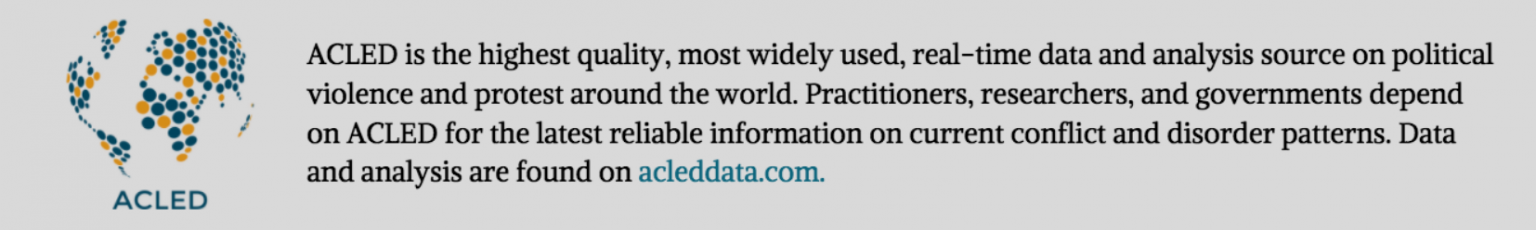

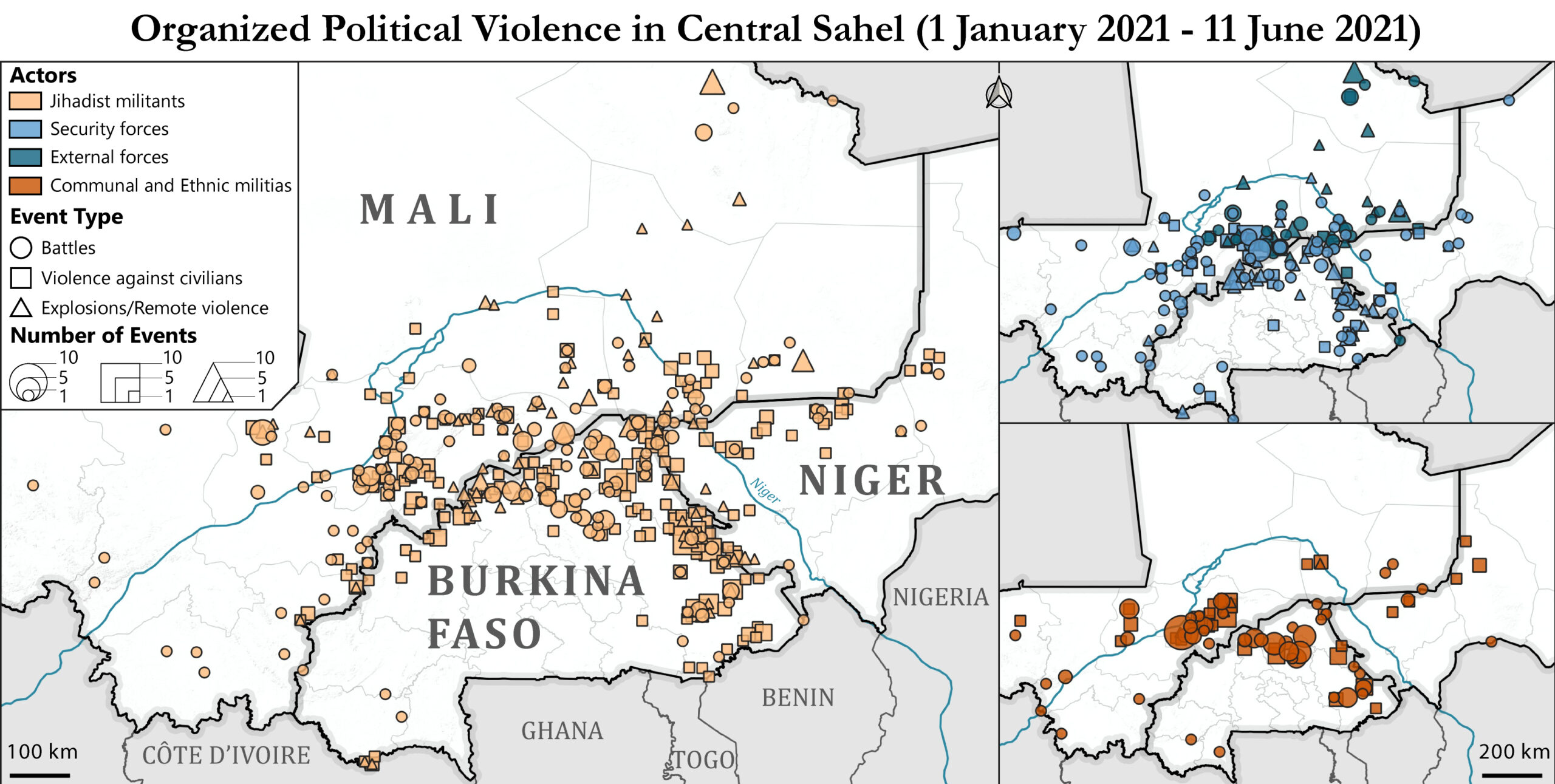

In 2021, the Sahel crisis entered its tenth year. Despite the transnational nature of the crisis, each country has experienced different patterns of violence and transformations in the midst of a protracted conflict. This report looks at the patterns of violence in Niger, Burkina Faso, and Mali. It concludes with a review of the wider Sahel region. The report finds that both the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) and the Al Qaeda-affiliated Jama’at Nusrat Al Islam Wal Muslimin (JNIM) have shifted their efforts to geographic areas beyond the immediate reach of external forces in the face of military pressure in the tri-state border region (or Liptako-Gourma). Renewed engagement in local conflicts has allowed jihadist militant groups to enlarge their scope of action, reassert their influence, remobilize, and gain resources to rebuild. This can be seen clearly in Niger’s Tillaberi and Tahoua regions, the eastern parts of Burkina Faso, and central Mali (see figure below).

Niger: On the Road to Communal War?

It is often assumed that Niger is less overrun by armed groups than its neighbors Mali and Burkina Faso. However, the country faces several challenges. These include the Boko Haram insurgency in the Lake Chad Basin, the Sahelian insurgency led by ISGS in northern Tillaberi, and JNIM activity in southwestern Tillaberi. The rampant banditry that has destabilized the south-central region of Maradi along the border with Nigeria could allow jihadist militant groups to expand their areas of operation (ICG, 29 April 2021). The southward advance of jihadist militants into littoral states, and the increase in jihadist militant activities in countries bordering Niger such as Benin, risk strengthening links between groups in the Sahel and Nigeria. This would in turn shrink the geographical space between the different theaters of conflict.

