Religious celebrations can function as catalysts for religious repression, carrying a potential for state abuses and minority contestation (Hintz & Quatrini, 2020). A focus on Ashura celebrations demonstrates how regimes and believers can choose to respond to this Shiite festival depending on their respective religious affiliations, and how these responses can raise the risk for certain forms of religious repression.

On Ashura, which recurs on the tenth day of the Islamic month of Muharram, millions of Shiite believers across the globe mourn the death of Imam Husayn by reviving the events of Kerbala and staging mourning processions (Nikjoo et al., 22 March 2020).1In Shiite Islam, Ashura is the commemoration of the death of Imam Husayn b. Ali b. Abu Talib during the battle of Kerbala (680 DC) in which he confronted the army of the Umayyad Caliph Yazid (Veccia Vaglieri, 2012). Commemorations continue for 40 days after Ashura, culminating with the Arbaeen walking pilgrimage, in which mourners walk to the Imam Husayn Shrine in Kerbala, Iraq.

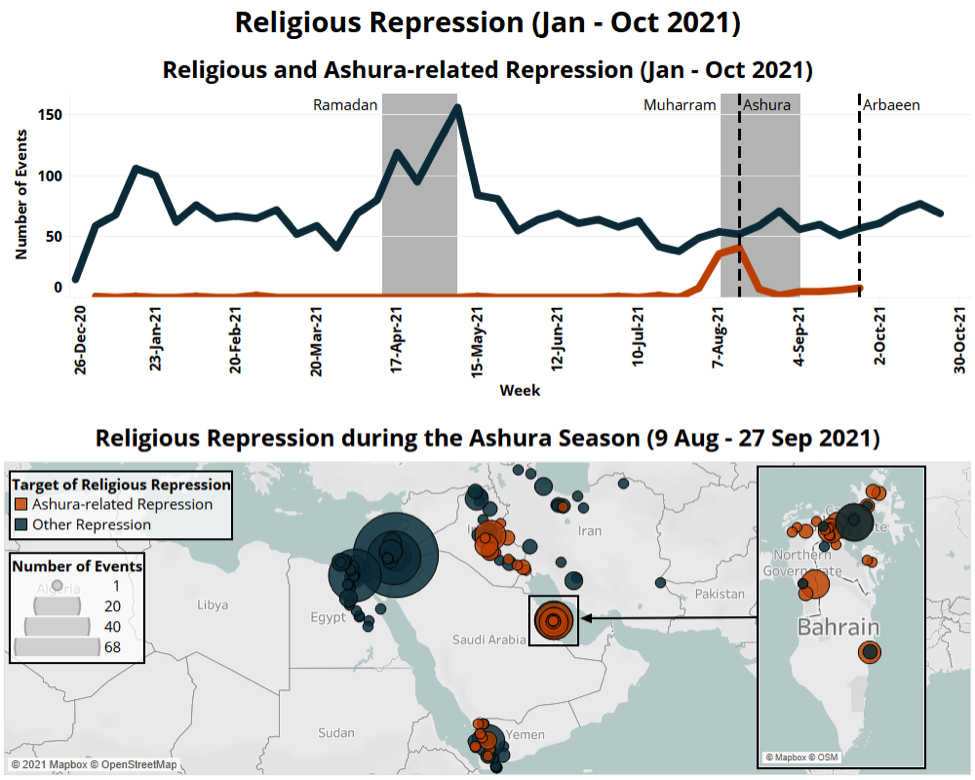

In 2021, ACLED-Religion records a 50% increase in religious repression in the week preceding Muharram (31 July-6 August) compared to the week prior, and a further 58% increase during the first week of Muharram (7-13 August). Notably, most Ashura-related2Ashura-related religious practice is determined based on explicit references to the suppression of Muharram, Ashura, and Arbaeen rites, or to the enforcement of norms and regulations specifically decreed for Ashura season. The estimate of Ashura-related events is conservative, since sources may not explicitly mention the connection between a given repression event and Ashura-related religious rituals. repression events are concentrated in just three countries covered by the pilot project — Iraq, Yemen, and Bahrain (see figure below)3In Iran, where Shiite Islam is both the majority religion and the official religion of the state, only one Ashura-related repression event is recorded: the violation of a Christian cemetery in relation to Ashura rituals. — that have in common the presence of a large Shiite population. In these three countries, Ashura-related repression accounts for 46% of all religious repression events during ‘Ashura season’ (9 August-27 September).4In this report, the period between the beginning of Muharram and Arbaeen (9 August – 27 September) is referred to as ‘Ashura season.’ Across all seven countries covered by ACLED-Religion, Ashura-related repression accounts for around 20% of religious repression events during the Ashura season.

This report examines Ashura-related repression trends in Iraq, Yemen, and Bahrain, three countries that account for over 99% of Ashura-related repression events. Across these countries, the report explores the role of the state in endorsing or suppressing Ashura-related rituals, including their selective use of COVID-19 restrictions. Three main findings are apparent. First, regimes tend to selectively decree and enforce COVID-19 restrictions to control people’s attendance of relevant religious celebrations. Second, differences between the majority population’s religious affiliation and the religion endorsed by the regime are exacerbated during religious festivals and can lead to increased religious repression. Third, religious minorities are a potential target of repression during the majority’s religious celebrations.

Iraq

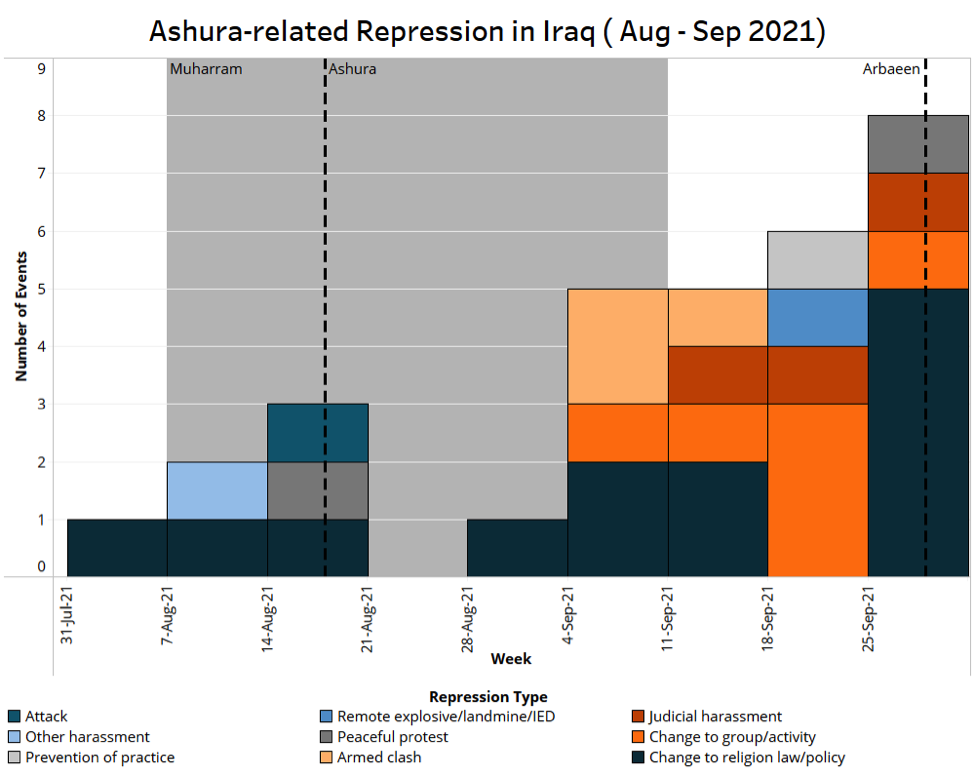

Every year, millions of Shiite Muslim pilgrims march to the Iraqi city of Kerbala to visit the Imam Husayn Shrine and mark Ashura commemorations. In 2021, Iraqi state institutions and religious leaders issued preventive measures to curb the spread of COVID-19 in the lead up to Muharram, which began on 9 August. Health authorities instructed the population to hold mourning rituals in open spaces and participate in the pilgrimage from afar (Al Mirbad, 8 August 2021). The prominent Shiite leader Muqtada Al Sadr suspended Friday prayers and declared attendance at Husayni mournings haram (religiously forbidden) for non-vaccinated people (Al Ahad TV, 5 August 2021; NRT, 15 August 2021). These preemptive efforts are recorded by ACLED-Religion in the form of three ‘change to religion law/policy’ events specifically aimed at limiting Ashura-related religious practice in Iraq (see events before Ashura line in graph below).

