New supplemental data for the Philippines add nearly 1,000 events and more than 1,100 fatalities to the ACLED dataset for the period of 2016 to the present, expanding our coverage of the country’s war on drugs. This report analyzes key trends from the data and sheds new light on the drug war’s civilian death toll. Download the data and check the Resource Library for more information about ACLED methodology.

Introduction

Last month, the Philippine Department of Justice (DOJ) completed a review into 52 deaths during police anti-drug operations (Manila Bulletin, 3 October 2021), concluding that criminal charges ought to be levied against 154 police officers (Reuters, 4 October 2021). This marks a rare admission by the Philippine state that it may be complicit in abuses stemming from the war on drugs — which continues to rage on. While the 52 deaths under investigation represent a very small fraction of drug war fatalities, the justice minister announced last month that the DOJ will now look into thousands of other killings that have resulted from anti-drug operations (Reuters, 20 October 2021). Following the announcement, President Rodrigo Duterte stated his admission of full responsibility for the drug war, though “maintained he will never be tried by an international court” (Reuters, 21 October 2021). His comments came as the judges at the International Criminal Court (ICC) approved a formal investigation into possible crimes against humanity committed under his leadership (Reuters, 15 September 2021).

The government admits that over 6,000 killings have occurred during police operations in association with the drug war. Many officers, however, have already been absolved of any wrongdoing in those incidents during internal police investigations. While the DOJ’s plan to review these killings is a welcome step for many victims’ families, analysis of new ACLED data finds that the civilian toll of the war on drugs, perpetrated by the state and its supporters, is much higher than the official figures suggest: at least 7,742 Philippine civilians1In the ICC’s request for an investigation, it noted a broader range of between 12,000 and 30,000 civilian fatalities in connection with the war on drugs, citing estimates by NGOs and local media reports. The estimate based on ACLED data is lower because incidents in which drug suspects were armed, based on reports of police injuries, are not included in this civilian fatality count; while such victims may meet the ICC’s legal definition of a ‘civilian,’ they are not considered ‘civilians’ per ACLED methodology. ACLED data therefore provide a robust but necessarily conservative estimate of the impact of the drug war on Philippine civilians. This estimate nevertheless includes hundreds more civilian deaths than the government’s official count, and marks a higher count of victims than other data collection efforts to date. have been killed in anti-drug operations since 2016, 25% higher than the government’s count, even by a conservative estimate.2Data updated as of 12 November 2021. ACLED data are updated weekly and freely available for download.