In 2020, state atrocities amid military operations alternated with mass atrocities by ISGS (ACLED, 20 May 2020). Since early 2021, the country has been marked by significant instability — militants believed to be ISGS have killed an estimated 390 people in various parts of the Tillaberi region and neighboring Tahoua. A series of large-scale killings targeting civilians of Djerma and Tuareg ethnicity resulted in most of the deaths reported.

The number of people killed by ISGS accounts for 66% of all deaths from organized political violence in Niger in 2021, and approximately 79% of the fatalities from violence targeting civilians (as of 11 June 2021). Communities are increasingly resisting the predatory collection of “zakat” or alms, which is a religious obligation in Islam, but is used by ISGS as a pretext for extortion and cattle theft (UNHCR, 13 August 2020). Resistance and self-defense on the part of villagers observed in several locations in Tillaberi was met with relentless reprisals by the militants (RFI, 24 March 2021).

The violence perpetrated by ISGS against civilians is due to various triggers. For example, in February 2020, villagers in Kaourakeri who refused to submit to the militants formed militias and fought with them. In December 2020, villagers in Mogodyougou village beat two ISGS tax collectors to death. In response, ISGS cracked down on residents in both villages, killing more than a dozen people.

During the January 2021 massacres in Tchoma Bangou and Zaroumadareye, there were reports that Djerma villagers, who opposed ISGS, targeted members of the Fulani community with several small-scale acts of violence before the massacres. The Fulani were targeted most likely due to their perceived ties to militants. While many Djerma are also involved in militancy, it is the Fulani who bear the brunt of scapegoating and stigmatization.

While some of the violence is reactive and in response to perceived provocations, other mass atrocities perpetrated by ISGS appear to be instrumental. A massacre perpetrated by ISGS militants in March 2021 in the villages of Bakorat, Intazayene, and Oursanet (Tillia) in the Tahoua region indiscriminately targeted civilians from the Tuareg community, including refugees, and resulted in more than 140 deaths.

