In recent years, Peru has been through multiple political crises, earning a reputation in Latin America for its unstable politics. Now the country is approaching the first round of a presidential election scheduled for 11 April 2021 and, with 18 candidates running for the position, the latest polls indicate an uncertain outcome. Five candidates are tied and a quarter of the electorate remains undecided on who to vote for (El País, 4 April 2021).

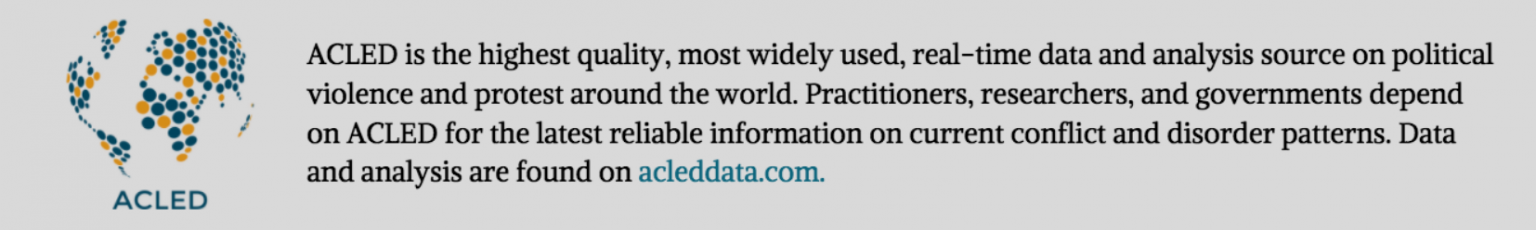

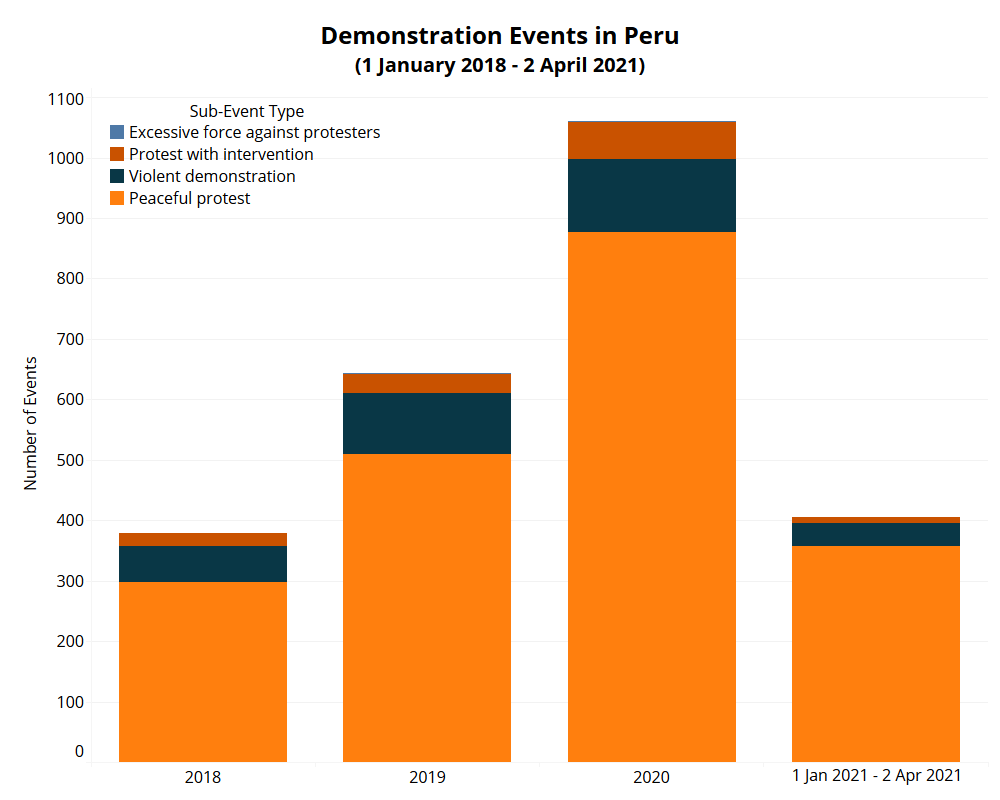

This report reviews demonstration trends in Peru from 2018 to 2021. ACLED data show that increased political instability led to a significant spike in the number of demonstration events in 2020 (see figure below). The population’s growing dissatisfaction with enduring government corruption and an economic crisis exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic have contributed to the rise in demonstrations. Demonstrations involving farmers have likewise increased during the pandemic period in response to legislation that they view as adversely affecting their business. The outcome of the presidential election will impact the trajectory of these trends in the coming years.

