubaland administration has had major implications for the local conflict environment (see figure below). Notably, it diverted efforts from the fight against Al Shabaab. The militants control several districts across the state, while Kismayo and neighboring areas are under the control of the local government. In the days following Janan’s jailbreak, clan-based clashes claimed the lives of around 20 people outside Kismayo (Garowe Online, 5 February 2020). Since February 2020, battles between forces loyal to the Somali federal government and those loyal to Jubaland security minister have occasionally erupted in the border town of Belet Xaawo in Gedo region (Garowe Online, 2 March 2020). In January 2021, the latest round of heavy fighting in Belet Xaawo resulted in 11 people reportedly killed, including nine civilians caught in the crossfire, and several others displaced (Hiiraan, 25 January 2021).

Galmudug, Hirshabelle, and South West

The central government’s attempt to interfere in regional affairs has also sparked unrest across central Somalia. Notably, heavy clashes erupted in the aftermath of a contested election in Galmudug state in February 2020. The state parliamentary assembly elected Ahmed Abdi Kariye, a former minister close to the federal government, president of the state. His nomination faced the resistance of Ahlu Sunna Wal Jamaa (ASWJ), an Ethiopia and United States-backed Sufi group whose fighters were integrated into the local security apparatus after battling with Al Shabaab in Galmudug (Ingiriis, 16 June 2020). ASWJ leader Sheikh Mohamed Shakir rejected the election results and declared himself president.

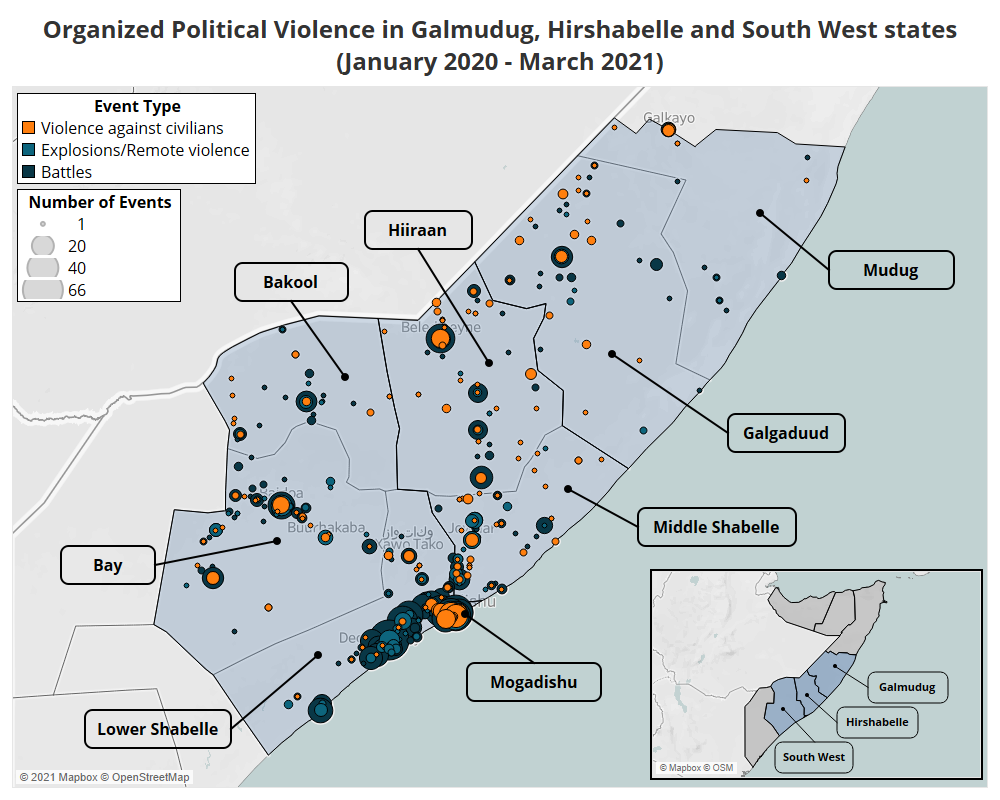

Weeks later, clashes between government forces and ASWJ fighters broke out in Galmudug’s capital Dhusamareb and neighboring villages, ending when Shakir surrendered to the security forces (VOA News, 29 February 2020). Especially in the Galgaduud region, clan-based violence over political grievances and revenge killings involved families affiliated with the Darod and Hawiye, spurring a resurgence of Al Shabaab activity unseen in the region since 2016 (see figure below). Clashes were particularly heavy between the Ayr, Saleban, and Marehan sub-clans following disputes over land and the allocation of seats (Radio Dalsan, 7 September 2020).

