On 9 December 2021, Indian farmers announced an end to demonstrations against the country’s aborted agricultural reforms (The New York Times, 9 December 2021). Still, key organizers maintain that the movement will continue to monitor government implementation of demonstrator demands into 2022 (The Free Press Journal, 12 December 2021). The decision followed the repeal of agricultural laws deregulating the sale, pricing, and storage of farm produce on 29 November (Reuters, 29 November 2021), more than a year after they were enacted on 20 September 2020 (BBC News, 16 February 2021). As of 9 December 2021, ACLED records over 5,200 demonstration events associated with the farm laws across India.

Farmers had been demonstrating against three laws: the Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, the Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Act, and the Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act (The Indian Express, 21 November 2021). Together, the farm laws would change the rules around the sale and pricing of farm produce, allowing private buyers to purchase directly from farmers outside the assured minimum price system (BBC News, 27 September 2021). Many agricultural workers have been concerned about potential vulnerabilities in free-market conditions and an erosion of state subsidies (BBC News, 27 September 2021). In particular, demonstrators voiced concern for the future of the Minimum Support Price (MSP), a fixed pricing guarantee for certain crops that insures farmers against price volatility (The Caravan, 19 September 2020).

The potential impact of these laws on farmers’ livelihoods initially sparked demonstrations in northern states, the ‘bread basin’ of India, when the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi first introduced its reform policy in June 2020 (CNN, 6 March 2021). The most prominent organizer of the demonstrations, the Samyukt Kisan Morcha (SKM), has acted as a key umbrella organization for about 40 national and regional farmer unions, along with the Bharatiya Kisan Union (BKU) (The Indian Express, 30 January 2021). In November 2020, when the SKM organized nationwide demonstrations, tens of thousands of demonstrators set up camps on highways leading to New Delhi (Al Jazeera, 22 July 2021; Indian Express, 25 November 2020). As the farmer movement expanded, it also gained support from labor groups, students, and political parties. Major opposition parties, like the India Trinamool Congress (TMC) and left-wing parties, such as the Communist Party of India (Marxist), also organized and joined demonstrations (Business Standard, 5 December 2020). In addition to individual demonstrations drawing tens of thousands of demonstrators, millions of people joined strikes in solidarity with demonstrating farmers (Reuters, 19 November 2021; CNN, 6 March 2021).

With an expanding support base, the farmer movement also encapsulated protests against other social and economic challenges such as land acquisition projects, inflation, and crop damage (The Wire, 5 December 2020; Hindustan Times, 16 September 2021; Indian Express, 9 July 2021). As such, the persistence and widespread appeal of farmer demonstrations posed a challenge to the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) electoral base. The repeal of the farm laws comes ahead of elections in northern agricultural states, including Uttar Pradesh and Punjab, beginning in February 2022 (Deutsche Welle, 22 November 2021).

