The ACLED-Religion pilot project collects real-time data on religious repression and disorder in the Middle East and North Africa. This spotlight report analyzes key trends from the latest data on Bahrain, Iran, Iraq, and Yemen. For more, download the full ACLED-Religion dataset or explore the data through the interactive ACLED-Religion dashboard.

Bahrain: Ongoing Repression of Shiite Religious Practices

Bahrain is an island kingdom ruled by the Sunni Muslim Al Khalifa royal family. The Al Khalifa regime is accused of systematically discriminating against the country’s Shiite community, which is estimated to account for 60% to 70% of Bahrain’s Muslim population (BICI, 10 December 2011). Discriminatory practices affect Shiite believers across a wide array of domains, including employment, freedom of expression, and political rights (USCIRF, April 2020). The Shiite community faces exclusion from the military and security apparatuses (CSIS, 9 December 2016), the arbitrary revocation of Bahraini citizenship (OHCHR, 18 April 2019), and the denial of medical care for prisoners (Amnesty International, 28 September 2018).

The sectarian divide in Bahrain is stoked by political tensions. The monarchy sees the Shiite popular majority as a threat, and has historically used alleged ties between Shiite opposition groups and the Iranian regime to justify the systematic denial of political rights. As demonstrated by the “Bandargate” scandal (the public revelation of a report on the regime’s plan to marginalize the Shiite community), the Al Khalifa have also pursued a policy of ‘Sunnization’ of the Bahraini population (Le Monde Diplomatique, 19 October 2006). However, the repression of the Shiite community is not only driven by political considerations: Shiite identity is also targeted for purely sectarian reasons.

While the celebration of Shiite religious festivals — including Ashura, the commemoration of the martyrdom of Imam Al Husayn and his family — is technically permitted in Bahrain, police forces have consistently harassed worshippers and engaged in violent forms of crowd control during these events. According to a recent report, in 2019, Bahrain’s security forces refrained from using tear gas against Ashura worshippers, signalling a positive development, though the government still “summoned at least 20 religious leaders regarding the content of their sermons and prayers, and it restricted Ashura ritual processions” (USCIRF, April 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has recently contributed to renewed limitations on religious freedom. On 26 August 2020, a few days before Ashura, the Jaffaria Endowment Directorate imposed restrictions specifically aimed at targeting Shiite worshipers and their congregation halls, the matams (Ministry of Health, 26 August 2020). Subsequently, under the pretext of enforcing COVID-19 restrictions, Bahraini authorities have summoned and detained multiple Shiite civilians and religious leaders, limiting their religious freedom and cracking down on matams during the Islamic month of Muharram.1Unpublished information provided by Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain (ADHRB).