The 2018 Presidential and Judicial Crises

Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, commonly known as PPK, resigned from the presidency on 23 March 2018, after a video was leaked showing key allies buying votes to prevent his removal from office (La Republica, 21 March 2018). Kuczynski resigned as Congress was preparing to vote for the second time in three months on his removal from the presidency on the grounds that he was “morally incapable.” While immorality is not an impeachable offense, the term, which originally refers to a mental disability, is often used in Peru to oust its leaders (Americas Quarterly, 10 November 2020). The procedure of impeachment itself is reserved for specific and very limited cases.

First Vice President Martín Vizcarra was sworn-in on the same day as Kuczynski’s resignation. Vizcarra took power on the promise that he would fight systemic corruption on all government levels, which inspired Peruvians to trust him (El Periodico, 29 November 2019). At the end of 2016, the Peruvian Prosecutor’s Office started investigating the Brazilian construction company Odebretch, which had paid millions of dollars to obtain political favors and lucrative contracts in Peru. This corruption scandal involved several politicians, and included accusations of bribes and campaign financing. Four Peruvian presidents were placed under investigation in relation to this scandal: Kuczynski (2016-2018), Ollanta Humala (2011-2016), Alejandro Toledo (2001-2006), and Alan García (1985-1990, 2006-2011). Two-time president García killed himself with a shot to the head on 17 April 2019 when police officers arrived at his house to arrest him.

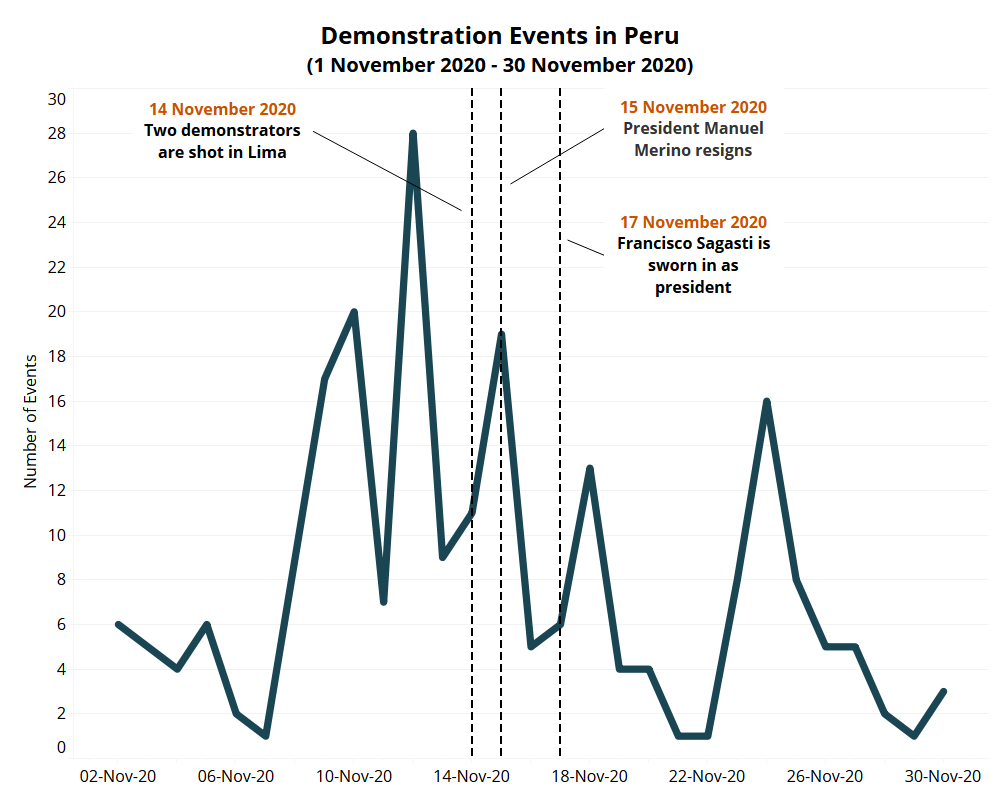

While corruption scandals plagued Peruvian politics, demonstrations around political issues were limited in 2018. Nevertheless, demonstrations were reported in Peru against corruption in July 2018 (see figure below). Thousands of people took to the streets in the capital city of Lima after audio tapes of conversations between judicial officials were leaked (El País, 19 July 2018). The audio tapes revealed that judges and magistrates discussed plans to trade favors, help convicted criminals, and secure jobs for friends (Reuters, 19 July 2018). On 18 July, the judicial branch declared a 90-day state of emergency on the grounds that they would carry out reforms to tackle the scandal (InSight Crime, 9 August 2018). The reforms were not specified then, but in the subsequent months, the president pushed for several draft bills which aimed to curb corruption. On 19 July, the head of the Supreme Court resigned due to the institutional crisis, although he was not directly involved in the scandal (Associated Press, 19 July 2018).

