Religious repression is often targeted at individuals and groups that express religious behaviors or religious affiliation (Fox, 2016; Sarkissian, 26 May 2015). However, repressive acts can also be directed at imposing a coercer’s religious values regardless of the victim’s religious affiliation (or lack thereof). ACLED-Religion captures this type of religious repression under the ‘imposition’ religious context (ACLED-Religion Codebook, 2021). Critically, religious imposition does not delineate specific repression victims. Indeed, a perpetrator can impose their values on believers of a different religion, on “religiously unaffiliated” or non-practicing individuals (Pew Research Center, 18 December 2012), and on individuals practicing the perpetrator’s religion differently.

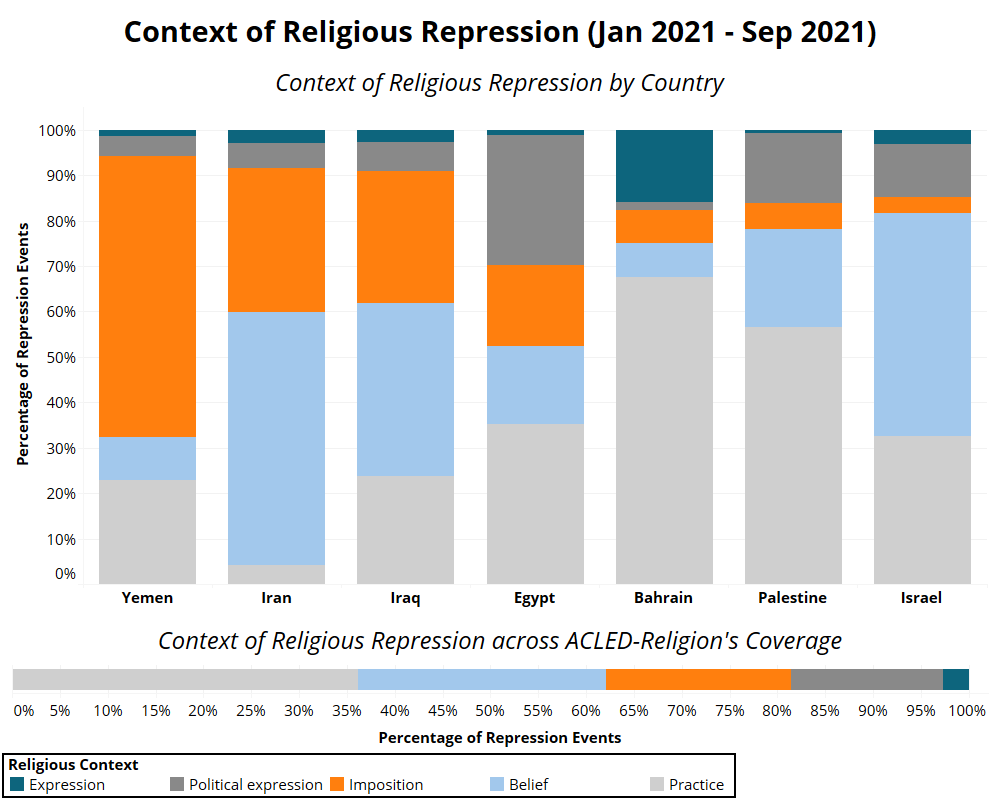

Imposition events account for around 20% of the repression events captured by ACLED-Religion between January and September 2021, distributed disparately across the seven pilot countries covered by the project. Whereas imposition is statistically minimal in Bahrain, Israel, and Palestine (under 10%), it constitutes a significant percentage of religious repression in Yemen, Iran, Iraq, and Egypt (see image below).

This report examines imposition trends in Iran and Houthi-controlled areas of Yemen, which share several structural features. Firstly, both regimes endorse a form of Shiite Islam and are politically aligned under the banner of the so-called ‘Axis of Resistance.’ In addition, they seem to be enforcing similar cultural policies. Similarities and differences in imposition trends in Iran and Yemen can be explained as a result of three main factors: the strategic interests of each country’s political elites; the type of coercive means available to each regime; and the interplay between political and religious environments. Also registering a significant amount of imposition events, Egypt and Iraq serve as useful comparisons in understanding the broader context of religious imposition patterns.

Across the countries considered, three general trends are apparent. State forces are by far the main coercer in imposition events, with the exception of Iraq. Although Islamic values are the main object of imposition, coercion is often justified by vague notions of ‘immorality,’ ‘debauchery,’ or ‘blasphemy.’ Lastly, in all countries except for Yemen, the values object of imposition are mainly traceable to the Islamic duty of ‘commanding right and forbidding wrong.’