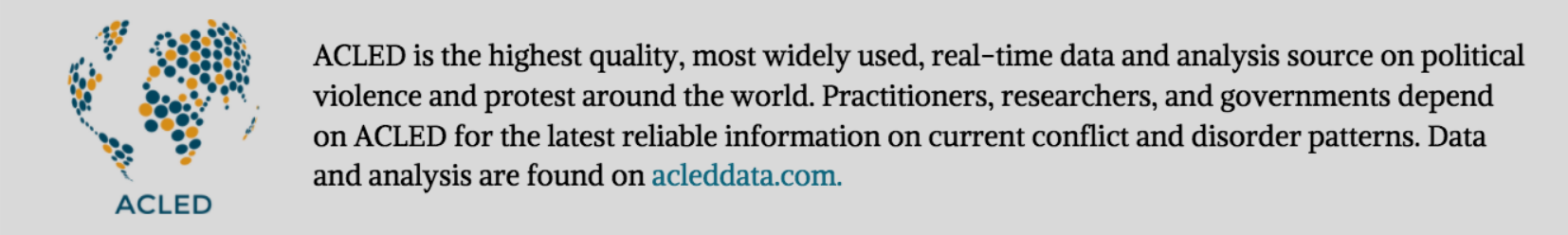

ACLED-Religion data shed light on the long-term consequences of these restrictions and the repression of Shiite religious practices. Between January and March 2021, ACLED-Religion records six judicial harassment events targeting various Shiite practices (see figure below), including Ashura-related celebrations, the call to prayer (adhan), and other unspecified rituals. On 10 March 2021, police forces summoned a Shiite citizen for participating in commemorations of Imam Musa Aal- Kadhim, the seventh Twelver Imam (LuaLua Tv, 11 March 2021). A second major trend is the repression of Shiite religious practices and beliefs in prison. ACLED-Religion records three discrimination events involving restrictions on the religious practice of Shiite inmates. The particular targeting of Shiite clerics in prison reflects the systematic “sectarian discrimination” that Shiite prisoners experience in Bahrain (Amnesty International, 28 September 2018), a trend exemplified by the attack on Sheikh Zuhair Ashour in Jaw Prison on 14 March and by the medical mistreatment of Sayed Kamel Hashemi on 30 March (Manama Post, 30 March 2021; 14th February Coalition, 18 March 2021). While some recent reports suggest that religious freedom conditions have improved in Bahrain (USCIRF, April 2021), others find that little progress has been made to end discrimination and judicial harassment targeting the Shia community (Freedom House, 2021; Amnesty International, 2021). ACLED-Religion data show that the repression of Shiite religious practice remains systematic and ongoing.

Iran: Targeting of Religious Minorities

The Islamic Republic of Iran is a ‘clerical oligarchy’ (FIDH, August 2003; ISPI, 2011) founded on the principle of the Velayat-e Faqih, the ‘Government of the Islamic Jurist.’ The Iranian constitution stipulates that Islam is the official religion and “the madhhab (school of law) is the Twelver Jafari school” (Islamic Parliament of Iran). Over 90% of the Iranian population adheres to Twelver Shiism. In spite of recent initiatives by President Hassan Rouhani, the Iranian regime is still responsible for engaging in “systematic and ongoing” violations of religious freedom (USCIRF, April 2020).

Article 12 of the Iranian constitution accords “full respect” and “official status” to Muslim minorities. Yet, despite these legal provisions, Sunni Muslims are reported to be among the most persecuted minorities in the country (HRANA, 2019). Also the Gonabadi dervishes — a Sufi sect that identifies with Shiite Islam — have faced increasing levels of repression since former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad took power in 2005 (Al Jazeera, 27 February 2018). The election of President Rouhani in 2017 has not substantially changed this trend, and regime hardliners have been found guilty of persecuting Sufis in the recent past (USCIRF, August 2020). In 2018, police forces cracked down on Sufi protests, arresting 300 individuals (Refworld, 20 February 2018).

Article 13 specifies that Christian, Zoroastrian, and Jewish minorities are recognized by the state and granted the right to practice their religion. However, conversion to one of these denominations is tantamount to apostasy and members of these groups are politically sidelined and discriminated against when seeking employment (FIDH, August 2003). Article 14 regulates the status of unrecognized minorities, including the Baha’is, who are viewed by the regime as “unprotected infidels” (FIDH, August 2003). The Baha’is are the largest non-Muslim minority group in the country, consisting of more than 350,000 individuals (United Nations, 18 July 2019). They are considered a heretical “deviant sect” of Islam, and, for this reason, they suffer discrimination both economically and educationally. They are often the object of media hate speech campaigns (Weiner, October 2019).