However, despite this stance on COVID-19 health risks, the Iraqi government did not enforce pandemic-related restrictions, allowing around six million pilgrims to celebrate Ashura commemorations in Kerbala (The Arab Weekly, 20 August 2021). A similar policy was adopted by state authorities during Ramadan 2021 (for more, see this ACLED-Religion report). This policy is apparent in the lack of ‘prevention of practice’ events before and during Ashura commemorations.

Meanwhile, on the societal level, ACLED records one ‘attack’ event, when an unknown individual stabbed a Shiite worshipper to death while they performed tatbir (ritual bloodletting) in Kerbala. In one instance, an Ashura procession in Najaf (coded as ‘peaceful protest’) was politicized into a demonstration against the normalization of relations with Israel (see graph above).

Despite the symbolic value of the tenth day of Muharram, the Arbaeen represents the apex of Ashura season in Iraq. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the walking pilgrimage of Arbaeen attracted around 20 million Shiite believers per year (Nikjoo et al., 22 March 2020). Pilgrims converged from all over the world to southern Iraq to walk the 80 kilometers separating the holy shrines of Najaf and Kerbala (Nikjoo et al., 22 March 2020). Impending threats to personal safety — such as the risk of Islamic State attacks — barely affected these numbers, as pilgrims viewed ‘suffering’ and ‘risk’ as constitutive parts of the Arbaeen pilgrimage (Nikjoo et al., 23 July 2020).

In 2021, ACLED-Religion records 26 repression events before and during the Arbaeen pilgrimage (see figure above), with the Iraqi government’s endeavors to limit foreign access to the country captured through 11 ‘change to religion law/policy’ events. Iraqi authorities capped the number of visas for the pilgrimage at 80,000 (Shafaq News, 9 September 2021), banning international travel across land borders (for more, see this ACLED-Religion Weekly Overview).5Restrictions on land travel were partially lifted around 25 September, allowing access from the Shalamcheh and Zurbatiyah and ports (Al Sumaria TV, 25 September 2021).

The precarious security situation in Iraq is also reflected in violent events affecting Arbaeen pilgrims. During the Arbaeen pilgrimage, three tribal armed clashes and one landmine explosion impacted Arbaeen pilgrims. In all recorded cases, the tribal clashes were unrelated to Arbaeen and accidentally impacted the pilgrims, causing at least three injuries and two fatalities among them. Six ‘change to group/activity’ events capture security measures imposed on the general population to protect the Shiite pilgrims. In particular, police and military units were deployed to Kerbala, Najaf, Baghdad, and Babil districts between 9 and 25 September and motorbikes were banned in Al Qadissiya. Lastly, a religious procession was again politicized in Kerbala to protest the normalization of relations with Israel.