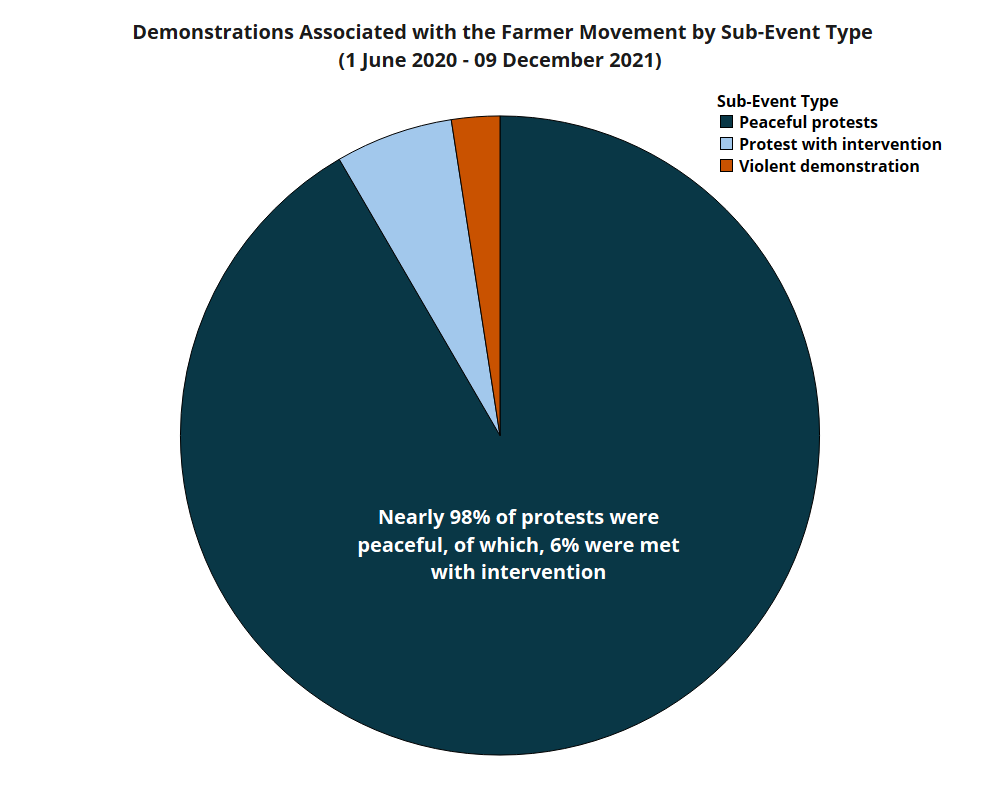

This report explores the growth, features, and longevity of the farmer movement in India, analyzing changes in demonstration activity and demonstrator interactions with state authorities. Despite high-profile incidents of violence and early attempts by the ruling BJP to characterize the entire farmer movement as violent (India Today, 22 July 2021; DNA, 27 January 2021), analysis of the data reveals that the demonstrations have been largely peaceful. ACLED data show that since the beginning of the farmer movement in June 2020, nearly 98% of all demonstration events related to the farmer movement have been non-violent. By examining farmer responses to violent incidents and government restrictions, the report highlights the strategies that have contributed to the movement’s nationwide appeal and momentum. Despite several prominent clashes between police and farmers, demonstration organizers have focused on de-escalating conflicts and mobilizing farmers in a peaceful way to sustain the movement. The coordination between farmer union organizers and demonstrating farmers has contributed to the resilience of the movement on a nationwide level.