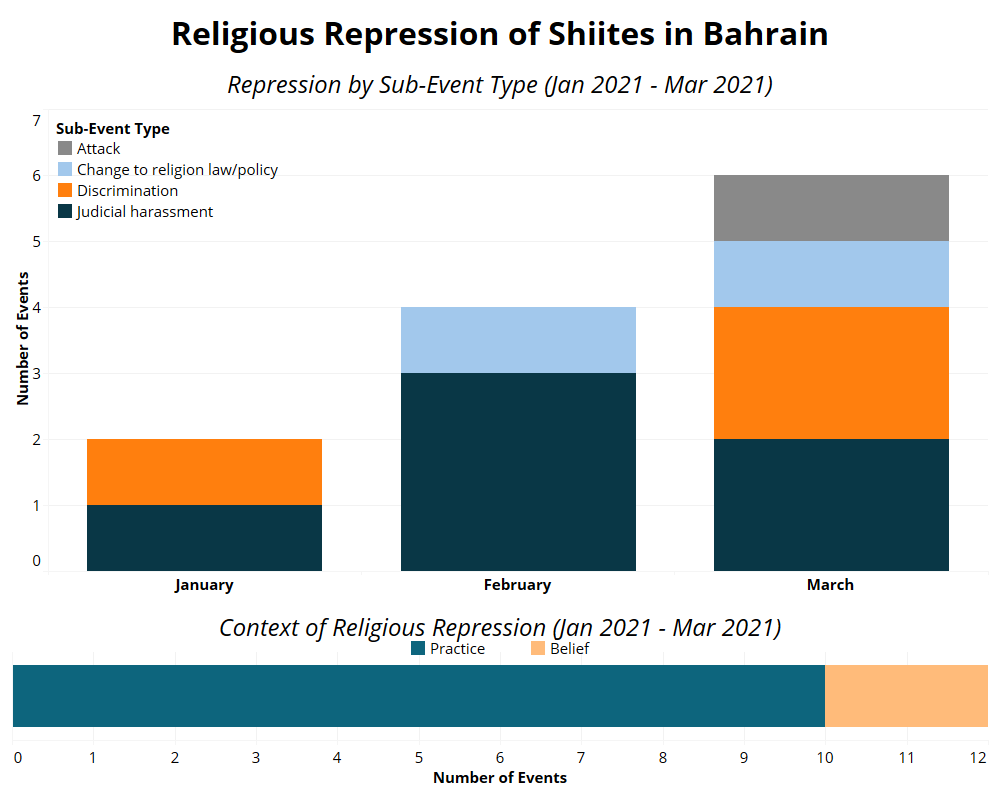

Between January and March 2021, ACLED-Religion records 71 repression events perpetrated by state forces against religious groups. The Sunni denomination, although legally recognized, is the victim of 37% of the repression events (see figure below). As also recorded in other countries (e.g. Egypt and Iraq), Sunni believers are often ascribed a ‘stigmatized affiliation’2If a perpetrator assigns a religious affiliation to a victim to justify an act of repression or discrimination – and the victim’s self-ascriptive religious affiliation remains unknown – the imposed religious affiliation is coded generically as “Stigmatized Affiliation.” Check the ACLED-Religion methodology brief for more information. and convicted on charges of alleged connections with “Salafi groups.”

The targeting of religious minorities is frequently camouflaged with political pretexts. The repression of Sufi believers still continues in connection with the 2018 protests in the form of two judicial harassment and discrimination events (see figure below). On 16 February 2021, a Dervish died due to lack of medical treatment and torture in prison. Also, Shiite believers are targeted by state repression for expressing an unorthodox version of the Twelver faith. Among non-Muslim minorities, Baha’is are the most targeted group, and were subjected to 23 repression events during this period (see figure below). In most cases, their repression is justified with spurious accusations of “conspiracy against national security.” Similarly, Christian converts are accused of “propaganda against the state.” These trends seem to confirm that, despite President Rouhani’s pledges to address challenges to religious freedom, the Iranian regime is still systematically targeting religious minorities.

Iraq: ‘Immoral’ Leisure Activities and the Emergence of ‘Façade’ Shiite Militias

In Iraq, ‘immoral’ leisure activities have been the subject of an ideological dispute between state forces, religious minorities, and Islamist movements. At the onset of Saddam Hussein’s rule in the 1970s, alcohol was widely available (IWPR, 18 January 2008). In response to growing Islamist movements, Hussein enforced the public observation of Islam after 1991, closing down night clubs, casinos, and bars (USIP, August 2003). He also banned Muslim citizens from selling alcohol, thus leaving the trade to Christians and Yazidis (Independent, 23 October 2011).

After Hussein’s fall in 2003, a surge in Islamic identity politics reshaped the country’s religious landscape. Shiite militias engaged in frequent acts of vigilantism, with the Mahdi Army specifically targeting liquor stores (New York Times, 16 July 2004). By 2006, liquor stores had closed their doors, as sectarian violence erupted between Sunni and Shiite forces in and around Baghdad. Beginning in 2008, a gradual improvement in the security situation allowed for a return of alcohol sales (IWPR, 18 January 2008).