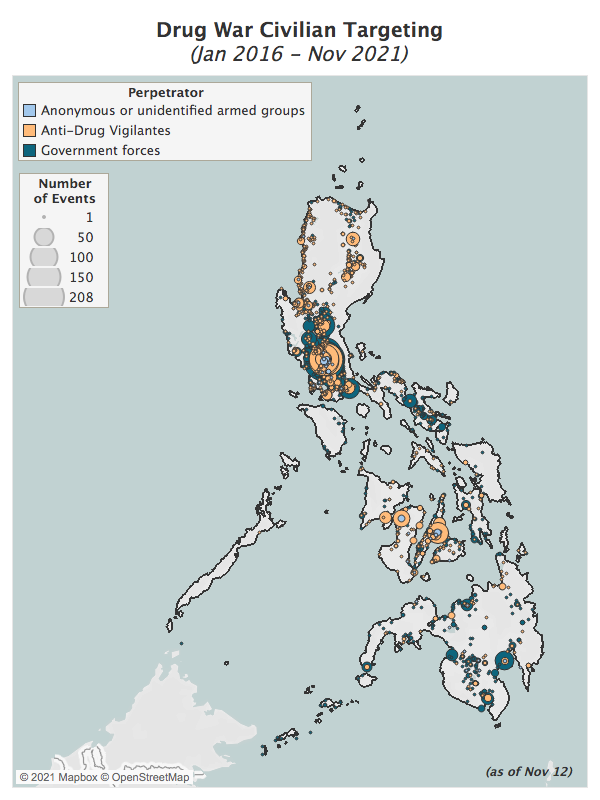

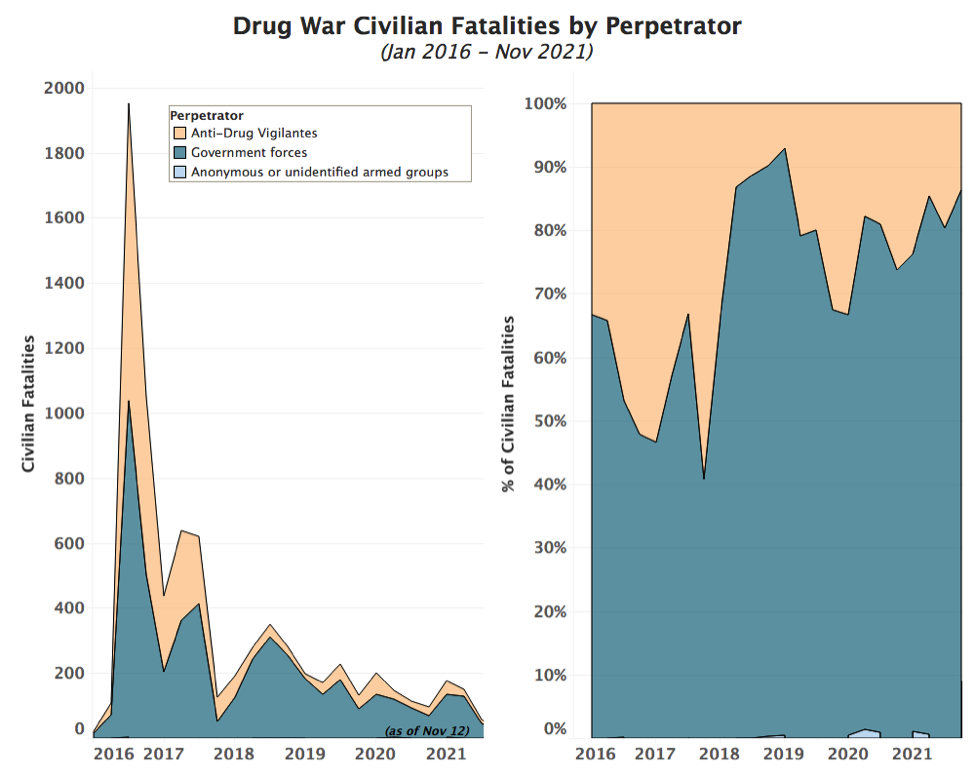

While the overall rate of violence has declined since the height of the drug war in 2016, when Duterte first took office, there have been important changes in trends, including a shift in the primary perpetrators of the war, as well as the geography of violence.

Anti-drug ‘vigilantes’ — largely assumed to have links to the Philippine security infrastructure — were responsible for nearly half, over 48%, of civilian targeting during the early days of the drug war in 2016. Since 2020, however, there has been an upward trend in the proportion of state involvement in drug war violence. The Philippine state has taken an increasingly large role in targeting civilians itself, no longer trying to create distance by ‘outsourcing’ the majority of violence to vigilantes. So far in 2021, state forces have accounted for 80% of civilian targeting in the drug war. The shift appears to be driven by increased scrutiny around vigilantes by the media and international community, as well as dynamics around competing state priorities as the government fights other wars along multiple fronts.

