Political Violence During Brazil’s 2022 General Elections

17 October 2022

Following the first round of voting in Brazil’s general elections on 2 October, left-wing two-time former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva – leader of the Workers’ Party (PT) and the ‘Brazil of Hope’ coalition – leads the race with 48.4% of the vote. He was followed closely by far-right incumbent President Jair Bolsonaro of the Liberal Party (PL) and the ‘For the Good of Brazil’ coalition, who outperformed the polls by receiving 43.2% of the votes. Lula’s inability to exceed 50% has forced a runoff election between Lula and Bolsonaro scheduled for 30 October. The narrow margin between the two candidates came as a surprise, as many predicted a first-round victory for Lula (BBC, 3 October 2022). The close outcome underscores the deepening polarization of Brazil’s electorate, with both contenders garnering significant popular support with opposed electoral programs.

Amid this polarization, antagonism between Bolsonaro’s administration and the opposition has fueled increased electoral violence, which continues to pose a threat ahead of the presidential runoff election. UN experts warned that threats, intimidation, and political violence “generate terror among the population and deter potential candidates from running for office,” urging Brazilian authorities to ensure the safety of candidates and most-at-risk communities (OHCHR, 22 September 2022).

Electoral Violence in Brazil

Brazil has a history of politically motivated violence around elections, with frequent targeting of political contenders and violent coercion of voters throughout the democratic period, including most recently during the 2018 general elections and the 2020 local elections. Police militias and drug trafficking groups use violence to intimidate candidates who pose a threat to their activities, as seen ahead of Brazil’s 2020 local elections (for more, see ACLED’s Municipal Candidates Under Attack in Brazil). Violence has also stemmed from acts of mob violence and armed attacks involving rival party supporters.