Hirshabelle state also became a battleground in the ongoing struggle between the central government and the federal states. In November 2020, candidates backed by Mogadishu were elected respectively speaker and deputy speaker of the state parliamentary assembly, drawing fresh accusations of government interference in state polls (Garowe Online, 5 November 2020). State parliamentary assemblies are tasked with overseeing the federal senatorial ballots.

A few days later, Ali Abdullahi Hussein, also known as Ali Gudlawe, was voted in as Hirshabelle’s new president (Somali Guardian, 11 November 2020). His election allegedly violated a power-sharing agreement regulating access to state offices, sparking new tensions between clans in Hiiraan (Somali Public Agenda, 10 October 2020). Demonstrations erupted in Beledweyne, capital of the Hiiraan region and home to the Hawadle and Gaal-jecel clans, against the newly elected Hirshabelle administration and in support of secessionist General Abukar Haji Warsame (General Xuud) (Hiiraan Online, 30 November 2020). General Xuud’s militia clashed with local security forces near Beledweyne and Ceel Gaal, with Al Shabaab militants taking advantage of the situation to make new advances (see figure above).

The South West state experienced less election-related volatility than other Somali states. Yet, it remains a hotbed of Al Shabaab insurgency and Somalia’s most violent state, both in terms of recorded violent events and reported fatalities (see figure above). Over 40 percent of conflict-related fatalities recorded nationwide in 2020 were reported in the South West. Lower Shabelle, the region surrounding the capital Mogadishu, accounted for over two thirds of all violence recorded in the state, and over one fourth nationwide.

Puntland

The Puntland administration is a leading member of the opposition to Farmaajo. Its president, Said Abdullahi Dani, lost to Farmaajo in the 2017 presidential elections, and has sided with President Madobe of Jubaland to challenge the incumbent. Dani and Madobe hail from the Majerteen and Ogaden clans of the Darod, which have long been at loggerheads with Farmaajo’s Marehan clan.

