Political Violence During Brazil’s 2022 Presidential Runoff

7 December 2022

Following his victory in the presidential runoff election on 30 October, President-elect Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva described Brazil as “one country, one people, one great nation.” While this speech may indicate the incoming president’s willingness to seek unity, it comes at a time of heightened political polarization in Brazil. Inflammatory rhetoric around the elections and spikes in political violence throughout the election period have raised concerns over the potential for further outbreaks of unrest, even beyond the aftermath of the runoff. The contestation of the election results and calls for military intervention by supporters of outgoing President Jair Bolsonaro present an ongoing challenge to the “peace and unity” promoted by President-elect Lula in his victory speech (Folha de S.Paulo, 31 October 2022).

Electoral Violence and Voter Intimidation Before and During the Runoff

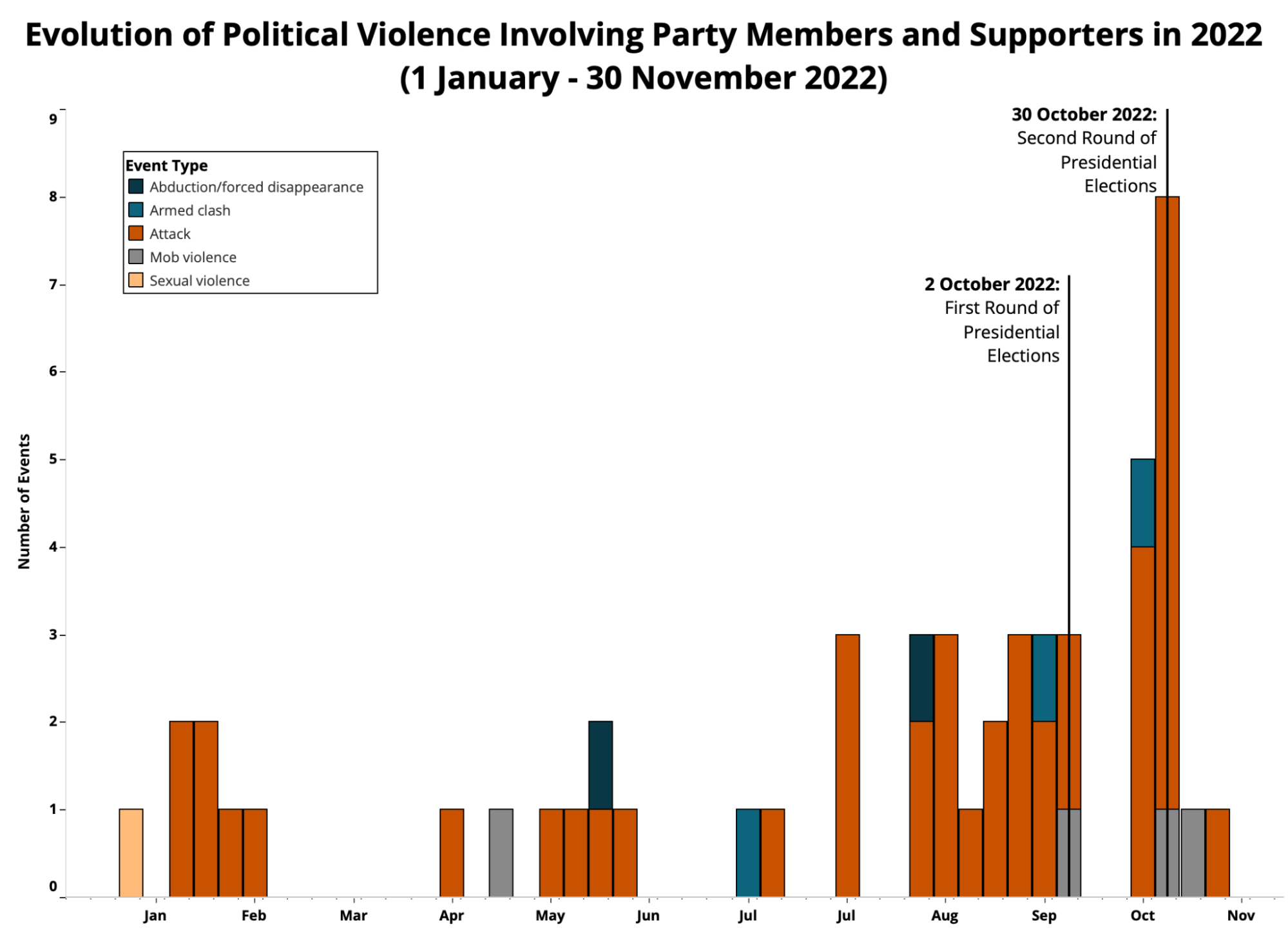

The lead-up to the first round of voting on 2 October saw higher levels of political violence involving political party representatives and supporters than the 2018 election (for more on electoral violence in Brazil, see ACLED’s Election Watch report on the first round of voting). These heightened levels continued in the lead-up to the runoff, with violence further surging on voting day (see graph below). Between 3 and 30 October, ACLED records 13 political violence events involving party representatives and supporters, which led to six reported fatalities, a figure twice as high as during the same period in 2018.

Runoff election violence primarily consisted of direct armed attacks, which largely targeted members and supporters of Lula’s Workers’ Party (PT). There were at least seven violent incidents targeting PT supporters during this period, six of which occurred on voting day. The use of direct attacks contrasts with the 2018 elections, which mainly saw clashes between pro-Bolsonaro and pro-PT supporters during the runoff. Violence during this year’s runoff occurred mostly in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo states, where Bolsonaro led in the vote count. At the national level, the incidence of political violence in states won by Lula was half that recorded in states won by Bolsonaro.