Three months earlier, in December 2020, armed Fulani (described by local sources as ISGS) attacked the village of Egareck, also in the Tahoua region. Arab militiamen responded to the attack and drove the attackers away. Anticipating further attacks by ISGS-affiliated gunmen, Arabs and former Tuareg rebels formed a militia in nearby Inkotayan in February 2021. ISGS fighters did not return to Egareck or confront the fledgling militia in Inkotayan, but instead perpetrated the large-scale massacre of civilians in Tillia.

Tillaberi and Tahoua have a long and complex genealogy of violence from rebellions, ethnically based conflicts, and militant and criminal networks. More recently, however, in 2017, the border strip between Niger’s Tillaberi and Tahoua regions and Mali’s Menaka region experienced one of the most intense periods of intercommunal violence between pastoralist communities. The following year, in 2018, the conflict escalated further when Niger decided to outsource security in the border area to the local Malian ethnic-based militias, the Movement for the Salvation of Azawad (MSA) and the Tuareg Imghad and Allies Self-defense Group (GATIA).

French forces cooperated with the same militias through an operationally expedient arrangement called “lash-up” (RAND, 2008). The operations of the ad hoc alliance had adverse effects as violence increasingly took on inter-communal and inter-ethnic proportions. The operations eventually spiraled out of control. As a result, ISGS grew as it mobilized many militants and attracted other factions to the group. A Fulani militant group believed to be involved in the Tillia massacres had joined the jihadist groups in 2018 (ICG, 3 June 2020). It appears that both JNIM and ISGS had competed for their affiliation, although ISGS ultimately won the bid (Menastream, 23 March 2021).

By 2019, ISGS had grown exponentially and carried out some of the deadliest attacks ever perpetrated against Burkinabe, Malian, and Nigerien state forces, becoming the dominant force in the Liptako (ISPI, 3 March 2021). In 2020, however, local and international forces focused efforts on the “tri-state border” region (or Liptako-Gourma), putting ISGS under severe pressure. After waging a multi-front war against state forces and its jihadist rival JNIM, the group appeared to have become a victim of its own success (CTC, 20 November 2020). As ISGS fatalities piled up (Air&Cosmos, 14 April 2021), the group resorted to excessive attacks on civilians in areas under its influence and tried hard to bring the local population to heel. The mass atrocities have been a way for the group to signal to communities that resistance to the group will be severely punished. It also lets authorities in the region and their international partners know that the insurgency cannot be defeated.

While Niger has avoided the internal and rampant ‘militiafication’ of neighboring Burkina Faso and Mali, arming civilians for self-defense appears to be gaining momentum due to ISGS’s disproportionate violence. Paradoxically, some senior ISGS commanders are former militiamen who initially took up arms to protect their communities. ISGS itself mobilized support by making claims of protection against the state and Malian militias.

Budding militias among ethnic Arab, Djerma, and Tuareg communities have now sprung up in sixteen villages in four departments, including Ouallam, Banibangou, Tillia, and Tassara, in the regions of Tillaberi and Tahoua (see figure below). After two large-scale attacks against the Nigerien army in the areas of Tillia and Banibangou, ISGS referred in its propaganda to the fledgling militia formations as “Popular Defense” militias. ISGS accused these groups of collaborating with Nigerien troops and killing people around the town of Chinagodrar (Jihadology, 15 May 2021). However, by pushing further east, ISGS was able to attack unaccompanied Nigerien troops in more vulnerable positions. It has been communalizing the fight by attacking multiple communities and repressing resistance to the group, which could spark a larger and deadlier communal war in which the recent massacres are only the prelude.