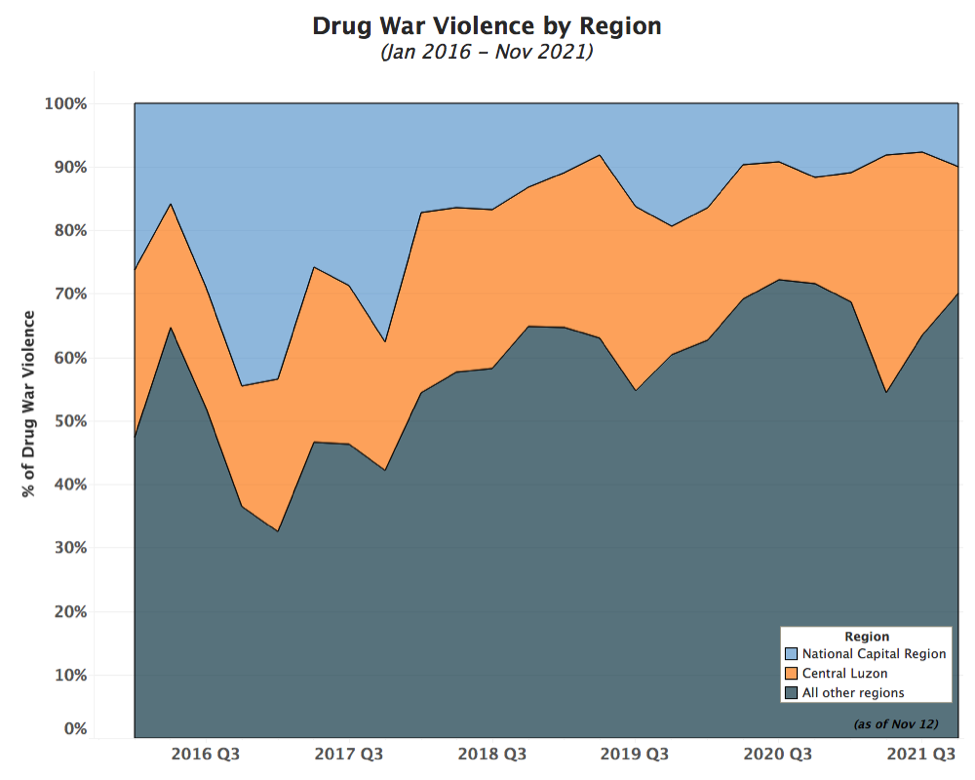

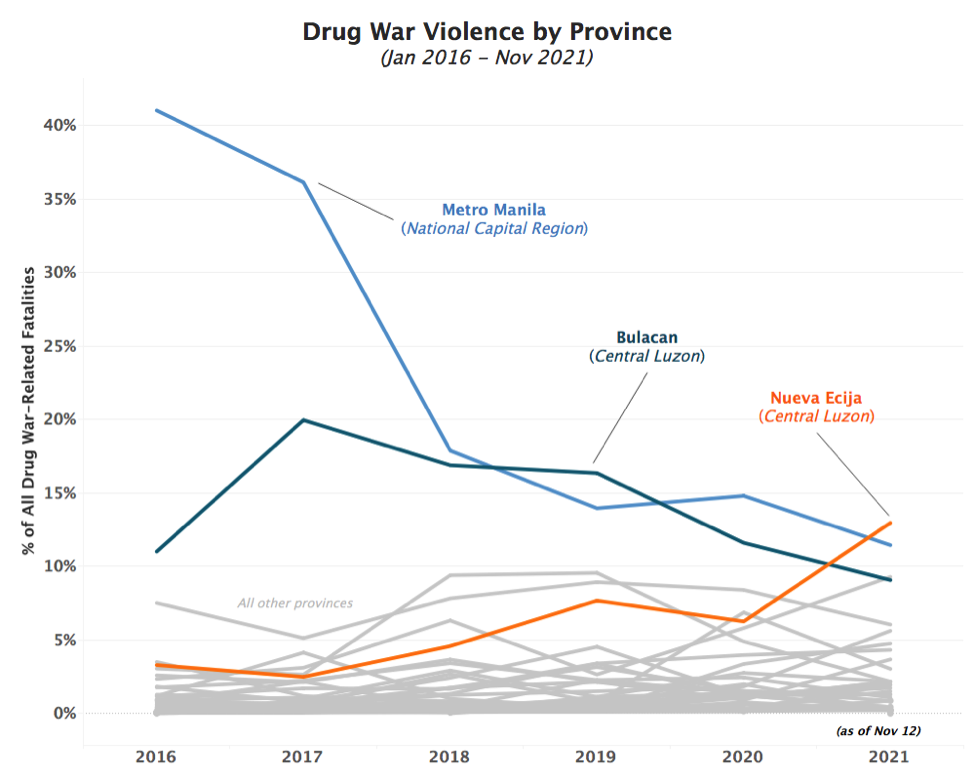

The geography of violence too has shifted, from Metro Manila to Central Luzon, initially coinciding with the reassignment of top police officials from the former to the latter (Rappler, 24 February 2019). More recently, new frontiers have emerged within Central Luzon, with violence shifting from Bulacan province to Nueva Ecija province — now the epicenter of the drug war — as police in Central Luzon continue to be rewarded by the Duterte administration.

These trends, coupled with Duterte’s own admission of culpability last month, underscore the need for an independent investigation into crimes against humanity — especially as the war continues to not only rage on, but also to diffuse beyond Metro Manila.

Information Collection Efforts

As of 30 September 2021, the Philippine government counted 6,201 “persons who died during anti-drug operations” (PDEA, October 2021). The government’s official numbers, periodically published under its #RealNumbersPH campaign on Facebook, only include killings resulting from state operations. These figures exclude ‘vigilante’ killings by non-state actors, which played a significant role, especially in the early days of the drug war, in targeting civilians. This omission has come under scrutiny by human rights watchdogs and media outlets (Rappler, 30 March 2017; ABS-CBN, 6 April 2018; PCIJ, 8 June 2018).

Due to the government’s lack of transparency regarding drug war deaths, there have been multiple independent efforts to track fatalities, though these initiatives are hampered by the inaccessibility of police data and the forced reliance on publicly available media reports (Reuters, 18 July 2019).

The ABS-CBN Investigative and Research Group, which has been tracking drug-related fatalities since 10 May 2016 (the day after Duterte’s electoral victory), records 6,840 fatalities as of 30 June 2021. This figure, based on print, radio, and TV reports, as well as publicly available government data, is not limited to deaths from state operations, but also includes killings by unidentified assailants (ABS-CBN, 16 July 2021).

The Dahas database, produced as part of a collaborative project between the University of the Philippines and Ghent University and the University of Antwerp in Belgium, counts 3,891 fatalities between July 2016 and June 2021. This database, based primarily on news reports from the Philippine Daily Inquirer and other local media sources, is also not limited to deaths from state operations alone, and includes killings by non-state actors like vigilantes (Dahas, 2021; Philippine Daily Inquirer, 23 July 2021).

Meanwhile, in its report during the 44th session of the UN Human Rights Council in June 2020, the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) estimated that at least 8,663 people had been killed in the anti-drug campaign. The figure is drawn from the sum of officially acknowledged deaths in police operations as of 31 January 2020 (5,601) and drug-related ‘deaths under inquiry’ as of 4 February 2019 (3,062). OHCHR stated that at the time this was “the most conservative figure, based on government data,” yet added that it “ultimately cannot verify the number of extrajudicial killings without further investigation” (UN OHCHR, 29 June 2020). Notably, a significant portion of the estimate is drawn from the government’s contested ‘deaths under inquiry’ or ‘deaths under investigation’ category (discussed below). Nevertheless, OHCHR found that “on the basis of information reviewed, the killings related to the anti-illegal drugs campaign appear to have a widespread and systematic character” (UN OHCHR, 29 June 2020).

In the ICC prosecutor’s request for an investigation into the situation in the Philippines, submitted in June 2021, the prosecutor provides an estimate of between 12,000 and 30,000 civilian fatalities in connection with the war on drugs, citing estimates by NGOs and local media reports based largely on the government’s own figures (ICC, 14 June 2021). However, government figures have been confusing due to unclear and changing terminology.

Philippine Government Numbers

While the government has always tracked the deaths of drug suspects in police operations, it also previously tracked and publicized ‘deaths under investigation’ (DUI), a wider category understood to encompass thousands of drug-related, vigilante-style killings. Rappler traced the history of the misleading term, which has led to confusing drug war numbers, in a report in 2017 (Rappler, 30 March 2017). Rappler observed that DUI only began to be tracked and used as a category by the Philippine National Police (PNP) under the Duterte administration. Amid the early confusion, Rappler explained that the term DUI was “the PNP’s way of categorizing deaths in the war on drugs that police officials could not explain because they were outside ‘legitimate police operations’” (Rappler, 20 March 2017). While the PNP initially suggested that DUIs included largely drug-related deaths, over time it has slowly constrained the definition. It later asserted that not all DUIs are drug-related, then later constrained even further to state that DUIs are “murder cases outside police operations, regardless of the motive which [has] yet to be cleared or solved” (Rappler, 30 March 2017). Ultimately, on 9 January 2017, the PNP stopped giving updates on DUIs to police reporters altogether (Rappler, 30 March 2017).3 In August 2016, then PNP Director General Ronald dela Rosa said that such DUIs, without being definitively attributed to vigilante groups, “are the dead who were just found floating along canals, the dead who were dumped along roads with their hands tied and their faces, eyes, and mouths taped. Also those killed by riding-in-tandem, or those who were just shot” (Rappler 18 August 2016). However, a few days later, dela Rosa said that not all DUIs are drug-related (Rappler, 30 March 2017). The PNP later asserted that only part of the DUIs are drug-related. On 10 October 2016, for example, a PNP officer said that only 685 of the then 1,866 DUIs were drug-related. On 2 January 2017, the PNP defined deaths under investigation as “murder cases outside police operations, regardless of the motive which [has] yet to be cleared or solved;” on 9 January 2017, the PNP stopped giving updates on DUIs (Rappler, 30 March 2017).