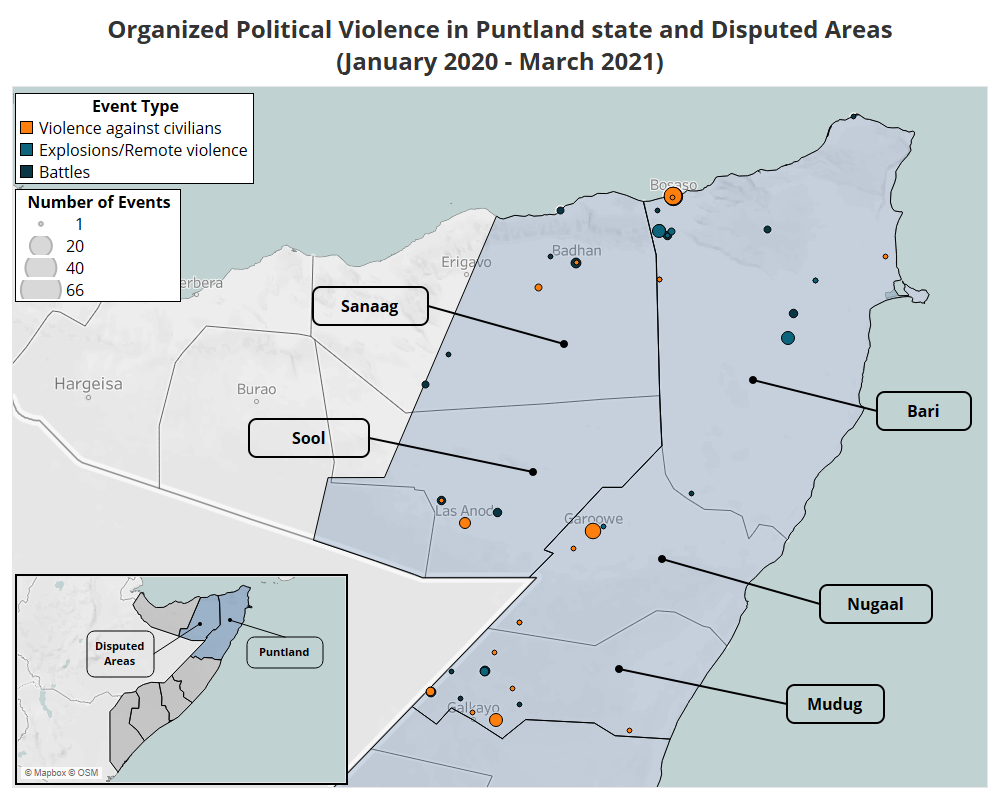

In the semi-autonomous region, security forces are grappling with multiple challenges from Islamic State militants active in the northern mountainous areas of Bari region and Al Shabaab (see figure below). In 2020, Al Shabaab conducted high-profile attacks against government institutions. These included the assassinations of the governors of Nugal and Mudug regions in two suicide vehicle-borne improvised explosive device (SVBIED) attacks in March and May 2020 (Garowe Online, 17 May 2020), and more recently, a deadly jailbreak in Bosaso where the group freed approximately 400 inmates (Reuters, 5 March 2021).

Separately, the territorial dispute with the breakaway state of Somaliland over the contested Sool and Sanaag areas turned violent at the beginning of the year when local security forces clashed in Ceerigaabo and Laasqoray (Wargane, 25 February 2020).

Scenarios for the Somali General Elections

Somalia’s general elections were to begin in late 2020. Controversies between the central government and the federal states resulted in postponing the election date, with plans currently underway to ensure elections are held by the end of 2021. In March, international partners including the United States, the United Kingdom, the European Union, and Turkey, expressed concerns over the months-long political impasse (Garowe Online, 20 March 2021, 27 March 2021; European Union External Action Service, 23 March 2021; Anadolu Agency, 24 March 2021). Negotiations are ongoing between the incumbent and the opposition to allow for a peaceful transition of power, yet tensions remain high and there is a risk of a violent escalation of the electoral crisis. Below are three main sources of tensions in the current electoral phase.

Clan Rivalries

The Hawiye and Darod clans are likely to play a key role in deciding Somalia’s next president and ensuring a peaceful resolution to the crisis. These two clans have long competed over who should assume the presidency, in addition to other long-standing rivalries over access to resources, ideologies, and political representation in national and local parliaments. They dominate the parliamentary assemblies in four states, with the Darod prevalent in Jubaland and Puntland and the Hawiye in Hirshabelle and Galmudug (the Rahanweyn are the majority in the South West state). Additionally, fierce competition within the Darod, between the Marehan clan aligned with Farmaajo and the Ogaden and Majerteen close to the Jubaland and Puntland state administrations, threatens to further intensify.

There are concerns that the Darod — and especially the current president — would not renounce the presidency easily, possibly sparking inter-clan disputes similar to those that preceded the 1991 civil war (Roble, 8 November 2013). Reports have recently emerged suggesting that the central government plans to create a new state merging Gedo and Bakool regions to weaken the opposition and consolidate a support base prior to the elections (Halgan Media, 4 April 2021). If confirmed, this is likely to further exacerbate tensions between the clans. At the state level, mobilization along clan lines occasionally occurred around contested local elections in 2020, and could therefore escalate in the event of a contested federal vote.

Farmaajo’s Re-election

The outgoing president is currently seeking an unprecedented re-election. In fact, no Somali president since 2009 has ever been re-elected, and Farmaajo’s predecessors, Sharif Sheikh Ahmed and Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, only served one term in office. His attempt to postpone the election has stirred widespread opposition, with several leaders preparing to succeed Farmaajo. It is currently unclear whether he can succeed in getting re-elected. However, a scenario where he wins a second term is likely to face widespread resistaPce, especially among hostile state administrations. In Jubaland, there is a risk that occasional clashes between the SNA and the Jubaland security forces could escalate into a military confrontation benefitting Al Shabaab.