The current debate around alcohol sales in Iraq has been framed in ‘moral’ and ‘religious’ terms. In October 2016, the Iraqi parliament voted to ban the sale, import, and production of alcohol, on the grounds that alcohol trade would be contrary to Islam and to the constitution (BBC, 23 October 2016; WSJ, 23 October 2016; DW, 24 October 2016). The emergence of Shiite militias affiliated with the anti-Western muqawama (resistance) has inaugurated a new chapter in this trend (Washington Institute, 19 January 2021).

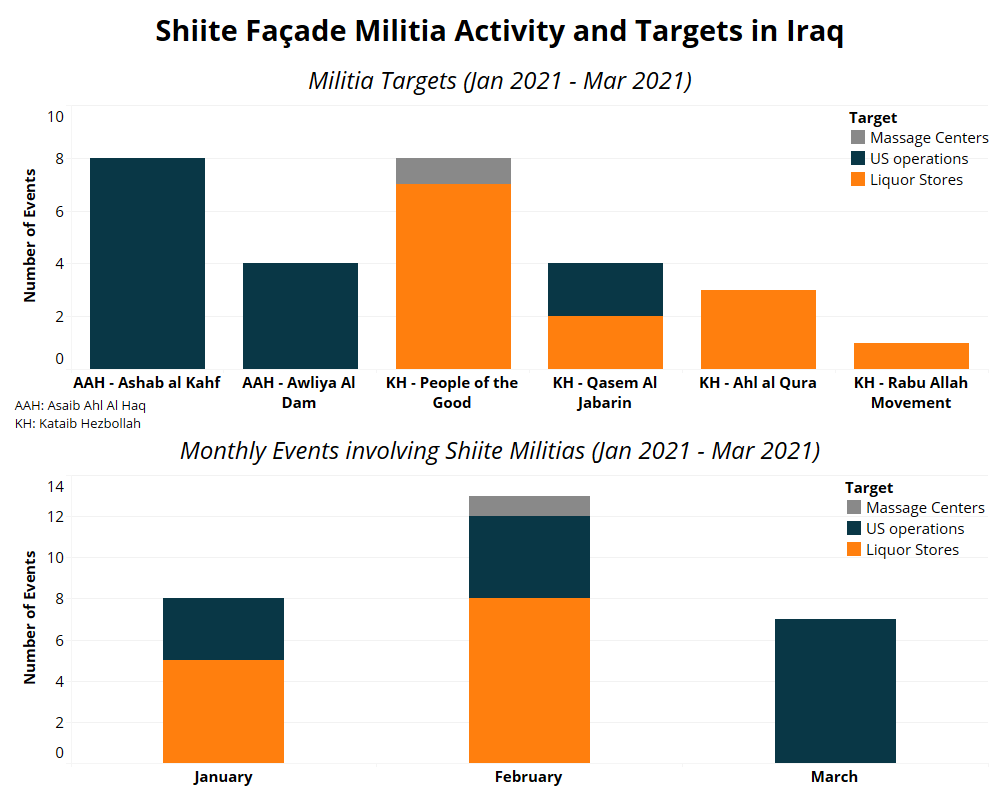

Rabu Allah and People of the Good are new groups operating as ‘façade’ militias — mere “brands for certain types of activities” (Washington Institute, 19 January 2021) — on behalf of the Iranian-backed Kataib Hezbollah (KH) militia. Since late 2020, KH militia have taken up the patrolling of Islamic morality. The groups have targeted liquor stores and massage centers, justifying their activities in religious terms (Al Monitor, 15 December 2020). Another Iranian-backed militia, Asaib Ahl Al Haq (AAH), has instead opposed these campaigns due to economic interests connected with tax extraction from related activities (Washington Institute, 19 January 2021). AAH façade militias — Ashab al Kahf and Awliya Al Dam — have also focused on domestic operations against the United States (US). This difference in focus has caused a fracture within the muqawama.