While the perpetrators of election-related violence were not systematically identified, ACLED records the participation of state forces in at least three events. Notably, on election day, six military officers beat a man with a stick and used pepper spray on Lula supporters celebrating election results in a bar in Anápolis. Through a range of different policies favoring the armed forces, Bolsonaro has courted members of the military police. In return, some have shown their support to the Liberal Party (PL) candidate, including on social network platforms (Forum Segurança, 2 September 2021). Similar to the violence preceding the first round of voting, PL supporters engaged in armed attacks on civilians, reportedly killing at least three people. Notably, in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais state, a PL supporter opened fire at a party celebrating Lula’s victory, reportedly killing two people, including a 12-year-old Black girl, and injuring four others.

In addition to physical violence, the runoff was also marked by other forms of coercion ahead of voting. On election day, the director of the Federal Highway Police defied a Supreme Electoral Court ruling and ordered officers to carry out operations, leading to the stalling of buses carrying voters in the pro-Lula northeast and other key PT areas of support (Washington Post, 30 October 2022). In Tocantins and Pará states, local businesses, mayors, and ranchers allegedly threatened members of Indigenous groups and offered benefits in exchange for abstention or a vote in favor of Bolsonaro (Brasil de Fato, 29 October 2022). Meanwhile, in Paraná state, an agribusiness company pressured its employees to vote for Bolsonaro (Brasil de Fato, 25 October 2022).

Organized crime groups were also reported to have directed votes in areas under gang control (Globo Extra, 9 September 2022; Informe Agora, 19 November 2022). In the North zone of Rio de Janeiro, the Public Prosecutor’s Office requested protection for voters following reports that drug traffickers were pressuring residents to vote for a specific candidate (Brasil de Fato, 25 October 2022). In Rio das Ostras, members of the Red Command coerced voters and circulated warnings against voting for Bolsonaro (Crimes News RJ, 11 October 2022).

Violence and Unrest After the Elections

Election-related violence and unrest continued well after the results were announced. Following Lula’s narrow victory, PL supporters set up roadblocks across the country to contest the election result and call for military intervention. Demonstrations began on 30 October and culminated on 1 November, with more than 520 events recorded that day, fueled by Bolsonaro’s failure to immediately recognize his opponent’s victory and his previous criticisms of the integrity of Brazil’s voting system.

