The ACLED-Religion pilot project collects real-time data on religious repression and disorder in the Middle East and North Africa. This spotlight report analyzes key trends from the latest data on Egypt, Israel, and Palestine. For more, download the full ACLED-Religion dataset or explore the data through the interactive ACLED-Religion dashboard.

Egypt: Control of Public Morality and Sexual Behavior

The control of public morality plays a pivotal role in the way political and religious elites construct a state’s Islamic identity (Ayubi, 1991). In Egypt, moral and sexual constructs are closely intertwined (Ismail, 1999). The norms and practices aimed at curtailing sex work have been refashioned across time. Between the 1930s and the 1940s, Muslim activists campaigned for the abolition of licensed prostitution as a means to curb the spread of the “corrupting” Western influence. Sex work was abolished in 1951 to appease the religiously conservative Egyptian bourgeoise, and prostitution was framed in terms of “debauchery” and “vice” (Biancani, 2012).

In the 1990s, a widening range of Islamist movements endeavored to impose Islamic orthodoxy as the grid to shape the cultural arena. Exemplary of this trend was the campaign to censor allegedly ‘erotic’ billboard advertisements. In an attempt to co-opt and neutralize Islamist opposition, the Egyptian government started a gradual Islamization of state institutions (Ismail, 1999). In the wake of the internet era, the Mubarak regime positioned itself as “the guardian of public moralities” by turning cyberspace into a “crime scene” to monitor and police people’s sexual orientation and gender expression (Bahgat, 2004).

In contemporary Egypt, the regime of Abdel Fattah Al Sisi has systematically cracked down on the Muslim Brotherhood, while concurrently attempting to capture the consensus of its Muslim constituency. Once more, this endeavor has taken the form of a battle over public morality. The regime has reasserted the centrality of the family “founded on religion, morality, and patriotism,” and prohibited sexual intercourse outside of wedlock (Ahmed, 29 April 2020; State Information Service, 2014). A new anti-cybercrime law (no. 165/2018) has allowed state security to target social media influencers, and promoted new “repressive tactics to control cyber-space by policing women’s bodies” (Amnesty 13 Augsut 2020; Library of Congress, 5 October 2018). In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the regime has reacted to the proliferation of new social media by arresting prominent Tik Tok influencers under charges of “debauchery,” “lewdness,” and “vice” (Ahmed, 29 April 2020).

