Guest Contribution

Jihad Takes Root in Northern Benin

23 September 2022

This report by guest contributor Dr. Leif Brottem uses ACLED data and primary information collected by Dr. Brottem and his team during research in northern Benin.

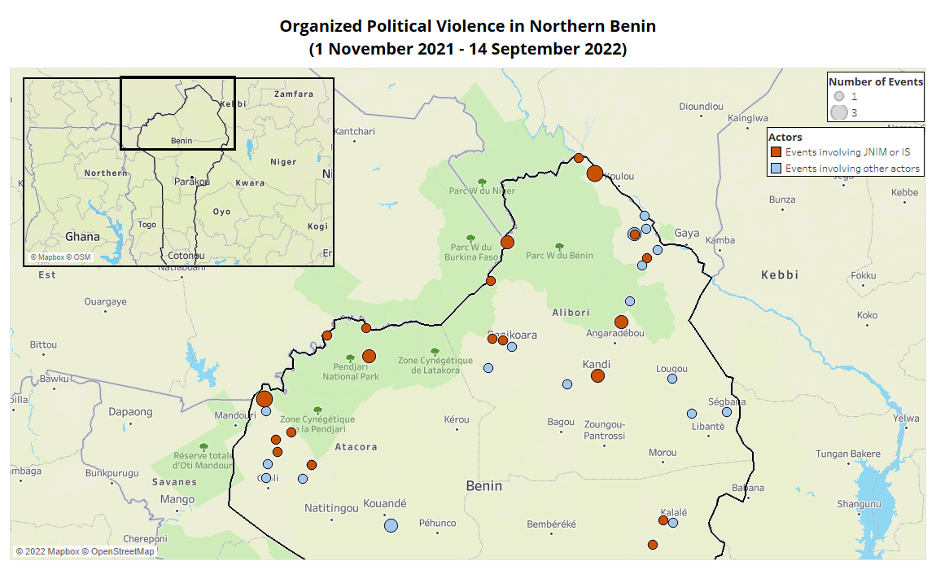

The 14 September 2022 killing of two customs agents days after the kidnapping of three individuals with government ties signals an alarming uptick in jihadist violence in northern Benin (Les 4 Vérités, 14 September 2022). ACLED records 28 organized political violence events in northern Benin attributed to Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) or the Islamic State between 1 November 2021 and 14 September 2022 (see map below). It is increasingly clear that jihadist cells have become deeply established in the country’s northern regions. The Beninese government is currently ramping up its threat response, which looks likely to include a security agreement with Rwanda (Radio France Internationale, 10 September 2022). It is more urgent than ever that the country’s counterinsurgency avoids the tragic mistakes of governments in the Sahel by blunting the deepening roots of the insurgency in rural areas.1ACLED and the Clingendael Institute first analyzed escalations risks in the region in the 2021 joint report Laws of Attraction: Northern Benin and Risk of Violent Extremist Spillover.

Recent events in northern Benin and other theaters of jihadist expansion, including western Mali, suggest that a solution will not be logistical: it is beyond strengthening public administration or improving basic services. Insurgents in northern Benin are taking control during the night, as they have done across the Sahel, by stealthily riding in motorcycle convoys with a single illuminated headlight in order to stage hit-and-run attacks and descend on villages where they cow inhabitants and receive clandestine support from their sympathizers. Locals observe that these unpredictable night moves allow jihadists to be everywhere and nowhere, presenting a challenge to even the most sophisticated security response that Rwandan forces can bring.

Increased Civilian Threat

Jihadist militants also gain footholds in local communities by preaching and infiltrating Quranic schools. In April, a Quranic teacher and eight of his students were kidnapped from a village in Banikoara, a district in northeastern Benin that adjoins W National Park and serves as an important transportation link with southeastern Burkina Faso. According to sources who spoke to the author, the Quranic teacher, who was later executed by the armed insurgents, was thought to have been trying to sever his alleged ties with jihadists based in neighboring Niger. One victim of the 9 September kidnapping, which took place in the border district of Karimama, was also taken to Niger and later released. The lack of details regarding what took place during his captivity and the terms of his return to Karimama adds to the confusion and fear that reigns in local communities there.