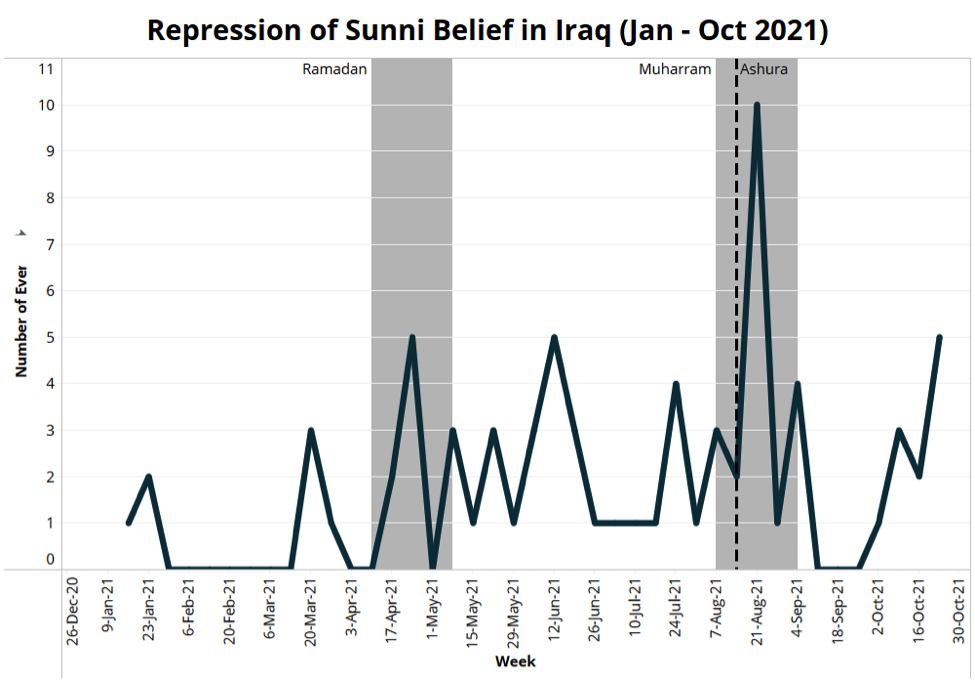

Meanwhile, there was also increased targeting of Sunni citizens across this period. During Muharram, ACLED-Religion records 11 judicial harassment events targeting Sunni citizens for sectarian reasons, signaling the highest peak of this type of repression in 2021 (see figure below). Notably, around 36% of these ‘judicial harassment’ events were concentrated in Al Kadhmiyah, a Shiite stronghold in Baghdad where sectarian divisions are widely apparent (Los Angeles Times, 5 July 2014). While this coincides with Ashura season, it is unclear whether it can be directly correlated with the occurrence of the Shiite festival. Since 2003, Sunni Muslims have been the target of security campaigns and systematic discrimination perpetrated by the mostly Shiite Iraqi federal government (USCIRF, 2021).

Yemen

Since 2014, Ashura celebrations have gained a new significance in Houthi-controlled Yemen. In contrast to the Twelver Shiite practices marking Husayn’s martyrdom, Zaydi believers have historically commemorated Ashura by fasting on the tenth of Muharram (Salmoni et al., 2010).6In Yemen, Zaydis constitute around 35% of the population and are mostly concentrated in Houthi-controlled areas (United States Department of State, 12 May 2021). Despite being an offshoot of Shiite Islam, the Zaydiyya only marginally differs from Sunni Islam in terms of doctrine and ritual practice (Shuja Al-Deen, 7 June 2021). Starting in the 1980s and increasingly throughout the 1990s, Zaydi revivalists reenergized the celebration of a few select Shiite rituals — and in particular of Yawm Al Ghadir7Yawm Al Ghadir is the day on which Shiite Muslims believe the Prophet Muhammad declared his cousin Ali as his successor (Veccia Vaglieri, 2012). — to counter the spread of Wahhabism and mark their religious identity (Weir, 1997; Weir, 2007). However, after 2011, the Houthi advance in northern Yemen took this revivalism to a new frontier, also encouraging the commemoration of Husayn’s martyrdom.