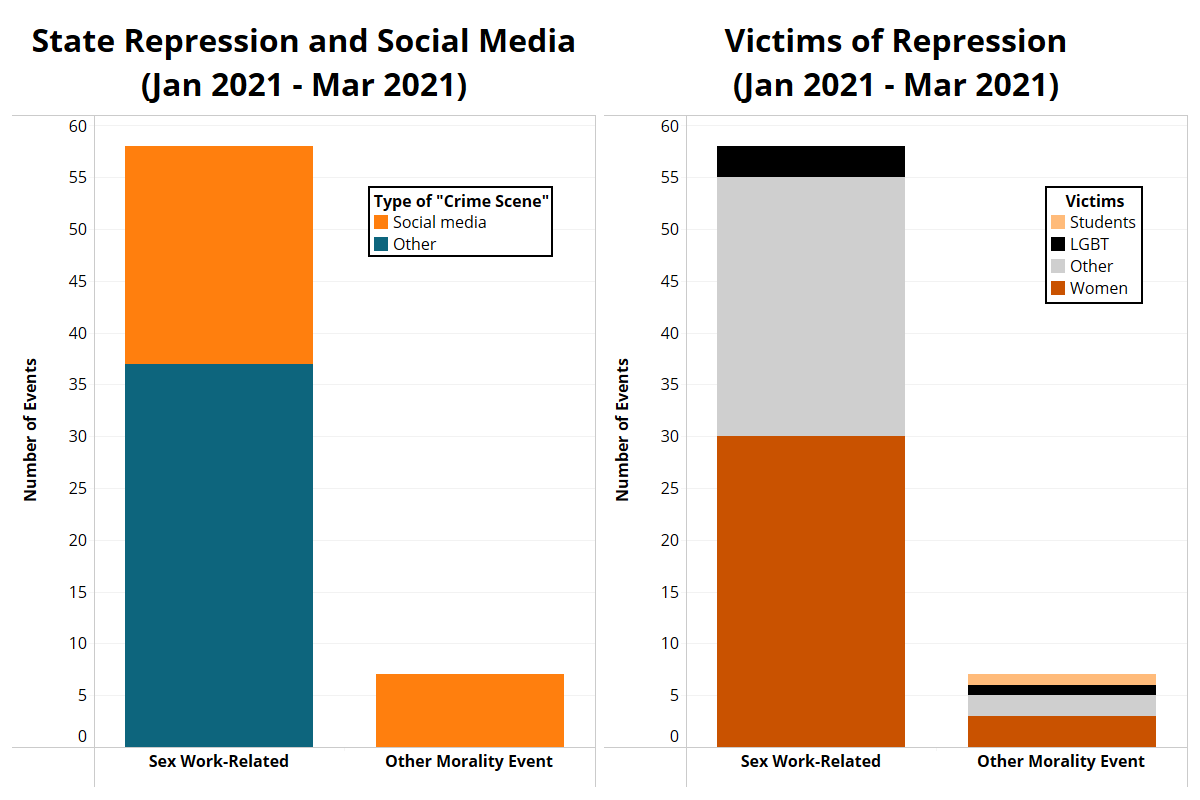

Between January and March 2021, ACLED-Religion records 65 judicial harassment events connected with the Egyptian regime’s efforts to control public morality. Over 89% of these events are related to sex work (see figure below). In all such cases, the alleged practice of prostitution is described with vague language referring to “immoral acts” and “debauchery.” The “crime scene” dimension of cyberspace is vividly reflected by the data. Sex work events are correlated with social media exposure in over 35% of the cases. In addition, all ‘non-sex work’ harassment events are triggered by the diffusion of allegedly immoral content on Tik Tok, YouTube, or Facebook (see figure below). The regime’s vision of public morality also translates on the societal level, with three mob violence events targeting civilians to repress their public sexual behavior. Overall, these trends confirm the increasing propensity of the Egyptian regime to repress non-normative sexual practices and orientations. In addition, the data highlight the repressive potential of online monitoring techniques (Abd El-Hameed, July 2018).

Israel and Palestine: Haredi Repression and COVID-19 Restrictions

Ultra-Orthodox or Haredi Jewish communities make up around 10% of Israel’s population (Haaretz, 21 April 2011). The Haredim adhere to various cultural and spiritual traditions that share some core features: strict adherence to the halacha (i.e. Jewish Law); devotion to Talmud and Torah study; emphasis on communal life; ‘isolation’ from non-Haredi communities; and strict obedience to the rabbi, the religious mentor (Friedman, 1991).

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, Haredi communities across the globe have refused to comply with related public health restrictions and social distancing measures (New York Times, 17 February 2021). In Israel, COVID-19 protocols have pitted ultra-Orthodox communities against state authorities for two main reasons. First, the restrictions have impinged on the Haredim’s everyday religious practices (e.g. the group study of Torah and the celebration of life-cycle events), thus threatening a fundamental dimension of their religious identity and the leadership of the rabbis (IDI, 13 April 2020). Second, the enforcement of COVID-19 restrictions has strengthened the Haredim’s perception of secular state authorities as “oppressors” (IDI, 13 April 2020).

Haredi violations of coronavirus protocols started in March 2020, when tens of thousands of ultra-Orthodox students — encouraged by Rabbi Chaim Kanievsky, a well-known Haredi scholar — attended their lessons on the first Sunday of restrictions (Haaretz, 15 March 2020). They continued to attend their lessons in the ensuing months. By the end of January 2021, a procession for the death of a rabbi was attended by thousands of Haredim during Israel’s third lockdown (BBC, 31 January 2021). On 7 February 2021, Israel started easing COVID-19 restrictions, and ultimately lifted limitations on religion-related practices on 15 February (France 24, 7 February 2021).