Farmer Movement Trends

From Regional Focus to Sustained Nationwide Presence

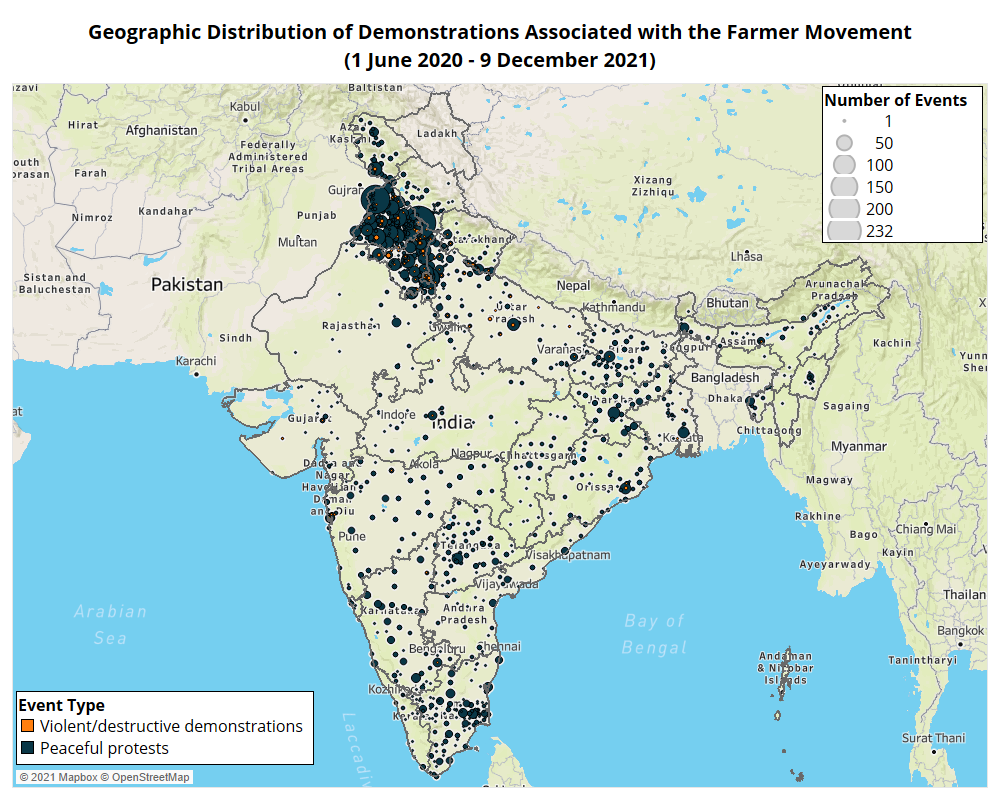

While the farmer movement has had nationwide reach, its presence has been most prominent in north India. ACLED records the highest number of farmer movement-related demonstration events in Punjab state, where demonstrations began in June 2020, followed by Haryana state and the National Capital Territory of Delhi (see map below).

Following several months of demonstrations centered in north India, the farmer movement expanded nationally after parliament enacted the farm laws on 20 September 2020. This national expansion was supported by a call for demonstrations from several farmer unions on 25 September (The Indian Express, 16 September 2021). In late November 2020, farmers also set up camps outside New Delhi (Tribune India, 27 November 2020). These camps drew farmers from multiple states — such as Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Gujarat – and became the focal points sustaining the movement for over a year (The Guardian, 12 February 2021).

ACLED also records significant numbers of demonstration events in Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh, and Maharashtra. Rice farmers from these states are primarily reliant on MSP procurement and demonstrators have expressed concerns that the farm laws would undermine their bargaining power (Hindustan Times, 19 November 2020). Part of the reason for the discontent also likely stemmed from the quick passage of the reforms without referral to a parliamentary panel or consultations (Foreign Policy, 10 December 2020).

