Election Watch

Kenya’s Political Violence Landscape in the Lead-Up to the 2022 Elections

9 August 2022

Kenya went to the polls on 9 August 2022 after a five-year cycle, marking the third general election since the promulgation of a new constitution in 2010. This represents the end of the second and final term of the Jubilee Alliance party government under President Uhuru Kenyatta and Deputy President William Ruto, a current presidential contender. The presidential campaign between Raila Odinga — another ‘legacy’ candidate who has previously run four unsuccessful presidential campaigns — and Ruto has experienced some local troubles, but the focus during this campaign is whether the Kenyan electoral landscape has really shifted to emphasize class, demographic, and elite divisions.

A large number of positions are up for a vote in the elections. The Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) is mandated to conduct the general election for 22,120,458 registered voters (The Kenya Gazette, 21 June 2022), and it includes voting for president and deputy president; 47 governors and their deputies; 47 members of the senate; 47 women representatives; 290 members of parliament; and 1,450 members of the County Assembly across a total of 46,229 polling stations (Daily Nation, 6 August 2022). With campaigns having officially ended on the evening of 6 August, the contest is a two-horse race between Odinga’s Azimio la Umoja One Kenya Coalition Party and Ruto’s Kenya Kwanza Alliance.

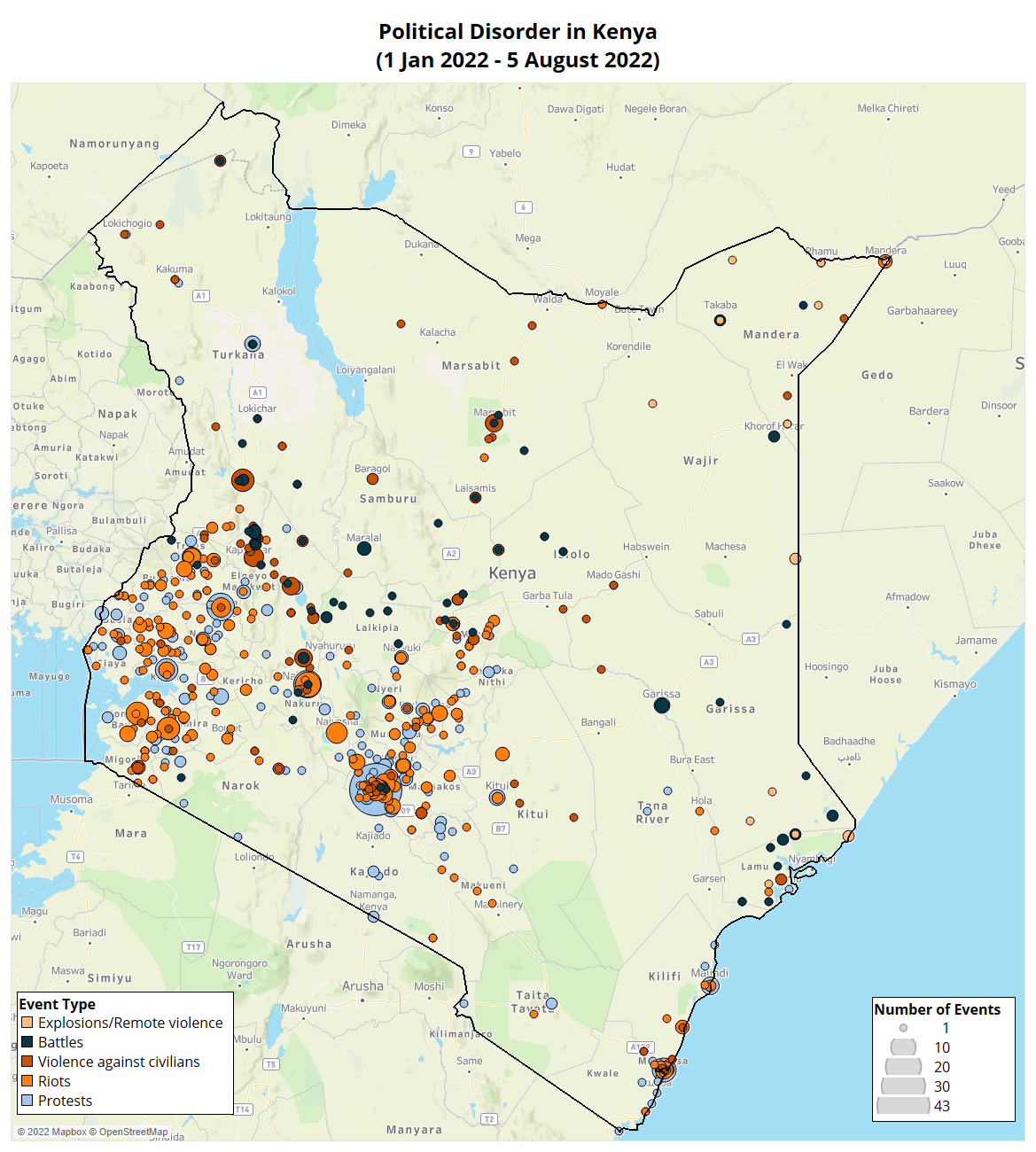

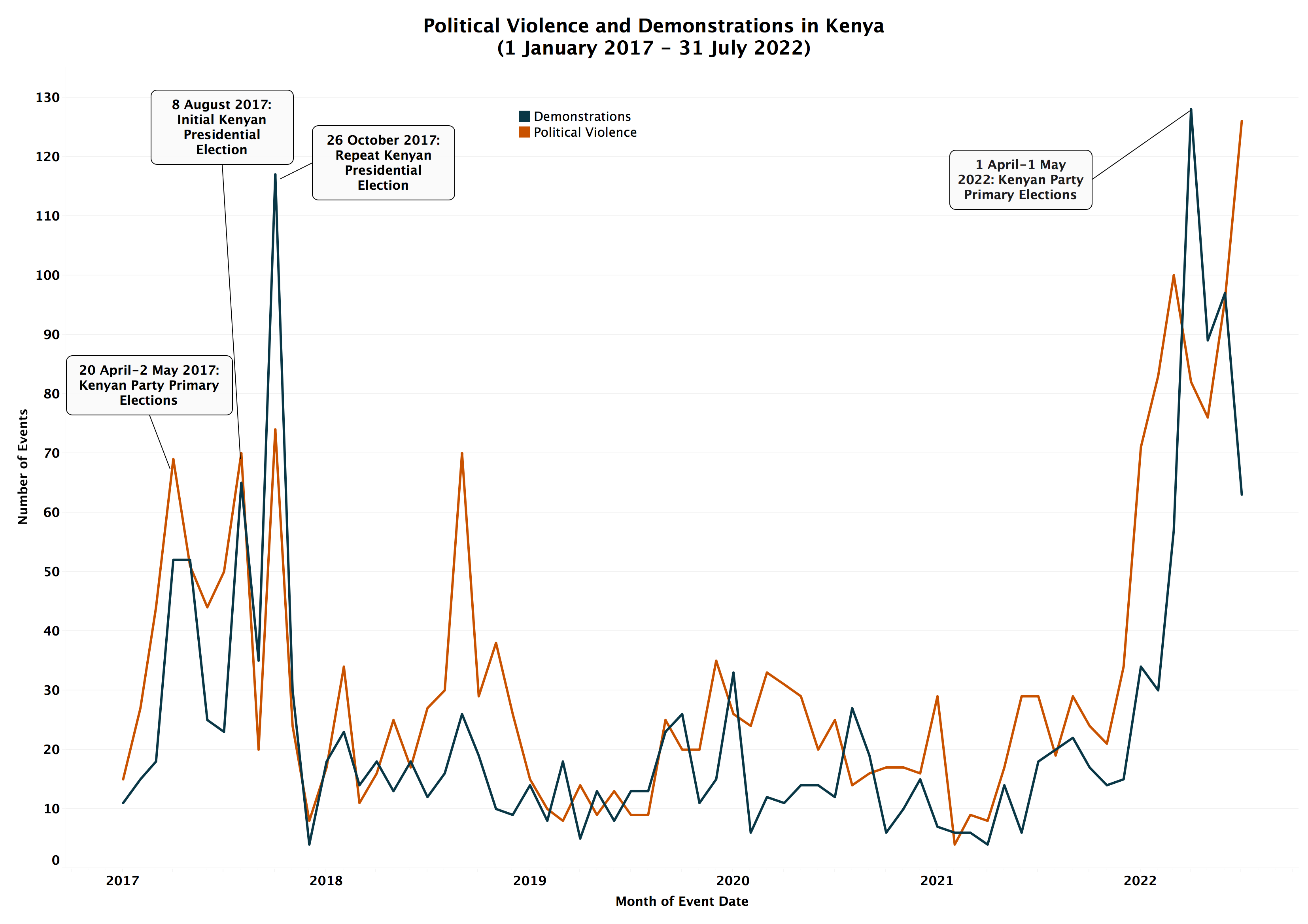

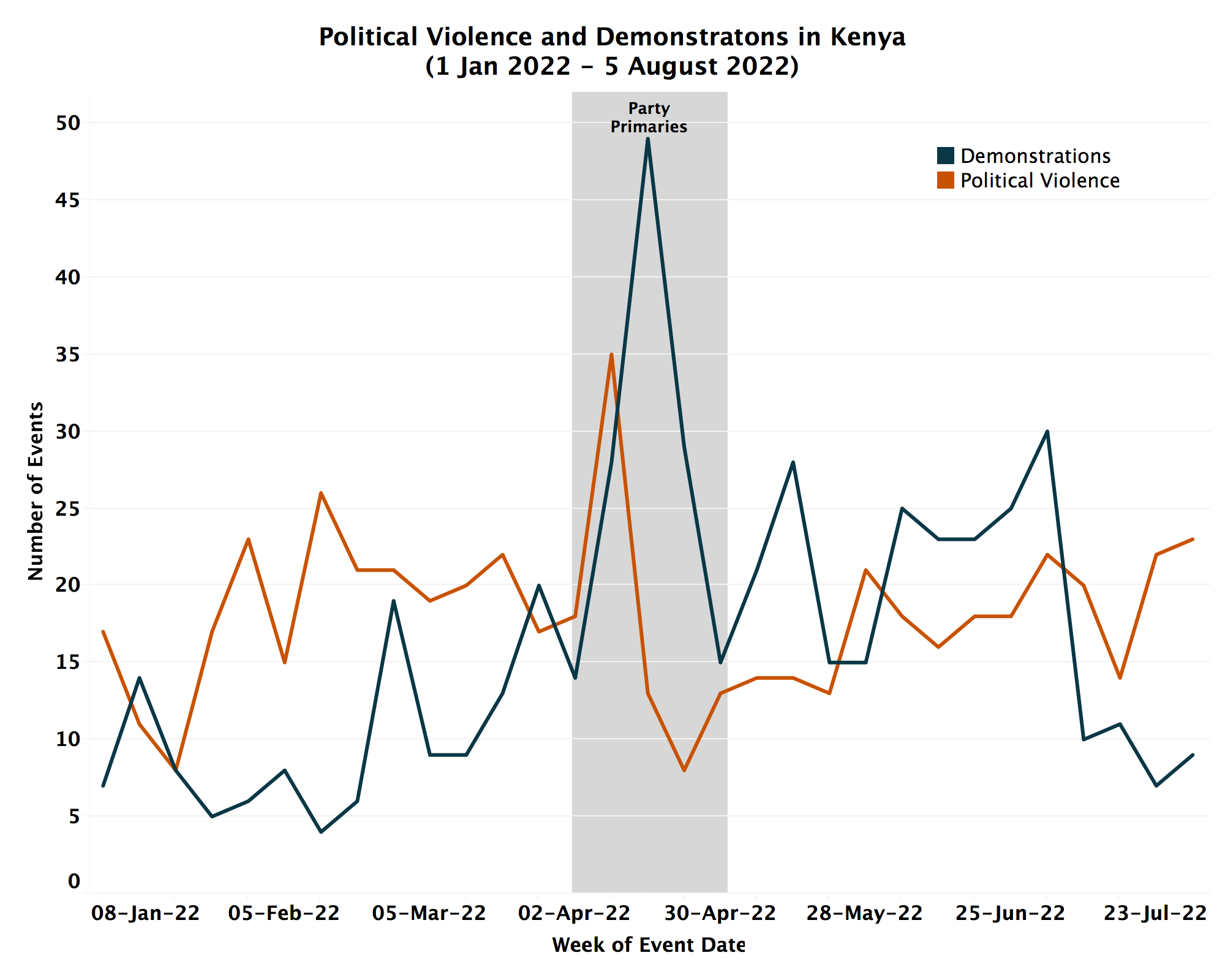

Political disorder1This is a term referring collectively to all ACLED event types, including Battles, Explosions/remote violence, Violence against civilians, Protests, and Riots, with the exception of Strategic developments. For more on Strategic developments and how to use them, see this primer. in Kenya often increases during election periods. ACLED has recorded peaks in both political violence and demonstration events during previous election years, including most recently in 2017. So far in 2022, more than 1,060 political disorder events have been reported as of 5 August — already the largest number of incidents recorded for any year since the start of ACLED coverage of Kenya in 1997.

Of this total, over 400 events are peaceful protests, including recent protests against the increased cost of living that have been held across many major towns. Nearly 400 riot events have also been documented since the beginning of the year, with a reported spike in violent demonstrations and mob violence during the party primaries (see graph below). Reported rioting and protest activity in the lead-up to the 2022 elections has far exceeded the level of activity reported ahead of the 2017 elections, when nearly 110 peaceful protest events and 160 riot events were recorded.