In a summary of cases, using revised terminology that spoke of “homicide cases” rather than “deaths,” the PNP said that there were 1,370 drug-related “homicide cases under investigation” from 1 July 2016 to 21 March 2017, out of a total 5,824 homicide cases (Rappler, 30 March 2017). Another 894 were said to be non-drug-related, while 3,560 had undetermined motives. Meanwhile, for the same time period, there were 42 drug-related homicide cases already filed in court where the suspect was arrested, while there were 63 such cases where the suspect remained at large. The count for non-drug-related homicide cases already filed in court was much higher, whether for those with the suspect arrested (803) or with the suspect at large (525) (Rappler, 30 March 2017).

Following months of confusion, Rappler said that it made multiple requests for data from the PNP that were clearly broken down by category and presented in a way that was comparable with previously released data. However, Rappler said that such requests went unheeded. This meant that newer data could not be easily compared with older data, due to changing terminology (Rappler, 30 March 2017).

The confusion over these figures underlines the fact that a full picture of the drug war remains elusive, with the government’s alleged underreporting of fatalities serving as a major roadblock. In particular, the changes to the understanding of the term DUI has been a primary cause for confusion. Rappler noted that the figure of around 7,000 drug-related deaths (including killings by both police and non-state actors) had previously been reported by the media as of January 2017. However, when the government launched the #RealNumbersPH campaign in January 2017, it only reported 2,679 deaths related to the war on drugs (i.e. deaths resulting from police operations, excluding all deaths previously categorized as DUI) (Rappler, 18 September 2021).

New Data from ACLED

ACLED data collection on political violence in the Philippines relies on nearly 40 sources, ranging from local newspapers to international media, in both English and Filipino, which researchers review on a weekly basis.4For more on ACLED coding, see the ACLED Codebook and Knowledge Base. The completion of a supplementation project has introduced new data based on information from two major Filipino language sources — Abante and the Filipino version of the Philippine Star5ACLED already includes information from the Philippine Star in English. — to the ACLED dataset, covering the time period from 2016 to the present.6New data are published on a weekly basis via the ACLED website and API. This effort adds close to 1,000 new events to the dataset, and provides additional detail and information to another nearly 900 events already in the dataset, allowing for more detailed analysis. The supplementation project has significantly bolstered ACLED’s coverage of Duterte’s war on drugs, especially the targeting of civilians deemed to be drug suspects by government forces and anti-drug vigilantes. The new data, now publicly available, add over 1,100 additional fatalities to ACLED’s fatality estimate for the Philippines, over 85% of which are civilian fatalities. As of 12 November 2021, ACLED data indicate that at least 7,742 civilians have been killed in anti-drug operations. ACLED’s new estimate aims to contribute to efforts to approximate the full picture of the drug war’s toll on Philippine civilians.

The 7,742 fatality count includes cases in which civilians deemed to be drug suspects were killed by (1) government forces, such as the police or military; (2) anti-drug vigilantes, assumed to have ties to the state (Amnesty International, 31 January 2017; Human Rights Watch, 5 March 2017; ICC, 14 June 2021); or (3) anonymous or unidentified armed groups, often assumed to be supporters of the government, tacit supporters of the government’s drug policy, or even police themselves as part of “secret death squads” (The Guardian, 3, October 2016).7ACLED collects information on fatalities, regardless of whether they are civilians or not, per ACLED methodology. As such, all fatalities stemming from the drug war are included in the ACLED dataset, including the deaths of armed drug suspects who injure police, as well as police who may have been killed by armed drug suspects. While those fatalities are not included in the ‘civilian fatality total’ presented here, ACLED users may still access these data. Similarly, killings of civilians deemed to be drug suspects by other actors — such as a limited number by the New People’s Army (NPA) — are also not included here, despite such incidents often drawing inspiration or support from state policies. The total number of fatalities ACLED records stemming from the war on drugs, which includes these other fatalities as well, is over 8,300 — though this too is a conservative estimate, per ACLED’s deferral to conservative fatality counts. For more, see this primer on ACLED’s fatality methodology. For more on ACLED’s methodology and coding decisions around the war on drugs in the Philippines specifically, see this methodology primer. The estimate based on ACLED data is lower than the broader estimates noted by the ICC because incidents in which drug suspects were armed, based on reports of police injuries, are not included in ACLED’s civilian fatality count; while such victims may meet the ICC’s legal definition of a ‘civilian,’ they are not considered ‘civilians’ per ACLED methodology.8ACLED defines ‘civilians’ as individuals who are unarmed and hence vulnerable (for more, see the ACLED Codebook). ACLED data therefore provide a robust but necessarily conservative estimate of the impact of the drug war on Philippine civilians. This estimate nevertheless includes hundreds more civilian deaths than the government’s official count, and marks a higher count of victims than other data collection efforts to date.