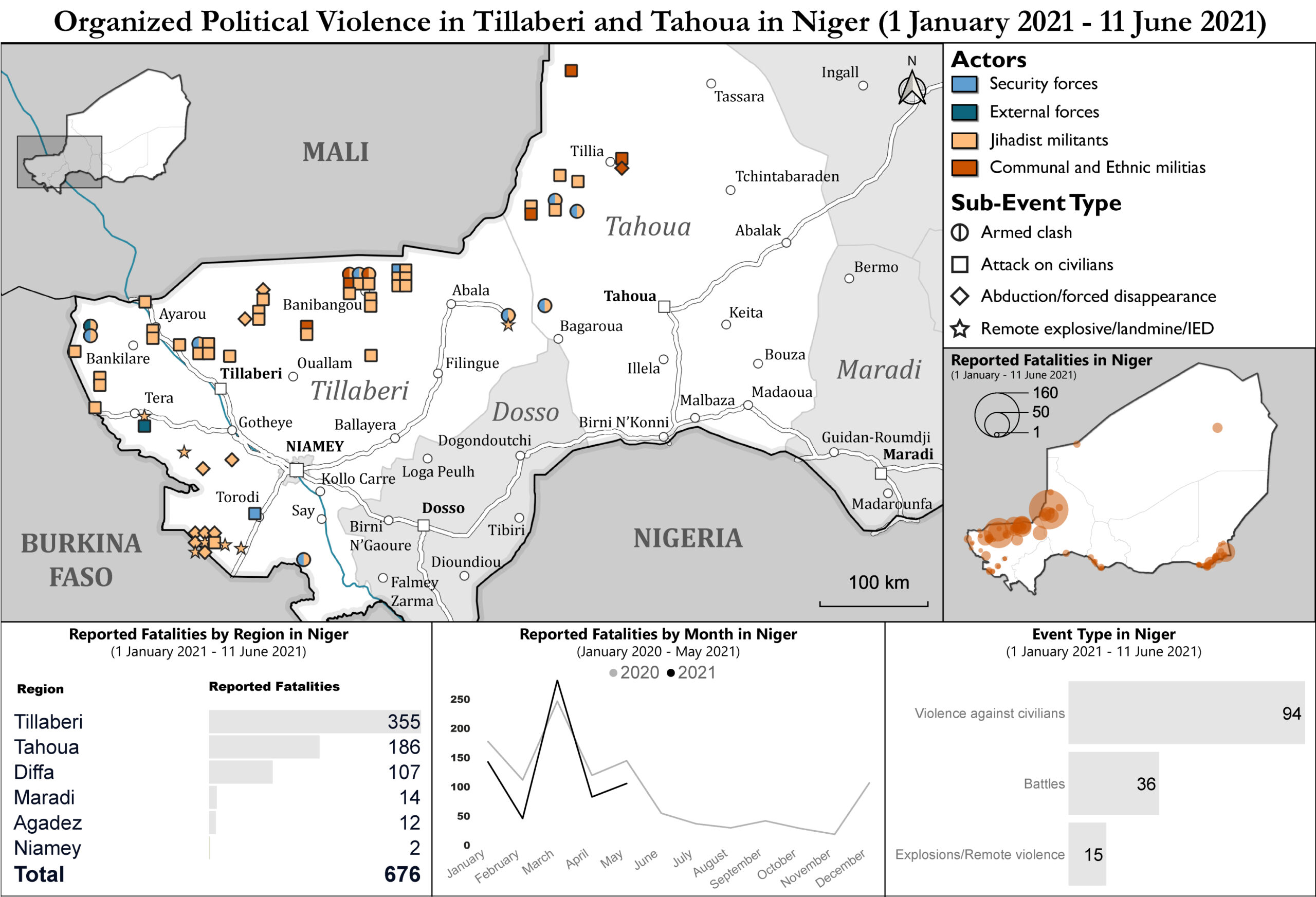

Burkina Faso: Broken Ceasefire and Shifting Frontlines

In contrast to Niger, Burkina Faso has seen a significant decline in conflict-related fatalities since March 2020, when the number of deaths from conflict events in Burkina Faso reached an all-time high (see figure below). Joint operations between G5 Sahel (of which Burkina Faso is a part) and French forces, particularly against ISGS, have remained constant in the tri-state border area. Combined with the fighting between ISGS and JNIM, this has resulted in ISGS losing ground, weakening the group’s capabilities, and limiting its maneuverability in Burkina Faso’s Sahel, Centre-Nord and Est regions. The joint operations have cornered the ISGS in the east of Oudalan and further south in the Seno province, where the group has committed mass atrocities similar to those in Niger.

Negotiations between the authorities and JNIM in early 2020 led to the lifting of the embargo on the town of Djibo, the holding of presidential elections in relative calm, and a general live-and-let-live situation between Burkinabe state forces and JNIM, with limited incidents of deadly violence. The defense and security forces (FDS) did not conduct operations against the group, and JNIM did not attack them in return. This indicated that a ceasefire, albeit a shaky one, was in place. The Burkinabe authorities under President Roch Kabore took a hard line on militancy, at least outwardly. They were sensitive to public opinion, which largely supported the government’s rigid stance. In public, the authorities have vacillated on the issue (RFI, 4 March 2021; TNH, 2021), and by being more secretive, the government has also guarded against failure.