The 2019 Constitutional Crisis

After more than a year as president, on 30 September 2019, Vizcarra dissolved Congress and called for parliamentary elections. This decision came after Congress elected a new member of the Constitutional Court, contrary to Vizcarra’s wishes. The move to appoint a new member of the Constitutional Court was seen by the president as an attempt to block his anti-corruption campaign, which included several draft bills proposed to the Congress (Deutsche Welle, 30 September 2019). At that time, Vizcarra was not affiliated with a political party, and Congress was fragmented into several different electoral groups (Americas Quarterly, 17 September 2020). The fragmentation made it difficult to approve laws and make significant decisions in Congress. The opposition against Vizcarra was led by members of the Popular Force Party (FP), party of former President Alberto Fujimori (1990-2000), who was involved in major corruption and human rights abuse scandals.

The decision to dissolve Congress was well received by Peruvians, with 89.5% in favor of Vizcarra’s position (Andina, 5 October 2019). Citizens demonstrated outside the Congress to show their support for the measure. On 26 January 2020, parliamentary elections were carried out. The new elections did not result in significant change to the composition of Congress, as no party received more than 11% of the seats for representatives (BBC, 27 January 2020). Congress continued to avoid bills that aimed to curb corruption, further hindering the government’s attempts to fight endemic corruption in the country.

Between 26 September and 3 October, during the peak days of the constitutional crisis, eight protests were reported in Peru in favor of Vizcarra’s decision to dissolve Congress, while no protests in defense of the Congress were reported (see figure below). The 2019 constitutional crisis highlighted the population’s support for anti-corruption measures.

The 2020 Presidential Crisis

The coronavirus pandemic brought new challenges to Peru. Before the pandemic, approximately 73% of the Peruvian workforce was composed of informal employees, with no formal registration, stability, or labor benefits (RPP, 17 November 2020). This percentage might have reached as much as 90% due to the economic crisis caused by the pandemic (Gestion, 27 August 2020).

The conditions for those in the informal labor market worsened during the pandemic (Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 31 August 2020). The increasing precariousness of the labor market led different labor groups to call for demonstrations. People from the health, farming, construction, education, and transport sectors protested throughout the year. They mostly demanded better contract conditions, formal long-term contracts, and payment of delayed salaries. In June 2020, the Workers’ General Confederation of Peru (CGTP) called for a nationwide protest to demand the government restart civil construction works, which have been suspended due to the pandemic. Similarly, on 26 August, public health workers led a nationwide protest to call for additional medical supplies and the payment of a bonus for workers treating coronavirus patients.