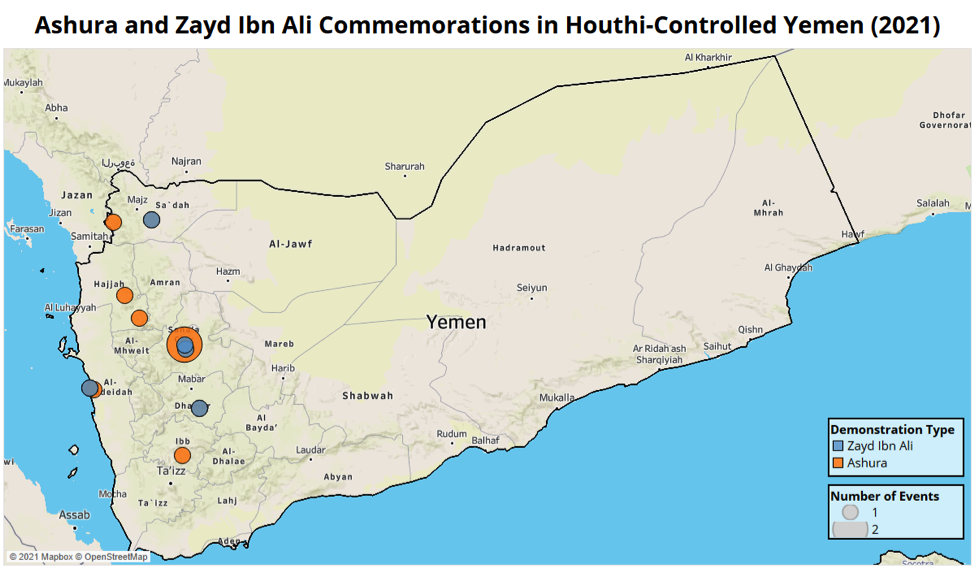

ACLED-Religion records 10 state-sanctioned Ashura demonstrations across six Houthi-controlled governorates, including the Sunni-majority Ibb and Hodeida provinces (see map below). Notably, Ashura mass demonstrations were organized by the regime in spite of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Houthi authorities deny the existence of COVID-19 cases in areas under their control and, accordingly, have avoided decreeing and imposing restrictions on the population (ACAPS, 4 May 2020).

As a means of comparison, ACLED-Religion records just five state-sanctioned demonstrations to commemorate the martyrdom of the founder of the Zaydi school — Zayd Ibn Ali — on 2 September (see map above). This highlights how Ashura, a relatively new celebration for Zaydi Shiites in Yemen, has attained heightened political importance when compared to traditional Yemeni festivals.

The Houthis popularized Ashura in 2013, when — for the first time in Yemen — they commemorated the martyrdom of Husayn with mass demonstrations held in the capital Sanaa and other governorates (Al Wefaq Press, 14 November 2013). Since the Houthi-Saleh alliance took over Yemen’s capital in 2014, Ashura commemorations are increasingly used by the regime as a political tool to showcase consensus, criticize the Saudi-led military intervention in Yemen, and signal the Houthis’ affiliation with the regional Shiite milieu, and in particular with the Iranian regime and the members of the ‘Axis of Resistance’ (Thagafa Qurania, 19 August 2021; Al Monitor, 14 April 2020).

ACLED-Religion only captures one ‘non-violent harassment’ event associated with Ashura, marking an attempt by the Houthi regime to impose on educational institutions the commemoration of Ashura, the martyrdom of Zayd Ibn Ali, and the hijra (migration) of the Prophet Muhammad during Muharram. This level of religious repression is negligible when compared to what is observed during other religious festivals. For instance, in the lead up to the Mawlid Nabawi, the Prophet Muhammad’s birthday, Houthi authorities exacted religious taxes and forced the general population to commemorate the event in a systematic way that reached into nearly every area under their control (for more, see this ACLED-Religion Weekly Overview). The imposition of these policies was made easier by the fact that the Mawlid Nabawi is widely accepted across both Sunni and Zaydi communities. On the contrary, the imposition of Ashura — a Shiite festival — would arguably trigger a reaction in part of the population, especially in Sunni-majority provinces.

Bahrain

Bahrain is the only Gulf country where Ashura is a national holiday and commemorations are allowed to take place publicly (USCIRF, April 2020). Nonetheless, the politico-religious divide between the Sunni Muslim Al Khalifa royal family and the majority Shiite population — estimated to account for 60% to 70% of Bahrain’s Muslim population (BICI, 10 December 2011) — remains a major driver of religious repression. In Bahrain, Ashura celebrations are rooted at the community level and bear religious, social, and political meanings. In the lead up to Ashura, neighborhoods are adorned with black banners to display sorrow over Imam Husayn’s death and the matams or hussayniyyas (Shiite congregation halls) organize public chest-beating processions (mawkabs). However, what lies at the core of the dispute between Sunni regime and Shiite citizens is Ashura’s political potential. In Bahrain’s history, Ashura had been used as the launching pad for social uprisings in the 1950s and 1990s (Fibiger, 2010).