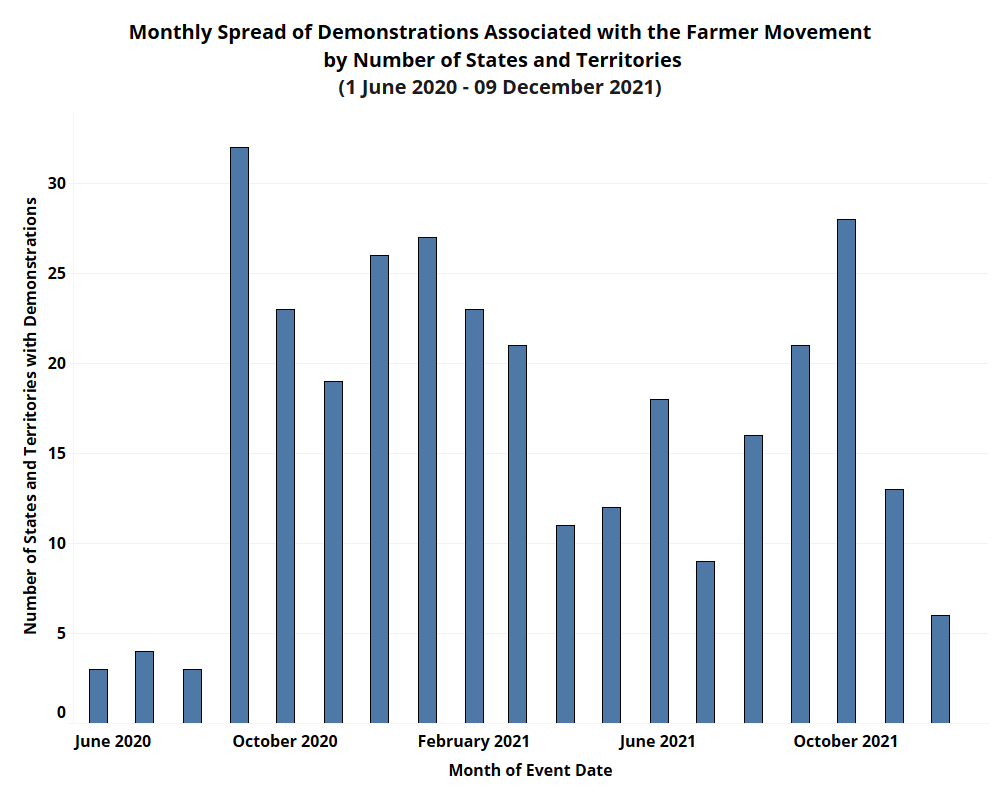

After the nationwide expansion of the farmer movement in September 2020, the movement maintained a presence across the country for more than a year. Between September 2020 and November 2021 — the final complete month of demonstration activity — demonstrations were reported in at least nine states and territories each month (see graph below), with a monthly average of 19 distinct states and territories.

Largely Peaceful Despite Periodic Outbreaks of Violence

Violent manifestations of tensions between Indian authorities and farmers have often stood out as a focus of media attention around the farmer movement. Tensions first escalated considerably in November 2020 when police prevented demonstrations in New Delhi (Al Jazeera, 27 November 2020). On 26 November 2020, thousands of farmers clashed with police, who used tear gas and water cannons to stop them from removing barricades to enter the capital (BBC News, 27 November 2020). Since then, two specific outbreaks of violence have featured prominently in media reports on the movement. On 26 January 2021, India’s Republic Day, riots broke out across New Delhi during a tractor march as tens of thousands of demonstrators clashed with police forces and one farmer died (BBC News, 26 January 2021). More recently, on 3 October 2021, a convoy of cars linked to a federal minister’s son allegedly ran over farmers demonstrating against farm laws in Uttar Pradesh state, killing four farmers.

These incidents occurred amid Indian government attempts to suppress farmer dissent and call into question the movement’s commitment to peaceful protest. The government response translated into arrests of demonstrators and the prosecution of sedition cases against journalists (Al Jazeera, 1 February 2021; BBC News, 27 January 2021). Furthermore, the government temporarily suspended internet services after the Republic Day and 3 October incidents (India Today, 8 October 2021). Meanwhile, some BJP leaders have also referred to the farmers as “anti-nationals’’ in an attempt to portray their movement as disruptive (AP, 27 January 2021). BJP figures dismissed Sikh farmers’ concerns as being driven by religious nationalism, labeling them “Khalistanis,” in reference to the separatist movement that seeks an independent Sikh homeland — “Khalistan” — in north India (AP News, 27 January 2021). Moreover, despite a more conciliatory tone when recently announcing plans to repeal the farm laws (The Guardian, 20 November 2021), Modi had also previously accused the farmer movement of harboring agitators stirring up tension (The Guardian, 12 February 2021).

Contrastingly, some Indian media and activists have referred to the demonstrations as acts of “satyagraha,” inspired by Mahatma Gandhi’s commitment to non-violent civil disobedience (The Conversation, 17 February 2021). Data-driven analysis makes it clear that despite some high-profile incidents of violence, alongside the government’s negative characterization of the movement, the farmer demonstrations have been largely peaceful.

Since the beginning of the movement in June 2020, ACLED data show that the vast majority of farmer demonstration events have been non-violent. As of 9 December 2021, ACLED records more than 5,000 peaceful protests, representing almost 98% of all demonstrations (see figure below). While police physically intervened to stop peaceful protesters in about 6% of all events, demonstrators only engaged in violence in about 2% of demonstrations.