Newly Visible Trends

In addition to new information contributing to civilian fatality counts stemming from the war on drugs, the new ACLED data also point to two important shifts in trends associated with the drug war: (1) a significant shift in the perpetrators of this violence, from anti-drug vigilantes carrying out a large proportion of civilian targeting to the violence increasingly being carried out directly by government forces themselves; and (2) a shift in the geography of this violence, from a focus on Metro Manila to other regions, namely Central Luzon, and to new frontiers within Central Luzon.

Shifts in the Perpetrator of Violence: From Anti-Drug Vigilantes to Government Forces

The vast majority of targeting of civilians considered to be drug suspects has been carried out by state forces, especially the PNP, and by suspected vigilantes. The latter are often described as riding on motorcycles in tandem — hence referred to as ‘riding-in-tandem’ attacks by authorities — shooting victims before driving away.9As such attacks render victims vulnerable, regardless of whether they were armed or not, by not allowing for any sort of reciprocation by victims, the victims of all such attacks are considered to be ‘civilians’ by ACLED. For more on ACLED’s methodology and coding decisions around the war on drugs in the Philippines, see this methodology primer. In some cases, such vigilantes leave cardboard notes next to victims, identifying them as drug suspects.

There are clear ties between anti-drug vigilantes and the state. At minimum, such actors are supporters of Duterte and his drug policies, carrying out attacks inspired by Duterte’s rhetoric. In other cases, the ties between these agents and the state have been more direct, with perpetrators relying on police to secure the perimeter in the lead-up to attacks (ACLED, 18 October 2018), or engaging directly with police in the aftermath of attacks (Human Rights Watch, 5 March 2017). In some cases, perpetrators have admitted to being hired by police to carry out attacks or to plant evidence at crime scenes (Amnesty International, 31 January 2017), or they have been identified as “known police assets” (ICC, 14 June 2021). In yet other cases, the distinction between vigilantes and law enforcement is blurred entirely; some reports suggest that killings attributed to vigilantes were carried out by “members of law enforcement in plain clothes who took measures to make the killings appear as having been perpetrated by private actors” (ICC, 14 June 2021).

Yet law enforcement has also been directly involved and responsible for targeting as well. This has largely unfolded as part of the government’s nanlaban narrative: nanlaban, meaning ‘to have fought back,’ is the narrative often cited by police when justifying drug-related deaths during police operations. Typically, the drug suspect is alleged to have fought back and to have resisted arrest during police operations, in turn ‘forcing’ police to neutralize the suspect. However, the nanlaban narrative has been used as an implausibly common pattern for police ‘buy-bust’ operations (Amnesty International, 8 July 2019). Local police reports often note shoot-outs between drug suspects and state forces, which are then picked up and reported in local media. And while drug suspects are almost always reported as having been armed — in line with the nanlaban narrative — this may not always be true. Photojournalists have noted that victims are often found with multiple bullet wounds, or having been shot in the back or in their hands (suggesting that they were trying to block a bullet and/or displaying they were unarmed), or exhibiting signs of torture. Local organizations have also noted that there is often reason to believe that weapons found next to victims’ bodies may have been planted there after the fact to create staged scenes. The “economy of murder” that has been established as a result of cash reward payouts for every dead body incentivize police to kill — with no payment given for arrests (Amnesty International, 31 January 2017).10For more on ACLED’s methodology and coding decisions around the war on drugs in the Philippines, see this methodology primer.

When reviewing trends in the targeting of civilians considered to be drug suspects, two conclusions are clear. First, it is evident that while the lethality of civilian targeting has declined since 2016, deadly attacks continue: the graph below on the left depicts civilian fatalities from the drug war over time. Hundreds of civilians continue to be killed, even since the height of the drug war in 2016. Second, the data underline the increased role of the government in this targeting: the graph below on the right depicts the proportion of drug war-related civilian fatalities perpetrated by the government (in teal) versus that which has been ‘outsourced’ to anti-drug vigilantes (in orange). While vigilantes were responsible for a considerable proportion of this targeting in the early days of the war, the majority of civilian targeting in recent years has been carried out directly by the state. As Duterte himself has noted: “Why would we hire hitmen when we can hit them legally?” (CNN, 4 August 2016).

This development is likely the result of two primary drivers: (1) the increased scrutiny of vigilantes by the media, and (2) competing state priorities.

Increased Scrutiny of Vigilantes

The war on drugs has been the focus of relentless media coverage, both locally and internationally. A common thread in the media scrutiny and the response of the international community to the drug war11In addition to the ICC investigation, the UN Human Rights Council also adopted Resolution 41/2 in June 2020, requesting the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights to prepare a comprehensive report on the situation in the Philippines, including the war on drugs (UN OHCHR, 25 June 2020). is the acknowledgement of the role that non-state actors have played — so much so that the ICC probe seeks to look not only at killings during the drug war under Duterte’s tenure as president, but to also look further back at killings in Davao City from 1 November 2011 to 30 June 2016, under Duterte’s tenure as mayor there. The ICC has noted that the killings in Davao City were documented to not have only been committed by state actors, but also by vigilantes that were part of the notorious ‘Davao Death Squad’ (ICC, 15 September 2021), similar to the role that vigilantes have played in the more recent drug war.