The negotiations that took place in several locations such as Thiou (Libération, 25 March 2021; Sidwaya, 13 May 2021) and Djibo (TNH, 11 March 2021), the release of prisoners from different regions, and the observable outcomes of the negotiations and decline in fatalities in several areas suggest that these smaller negotiations may have been a test run for a broader negotiation effort. The negotiations primarily focused on Soum province, an area that Burkinabe authorities largely ceded during a jihadist offensive in 2019. Military bases in Baraboule,Tongomayel, Nassoumbou, and Koutougou were subsequently overrun and abandoned, and the FDS has not returned since. With no pressure on the fighters in large parts of Soum province, the violence conveniently shifted to other areas.

However, while negotiations may have provided some respite for local populations from the widespread deadly violence, the profound effects of the conflict are deepening, as evidenced by the ever-increasing displacement and humanitarian emergency (Donald Brooks, 22 April 2021). In the meantime, violence has continued at low levels as JNIM attempts to maintain compliance and regulate social conduct through less violent means, including intimidation through threats, beatings, and kidnappings in areas under the group’s influence. The fragile ceasefire apparently collapsed when violence flared up again in several regions.

Beginning in November 2020, in the northeastern town of Mansila, residents’ resistance to JNIM’s harshness in enforcing its social order prompted the deployment of the military (Infowakat, 28 November 2020), after which JNIM imposed an embargo on the town and placed numerous improvised explosive devices (IEDs) along surrounding roads to prevent access. The authorities did not deploy troops to support the population until it became known to the general public that JNIM militants were imposing Sharia law in the town.

Violence erupted in several other locations, including in the Djibo area, where the situation had remained relatively calm since the last major attack on the military camp established in Gaskindé in September 2020. However, tensions between ethnic Fulani and Mossi communities in Kobaoua and Namssiguia resurfaced between late February and early March 2021, when a series of tit-for-tat attacks occurred between JNIM and volunteer fighters (VDP). The VDP are local defense fighters who were predominantly recruited from sedentary communities by the government in 2020 to support the soldiers (Menastream, 11 March 2021). It remains unclear what triggered the resumption of hostilities, although VDP or FDS action cannot be ruled out.

In the northwestern town of Koumbri, the resumption of hostilities appears to have been triggered by VDP actions against members of the Fulani community. In response, JNIM militants have attacked Koumbri three times since the beginning of the year and quickly gained control of the town on 19 and 20 April, while also strengthening their hold on surrounding areas. The Burkinabe army then launched a large-scale operation across the Nord region to dislodge the militants. The army said that 20 militants were killed and four bases destroyed after at least 14 air and artillery strikes and ground operations between 5 and 10 May. The military operation — nicknamed “Houné”, which means “dignity” in Fulfulde (or Fulani language) — was launched only after a series of videos went viral on local social media showing militants in several parades and large gatherings among villagers in the Nord region.

Moreover, the situation in the rural east deteriorated rapidly due to an increase in attacks by JNIM. After a series of attacks in Tanwalbougou, militants killed several members of a joint gendarmerie-VDP unit conducting a search operation in the Singou Reserve. A newly formed anti-poaching unit, accompanied by four foreigners, was ambushed near Pama Reserve, killing three of the foreigners. The event also brought to light the increasing involvement of conservationist non-governmental organizations in enabling the militarization of forest reserves along the borders between Benin, Burkina Faso, and Niger. Conservation security, which tends to reinforce processes of dispossession of local populations from access to land and resources, is associated with injustice and inequality which further fuels militancy and conflict (Hubert, May 2021).

In May 2021, JNIM militants also killed nearly thirty villagers, including VDP, in the village of Kodyel, located in the Foutouri area. The attack was presumably in response to VDP mobilization (AP, 3 May 2021) and abuses against the Fulani community (Twitter, 3 May 2021). A similar attack in December 2019 in the neighboring village of Hantoukoura, in which 14 Christian worshippers were killed, was apparently motivated by villagers’ support for the Koglweogo. Once again, these attacks show that abuse and brutality by all armed actors involved in the conflict are fueling cycles of violence, with ever-deadlier reprisals (ACLED, 31 May 2019).

The deadliest attack since the insurgency began in Burkina Faso occurred on 5 June 2021 with a massacre in the town of Solhan that killed around 160 people. No group has claimed responsibility for the attack; rather, JNIM has denied responsibility and condemned the attack. However, circumstantial evidence and reports point to local groups linked to JNIM, although the mass killing resembles recent ISGS mass atrocities and the group’s behavior in general.