Demonstrator Responses to Violence

In addition to the movement’s predominantly peaceful mobilization on a national scale, demonstrators have also shown an ability to respond to violence with strategies to mitigate further conflict and government repression. Responses to two prominent violent incidents, the Republic Day clashes at the Red Fort on 26 January 2021 and a deadly car-ramming incident on 3 October 2021, illustrate how farmer organizers acted to de-escalate major tensions while maintaining mobilization. While these events attracted widespread media coverage (CNN, 27 January 2021; The New York Times, 4 October 2021), insufficient attention has been paid to ensuing peaceful farmer demonstrations, which have been pivotal in sustaining the profile and momentum of the movement.

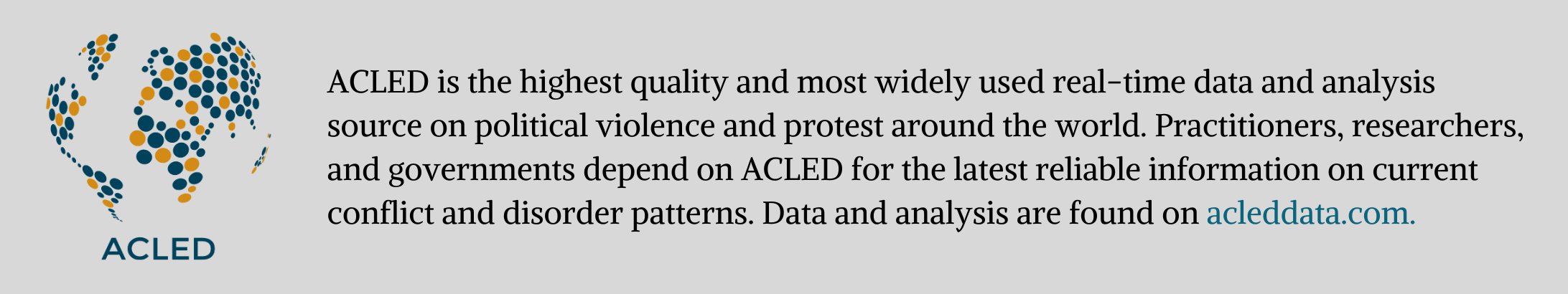

Republic Day 2021 Violence and the Redirection of Nationwide Demonstrations

On 26 January 2021, a tractor rally against the agriculture reforms turned violent after a group of farmers pushed into New Delhi’s Red Fort complex and clashed with authorities. Police had authorized the rally in areas where it would not interfere with the Republic Day parade in central Delhi (BBC News, 26 January 2021). Although many farmers followed the police-authorized routes on the outskirts of the city, other demonstrators pushed through police barricades and clashes broke out (The Guardian, 26 January 2021). Both demonstrators and police were reportedly injured in the clashes, and one farmer died when his tractor overturned.