Extension of the President’s Term

A scenario where Farmaajo succeeds in extending his mandate indefinitely risks prolonging the current state of instability. His term ended on 8 February 2021, with the opposition no longer recognizing its legitimacy. A scenario where Farmaajo can extend his term may pave the way for a caretaker unity government, which is yet unlikely to quell tensions. Indeed, a term extension would mark a suspension of constitutional provisions, prolonging instability and likely facing backlash from disgruntled or excluded clans.

International Implications

Somalia’s international partners have worked to support a smooth solution to the electoral impasse (UN Assistance Mission in Somalia, 21 March 2021). Recently, they sponsored talks between the central government, federal states, and opposition leaders in Dhusamareb and Mogadishu to accelerate the implementation of the September electoral agreement. Outgoing President Farmaajo relies on external political and economic support, and a loss of international legitimacy following an escalation of either the domestic crisis or the diplomatic row with Kenya could have major consequences for his political survival.

Conclusion

Over the past year, Somalia has experienced considerable instability linked to the planned parliamentary and presidential elections. President Farmaajo’s attempt to extend his term has encountered fierce resistance from the opposition, including some of the state leaders. A months-long dispute over the electoral law ended with a slightly amended indirect voting system, which leaves power in the hands of state assemblies and clan elders. At the same time, the Somali government was accused of meddling in state elections in order to swing the votes in its favor. Frequent skirmishes broke out in several parts of Somalia between federal and local security forces, as well as between clans with contrasting loyalties and interests. As Somalia comes closer to its electoral reckoning, there is a serious risk of its founding institutions fragmenting along regional and clan lines.

Against this backdrop of intense competition among national and local actors, Al Shabaab is likely to capitalize from further electoral instability. Over 15 years since its emergence, the insurgent group continues to conduct operations against government troops and the African Union peacekeeping forces known as AMISOM, undeterred by the massive counter-insurgency efforts. Regular insurgent attacks on Mogadishu and the group’s tight control over the areas surrounding the capital shows Al Shabaab’s enduring strength vis à vis the government it aims to oust. With Somalia presumably going to the polls in 2021, and AMISOM set to begin transferring security responsibilities to the SNA by the end of the year, Al Shabaab may continue to take advantage of governance vacuums to step up its insurgency.

Annex 1

The following tables display the share of seats accorded to each clan and in each constituency for the upcoming Somali parliamentary elections. The allocation of seats is based on the 4.5 power-sharing system. According to the new electoral law, elections for the lower house will take place in 11 centers across Somalia (two for each federal state), overseen by federal and local election committees (Somalia Dialogue Platform & Somali Public Agenda, December 2020). The parliamentary assemblies of each federal state will instead designate the representatives to serve in the Upper House.

Distribution of seats in the Lower House (275 seats)3Information about the distribution of seats is an elaboration by the authors on the 2017 parliamentary elections (Xog-doon News, 6 February 2017).