While the majority of pro-Bolsonaro demonstrations remained peaceful, violent demonstrations accounted for about 11% of events between 30 October and 30 November. In contrast, anti-Bolsonaro mobilization before and after the 2018 presidential runoff did not lead to notable outbreaks of violence, and protests were met with limited state intervention. Demonstrators set fire to barricades and engaged with state forces attempting to disperse roadblocks in over 20 instances. The roadblocks exacerbated tensions between Bolsonaro supporters and passersby. Demonstrators used violence against civilians during at least 10 events, including drivers trying to pass through roadblocks. There were also reports of violence directed at pro-Bolsonaro demonstrators, with opponents opening fire near roadblocks, trying to drive over barricades, and engaging in physical fights in at least six events.

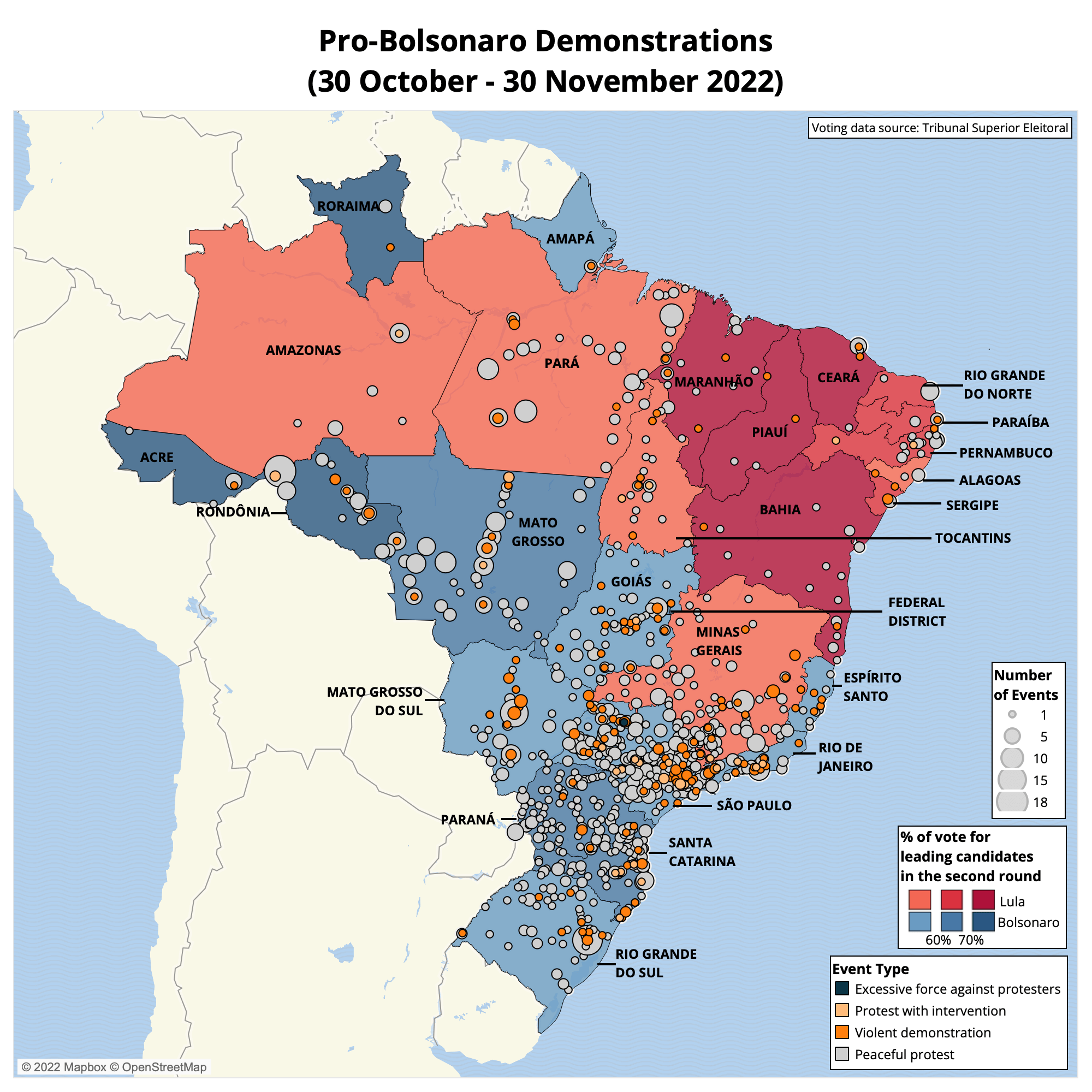

ACLED data show that between 30 October and 30 November, the highest number of demonstration events organized by PL supporters took place in states where Bolsonaro won the popular vote, such as São Paulo, Paraná, Mato Grosso, Santa Catarina, Rio Grande do Sul, Mato Grosso do Sul, Goiás, and Rondônia. High levels of demonstration activity were also reported in Minas Gerais and Pará states, where Bolsonaro received a large number of votes, despite losing to Lula. Similarly, over half of all violent pro-Bolsonaro demonstrations were reported in São Paulo, Mato Grosso do Sul, Minas Gerais, and Goiás states (see map below).

In the weeks following the runoff, violence targeting party members and supporters decreased. Instead, other forms of violence have emerged, including targeted destruction of property. Since 30 October, ACLED has recorded multiple incidents of targeted property destruction, including shootings directed at the PT headquarters and party supporters’ houses, vandalism to water pipes, and arson. Far-right groups have also spread boycott lists of pro-Lula businesses in Rondônia and São Paulo, allegedly leading to a shooting at a pizzeria in Ji-Paraná, Rondônia (G1, 4 November 2022). Journalists have also been the victims of targeted attacks since the runoff. On 2 November, Bolsonaro supporters attacked and destroyed the equipment of journalists covering demonstrations against the election result in Porto Alegre