Leaving aside the open question of which group is responsible for the attack, it should be emphasized that JNIM-affiliated groups in eastern Burkina Faso and Yagha have exhibited different behaviors than their brethren in Mali. For more than a year, there has been a disconnect between the center and the periphery within JNIM as an organization, as many attacks are unofficially claimed by local units through videos, photos, and audio recordings. Units operate with a lot of autonomy and are shaped by local contexts and circumstances. The group is not as unified and cohesive as it seems. That said, it could well be that ISGS, but also JNIM-affiliated fighters, carried out the attack even without the consent of central leadership.

The militant groups in Burkina Faso have developed in a geographical space that lies between two competing poles of influence. That is, more broadly, between the more pragmatic JNIM in Mali and the more extreme ISGS in the tri-state border region between Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger. Both JNIM and ISGS compete for the loyalty of these local groups. Thus, the events in Solhan raise questions about both decision-making and shifting allegiances in this violent, competitive, and fast-moving environment in which the attack took place.

More than a year after the launch of the VDP program, the fear of many observers that arming civilians would escalate the conflict and deepen cleavages along ethnic fault lines — between mainly Fulani pastoralists and sedentary communities such as the Mossi, Foulse, and Gourmantche — has become a self-fulfilling prophecy. The high number of VDP fatalities suggests that volunteers have replaced the army on the front lines. Since the beginning of the year, 66 VDP militiamen have been killed, including members of preexisting Koglweogo and Dozo self-defense groups (as of 11 June 2021). The Koglweogo and Dozo are rooted in sedentary communities and absorbed into the volunteer program from which Fulani pastoralists largely have been excluded (Clingendael, 9 March 2021). In comparison to the VDP death toll, only 15 members of the regular armed forces have been killed. In many cases, Burkinabe forces resorted to air strikes rather than ground offensives after deadly attacks, suggesting that regular troops are less willing to engage in more dangerous ground combat.