| State | Election center | Clan | Sub-clan | Number of seats |

| Puntland | Bosaso | Darod | Warsangeli | 4 |

| Bosaso | Darod | Dishiishee | 2 | |

| Bosaso | Darod | Osman Mohamud | 2 | |

| Bosaso | Darod | Ali Saleban | 1 | |

| Bosaso | Darod | Caali Jibrahiil | 1 | |

| Bosaso | Darod | Carab Salax | 1 | |

| Bosaso | Darod | Leelkase | 1 | |

| Bosaso | Darod | Siwaaqroon | 1 | |

| Bosaso | Darod | Ugar Saleban | 1 | |

| Bosaso | Galgala/Sab | Yibir | 1 | |

| Bosaso | Hawiye | Madhiban | 1 | |

| Garowe | Darod | Dhulbahante | 8 | |

| Garowe | Darod | Leelkase | 4 | |

| Garowe | Darod | Awrtable | 3 | |

| Garowe | Darod | Carab Salax | 2 | |

| Garowe | Darod | Cumar Maxamuud | 2 | |

| Garowe | Darod | Ciise Maxamuud | 1 | |

| Garowe | Darod | Reer Biciidyahan | 1 | |

| Total | 37 | |||

| State | Election center | Clan | Sub-clan | Number of seats |

| Jubaland | Kismayo | Darod | Absame | 10 |

| Kismayo | Dir | Dir | 4 | |

| Kismayo | Darod | Harti | 3 | |

| Kismayo | Bantu/Jareer | Jareer Weeyne | 2 | |

| Kismayo | Ajuuran | Ajuuran | 1 | |

| Kismayo | Bajuun | Bajuun | 1 | |

| Kismayo | Hawiye | Shikhaal | 1 | |

| Kismayo | Hawiye | Galjaceel | 1 | |

| Kismayo | Rahanweyn | Gar-jante | 1 | |

| Kismayo | Rahanweyn | Geelidle | 1 | |

| Kismayo | Rahanweyn | Hubeer | 1 | |

| Kismayo | Rahanweyn | Yaantaar | 1 | |

| Garbaharey | Darod | Mareexan | 10 | |

| Garbaharey | Rahanweyn | Gabaa-weyb | 1 | |

| Garbaharey | Rahanweyn | Gasar-gude | 1 | |

| Garbaharey | Dir | Fiqi-muxumed | 1 | |

| Garbaharey | Dir | Gadsaan | 1 | |

| Garbaharey | Dir | Garre | 1 | |

| Garbaharey | Dir | Macalin Weyne | 1 | |

| Total | 43 | |||

| State | Election center | Clan | Sub-clan | Number of seats |

| South West | Baidoa | Rahanweyn | Mirifle | 36 |

| Baidoa | Rahanweyn | Digil Dabare | 3 | |

| Baidoa | Darod | Ogaadeen | 2 | |

| Baidoa | Ajuraan | Ajuraan | 1 | |

| Baidoa | Dir | Gaadsan | 1 | |

| Barawe | Rahanweyn | Digil | 15 | |

| Barawe | Dir | Biyomaal | 4 | |

| Barawe | Barawaani | Barawwani | 1 | |

| Barawe | Hawiye | Gan-darshe | 1 | |

| Barawe | Hawiye | Hintire | 1 | |

| Barawe | Hawiye | Reer Aw-xasan | 1 | |

| Barawe | Hawiye | Silcis | 1 | |

| Barawe | Hawiye | Wacdaan | 1 | |

| Barawe | Hawiye | Wadalan | 1 | |

| Total | 69 | |||

| State | Election center | Clan | Sub-clan | Number of seats |

| Galmudug | Dhusamareb | Hawiye | Muruunsade | 7 |

| Dhusamareb | Darod | Marrexaan | 4 | |

| Dhusamareb | Hawiye | Duduble | 4 | |

| Dhusamareb | Hawiye | Cayr | 3 | |

| Dhusamareb | Hawiye | Wacaysle | 3 | |

| Dhusamareb | Dir | Dir-surre | 2 | |

| Dhusamareb | Hawiye | Saleban | 2 | |

| Dhusamareb | Galgala/Sab | Tumaal | 1 | |

| Galkacyo | Hawiye | Sacad | 3 | |

| Galkacyo | Hawiye | Saruur | 3 | |

| Galkacyo | Hawiye | Shikhaal | 2 | |

| Galkacyo | Dir | Dir-qubeys | 1 | |

| Galkacyo | Hawiye | Madhibaan | 1 | |

| Galkacyo | Hawiye | Saleban | 1 | |

| Total | 37 | |||

| State | Election center | Clan | Sub-clan | Number of seats |

| Hirshabelle | Jowhar | Hawiye | Abgal | 6 |

| Jowhar | Hawiye | Yaxar | 2 | |

| Jowhar | Hawiye | Shiidle | 2 | |

| Jowhar | Hawiye | Ciise Mudulood | 1 | |

| Jowhar | Hawiye | Hilibi | 1 | |

| Jowhar | Hawiye | Moobleen | 1 | |

| Beledweyne | Hawiye | Xawaadle | 8 | |

| Beledweyne | Hawiye | Gugundhabe | 5 | |

| Beledweyne | Hawiye | Gaal-jecel | 4 | |

| Beledweyne | Hawiye | Ciise Mudulood | 2 | |

| Beledweyne | Carab Somali | Carab Somali | 1 | |

| Beledweyne | Hawiye | Reer-aw Xasan | 1 | |

| Beledweyne | Hawiye | Surre-fiqi Cumar | 1 | |

| Beledweyne | Bantu/Jareer | Makanne | 1 | |

| Beledweyne | Bantu/Jareer | Reer Shabelle | 1 | |

| Total | 38 | |||

| State | Election center | Clan | Sub-clan | Number of seats |

| Somaliland | Mogadishu | Isaaq | Isaaq | 28 |

| Mogadishu | Dir | Samaroon | 9 | |

| Mogadishu | Dir | Ciise | 8 | |

| Mogadishu | Dir | Muuse-dhari | 1 | |

| Total | 46 | |||

| State | Election center | Clan | Sub-clan | Number of seats |

| Banadir | Mogadishu | Banaadiri | Banaadiri | 5 |

| Total | 5 | |||

Distribution of seats in the Upper House (54 seats)