Jihadist presence within protected reserves is one of the most acute threats that civilians currently face. As the aforementioned incidents illustrate, these groups target local communities, especially pastoralist ones, in their efforts to further entrench their power and control over these sparsely populated areas. The mix of mobile attacks emanating out of nature reserves, Islamist preaching, and violent coercion that jihadists are deploying in certain communities of northeastern Benin has also been observed in western Mali. This tactic also characterized the campaign by Katiba Macina, a JNIM sub-group, to establish a presence within the Boucle de Baoulé National Park in western Mali (for more on Katiba Macina, see the ACLED report Mali: Any End to the Storm?). The 25,000 square kilometer reserve forms an irresistible conduit between areas near the Mauritanian border, where jihadists are well established, and the capital city, Bamako (Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, 1 July 2021). Jihadist activity around Baoulé National Park is concentrated in the district of Kolokani, which is an easy two-hour motorcycle ride to the Malian capital and the military garrison town of Kati that was attacked on 22 July (New York Times, 22 July 2022).

Although jihadist groups have managed to recruit locally around the Baoulé National Park in Mali, that recruitment has been marked by kidnappings, especially during the early phase of its occupation, which could portend a similar pattern in northern Benin. The sheer size of the W and Baoulé Parks mean that surveilling them and providing security in adjacent communities is a daunting task. Jihadists working from these parks have displaced civilian authorities and eliminated security agents through threats and assassinations. This gap leaves local communities even more exposed to the kidnappings and extortion that jihadists regularly carry out. Moreover, it is exceedingly difficult to track insurgents in these wilderness areas during the rainy season when visibility is reduced by thick vegetation, and movement is hampered by seasonal waterways that cut across pathways. When the dry season comes, insurgents can simply melt away by crossing the border or returning to their home villages.

Nature Reserves Provide a Strategic Advantage for Insurgents

In both western Mali and northern Benin, parks and other nature reserves are strategic spaces that jihadists use to move money, guns, and hostages. Katiba Macina elements gained control of large parts of Baoulé National Park in western Mali beginning in 2019 through targeted raids on the handful of guards on the ground. In W National Park in northern Benin, insurgents demonstrated their capabilities by staging a spectacular and complex ambush in February 2022 that reportedly killed an estimated nine individuals, including five park personnel (Africanews, 11 February 2022).

The region’s protected area network is ready-made for jihadist expansion, putting their managers on the frontlines of counterinsurgency. The littoral countries of Ivory Coast, Ghana, Togo, and Benin host a total of approximately 588 underfunded protected reserves covering 142,703 square kilometers; 188 of those reserves, including four out of the five largest, are within 10 kilometers of an international border. The Ivory Coast alone is dotted with 249 reserves, none of which are more than twenty-six kilometers apart, and over a quarter of which adjoin another reserve. These protected areas are critical for preserving the region’s remaining wildlife, but they are at the core of an unprecedented security challenge. As hideouts and conduits, reserves are a tactical resource for jihadists but they are strategically useful as well since they allow armed groups to maintain a high threat to sympathy ratio amongst the civilians they target. By remaining mobile and hidden, they need to invest fewer resources in gaining legitimacy.

Jihadists operating out of Benin’s W National Park appear to be doing little to assuage local grievances, so popular support for their actions is unlikely to be broad-based. Local complicity is often limited to one or a few individuals; this likely meets jihadists’ minimum need to secure the provisions and intelligence they require to stay in the wilderness and evade government forces. Deepening popular support would likely require the kind of shadow governance that has emerged in Mali’s inland delta region (International Crisis Group, 10 December 2021). Jihadists operating in that area enforce their severe version of justice, which has significantly reduced cattle theft in the area (Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 12 July 2021). Benin’s political geography is not as amenable to this approach as the remote plains of central Mali. However, the country’s Fulani pastoralist communities are aggrieved and marginalized, which provides a potential well of support. More inclusive protected area management will play a pivotal role in determining whether jihadists can exploit popular grievances that stem in part from the coercive history of environmental conservation in the region (Ribot, 2001).

Non-governmental organizations (NGOs), such as African Parks Network, which manages several West African reserves, increasingly face the delicate challenge of protecting wildlife, accommodating local needs, and aiding governments in their growing counterinsurgency operations. Governments, their NGO partners, and other stakeholders will help keep the support of civilians living under jihadist threat only if they offer better prospects, starting with basic security and protection. Security support from Rwanda, which reportedly might include the deployment of soldiers, will play a pivotal role in this regard – if it materializes (Africa Intelligence, 9 September 2022). However, if it contributes to a lopsided response by the Beninese government that focuses on counterterrorism at the expense of civilian protection, it could make matters worse. Across the region, security forces have resorted to collective punishment of pastoralist communities out of suspicion, fear, and confusion (for more, see the ACLED report State Atrocities in the Sahel). If this occurs in Benin, the result will be tragic and counterproductive.

Update, 27 September 2022: This report has been updated to reflect the latest ACLED data for Benin.