Iran

The duty to assume a proactive role in imposing ‘right’ moral values is codified by the Islamic religion in a principle named in Arabic al amr bi al ma‘ruf wa al nahi ‘an al munkar. This expression can be translated as ‘commanding right and forbidding wrong’ from several Quranic verses, though the substance of ‘rights’ and ‘wrongs’ is left undefined. Nonetheless, all the major Islamic sects acknowledge the sensitivity of a few issues — wine, music, and the conduct of boys and women — that constitute the core of a ‘universal’ Islamic morality (Cook, 2009).

In Iran, ‘forbidding wrong’ is a constitutional principle (Article 8) that played a foundational role in the development of the Islamic Republic. Since 1979, the regime has selected a few “signature cultural issues” to publicly represent its abidance to Islamic principles and rejection of the Western “cultural assault” (tahajom-e farhangi) (Farhi, 2005; Rastovac, 2009; Farsoun and Mashayekhi, 2016). These cultural policies have continued in contemporary Iran, with a bill passed in 2010 also setting out the legal framework for the exercise of the ‘forbidding wrong’ principle (Library of Congress, 1 July 2010). ‘Forbidding wrong’ is currently a constitutive duty of most Iranian military and security units, including the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (Aarabi, February 2020). The regime has also established ad hoc authorities to enforce Islamic morality, such as the notorious Gasht-e Ershad (or Guidance Patrols), which is tasked with ensuring women’s observance of the hijab in public (Home Office, November 2019). Since 2006, police forces have also been complemented by special ‘Commanding Right and Forbidding Wrong’ units that aim at curbing un-Islamic behavior through ‘verbal warnings’ (US Department of State, 6 March 2007). From 2020, these units have also been supported by a dedicated branch of the judiciary, and their number and scope have been recently expanded (YJC, 5 October 2020; INW, 28 January 2021; INW, 1 March 2021).

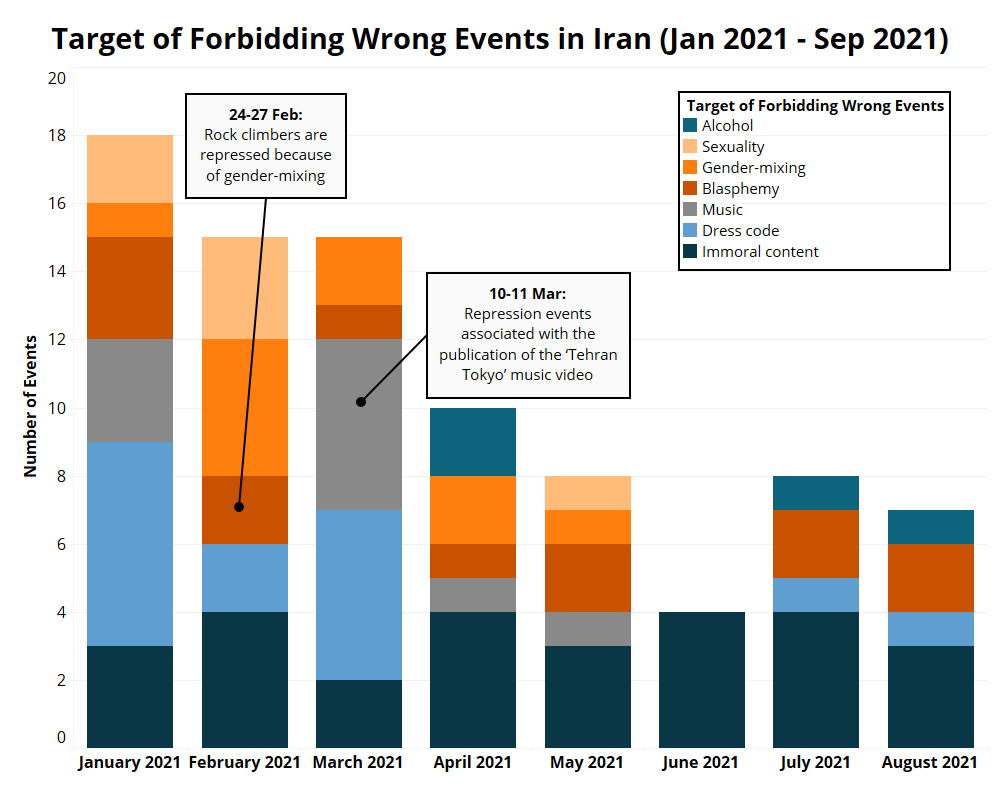

Between January and September 2021, ACLED-Religion captures 98 imposition events in Iran. More than 87% of these events are related to the regime’s effort to forbid ‘wrong.’ Such events target ‘signature cultural issues:’ women’s conduct, gender-mixing, inappropriate musical and visual content, immoral expression, and other aspects (see figure below).