The increasing scrutiny of the role of vigilantes under Duterte, whether in Davao City or nationally, may have contributed to the scaling back of vigilante activity over time (see right graph above). The government is under immense pressure to prosecute such cases, if only to prove that the local justice system works. After all, the ICC authorized an investigation into the situation in the Philippines because “the supporting material indicates that the Philippine authorities have failed to take meaningful steps to investigate or prosecute the killings” (Rappler, 16 September 2021). Some groups are already calling on the ICC to issue an arrest warrant for Duterte and other officials implicated in the drug war (BusinessWorld, 14 June 2021). With Duterte and other top administration officials facing the prospect of a long-drawn-out legal process, it has become even more important for the government to run a tighter ship with regard to the war on drugs. The police chain of command allows it to do that while continuing to wage this war, as opposed to loosely organized vigilante groups that may prove more unpredictable and more difficult to control.

Competing State Priorities

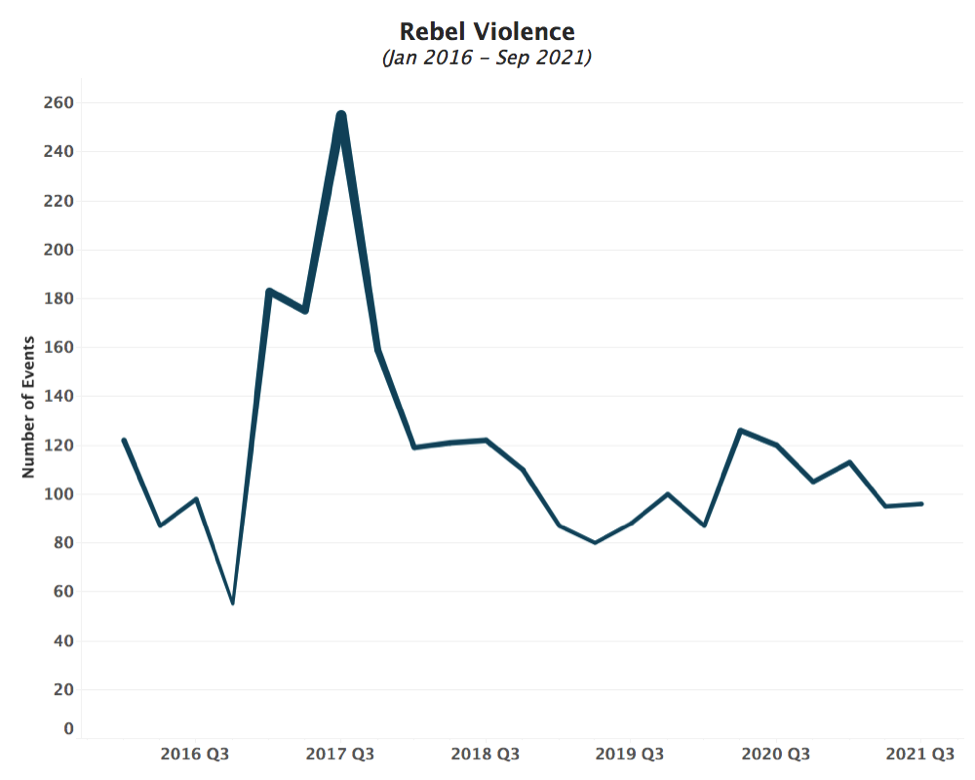

The Philippine state has also been juggling competing wars along multiple fronts for some time. Not only is the state active in the drug war of its own making, but it also continues to battle numerous rebel groups: communists, like the New People’s Army (NPA); Islamist groups, like the Maute Group, as well as a growing Islamic State (IS) presence, such as Dawlah Islamiyah; and separatists, such as the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF). Violence involving such groups was more limited in 2016 (see graph below, which depicts political violence involving all active rebel groups over time), allowing the state to take a considerable part, alongside vigilantes, in anti-drug operations at the start — and height — of the drug war (see left graph above). The state’s role in the war, however, declined in 2017 (see left graph above). This was not only due to Duterte’s ordering the PNP to cease its activities in early 2017 in the aftermath of the senate investigation that took place between August and October 2016 (CNN, 22 August 2016; Rappler, 13 October 2016), but also as rebel violence increased (see graph below). Rebel violence has decreased since 2018, from its height in 2017 during the IS-inspired siege of Marawi City (see graph below); this mirrors the state’s increased capacity since 2018 to carry out much of the drug war-related civilian targeting itself (see right graph above).

Shifts in the Geography of Violence: Metro Manila to Central Luzon

In addition to shifts in the perpetrators of drug war violence, there have also been considerable shifts in the geography of this violence in the Philippines. Since the start of the war in 2016, a considerable proportion of the violence has been centered in the National Capital Region, i.e. Metro Manila.12Incidents in rural areas are likely underreported in the media (The Drug Archive, 2018). ACLED data on drug violence demonstrate that these events occur across the Philippines broadly, but particularly in urban regions, and particularly around Manila. It is likely that a large portion of drug violence events do indeed occur in urban areas. However, there may also be some underreporting in rural areas as media and civil society groups have less of a presence outside of urbanized areas, impacting the quality and quantity of coverage (ACLED, 18 October 2018). More recently, however, violence has diffused from the capital to elsewhere in the country. While drug war violence recorded in the National Capital Region (i.e. Metro Manila) accounted for nearly 45% of the national total at its peak in late 2016 (in light blue in graph below), it now accounts for less than 8% of the national total as of the latter half of 2021. During this time, violence has diffused to other regions of the country, especially to Central Luzon (in orange in graph below).