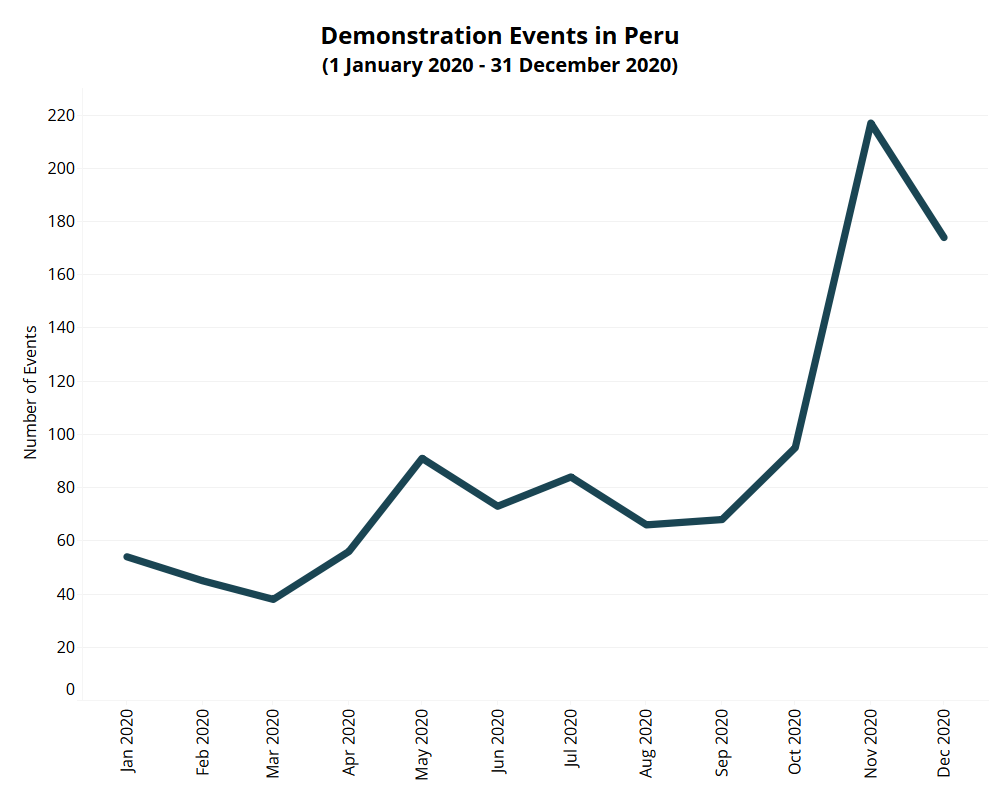

While Peruvians were increasingly taking to the streets in the midst of the pandemic, in November, the country once again entered a troubling political crisis when the Congress called for the removal of the president. Vizcarra was placed under investigation due to corruption charges during his time as governor of the Moquegua region from 2011 to 2014 (El Comercio, 10 November 2020). On 10 November, Vizcarra was ousted on allegations of “moral incapacity,” the same allegations used against Kuczynski.

However, the swearing-in of Manuel Merino of the Popular Action Party as the President of Congress was met with significant public opposition. Citizens took to the streets, claiming the president’s removal was a maneuver by the opposition, who disliked Vizcarra’s anti-graft reforms (The Guardian, 10 November 2020). Many Peruvians also perceived Vizcarra’s controversial removal as a coup d’état (La Republica, 10 November 2020). Several demonstrations were reported across the country, with thousands of Peruvians marching through the streets (Reuters, 14 November 2020) (see figure below). Citizens rejected the lack of transparency in the removal procedure and called for the appointment of a new president (La Republica, 15 November 2020).

After only six days as president, Merino resigned. His decision came after two young men were shot dead by police officers during violent demonstrations in Lima. Following a vote in Congress, centrist legislator Francisco Sagasti (Purple Party) was chosen by Congress representatives to replace Merino. He was sworn-in as the president of Peru on 17 November (La Republica, 16 November 2020).

More than 100 demonstration events were reported between 9 and 17 November, during the peak days of the presidential crisis, accounting for approximately 10% of all demonstration events reported in 2020 in Peru (see figure below). Most of these events were demonstrations in opposition to Merino being sworn-in as president. However, even after Merino’s resignation, citizens continued to protest across the country, seeking justice for the victims who died or were injured during the demonstrations. They also called for a new Constituent Assembly in an attempt to curb corruption in the country (La Republica, 16 November 2020).