Amid elevated levels of protest and riot activity, armed clashes between Kenya’s security forces and Al Shabaab militants — ongoing since Kenya’s incursion into Somalia in October 2011, under Operation Linda Nchi (Protect the Nation) (Ekanem, 2022) — have also been at heightened levels in 2022. The most hard-hit areas are coastal Lamu county and the former North Eastern Kenya region.

Violence against civilians has been highest in the Kerio Valley region, where women and children have been particularly affected (People Daily, 23 February 2022). So far in 2022, civilian targeting has resulted in at least 25 reported fatalities in Baringo, 23 in Elgeyo, and four in West Pokot, all related to pastoral militia attacks. At least 20 further fatalities were reported in the neighboring county of Turkana.

During the recent presidential debate on 26 July, Ruto attributed the violence to politics meant to punish his supporters (Daily Nation, 27 July 2022). This allegation was dismissed by Interior Minister Fred Matiang’i (Citizen Digital, 27 July 2022).

The re-emergence of outlawed groups such as the Mombasa Republican Council (Daily Nation, 30 June 2022) and the emergence of gangs such as ‘Confirm’ in Nakuru (Kenya Standard, 28 June 2022) and its subsidiary ‘Nyuki’ (Citizen Digital, 15 July 2022); ‘Miticharaka’ in Tana River (The Star, 21 July 2021); and ‘Bogi Mawe’ in Kitale (Daily Nation, 26 July 2022), among others, has also contributed to increased violence, including murder and muggings. Citing the Coastal region, Interior Minister Matiang’i recently acknowledged that criminal gangs are grouping ahead of the general election (Kenya Standard, 20 July 2022). In Nakuru, for instance, police have probed three members of parliament over their alleged links to the gangs (Daily Nation, 28 June 2022). Overall, there is little evidence of concerted political violence by a specific party in the pre-election period, but many active gangs are available to be repurposed to this end if parties deem it necessary.

What election outcomes may lead to violence? While acknowledging that the election is hotly contested at all levels, special attention must be paid to the presidential vote. In this context, there are at least two possible scenarios. The first scenario is an unclear outcome. In this case, none of the leading candidates secures the mandatory 50% plus one vote and at least a quarter of the votes in 24 of the 47 counties, leading to a runoff. This portends that the current political violence landscape will persist or even intensify as the country prepares for the runoff. However, the chances of this scenario are slim, given that some of the latest polls have already projected Odinga to garner as much as 53% of the vote (People Daily, 3 August 2022).

The second scenario involves a clear election outcome, after which there could be winner-violence and/or — more likely — loser-violence. The IEBC has a seven-day window to announce the winner of the results. It is alleged that both camps are gathering potential evidence to dispute an unfavorable outcome in the supreme court (Daily Nation, 31 July 2022). The potential for violence could be high during this period as tensions rise over disputed results (for more, see the presidential petition timelines, as recently published here). Notably, ACLED records a secondary spike in political disorder coinciding with the re-run of the 2017 elections in October following the Supreme Court’s decision to annul the August results (see graph above). Violence along ethnic lines is also possible in the strongholds of the leading presidential candidates. Accordingly, a report by the National Cohesion and Integration Commission (NCIC) categorizes six counties — Nairobi, Nakuru, Kericho, Kisumu, Uasin Gishu, and Mombasa – as high risk areas for such violence (NCIC, 2022), including both Odinga and Ruto strongholds. Already police officers have arrested and charged nine students for allegedly circulating leaflets warning certain communities against voting in a certain manner (The Star, 5 August 2022).

In this context, the government has attempted to assure the public of its commitment to a peaceful election and the security of all Kenyans. Already there is a heavy deployment of more than 150,000 security officers drawn mainly from the National Police Service and backed up by their counterparts from the Kenya Prisons Service, the National Youth Service, the Kenya Forest Service, and the Critical Infrastructure Unit (Daily Nation, 3 August 2022). In the Rift Valley specifically, the security agencies have established a multi-agency command center meant to coordinate and respond to any issues that may arise (The Star, 4 August 2022).

Currently, signs point to the second post-election scenario outlined above as the most likely outcome. In this event, Kenya could see incidents of loser-violence in high-risk areas, with localized pockets of protests and clashes with police among those dissatisfied with the result. Still, election day itself remained relatively calm, and the outcome is now awaited with hope the announcement and subsequent change in power will be peaceful.