Metro Manila, as the country’s seat of power, was made the first centerpiece of the Duterte government’s war on drugs. When Duterte, the first president from Mindanao, took his seat in Manila, he exported to the national capital the notorious tactics of his Davao City police, for which he first gained notoriety as the city’s longtime mayor. This was reflected by an exodus of top police officers from Davao to Manila: Duterte installed a group of police officers from his hometown, who called themselves the ‘Davao Boys,’ not only to key positions in the national police leadership, but also to top local posts in the national capital. The most prominent of the ‘Davao Boys’ was Ronald dela Rosa, the former Davao City police chief who was appointed Duterte’s first PNP director general. He was later elected senator as part of the administration slate in the 2019 elections after his stint in the PNP. But other top ‘Davao Boys’ would also see new heights in their careers. For example, Lito Patay, a former police officer from Davao, was handpicked by dela Rosa to head Police Station 6 in Quezon City. He was promoted to the PNP’s Criminal Investigation and Detection Group after dela Rosa commended Patay’s Station 6 for its “highest accomplishment” in the drug war — i.e. its particularly bloody record (Reuters, 19 December 2017).

Amid mounting controversy over the war on drugs, however, such as the massive national outcry provoked by the killing of 17-year-old Kian delos Santos in August 2017 (Rappler, 25 August 2017), the PNP said it would make changes to its execution of the war (Rappler, 28 January 2018). One of these changes was the reassignment of several police officials from Metro Manila to other regions, particularly to Central Luzon (Rappler, 24 February 2019). This shift has coincided with a shift in the concentration of violence from Manila to Central Luzon.

New Frontiers Within Central Luzon

This shift became initially most apparent in 2018 when Central Luzon experienced more drug war violence than the National Capital Region for the first time: 28% of national drug war violence vs. 17%, respectively. The trend, at that time, was driven primarily by violence in the Central Luzon province of Bulacan (in teal on graph below). Notably, however, new ACLED data show that, for the first time, as of mid-November 2021, the Central Luzon province of Nueva Ecija (in orange on graph below) is now home to the most drug war-related fatalities in the country (nearly 13%), the most drug war-related violence in the country (nearly 14%), and the most drug war-related civilian deaths specifically (over 14%) — surpassing both Bulacan and Metro Manila to become the new epicenter of the war.

While the reasons for this shift to Nueva Ecija are not yet clear, Central Luzon had already been established as the bloodiest “killing field” for the government’s war on drugs (Amnesty International, 8 July 2019). In a 2019 report, Rappler noted that the shift of violence to Central Luzon coincided with the reassignment of top police officials from Metro Manila to Central Luzon (Rappler, 24 February 2019). Notably, the chief of the Manila City Police District during the initial peak of the government’s war on drugs, Joel Coronel, was assigned police regional director of Central Luzon. Rappler also identified six other notable police officials who were moved from Metro Manila to Central Luzon during this period (Rappler, 24 February 2019).

The bloody record of the Central Luzon police has been praised and incentivized, both formally and informally. Mere months ago, on 23 September 2021, the PNP recognized the Central Luzon Police Regional Office as the “best police regional office” during an official event in Quezon City (Sunstar, 24 September 2021). In addition, Central Luzon seems to have become a launching pad for higher positions in the country’s security establishment. All previous Central Luzon police regional directors under the Duterte administration went on to occupy higher security positions after their stint in the region.

Aaron Aquino, the very first Central Luzon police regional director under Duterte, who first rose to prominence in Davao City alongside Duterte’s first PNP Director General Ronald dela Rosa, was appointed head of the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA) after Duterte praised Aquino’s bloody campaign in Central Luzon (Reuters, 19 December 2017). Aquino’s successor in Central Luzon, Amador Corpus, was later named the director of the PNP’s prominent Criminal Investigation and Detection Group (CIDG) (Manila Times, 20 November 2018), before being demoted due to a political controversy over accommodations for erring police officers (Rappler, 20 October 2019). Corpus’s successor in Central Luzon, the aforementioned Joel Coronel, was also later appointed CIDG director. The two latest police officials to have occupied the top Central Luzon post, Rhodel O. Sermonia and Valeriano de Leon, were reported to be in the running to be the latest PNP director general (Manila Standard, 3 November 2021), though another official was eventually named to the post (Philippine News Agency, 10 November 2021). In any case, both Sermonia and de Leon vowed to “not let-up” in the police anti-drug campaign during their respective terms in Central Luzon, despite a temporary dip in crime during Sermonia’s term amid COVID-19 quarantine measures (PNA, 19 May 2020; Philippine Star, 15 October 2021). The new Central Luzon police regional director, Matthew Baccay, who assumed his post earlier this month on 1 November, also promised that there would be no let-up in the anti-drug campaign under his watch (Sunstar, 1 November 2021).

Indeed, the Central Luzon police, guided from the top by a rock-solid commitment to the government’s anti-drug campaign, have become a model of perseverance for the Duterte administration’s war on drugs. Such perseverance has been handsomely rewarded by the administration and its security establishment.

Looking Forward

As the end of his term approaches, all eyes are on President Duterte and his handling of the drug war as the DOJ plans to review thousands more deaths stemming from anti-drug operations. Internationally, the ICC formal investigation into possible crimes against humanity looms. Even the recent Nobel Peace Prize awarded to Philippine journalist Maria Ressa for her work in reporting on state violence despite attacks on press freedom in the country points to the emphasis being placed on investigating the ongoing war on drugs (The Guardian, 12 October 2021).