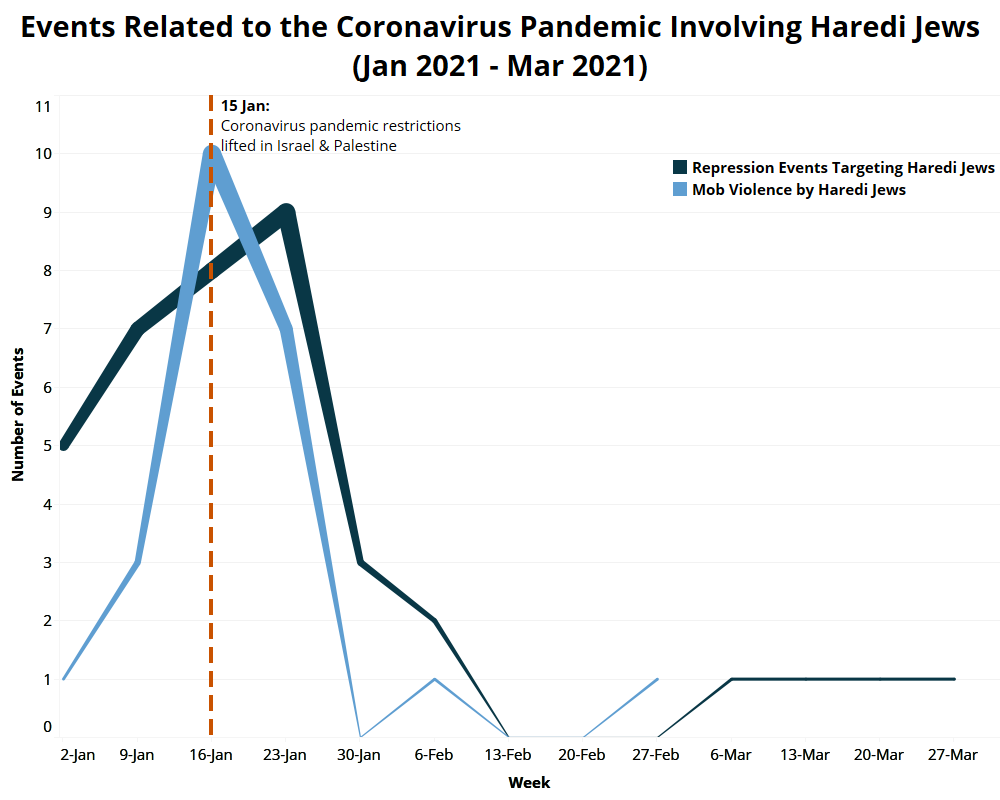

Between January and March 2021, ACLED-Religion records 51 repression events related to COVID-19 and involving ultra-Orthodox Jews. The lifting of restrictions on 15 February marks a shift in the perpetrators of violence against Haredim (see figure below). Before this date, the Haredim were mostly targeted by state forces for performing their religious practices in violation of COVID-19 restrictions. Haredi educational institutes and life-cycle celebrations were the main focus of state repression. ACLED-Religion data show a correlation between prevention of practice events targeting the Haredim and the subsequent eruption of mob violence between the Haredim and police forces in at least 15 events.

In turn, after 15 February, ACLED-Religion data show a decrease in the number of pandemic-related repression events, a change in the religious context, and a shift towards societal violence. On 21 February, a Haredi Jew was assaulted in Tel Aviv and explicitly accused of having caused the COVID-19 outbreak (Kikar, 21 March 2021). This event shows the increasing societal repression of the Haredim, incited and fuelled by relevant political leaders like Yair Lapid, head of the Yesh Atid party. Lapid called for the use of water cannons to disperse Haredi gatherings held in violation of coronavirus restrictions (Times of Israel, 6 February 2021). Overall, these trends clearly illustrate a gradual yet systematic transition of religious repression into religious disorder.