Repressive efforts are overwhelmingly conducted by organs of the state — state forces are the perpetrator in over 93% of the imposition events and judicial harassment is by far the most common form of repression (over 77%). Notably, the Guidance Patrol and ‘Commanding Right and Forbidding Wrong’ units are rarely recorded as perpetrators, potentially because they are mostly included under the umbrella of regular ‘police forces.’ Repression is also conducted on the societal level, but on a smaller scale — ACLED-Religion only records six events involving civilians and clerics as perpetrators under the ‘forbidding wrong’ banner. Overall, imposition events are characterized by a downward trend reaching its lowest in June — the month of the presidential elections — and by a slight rebound in July and August (see figure above).

The Islamic religion is rarely cited by state authorities to explicitly motivate the suppression of alleged ‘wrongs.’ Rather, more than 63% of the imposition events are justified by vague notions of ‘immorality’ or insults against ‘sanctities.’ The specific imposition of Twelver Shiite Islam — the religious denomination officially endorsed by the state — is even rarer, with only four events recorded. Meanwhile, most non-‘forbidding wrong’ imposition events are connected with the repression of political dissent under charges of moharebeh (War against God) and mofsed-e-filarz (spreading corruption on earth) (Minority Rights Group International & Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights, June 2020).

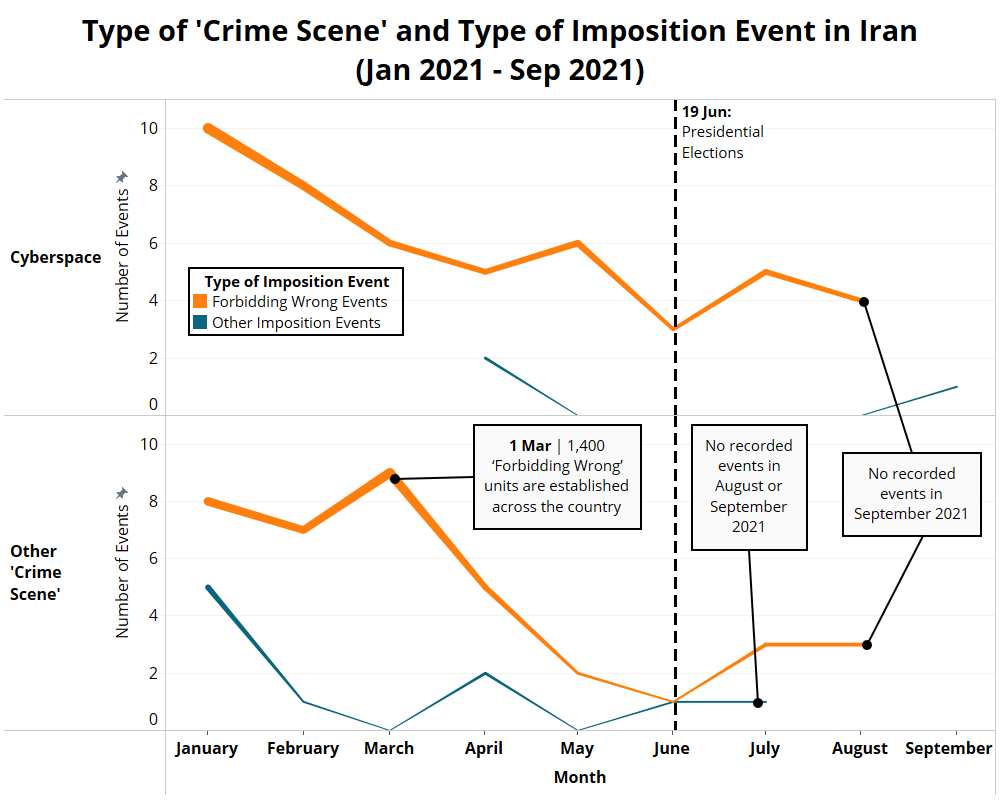

Notably, the patrolling of cyberspace and communication networks plays a fundamental role in imposing state-sanctioned moral values. Since 2007, the Iranian regime has monitored mobile phones and multimedia messages in an attempt to control new technologies (Foreign Policy, July/August 2007). In 2009, Law no. 71063 on Cyber Crimes defined the legal framework to monitor internet and social media, and outlined punishments for “publishing materials deemed to damage ‘public morality’” (Official Gazette, 