With the impending election, scheduled for May 2022, there is much at stake. Duterte’s presidential mandate will come to an end, leaving many wondering what the future holds for him and his successor. As Duterte can no longer hold the presidency himself, he initially announced his intention to seek the vice presidency — a position elected separately from the presidency — which would have provided him cover and immunity from prosecution for his role in the drug war (New York Times, 27 August 2021). Last month, however, he instead announced his intention to retire from politics, stating that he would not be seeking election (Bloomberg, 2 October 2021). Yet, in another reversal, he announced on 13 November that he would run for vice president after all, before days later on 15 November filing papers instead to run for senator in 2022, making use of a candidate substitution loophole weeks after the regular deadline (Rappler, 15 November 2021). The senate position comes with notable benefits, including privilege from arrests for offenses punishable by not more than six years imprisonment (ABS-CBN, 12 October 2018).

This last-minute frenzy of election substitutions, confusing voters as to who the administration candidates actually are, has left the question of who will succeed Duterte as president even more pronounced. At one point, Duterte’s first police chief was his anointed candidate: in a surprise announcement last month, mere moments before the closing of the regular filing period for certificates of candidacy, Ronald dela Rosa — the same former PNP director general — formalized his presidential bid under a faction of the PDP-Laban,13Partido Demokratiko Pilipino–Lakas ng Bayan Duterte’s political party. He noted that the announcement had been “deliberately kept secret as a tactical move” until the final moment (Philippine Daily Inquirer, 8 October 2021). Not only is dela Rosa a loyal supporter of Duterte, whose position as president would surely keep Duterte safe from prosecution, he himself would have much to lose from allowing drug war prosecutions to occur given his own role as the head of police. The Philippines’ winner-take-all system — where the candidate receiving the most votes wins, without the need for a majority or a runoff election — means that the stakes are high. This is true for Duterte and dela Rosa, who both risk facing prosecution for crimes against humanity. A number of opposition candidates have already vowed to cooperate with the ICC investigation should they win, resulting in dela Rosa admitting to feeling “a little worried” about the probe (Philippine Daily Inquirer, 2 November 2021).

Since then, however, with early opinion polls showing that voters were more receptive of other administration-aligned candidates (Manila Bulletin, 15 November 2021), Duterte seems to be hedging his bets in search of a succession plan that would best protect him and his allies. As such, Duterte’s party made another last-minute change on 15 November, again through the substitution loophole, just two days before the deadline: dela Rosa withdrew his candidacy for the presidency (Rappler, 13 November 2021), with the party instead fielding Senator Christopher ‘Bong’ Go, Duterte’s most trusted aide, for the top post (Philippine News Agency, 14 November 2021).

At the same time, Duterte’s daughter, Davao City Mayor Sara Duterte, filed papers to run for the vice presidency with another party, Lakas-CMD14Lakas ng EDSA–Christian Muslim Democrats — again through the substitution loophole (Rappler, 13 November 2021)15 In the Philippines, the vice president is elected separately from the president, and candidates from different parties may be elected to the two posts and concurrently serve. — only to have the PFP,16Partido Federal ng Pilipinas the party of current presidential election frontrunner Ferdinand ‘Bongbong’ Marcos, Jr., immediately adopt her as Marcos’ running mate (Rappler, 13 November 2021). With seeming tension between the elder Duterte and his former ally Marcos, the president announced on the same day that he would run for vice president against his daughter, who he had wanted to run for the presidency (Rappler, 14 November 2021). However, as noted above, Rodrigo Duterte ultimately switched course and filed papers to run for a senate position by the 15 November deadline for substitutions (Rappler, 15 November 2021), likely after coming to some sort of agreement with Marcos. The tandem between Marcos and Sara Duterte was finally made official on 17 November (Rappler, 17 November 2021).

With so much on the line, Rodrigo Duterte would benefit immensely from an electoral outcome that keeps him, his family, and his top officials at the highest echelons of power: an outcome, for example, which sees him in the senate; his daughter as vice president; his trusted aide Go as president; and/or his daughter’s running mate Marcos as president, with whom he has likely reached an arrangement, resulting in Duterte agreeing not to challenge his own daughter for the vice presidency. Duterte’s presidency has provided him with the very tools he could use to secure such a future. Drug war tactics, employed under the new label of ‘securing the nation against communism,’ are tools that he can use to achieve such a result. “The National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC), established by the Duterte administration in December 2018, [has been] at the center of the network of Facebook pages and groups pushing out red-tagging content” (Rappler, 3 October 2021). ‘Red-tagging’ refers to the act of labeling someone a ‘communist’ or ‘terrorist’ — in effect, putting a target on someone’s back by designating them a threat to the state. In the early days of the drug war, the Duterte administration released a ‘watch list’ containing the names of ‘drug suspects’ who were then targeted by both vigilantes and police. Those ‘red-tagged’ now — largely members of leftist groups and academics seen as opposition (Rappler, 3 October 2021) — are facing similar consequences. The human rights group Karapatan has noted that since the start of Duterte’s presidency in July 2016, 33 red-tagged activists have been killed, often by suspected police or military elements, showing that “red-tagging is akin to a death warrant that brings grave risks to those who had been branded” (Philippine Daily Inquirer, 2 November 2021). Recently, the government’s targeting of activists seems to be taking more and more cues from the anti-drug campaign. Drawing on similar tactics used during the drug war, some police operations against activists have already resulted in deaths in line with the nanlaban narrative so often relied upon as part of the war on drugs (Rappler, 3 October 2021).

As the election draws near against the backdrop of the impending ICC investigation, and worries continue to rise for those in power, tensions will increase. And with the rise in political tensions will be a rise in the threat to civilians, especially those branded as ‘opposition.’ Continued monitoring of these trends, especially the targeting of civilians, will be as important as ever in order to ensure those responsible for abuses are held accountable.

© 2021 Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). All rights reserved.

© 2021 Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). All rights reserved.