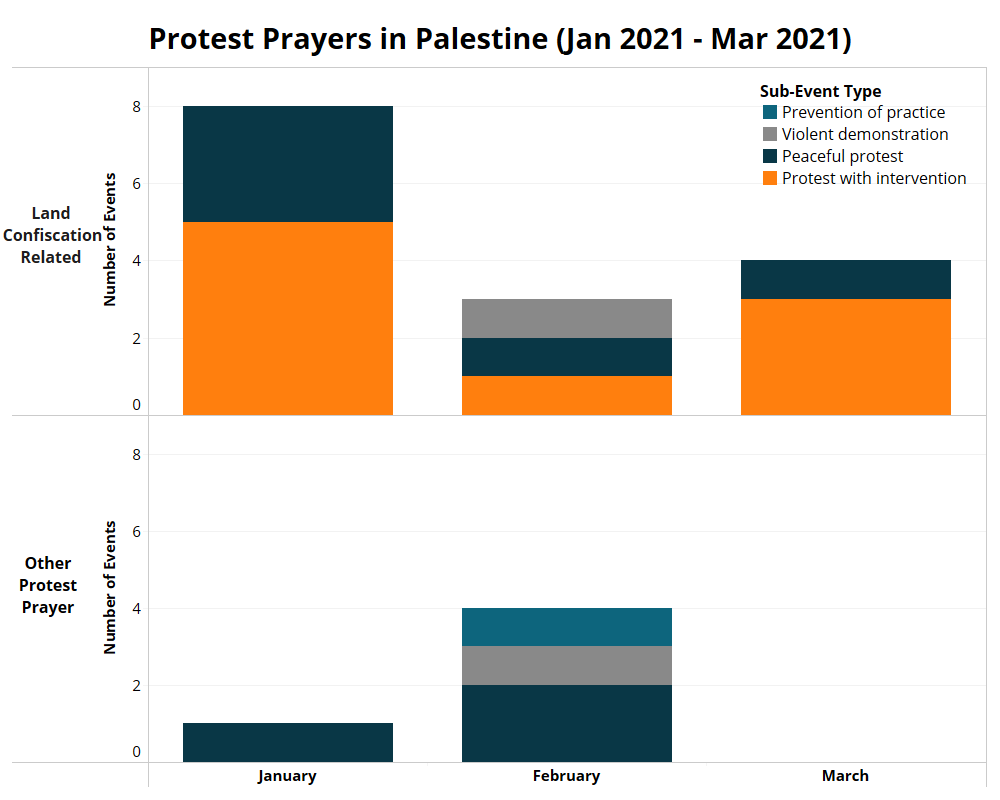

Palestine: Muslim Prayers of Contestation

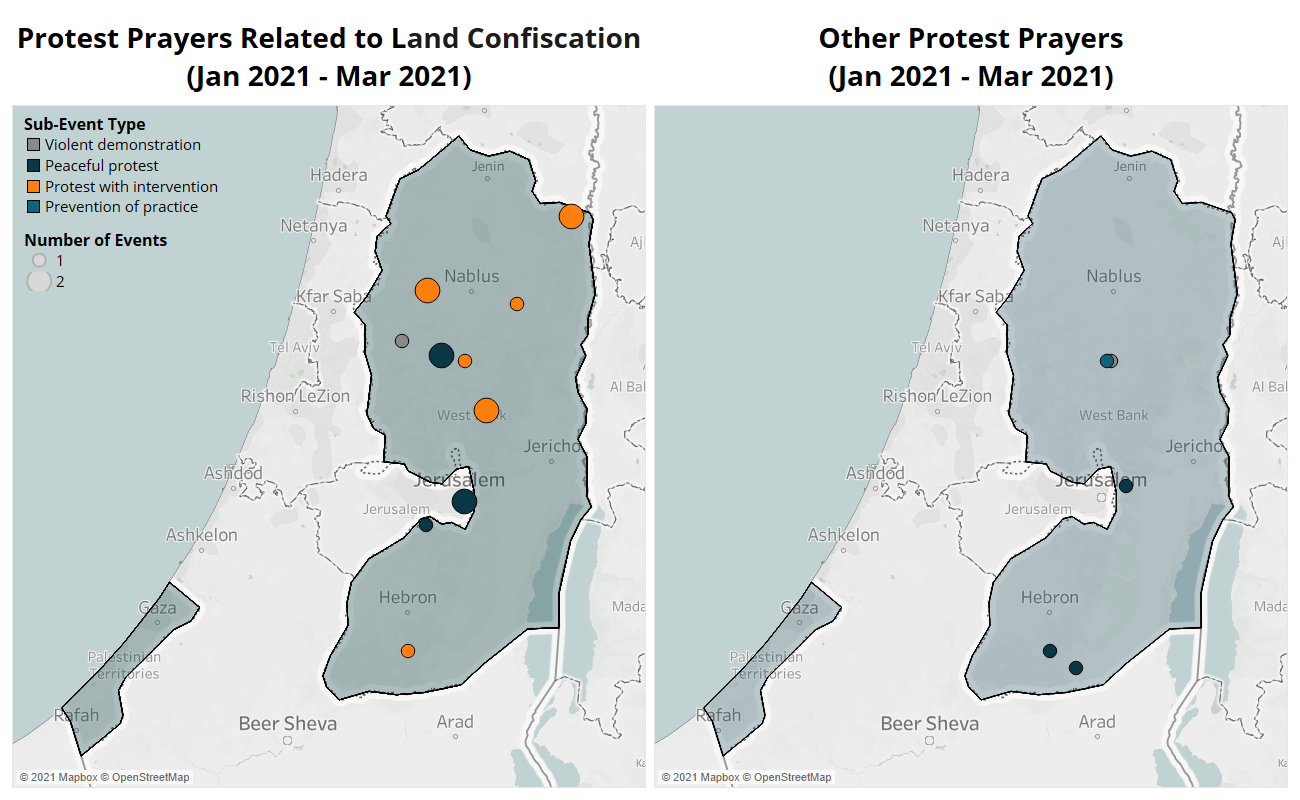

Religious rituals are performances that can assume different meanings depending on the identity of the performer, the audience, the type of ritual, and the place of worship. In Palestine, “prayers of contestation” are an example of how political and religious language can blend together and articulate “new symbolic spaces for contesting the status quo” (Fischer, 2019). “Praying political” is not a new trend, and it is not specific to Palestine (Fischer, 2019). The role of mosques and Friday prayers in Islamic mobilization across the Middle East and North Africa and beyond is widely acknowledged (Butt, 2016). However, since 2017, religio-political prayers have acquired a new dimension for the Palestinian national movement.

On 16 July 2017, following the assassination of two policemen outside Al Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, Israeli security forces installed metal detectors at the entrances of the complex. Palestinian worshippers — mostly Muslims, but also Christians — feared that “Israel wanted to take over Al Aqsa” and took to the streets en masse (Arnaout, 2017). Resistance prayers continued for 13 days, until the police stepped back and removed the security devices. The prayer had a disruptive effect and acquired a political meaning for several reasons: because it was “out of place;” because the Israeli forces (unwillingly) took part in the ritual as an audience (Fischer, 2019); and because the police — caught by surprise — did not dare to challenge the religious performance.

In the ensuing years, the Palestinian national resistance deployed the same strategy on multiple occasions. In 2018, for several months, Friday prayers were held on the Gaza border to demand the return of Palestinian refugees to their land (VOA News, 15 June 2018). In January 2020, a new campaign called ‘The Great Fajr’ deployed dawn prayer protests to contest Israeli visits, security measures, and assaults on Islamic holy sites. The protests focused on the Temple Mount and rapidly extended to Gaza and the West Bank (Jerusalem Post, 18 January 2020). Prayer protests gradually came to express the Palestinian sumud, or steadfastness, symbolizing the refusal to give up their land and accept the Israeli occupation (Shehadeh, 1982).

While this report is based on data collected as part of a program funded by the US Department of State’s Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations, this report is not part of that program. The views expressed in this report are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the United States Government.