| State | Election center | Clan | Sub-clan | Number of seats |

| Puntland | Garowe | Darod | Dhulbahante | 2 |

| Garowe | Darod | Ali Saleban | 1 | |

| Garowe | Darod | Awrtable | 1 | |

| Garowe | Darod | Ciise Maxamuud | 1 | |

| Garowe | Darod | Cumar Maxamuud | 1 | |

| Garowe | Darod | Dishiishee | 1 | |

| Garowe | Darod | Jambeel | 1 | |

| Garowe | Darod | Leelkase | 1 | |

| Garowe | Darod | Osman Mohamud | 1 | |

| Garowe | Darod | Warsangeli | 1 | |

| Total | 11 | |||

| State | Election center | Clan | Sub-clan | Number of seats |

| Jubaland | Kismayo | Darod | Absame | 2 |

| Kismayo | Darod | Mareexan | 2 | |

| Kismayo | Darod | Gari Kombe | 1 | |

| Kismayo | Rahanweyn | Mirifle | 1 | |

| Kismayo | Dir | Biyomaal | 1 | |

| Kismayo | Hawiye | Cawrmale | 1 | |

| Total | 8 | |||

| State | Election center | Clan | Sub-clan | Number of seats |

| South West | Baidoa | Dir | Biyomaal | 1 |

| Baidoa | Rahanweyn | Boqol-hore Mirifle | 1 | |

| Baidoa | Rahanweyn | Elay Mirifle | 1 | |

| Baidoa | Rahanweyn | Gare Digil | 1 | |

| Baidoa | Rahanweyn | Geelidle | 1 | |

| Baidoa | Rahanweyn | Hadamo Mirifle | 1 | |

| Baidoa | Rahanweyn | Jiido Digil | 1 | |

| Baidoa | Rahanweyn | Leesan Mirifle | 1 | |

| Total | 8 | |||

| State | Election center | Clan | Sub-clan | Number of seats |

| Galmudug | Dhusamareb | Hawiye | Saleban | 2 |

| Dhusamareb | Darod | Marrexaan | 1 | |

| Dhusamareb | Dir | Dir | 1 | |

| Dhusamareb | Hawiye | Cayr | 1 | |

| Dhusamareb | Hawiye | Duduble | 1 | |

| Dhusamareb | Hawiye | Muruunsade | 1 | |

| Dhusamareb | Hawiye | Sacad | 1 | |

| Total | 8 | |||

| State | Election center | Clan | Sub-clan | Number of seats |

| Hirshabelle | Jowhar | Hawiye | Abgal Mudulood | 2 |

| Jowhar | Hawiye | Xawaadle | 2 | |

| Jowhar | Bantu/Jareer | Jareer-sadex Cumarow | 1 | |

| Jowhar | Hawiye | Jajeele | 1 | |

| Jowhar | Hawiye | Gaal-jecel | 1 | |

| Jowhar | Hawiye | Hilibi | 1 | |

| Jowhar | Hawiye | Ujeejeen Mudulood | 1 | |

| Total | 8 | |||

| State | Election center | Clan | Sub-clan | Number of seats |

| Somaliland | Mogadishu | Dir | Samaroon | 2 |

| Mogadishu | Isaaq | Habar Yoonis | 2 | |

| Mogadishu | Isaaq | Habar Jeclo | 2 | |

| Mogadishu | Dir | Ciise | 1 | |

| Mogadishu | Isaaq | Arab | 1 | |

| Mogadishu | Isaaq | Cidagale | 1 | |

| Mogadishu | Isaaq | Ciise Muuse | 1 | |

| Mogadishu | Isaaq | Sacad Muuse | 1 | |

| Total | 11 | |||