In 2020, the Al Khalifa regime introduced severe limitations to Ashura-related celebrations under the pretext of curbing the spread of COVID-19. These restrictions triggered a crackdown targeting matams, as well as Shiite civilians and religious leaders (ADHRB, 5 October 2020). The prominent Shiite cleric Ayatollah Sheikh Isa Qassim interpreted the restrictions as targeting the Shiite community for “political reasons” (IQNA, 15 August 2020). He condemned the regime’s apparent double-standards around the enforcement of COVID-19 restrictions, as other activities and facilities — such as pools and sport clubs — remained open (Bahrain Mirror, 19 August 2021).

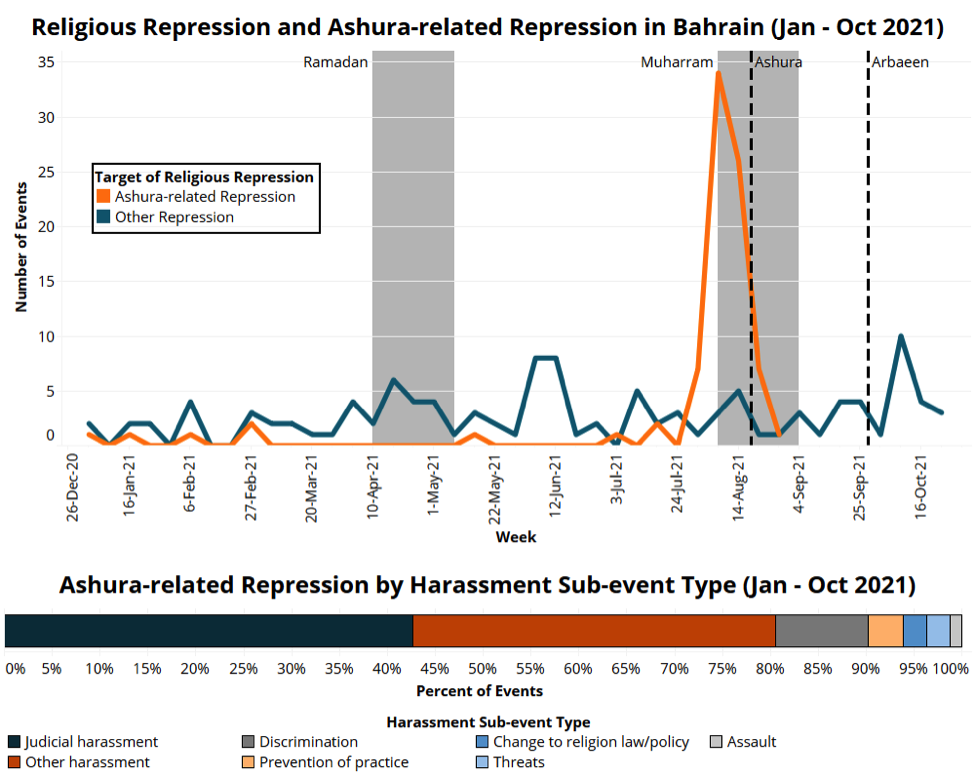

In 2021, ACLED-Religion captures 84 repression events targeting Ashura-related rituals in Bahrain — around 42% of all repression events recorded in the country between January and October 2021. Ashura-related repression spiked around the beginning of Muharram, and trended sharply down after Ashura commemoration on 18 August (see graph below). However, Ashura-related repression events are also recorded in earlier months of 2021, indicative of continued repression of Shiite civilians and religious leaders due to their involvement in 2020 Ashura rituals.