26 May 2009). In 2011, a new Cyber Police unit, also known as FATA, was established to enforce these directives. ACLED-Religion data clearly reflect the role of cyberspace as a ‘crime scene’1Cyberspace as a ‘crime scene’ is an expression coined by Hossam Bahgat in the Egyptian context. It refers to the role played by social media and online content in exposing private behavior that is later suppressed by state forces (Bahgat, 2004). in exposing alleged ‘wrong’ behaviors in Iran: more than 50% of imposition events are triggered by the publication of content online (see figure below). In addition, over 30% of repression events that ACLED-Religion records in Iran are perpetrated by FATA.

Yemen

A meaningful comparison can be drawn between imposition events in Iran and in the Houthi-controlled areas of Yemen. The Houthis formally adhere to the Zaydiyya, an offshoot of Shiite Islam. However, since the inception of the movement in the 1980s, they have drawn inspiration from the Iranian Islamic revolution, attempting to re-collocate the Zaydi sect within the broader Shiite galaxy (Shuja al-Deen, 7 June 2021). The Houthis’ political allegiance to Iran is underscored by their outright adherence to the ‘Axis of Resistance’ (Al Monitor, 14 April 2020), and their receipt of Iranian military and logistical support (UN Panel of Experts on Yemen, 26 January 2018).

Classic and Mu‘tazilite Zaydi theologies place a fundamental emphasis on the principle of ‘commanding right and forbidding wrong,’ allowing for the use of violence when dealing with ‘wrongs’ (Cook, 2009). In contemporary Yemen, Houthi ideology has reenergized a proactive interpretation of the ‘forbidding wrong’ principle (Lux, 2009). Since the Houthi-Saleh alliance takeover of Yemen’s capital Sanaa in 2014, state institutions have been continuously reformed to serve Houthi political and ideological interests (ACAPS, 17 June 2020). Cultural policies are an integral part of Houthi governance strategies and public morality has been progressively reshaped to reflect sectarian Islamic values (Shiban, 4 December 2020).