in Rio Grande do Sul and Cuiabá in Mato Grosso. Another journalist was beaten in Itajai, Santa Caterina, for uploading videos of Bolsonaro supporters on social media. Meanwhile, in Porto Velho, Rondônia, armed men opened fire at the headquarters of the Rondoniaovivo newspaper. The newspaper was allegedly targeted because of its critical coverage of pro-Bolsonaro demonstrations (Committee to Protect Journalists, 17 November 2022).

Even in the context of Brazil’s history of election-related violence, the 2022 presidential elections saw heightened levels of political violence. In the lead-up to the first round and the runoff, the targeting of political party representatives and supporters surpassed that of the 2018 election. While drug trafficking groups were responsible for a number of violent events, violence perpetrated by supporters of political parties has increased, especially among Bolsonaro’s support base. Moreover, in 2022, new disorder trends have emerged, including a spike in pro-Bolsonaro demonstrations contesting the election results and non-direct attacks targeting the property of rival party supporters.

Despite measures to address weaknesses in Brazil’s voting system, as well as the endorsement of the results by international bodies and Brazilian institutions, including the Ministry of Defense, ACLED has continued to record demonstrations, sometimes violent, contesting the election nearly a month later. Ongoing moves by state institutions to reinforce the validity of the election results continue to be rejected by a large number of Bolsonaro supporters. Starting on 15 November, pro-Bolsonaro demonstrators set up additional roadblocks, triggered by a Supreme Federal Court order to freeze the bank accounts of alleged organizers of the mobilization (Gazeta do Povo, 18 November 2022). The ruling out of Bolsonaro’s request to annul votes from several electronic voting machines and the decision to issue a fine against the PL for filing the complaint “in bad faith” also sparked outrage among Bolsonaro’s supporters (Brasil de Fato, 23 November 2022; Congresso em Foco, 23 November 2022). The ongoing unrest and stark polarization thus raise difficult prospects for the reconciliation of the Brazilian electorate as President-elect Lula approaches the start of his mandate in January 2023.

Visuals in this report were produced by Ana Marco