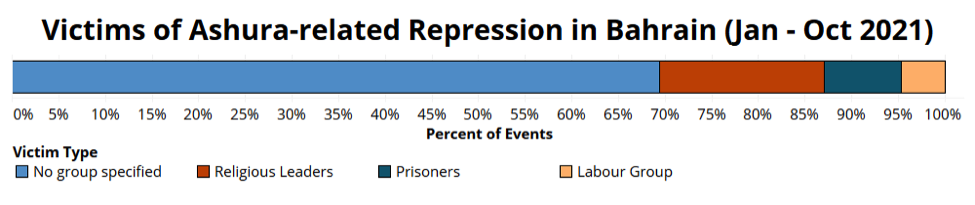

In August 2021, Bahraini authorities validated a legal framework that introduced several religious practice restrictions aimed at curbing the spread of COVID-19. In doing so, the framework had the effect of repressing Ashura practice and expression. Provisions within the framework limited the display of Ashura banners, limited attendance at houses of worship to 30 vaccinated adult individuals, and banned children from attending Ashura rituals. ACLED-Religion records these restrictions being enforced by means of ‘judicial harassment’ (35 events) and the removal of Ashura banners (31 events coded as ‘other harassment’). As in previous years (USCIRF, April 2020), Ashura-related repression especially targeted religious leaders and prisoners. Bahraini authorities arrested and summoned preachers, religious singers (raddud), and matams directors for taking part in Ashura commemorations. Shiite prisoners were denied the right to celebrate Ashura and punished if they performed rituals, including with discriminatory acts like being prevented from contacting their families. ACLED-Religion data show that these two categories — religious leaders and prisoners — account for around 26% of repression victims in Bahrain (see figure below).

Conclusion

In 2021, three countries covered by ACLED-Religion — Iraq, Yemen, and Bahrain — account for nearly all Ashura-related events, with the majority of repression events concentrated in Bahrain. The three countries examined here differed as to the configuration of political and religious environments, yielding different patterns of repression.

In Iraq, Ashura season is widely marked by the majority Shiite population, with massive commemorations taking place in spite of the COVID-19 pandemic. While the government and religious authorities warned the population against COVID-19 health risks and introduced considerable restrictions surrounding Ashura, these measures were not enforced. In spite of security measures introduced nationwide to protect the Arbaeen pilgrimage, a few Arbaeen pilgrims were accidentally targeted during tribal clashes, reflecting the overall precarious security situation in Iraq. A spike in the sectarian repression of the Sunni population was also recorded during Ashura season.

In Houthi-controlled Yemen, state authorities organized Ashura demonstrations as a means to express political grievances and signal proximity to the global Shiite milieu. These mass demonstrations were organized by Houthi authorities regardless of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. State-sanctioned Ashura celebrations are new to the country, as historically Zaydi believers would not commemorate the martyrdom of Imam Husayn.

Lastly, in Bahrain, the politico-religious divide between the Sunni regime and majority Shiite population appeared to be a major driver of repression. Ashura commemorations are deeply rooted at the community level and state authorities actively suppressed Ashura-related rituals by issuing COVID-19 restrictions and targeting the population via judicial harassment, singling out religious leaders and prisoners for particularly high levels of repression.

Across all countries examined, the meaning of Ashura transcends religion and speaks to the broader political context. Ashura processions can be used by regimes to express political grievances and build consensus, as is the case in Yemen. Contrastingly, the state can consider Ashura as a political threat and suppress mourning rituals, as exemplified by the Bahraini case. Regimes endorsing Shiite Islam might be less likely to repress Ashura rituals and more inclined to impose security measures on the general population to facilitate the celebrations, as observed in Iraq. Heightened identity salience can also lead to increased repression of non-Shiite religious minorities, as also occurred in Iraq. In all countries examined, legal provisions — such as COVID-19 restrictions — are strategically manipulated by the state in coincidence with Ashura to pursue political goals.

Funding for this report was provided by the US Department of State’s Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations through the Quantifying Religious Repression and Religious Conflict grant. The views expressed in this report are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the United States Government.

© 2021 Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). All rights reserved