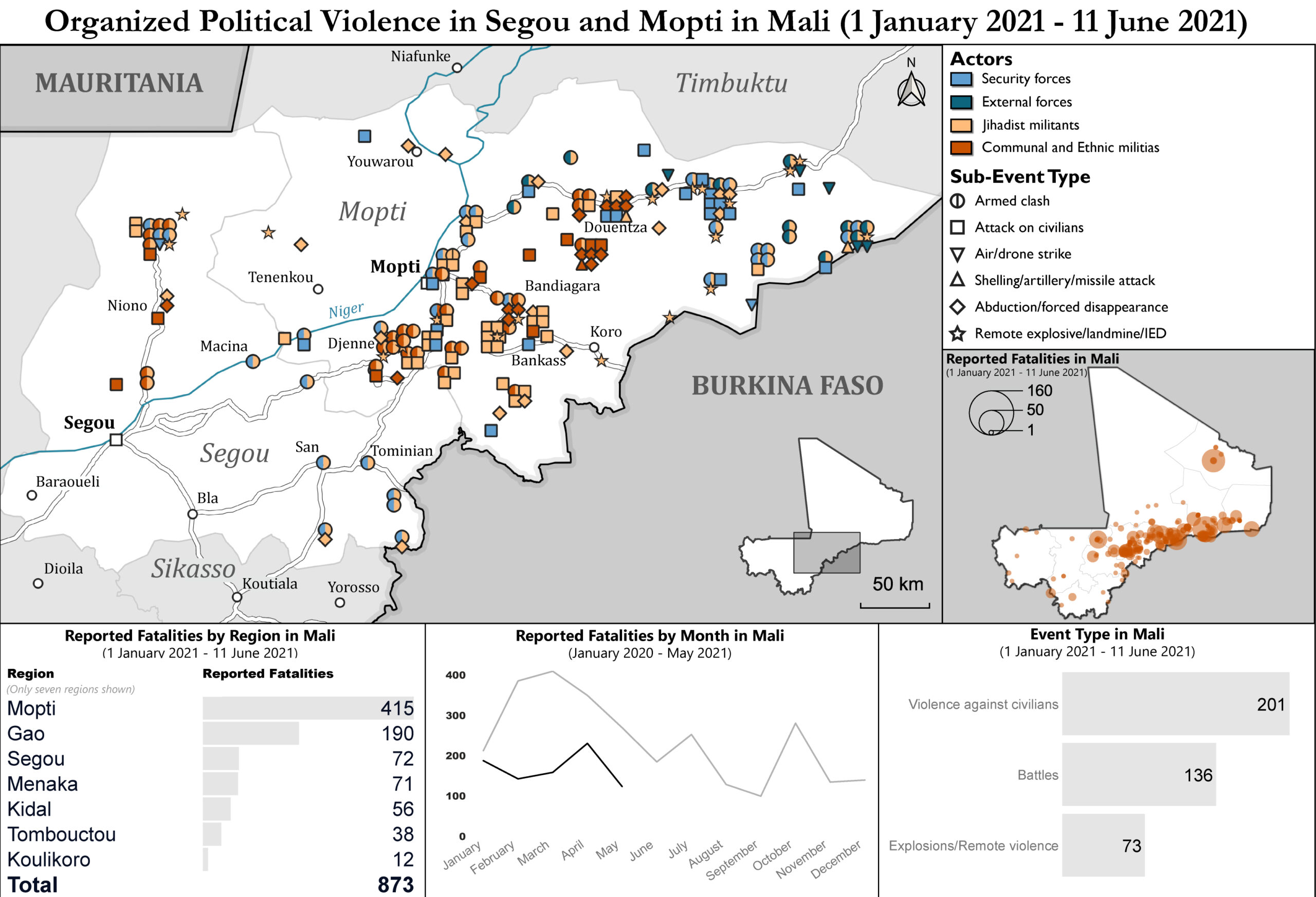

Mali: Extinguishing One Fire at a Time

As the epicenter of the Sahel crisis, the situation in Mali remains fragile. The inter-jihadist fighting between JNIM and ISGS observed during 2020 showed early signs of a weakened insurgency, and the fighting is gradually subsiding. The observable effect of the jihadi-on-jihadi fighting is that the spheres of influence of the two groups are increasingly demarcated. The large-scale French-led military operations that accompanied the launch of Task Force Takuba did not deal a decisive blow to ISGS, but rather only temporarily weakened it. The shift of French forces’ focus to JNIM in October 2020 inflicted significant casualties on the group, yet it continues to wage a multi-front war and maintain a high operational tempo. While the group continued to attack strategic locations in 2021, it also lost key battles against peacekeepers in Aguelhok and Malian forces in Konna. In the Aguelhok attack on 2 April 2021, JNIM suffered possibly its heaviest losses in an offensive operation.

The deadliest attacks on Malian forces to date in 2021 were perpetrated by JNIM on 3 February 2021 in Boni and ISGS on 15 March 2021 in Tessit. Both attacks cost the combatants dearly as Malian and French forces are now better able to respond and coordinate. Local forces still remain vulnerable, though, when operating unaccompanied. However, allegations of misguided French airstrikes, as in Bounty (UN, 30 March 2021) and Talataye (RFI, 26 March 2021), and negligence of human rights abuses by local partner forces continue to discredit France’s efforts to combat militancy in the Sahel. In 2020, Malian state forces killed more civilians than jihadist militant groups and committed more human rights abuses in three of the four quarters of the year, as shown by ACLED and United Nations data, respectively (MINUSMA, March 2021).

Mali shares two key commonalities with its neighbor Burkina Faso. It is challenged by multiple focal points of conflict and engages in a logic of negotiation with jihadist militant groups, although the involvement of the Malian state has varied from case to case. In October 2020, Malian authorities secured the release of the late Malian opposition leader Soumaila Cissé in a prisoner exchange (RFI, 5 April 2021). About a dozen of the released prisoners are from southern Mali, which may partly explain why JNIM has strengthened its positions in Sikasso Region, where jihadist militant activity has surged. On 1 June 2021, militants detonated explosives for the first time in the Sikasso Region to destroy a town hall under construction in the village of Boura. Six months into 2021, militant activity in Sikasso has surpassed the previous year’s total.

In the central region of Mopti (Dogon Country), JNIM engaged in both violent and nonviolent actions against Dogon communities (see figure below). They posed as a mediator between Fulani and Dogon communities to undermine the influence of the ethnic Dogon-majority militia Dan Na Ambassagou and the presence of state forces in the region. The group’s military efforts in Dogon Country became more apparent in late 2019, manifesting in a methodical approach to controlling the area that culminated in a double attack on army and gendarmerie positions in the major town of Bandiagara in February 2021.

A conflict between Bambara and Fulani communities has also been raging in the neighboring Segou region since October 2020, accompanied by an embargo imposed by militants of Katiba Macina (part of JNIM alliance) on the predominantly ethnic Bambara village of Farabougou. After protracted negotiations that failed to bring an end to the fighting, the extra-governmental High Islamic Council of Mali (HCIM) finally succeeded in reaching a ceasefire between the warring parties in April 2021 (Mali24, 18 April 2021).