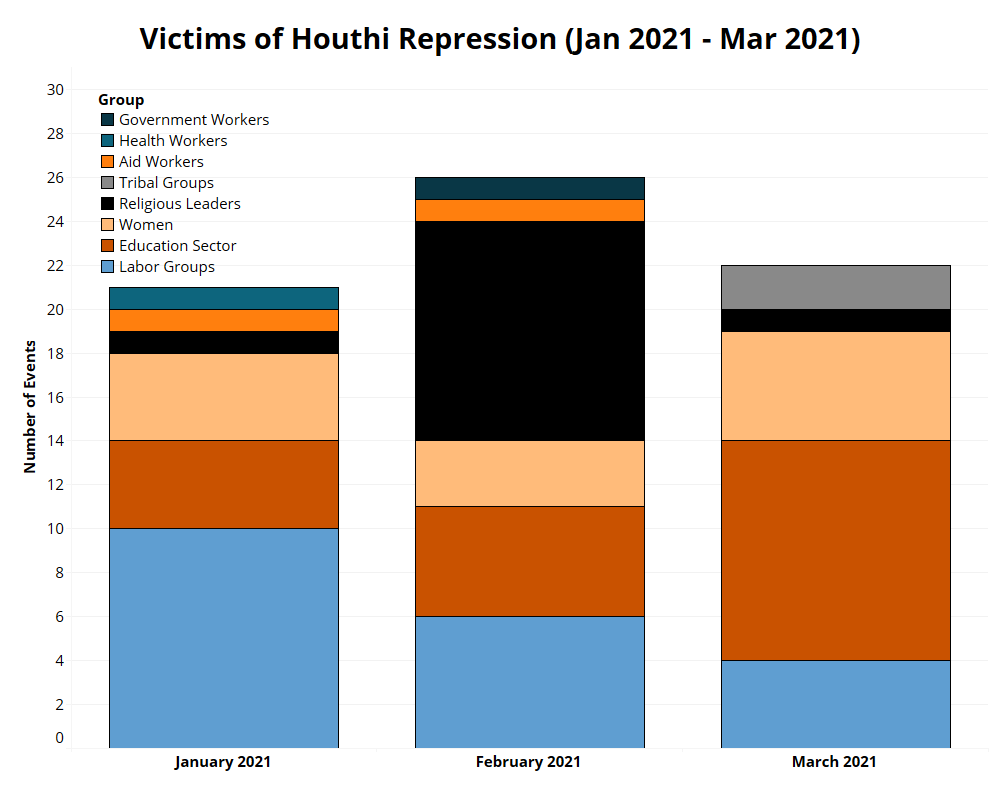

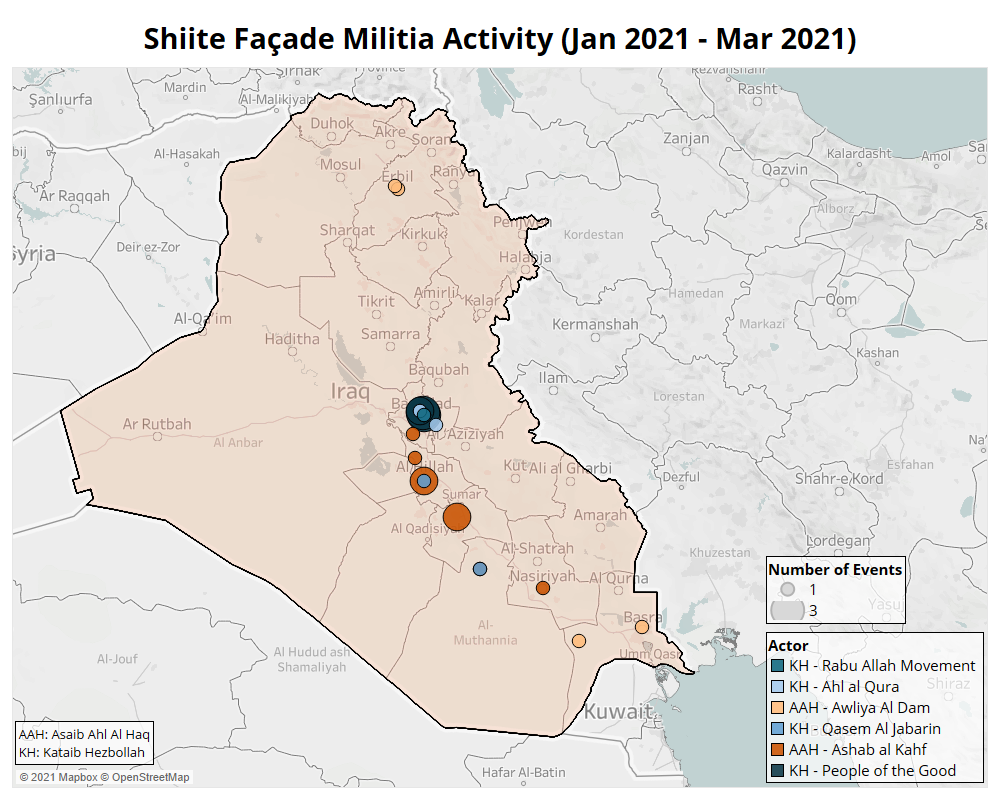

Between January and March 2021, ACLED-Religion has tracked the activity of the emerging Shiite façade militias in relation to ‘leisure’ activities and counter-US operations. The divergence in strategy between KH-affiliated and AAH-affiliated militias is evident, with the former almost exclusively targeting liquor stores and massage centers (see figure and map below). The only exception has been the KH-affiliated Qasem Al Jabarin militia, which has also been involved in convoy attacks. Interestingly, the identity of the victims (e.g. liquor store owners) and their religious affiliation is never reported. It is possibly taken for granted by sources and it would be reasonable to assume that the victims are Christians or Yazidis (Qantara, 16 December 2020). Notably, Rabu Allah activity appears limited, likely due to under-reporting because events are not claimed on a case-to-case basis by the group. This is reflected in the high number of attacks perpetrated by ‘unidentified’ militias (see figure below).