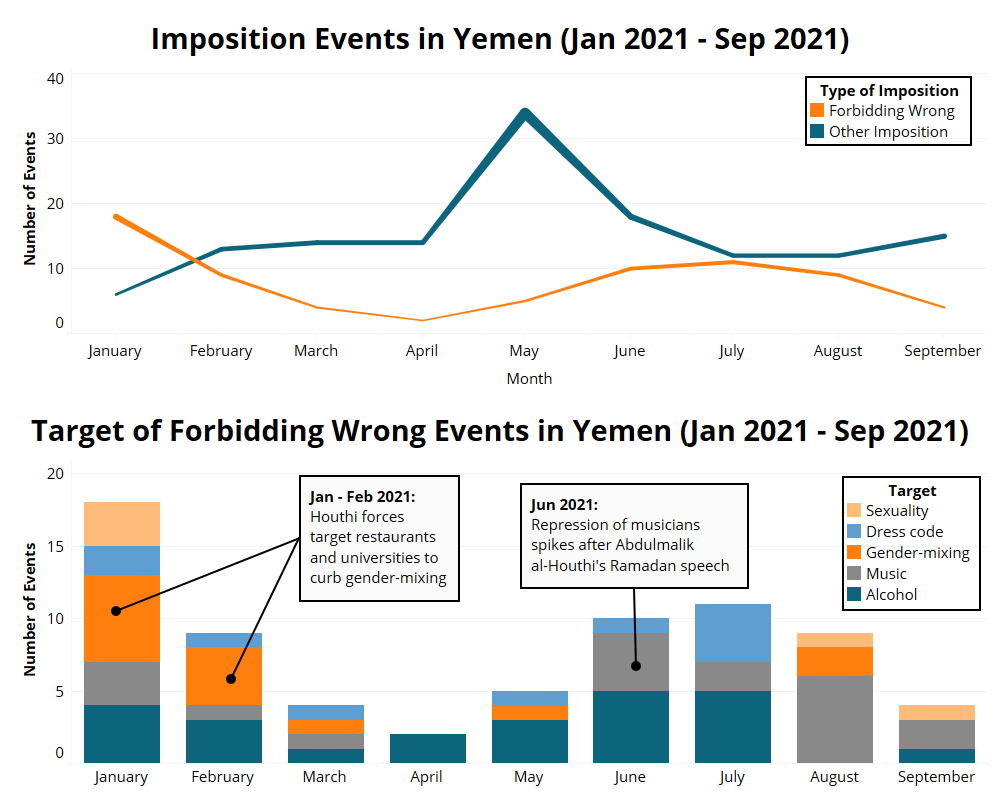

Imposition events are a key part of these cultural policies. Between January and September 2021, ACLED-Religion captures 210 imposition events in Houthi-controlled Yemen. Compared to the trends observed in Iran, three factors stand out. Firstly, the role of cyberspace as a ‘crime scene’ is negligible in Yemen. ACLED-Religion only records one event triggered by the publication of online content. This can be partially explained by the number of internet users in the country — one of the lowest in the MENA region (ITU, 2021). The lack of a specific legislative framework and cybersecurity units also likely contributes to lower internet monitoring.

Secondly, change to religion law/policy events are the main form of imposition that ACLED-Religion records (over 36%). This figure points to the ongoing effort of Houthi authorities to reshape state institutions and public morality through legislative means. This is in contrast with a more consolidated legislative framework in Iran, where most events reflect the regime’s everyday enforcement of public morality.

A third relevant trend is the widespread recourse to religious language. In Houthi-controlled Yemen, over 79% of events are explicitly perpetrated in the name of the Islamic religion. This can be explained by two main factors. Firstly, it reflects the prominence of Islamic discourse in a country where non-Muslim religious minorities are barely recognized and represent a negligible percentage of the population, numbering around 2,000 Baha’is, less than 40 Jews, less than 3,000 Hindus, and a minimal number of Christians (Almahfali & Homaid, 2020; Minority Rights Group International, January 2018; US Department of State , 12 May 2021). Secondly, it accounts for the high number of events characterized by the explicit imposition of Houthi ‘sectarian’ ideology.

ACLED-Religion captures 72 ‘forbidding wrong’ events in Houthi-controlled Yemen between January and September 2021. Across these events, the target of repression is similar to what is observed in Iran: gender-mixing, music, dress code, and other cultural expressions. However, the rationale of repression is substantially different. In Iran, private behavior is growing increasingly distant from enforced laws and public morality (Nooshin, 2005). Accordingly, the Iranian regime’s repression is mostly targeting ‘deviant’ or underground behavior, to restate the regime’s Islamic identity. In Yemen, by contrast, Houthi repression is focused on ordinary public behaviors that have been deemed legitimate — and coherent with Islamic morality — just a few years ago, signalling a shift in religious ideology and an effort to reshape public morality.

A case in point is the repression of music. Since January 2021 — and with renewed determination following a sermon delivered by Houthi leader Abdulmalik Al Houthi in Ramadan in May (Al Mashhad Al Yemeni, 22 June 2021) — Houthi authorities have banned secular music at weddings to strengthen “religious identity” (Sana’a Center, 15 September 2021). This prohibition has resulted in a trail of prevention of practice and abduction events targeting traditional Yemeni music and Yemeni singers (see figure below). The Houthis are replacing traditional music in weddings with religious hymns and performances of Houthi zamils (traditional poems) (Yemen Windows, 28 March 2021). Contrastingly, the Iranian regime — after an initial phase of outright censorship aimed at stressing Islamic identity — has progressively lifted restrictions on music. Currently, repression is mostly focused on westernized pop music (Rastovac, 2009).