Increased Demonstrations By Farmers in December 2020

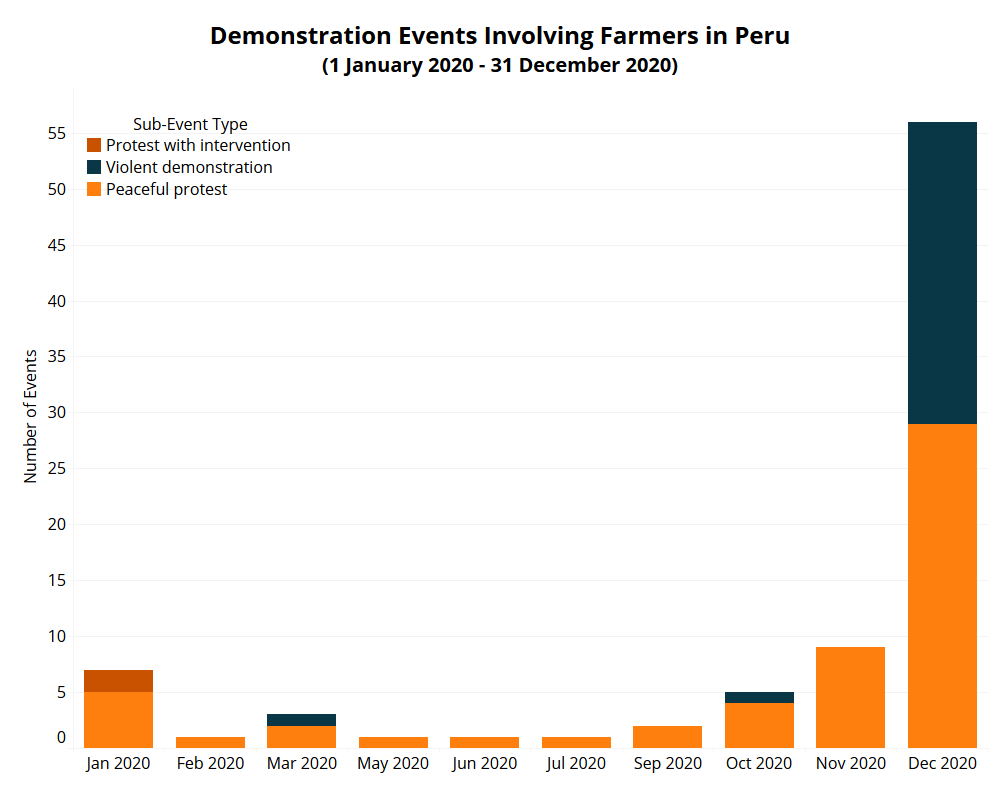

After the presidential crisis of 2020, demonstrations demanding the improvement of working conditions continued across the country. During the month of December, farmers blocked several highways to demand higher wages and full labor rights, marking a significant increase in the number of demonstration events involving farmers (see figure below). They also demanded the annulment of the Agrarian Promotion Law, a regulation that should have expired at the end of 2020, but was extended until 2031. Farmers claimed the legislation was unjust, as it exempted them from benefits such as annual bonuses and vacation time, and they called for the approval of a new law that would modify the current one. Violent clashes were reported between demonstrators and state forces, and at least three farmers were killed by police officers.

On 31 December, Congress approved the new law and demonstrations came to a halt (El Comercio, 31 December 2020). Although no new demonstrations over this issue were reported so far in 2021, agricultural producers have expressed concerns that the new law will force small and medium-sized companies to enter the informal economy or close their business (El Comercio, 31 December 2020). The law establishes an increase in salaries for farmers and the implementation of bonuses, which will increase costs of farmer production with no government subsidies available (El Comercio, 17 December 2020). The economic crisis caused by the pandemic, coupled with the difficulties in implementing the new law, could lead farmers to demonstrate again in the future.

The 2021 Presidential Election

On 3 April 2021, Peru registered its highest single-day total of coronavirus-related deaths at 294 deaths (AlJazeera, 4 April 2021). The recent surge in infections, coupled with stricter lockdown measures, have led to increased demonstrations by workers in various sectors (see figure below).

In the beginning of February this year, dozens of merchants in Lima district took to the streets for five days to demonstrate against the total lockdown introduced in 10 regions of the country following the increase in coronavirus infections (Diario Correo, 31 January 2021). Protesters criticized the measures imposed by the president on the grounds that the lockdown constrains their individual liberties. They also opposed the coronavirus vaccination program, claiming the vaccines were unsafe (El Comercio, 1 February 2021). Protests were also reported in the cities of Arequipa and Tacna at the end of the month, when hundreds of businessmen protested against the total lockdown (Diario Correo, 13 February 2021; Diario Correo, 15 February 2021).

As well, throughout the week of 15 March, hundreds of transport workers went on strike and staged demonstrations, blocking highways across the country (Diario de Chimbote, 17 March 2021). Demonstrations increased by over fivefold that week, with over 150 events reported. The nationwide demonstrations were called by the National Union of Transport Workers of Peru (UNT) to demand gasoline and toll prices be reduced. They claim the increased price of fuel, coupled with the economic crisis, has worsened their living conditions. On 20 March, the UNT reached an agreement with the government and demonstrations were suspended (Andina, 20 March 2021).

Conclusion

As Peruvians prepare to go to the polls, conflict between the presidency and the legislature threatens reforms and effective measures against corruption in the country. Endemic corruption will likely undermine Peru’s economic recovery after the coronavirus pandemic despite the economy’s previously strong performance. Additionally, the new agrarian law and concerns over its effective implementation could trigger more demonstrations by farmers already impacted by the pandemic. The outcome of the presidential election will affect the trajectory of political disorder in the country for years to come.