Once the fire in Farabougou was extinguished for the time being, another flare-up occurred in Djenné, where a peace agreement between Donso militiamen and Katiba Macina that had been in place since August 2019 broke down. An estimated sixty people were killed in fighting that was concentrated in the communes of Femaye, Derary, and Soye in April 2021.

The Malian state is unable to control the various flashpoints in central Mali and the advance of militants in the southern regions due to the prevailing operational weakness of the Malian Armed Forces (FAMa). Disruptive politics in the capital Bamako have strained Mali-France relations and led to disharmony in the strategic military partnership following a second military-led coup in May 2021, nine months after the first in August 2020. As a result, French President Emmanuel Macron threatened to withdraw French troops. France also temporarily suspended joint military operations and cooperation with Mali, depriving Mali of crucial air cover and intelligence capabilities.

The Sahel Region: A Ripple Effect

The large-scale joint military operations by French and G5 Sahel forces have focused on the tri-state border region, an area of strategic importance. They have certainly loosened the grip of jihadist militant groups and temporarily weakened their presence in the area. However, it is evident that over-concentration creates a ripple effect as these groups regroup and resume fighting elsewhere. This is particularly pronounced in the case of ISGS, which has become the deadliest armed group in the central Sahel since 2019. Five months into 2021, the group has already caused the highest civilian death toll by a single armed actor in Niger in any year recorded by ACLED. With the Nigerien state unable to contain ISGS violence, the local population has had little option but to arm itself, which could lead Niger down a path of escalating interethnic violence similar to that experienced by neighboring countries Burkina Faso and Mali in recent years.

The steadily growing jihadist influence in eastern Burkina Faso has further exposed neighboring Benin to the prevailing militant threat. The proximity of its northern borders to the presence of jihadist groups has exposed Benin to jihadist movements and their economic activities (Clingendael, 10 June 2021). On 25 March 2021, an armed confrontation between park rangers and JNIM-affiliated fighters occurred as far as 70 kilometres inside Beninese territory.

In the southwestern parts of Burkina Faso, the jihadists have become more aggressive toward the local population (Infowakat, 20 May 2021), as they seek to consolidate their sanctuary and expand in the north of Ivory Coast (ACLED, 24 August 2020). For instance, in the past two months, Ivory Coast experienced its first four IED attacks. Previous research focusing on other areas in the central Sahel showed that a shift to the use of IEDs and landmines is associated with territorial contestation by jihadist groups (ACLED, 19 June 2019). This comes as armed attacks are also on the rise in the far north of Ivory Coast. As shown by developments in southern Mali’s Sikasso Region and in the east and southwest of Burkina Faso, as well as by the spillover into Ivory Coast and precursor activities in Benin, the militant advance southward has continued and intensified.

The number of militants killed in offensive military operations from early 2020 to date in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger is estimated at over 1,400 (as of 11 June 2021). However, the increasing influence of jihadist groups and the strong resurgence of militant activities demonstrate the limitations of such a measure to gauge effectiveness and success. The over focus on the Liptako-Gourma tends to lead to the neglect of many other areas where jihadist militant groups are increasingly entrenched or expanding their operations. Instead, jihadist groups target their local opponents such as the VDP, Donso, Dana Ambassagou, other militias, or the communities these groups claim to represent.

The rampant displacement and humanitarian crisis further show that conditions are far from being alleviated. JNIM, in particular, has shifted gears to exacerbate the situation in Burkina Faso, increasingly employing tactics which, by and large, pertained to ISGS, including mass atrocities, forced displacement, and public executions. ISGS has recently begun to implement its version of governance through harsh justice by amputating thieves’ hands. This occurred in May 2021 at the weekly market in the village of Tin-Hama in Mali and in the village of Deou in Burkina Faso.

While local peace agreements — in the absence of a global effort — provide local populations with at least a temporary respite from violence, they tend to be fragile and difficult to sustain in the longer term. As has been shown in both Mali and Burkina Faso, broken agreements and ceasefires have been followed by even more deadly cycles of violence. The fact that agreements are often preceded by intense violent coercion suggests that they are best understood as a nonviolent way for militants to achieve their goals by building legitimacy and trust and filling the role of governance actor. A general drift toward disengagement by the states and incoherence within the French-led counter-terror alliance have provided an opening for the JNIM and ISGS to continue their expansion in the region.