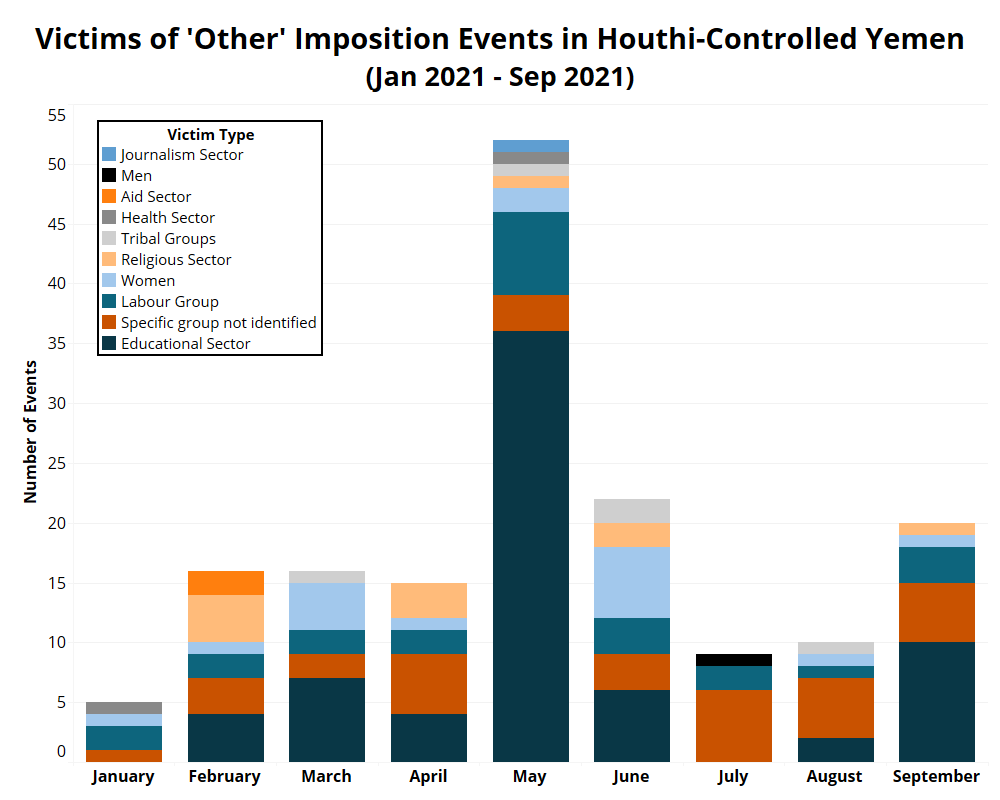

Beside ‘forbidding wrong’ incidents, ACLED-Religion captures 138 other imposition events in Houthi-controlled Yemen. The objective of these repressive practices is twofold: collecting resources to support the war effort, and encouraging commitment to Houthi ideology (for more on these topics, see this ACLED-Religion report). As indirectly shown by the types of targeted victims (see figure below), these events are mainly focused on three domains: the imposition of religious taxes; the reform of the educational sector; and the control of religious discourse. Religious taxes, like the zakat and the khums, are mainly imposed on traders and shopkeepers — groups that are captured by ACLED-Religion under the ‘labor group’ category. Contrastingly, the imposition of Houthi ideology is pursued through the restructuring of school curricula and the systematic replacement of ‘deviant’ imams (Haber, 9 February 2021).

Conclusion

In the countries examined here, most imposition events are directed at enforcing Islamic morality. Nonetheless, in countries like Iran and Egypt, where religious minorities constitute a significant presence, imposition events are often justified through such generic notions of ‘immorality’ or ‘debauchery,’ thus avoiding direct references to Islam. Most imposition events are aimed at enforcing universal, non-sectarian Islamic values as an implementation of the ‘commanding right and forbidding wrong’ principle. However, in each country, a few specific ‘signature cultural issues’ are selectively targeted to reinforce the regime’s identity and cultural policies. In most cases, these cultural expressions are also linked to the country’s recent history. Exemplary cases include the crackdown on TikTok influencers in Egypt and the renewed targeting of leisure activities in Iraq.

The role of the internet varies depending on the institutional framework and the capacity for digital repression. Whereas in Yemen and Iraq ‘deviant’ practices are monitored and tracked in the physical world, most imposition events in Iran and Egypt are triggered by events occuring in cyberspace. This reflects a correlation between dedicated cyber monitoring laws — such as Law no. 71063/2009 and Law no. 165/2018 in Iran and Egypt, respectively — and online repression.

On the surface, imposition patterns might appear to be similar across political and religious environments. For instance, both the Iranian and the Houthi regimes are systematically repressing gender-mixing, music, alcohol consumption, and un-Islamic dress codes. However, at closer inspection, the rationale and means of repression differ considerably across the two countries due to differences in the religious landscape, the strategic interests of the political elite, and the general attitude of the population.

Funding for this report was provided by the US Department of State’s Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations through the Quantifying Religious Repression and Religious Conflict grant. The views expressed in this report are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the United States Government.

© 2021 Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). All rights reserved