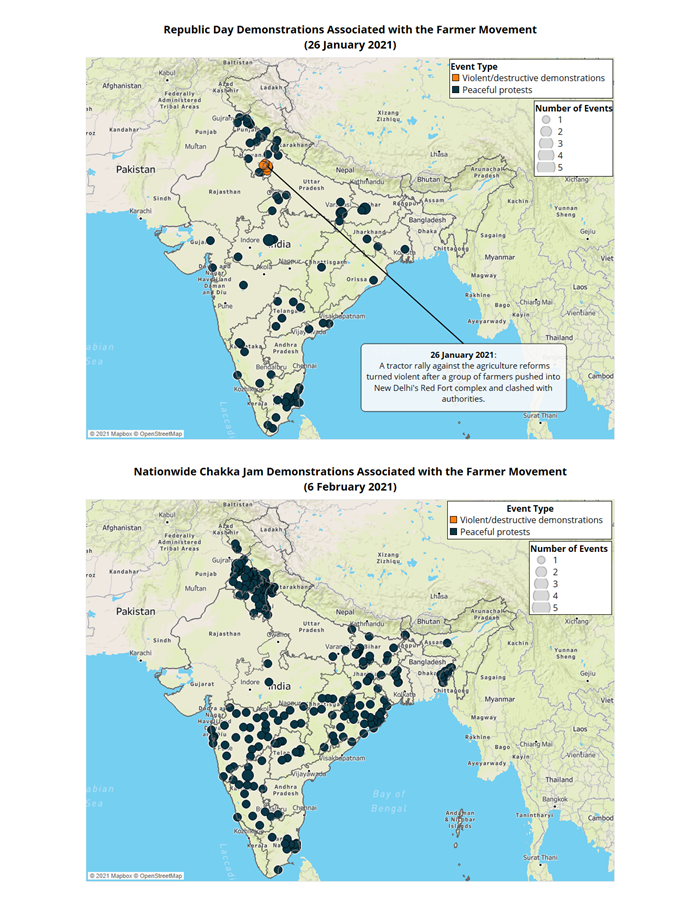

In the days following Republic Day, the SKM and BKU called for a nationwide ‘chakka jam’ (road blockade) to be held on 6 February in response to the government-initiated shutdown of internet services at protest sites and suspension of Twitter accounts of farmer activists (Hindustan Times, 4 February 2021; The Wire, 5 February 2021). However, with tensions still high over the recent violence, the farmer unions decided to organize ‘dharnas’ (peaceful protests) in Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, and the New Delhi region, instead of road blockades to “to avoid any untoward incidents” (The Tribune, 5 February 2021). SKM and BKU leaders also publicly asked farmers to demonstrate peacefully (The Tribune, 5 February 2021).

On 6 February 2021, farmer road blockades proceeded largely outside key flashpoints in Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand amid an increased deployment of security forces (Mint, 7 February 2021). Apart from denouncing the new laws, farmers also voiced concerns about the recent internet shutdown as well as arrests and alleged harassment of journalists (The Wire, 5 February 2021). Local farmer groups followed organizers’ calls to avoid demonstrations near recent sites of violence and remain peaceful (The Guardian, 6 February 2021). These demonstrations substantially increased in scale by over 250% compared to demonstrations on 26 January. Notably, the demonstrations on 6 February were entirely peaceful. Despite heightened tension between police and demonstrators, farmers did not engage in clashes, with ACLED recording more than 200 peaceful protest events associated with the farmer movement (see maps below).