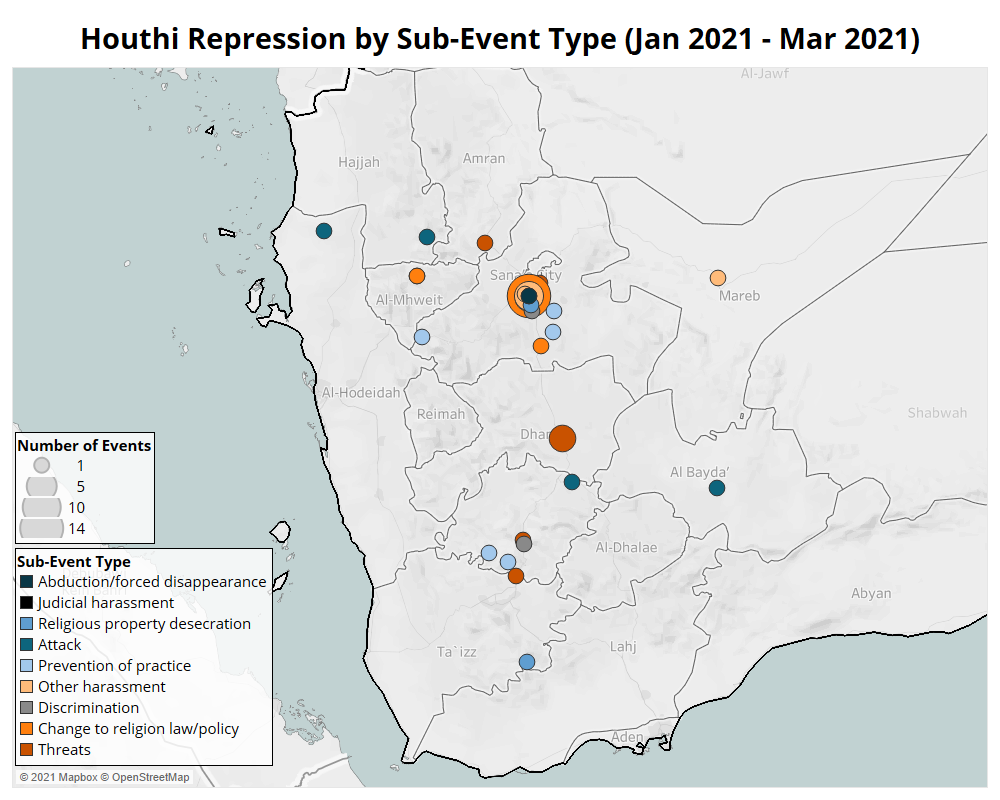

Yemen: Promoting Houthi Sectarian Ideology Amid the Battle for Marib

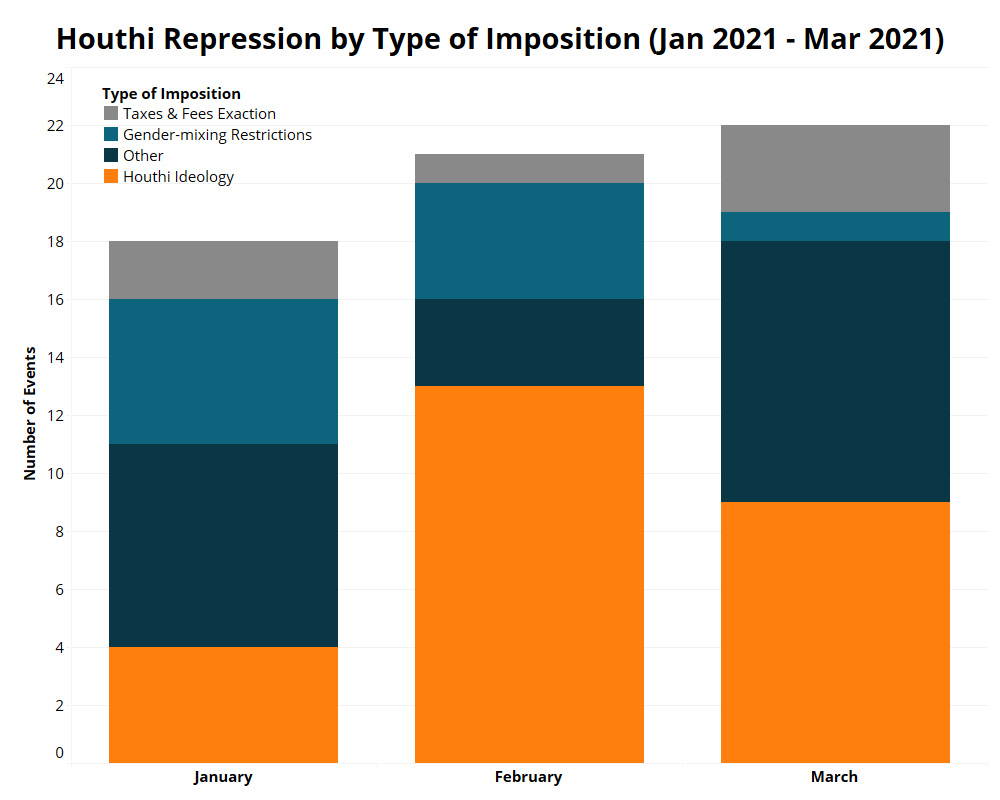

Six years after the eruption of Yemen’s civil war, the Houthi movement, or Ansar Allah, maintains undisputed control over state institutions in northern Yemen (ACAPS, 17 June 2020). Yet tensions are surfacing within the pro-Houthi ranks and their attempts at curbing internal dissent have ignited a “cycle of revolts and repression” (for more on infighting and repression in Houthi-controlled territories, see this ACLED report). Violence targeting civilians is but one of the repressive strategies deployed by the Houthis. In recent years, they have launched systematic campaigns aimed at strengthening the population’s ideological commitment. In addition, they have exacted new taxes and exploited the black market to gather resources for the frontlines (Shiban, 4 December 2020).

The imposition of a strict Islamic moral code lies at the core of Houthi repressive practices. Abdulmalik Al Houthi, the leader of Ansar Allah, portrays Fatima Al Zahra (Prophet Muhammad’s daughter) as the virtuous model for Muslim women, as opposed to Western ideals of femininity (al-Houthi, 8 March 2018). This is reflected in the enforcement of norms targeting women’s freedoms, including clothing practices, reproductive rights, and access to public spaces (Marib Press, 28 January 2021). Pro-Houthi state authorities have systematically enforced gender-mixing restrictions on universities and INGOs, justifying the imposition as in line with “the teachings of the Islamic religion” and the “Sharia” (Aden Al Ghad, 11 December 2020; Al Masdar, 7 January 2020).

Funding for this report was provided by the US Department of State’s Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations through the Quantifying Religious Repression and Religious Conflict grant. The views expressed in this report are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the United States Government.