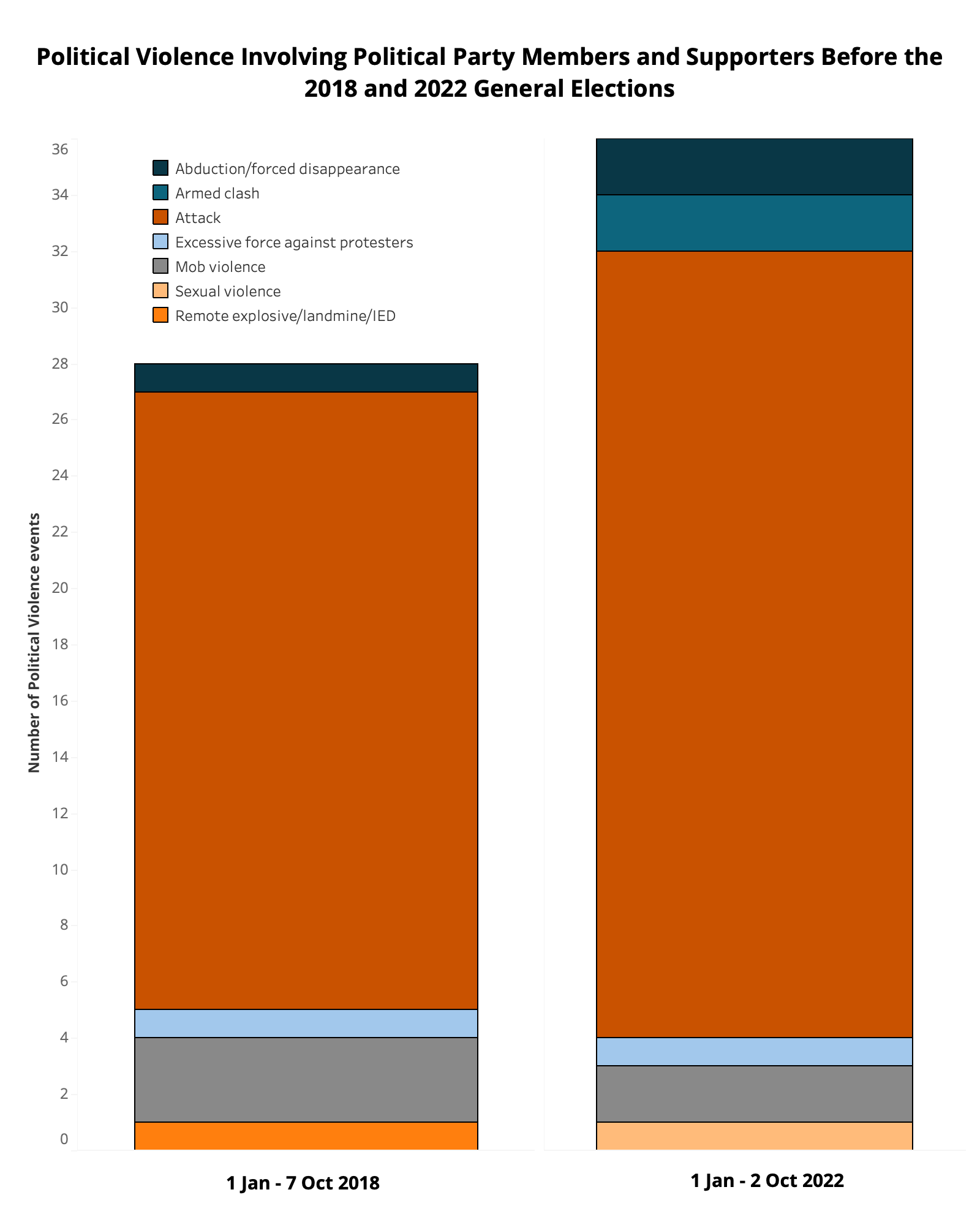

In 2018, between the start of the year and the first round of voting on 7 October, ACLED records 28 instances of political violence involving party representatives and supporters across the country (see graph below). Most notably, Bolsonaro himself was stabbed and severely injured during a campaign rally on 6 September in Juiz de Fora city, Minas Gerais state. Meanwhile, on 14 March, suspected members of a militia with alleged political ties shot and killed human rights defender and Socialism and Liberty Party (PSOL) councilwoman Marielle Franco in Rio de Janeiro city’s Central Zone.

Worryingly, the number of violent incidents involving political party representatives and supporters during the lead-up to the 2022 election eclipsed the number recorded during the 2018 election. Between the start of 2022 and the first round of voting on 2 October, ACLED records 36 instances of political violence involving party representatives and supporters across the country (see graph above). This suggests even greater tensions and polarization than recorded in the previous general elections, which may continue to trigger violence ahead of the runoff.