October 2021 Car Ramming and a Surge in Mostly Peaceful Demonstrations

October 2021 Car Ramming and a Surge in Mostly Peaceful Demonstrations

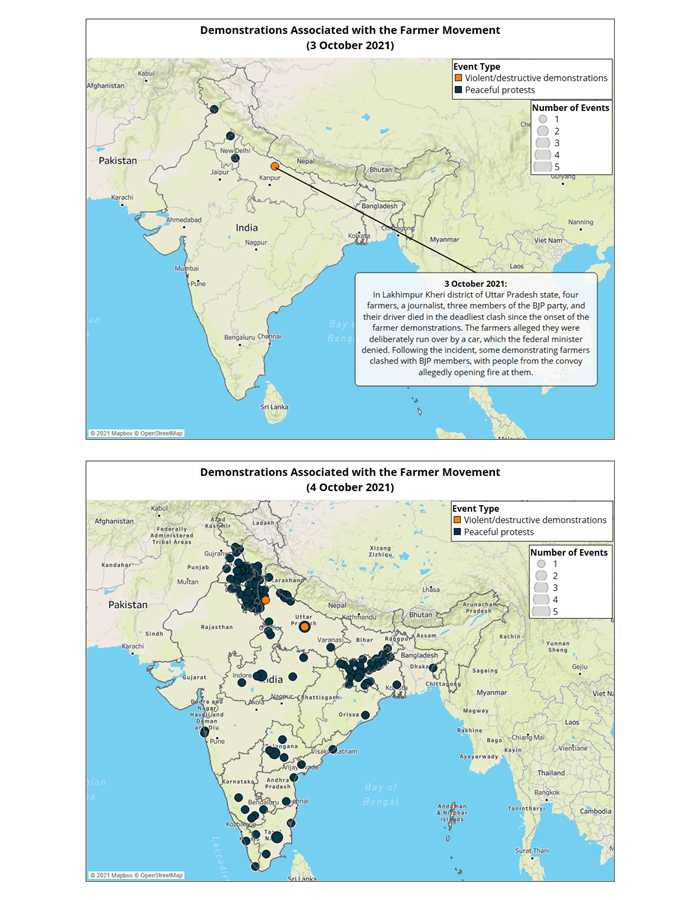

Around eight months later, the response strategy of the farmer movement was tested again following another violent incident. On 3 October 2021, nine people were killed after violence erupted during a demonstration against the farm laws in the Lakhimpur Kheri district of Uttar Pradesh. Clashes broke out after a convoy of cars, linked to a federal minister’s son, allegedly ran over a group of demonstrating farmers expecting a visit from two ministers (The Guardian, 4 October 2021). Four farmers, a journalist, three members of the BJP party, and their driver died in the deadliest clash since the onset of the farmer demonstrations. The farmers alleged they were deliberately run over by a car, which the federal minister denied (The Hindu, 4 October 2021). Following the incident, some demonstrating farmers clashed with BJP members, with people from the convoy allegedly opening fire.

In response to the incident, farmers vowed to step up their protests and demanded action against the minister and his son (Al Jazeera, 4 October 2021). The SKM called on farmers across the country to protest peacefully in front of district judicial and commission offices on 4 October (Hindustan Times, 4 October 2021). This call for demonstrations led to the highest single-day total of farmer movement-related demonstration events since the one-year anniversary of the demonstrations in September 2021, with more than 100 demonstrations. Farmers again used their ability to organize quickly following a violent event and coordinate a large-scale peaceful response. In line with demonstration decisions following the outbreak of violence on Republic Day, ACLED did not record any demonstrations in the Lakhimpur Kheri district, where the car ramming took place. All but two demonstrations remained non-violent (see maps below), including those in Uttar Pradesh, as farmers followed the SKM’s guidance.

Conclusion

On 9 December 2021, farmer unions and thousands of farmers camped around New Delhi finally called off demonstrations, having outlasted the farm laws and having drawn further concessions from the state. Security agencies agreed to drop criminal charges against farmers and a new committee was formed to consider further price guarantees (The Washington Post, 9 December 2021).

Over a year since the passing of the three farm laws, the farmer movement had sustained its strength and appeal. The initial passage of the farm bills in September 2020 galvanized farmers opposing the changes into quickly mobilizing across the country. Demonstrations spread from the northern states of Punjab and Haryana to other agriculture-dependent states in south and central India. Since the laws were enacted, despite a few high-profile violent events, the demonstrations sustained their predominantly peaceful nature. As state forces focused on restricting demonstrators, with some voices from the government seeking to discredit the movement, farmers drew on their own strategy. In response to the violent incidents in January and October 2021, farmer unions maintained the movement’s momentum by promptly mobilizing farmers after violent standoffs. They also shifted demonstrations away from conflict hotspots to avoid further clashes. This approach aimed at avoiding conflict escalation, including appeals to protest peacefully, were largely followed by demonstrators.

In addition to mobilizing on a national scale in a predominantly peaceful way, the farmer movement has also demonstrated the capacity to respond to violence with strategies to mitigate further conflict and government repression. Together, these trends distinguished the movement across more than a year of activity.

© 2021 Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). All rights reserved.

October 2021 Car Ramming and a Surge in Mostly Peaceful Demonstrations

October 2021 Car Ramming and a Surge in Mostly Peaceful Demonstrations