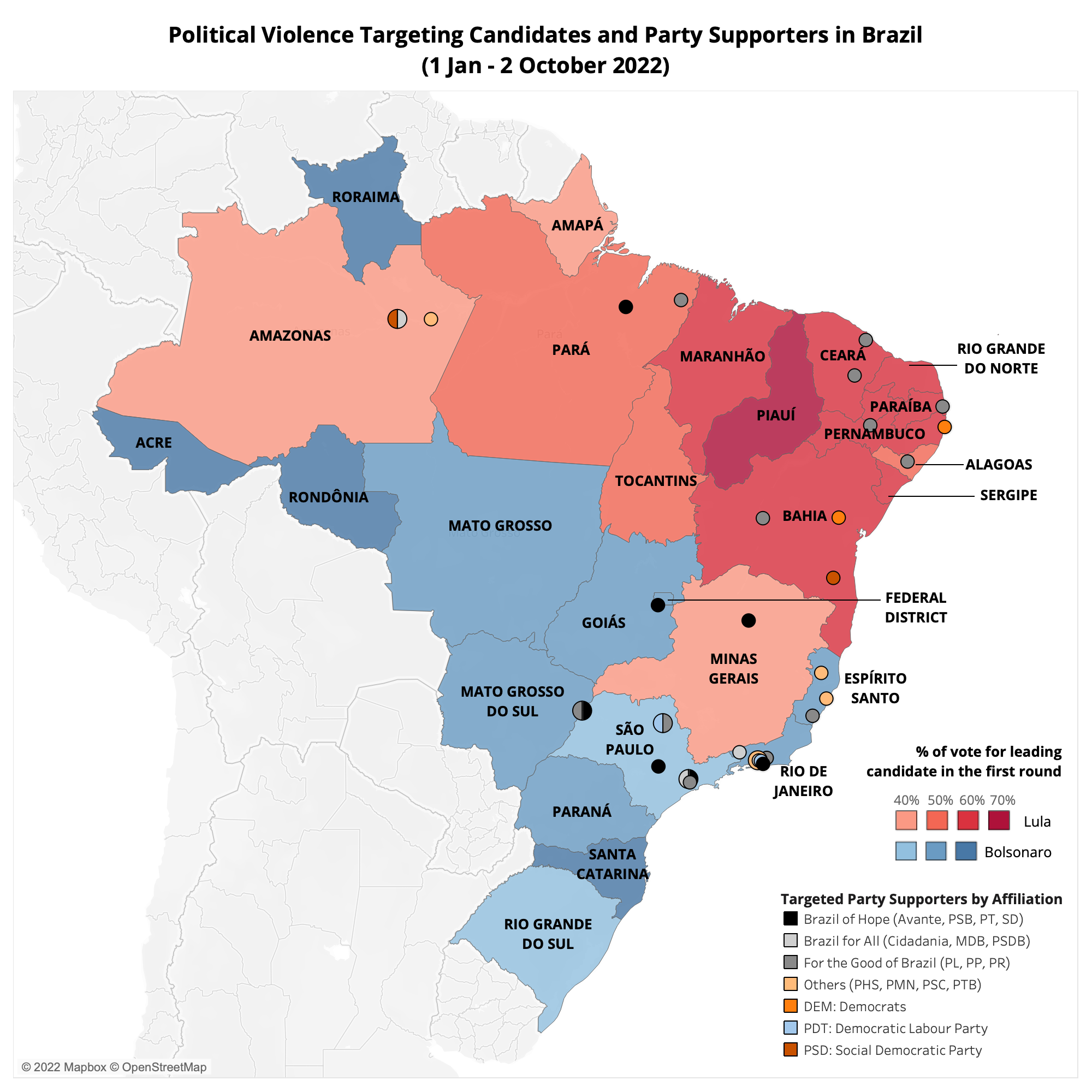

In 2022, violence has affected parties across the political spectrum, including members from constituent parties of both the ‘Brazil of Hope’ and ‘For the Good of Brazil’ coalitions, as well as the ‘Brazil for All’ coalition, which consists of center-right and catch-all parties, and other unaffiliated lists. Most instances of violence targeting party representatives and supporters have occurred in the Bolsonaro-backing states of Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, and Espírito Santo and Lula-dominant Bahia state, as well as in Amazonas state (see map below).

Voting data source: Tribunal Superior Eleitoral

As in previous electoral cycles, drug trafficking groups have been responsible for some of the violence, including shooting and injuring Brazilian Labor Party (PTB) councilman Wemerson Barriga in Itacoatiara city, Amazonas state, who has denounced drug trafficking in his community. On election day, the First Capital Command criminal organization allegedly ordered a shooting at a polling station in Sāo Paulo city’s South Zone, which injured two military police officers overseeing the election and interrupted voting for nearly an hour.

Supporters of political parties have also contributed to violence, although police have not systematically recognized the violence stemming from political disagreements between supporters as politically motivated (The Brazilian Report, 20 July 2022). Notably, PL supporters killed two PT supporters during separate attacks in the Mato Grosso and Paraná states. PL supporters were also responsible for assaulting the Democratic Labour Party (PDT) Presidential Candidate Ciro Gomes during a rally in Ribeirão Preto city, São Paulo state on 28 April. Meanwhile, a PL party leader allegedly opened fire on three of his political adversaries the night before the first round of voting in Carolina city, Maranhão state. Although ACLED data indicate that PL supporters have engaged in more direct attacks, supporters of other parties have also contributed to the overall climate of violence. On 2 October, PT and PL supporters clashed in the Rio de Janeiro city’s North Zone with sticks, stones, and smoke bombs following the results of the first round of voting, while in Recife, childhood friends stabbed each other over their political differences.

Looking Forward

With the race set to be tighter than expected, these incidents have raised concerns that political violence and clashes between PL and PT supporters will continue ahead of the runoff and even beyond the election period. Between the first and second rounds of voting in the 2018 general elections, ACLED records six incidents of violence targeting party supporters, reportedly leaving at least three people dead. Days after the announcement of the 2022 runoff, a Lula supporter stabbed and killed his Bolsonaro-supporting roommate during a political argument in Itanhaém city on the São Paulo coast. Violence might be further exacerbated as a result of Bolsonaro’s relaxed arms policies, which has led to a six-fold increase in registered gun owners during his presidency (Reuters, 21 September 2022).

Moreover, the closeness of the vote also presents further potential for violence following the runoff. Throughout his campaign, Bolsonaro has repeatedly questioned the legitimacy of the country’s voting system (Reuters, 18 July 2022; Semana, 6 October 2022), laying the groundwork to contest the final election result should he be defeated. Bolsonaro has also threatened to undermine the powers of Minister of the Supreme Court Alexandre de Moraes, also head of Brazil’s Electoral Court, who has taken preemptive measures to ensure the impartiality of the elections (G1, 7 September 2022; Forum, 9 October 2022). In addition to close relationships with the armed forces and the mostly pro-Bolsonaro military police (New York Times, 28 September 2022), Bolsonaro has demonstrated his ability to mobilize his support base. In May and September, especially during Brazil’s Independence Day celebrations on 7 September, ACLED records a spike in PL demonstration activity as supporters participated in nationwide rallies for their candidate. Notably, the former head of Brazil’s Electoral Court Judge Edson Fachin warned of the possibility of violent mobilization by PL supporters in the event of Bolsonaro’s defeat, which he described as potentially “more severe than the 6 January attack on the [United States] Capitol” (Reuters, 6 July 2022).

Despite these fears, several factors may contribute to restraining electoral violence. The Supreme Court has proactively responded to challenges to the electoral system to preemptively address potential fraud claims, adopting a zero-tolerance policy towards interference by digital militias in electronic voting (UOL, 14 June 2022). It also ordered raids on the homes of Bolsonaro-supporting businessmen following accusations that they supported a coup d’état over Lula’s return to the presidency (Reuters, 3 August 2022), underscoring the importance of Brazil’s independent institutions to safeguarding democracy. Meanwhile, incidents at polling stations and demonstrations challenging the results of the first round of voting have remained scarce and, on the campaign trail, Bolsonaro rallies and protests have so far been predominantly nonviolent. These trends will be imperative to monitor going into the runoff and beyond.

Visuals in this report were produced by Ana Marco